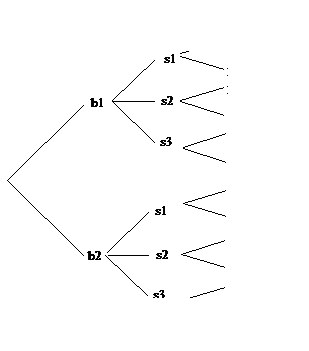

Let us suppose that the row player uses the strategy

. Now if the column player plays column 1, the expected payoff

P for the row player is

. Now if the column player plays column 1, the expected payoff

P for the row player is

P(r)=1(r)+(−3)(1−r)=4r−3.

Which can also be computed as follows:

or

4r−3.

or

4r−3.

If the row player plays the strategy

and the column player plays column 2, the expected payoff

P for the row player is

and the column player plays column 2, the expected payoff

P for the row player is

.

.

We have two equations

P(r)=4r−3 and

P(r)=−6r+4

The row player is trying to improve upon his worst scenario, and that only happens when the two lines intersect. Any point other than the point of intersection will not result in optimal strategy as one of the expectations will fall short.

Solving for

r algebraically, we get

(19.3)4r−3=−6r+4

r=7/10.

Therefore, the optimal strategy for the row player is

.

.

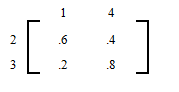

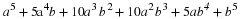

Alternatively, we can find the optimal strategy for the row player by, first, multiplying the row matrix with the game matrix as shown below.

And then by equating the two entries in the product matrix. Again, we get

r=.7, which gives us the optimal strategy

.

.

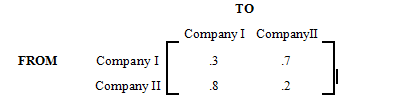

We use the same technique to find the optimal strategy for the column player.

Suppose the column player's optimal strategy is represented by

. We, first, multiply the game matrix by the column matrix as shown below.

. We, first, multiply the game matrix by the column matrix as shown below.

And then equate the entries in the product matrix. We get

(19.6)3c−2=−7c+4

(19.7)c=.6

Therefore, the column player's optimal strategy is

.

.

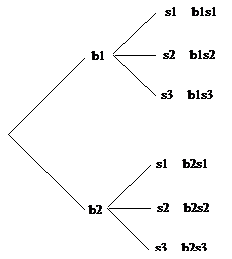

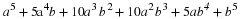

To find the expected value,

V, of the game, we find the product of the matrices

R,

G and

C.

That is, if both players play their optimal strategies, the row player can expect to lose

.2 units for every game.