Should you ever find yourself stuck with a mathematics question on a television quiz show, you will probably wish you had remembered how many even prime numbers there are between 1 and 100 for the sake of R1 000 000. And who does not want to be a millionaire, right?

Welcome to the Grade 10 Finance Chapter, where we apply maths skills to everyday financial situations that you are likely to face both now and along your journey to purchasing your first private jet.

If you master the techniques in this chapter, you will grasp the concept of compound interest, and how it can ruin your fortunes if you have credit card debt, or make you millions if you successfully invest your hard-earned money. You will also understand the effects of fluctuating exchange rates, and its impact on your spending power during your overseas holidays!

Before we begin discussing exchange rates it is worth noting that the vast majority of countries use a decimal currency system. This simply means that countries use a currency system that works with powers of ten, for example in South Africa we have 100 (10 squared) cents in a rand. In America there are 100 cents in a dollar. Another way of saying this is that the country has one basic unit of currency and a sub-unit which is a power of 10 of the major unit. This means that, if we ignore the effect of exchange rates, we can essentially substitute rands for dollars or rands for pounds.

Is $500 ("500 US dollars") per person per night a good deal on a hotel in New York City? The first question you will ask is “How much is that worth in Rands?". A quick call to the local bank or a search on the Internet (for example on http://www.x-rates.com/) for the Dollar/Rand exchange rate will give you a basis for assessing the price.

A foreign exchange rate is nothing more than the price of one currency in terms of another. For example, the exchange rate of 6,18 Rands/US Dollars means that $1 costs R6,18. In other words, if you have $1 you could sell it for R6,18 - or if you wanted $1 you would have to pay R6,18 for it.

But what drives exchange rates, and what causes exchange rates to change? And how does this affect you anyway? This section looks at answering these questions.

How much is R1 really worth?

We can quote the price of a currency in terms of any other currency, for example, we can quote the Japanese Yen in term of the Indian Rupee. The US Dollar (USD), British Pound Sterling (GBP) and the Euro (EUR) are, however, the most common used market standards. You will notice that the financial news will report the South African Rand exchange rate in terms of these three major currencies.

Table 2.1. Abbreviations and symbols for some common currencies.|

Currency

|

Abbreviation

|

Symbol

|

| South African Rand | ZAR | R |

| United States Dollar | USD | $ |

| British Pounds Sterling | GBP | £ |

So the South African Rand, noted ZAR, could be quoted on a certain date as 6,07040 ZAR per USD (i.e. $1,00 costs R6,07040), or 12,2374 ZAR per GBP. So if I wanted to spend $1 000 on a holiday in the United States of America, this would cost me R6 070,40; and if I wanted £1 000 for a weekend in London it would cost me R12 237,40.

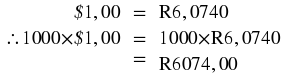

This seems obvious, but let us see how we calculated those numbers:

The rate is given as ZAR per USD, or ZAR/USD such that $1,00 buys R6,0704. Therefore, we need to multiply by 1 000 to get the number of Rands per $1 000.

Mathematically,

as expected.

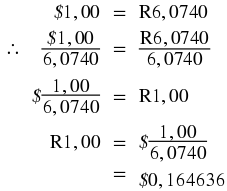

What if you have saved R10 000 for spending money for the same trip and you wanted to use this to buy USD? How many USD could you get for this? Our rate is in ZAR/USD but we want to know how many USD we can get for our ZAR. This is easy. We know how much $1,00 costs in terms of Rands.

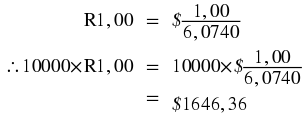

As we can see, the final answer is simply the reciprocal of the ZAR/USD rate. Therefore, for R10 000 will get:

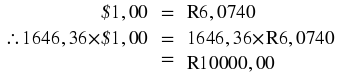

We can check the answer as follows:

Six of one and half a dozen of the other

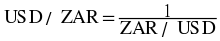

So we have two different ways of expressing the same exchange rate: Rands per Dollar (ZAR/USD) and Dollar per Rands (USD/ZAR). Both exchange rates mean the same thing and express the value of one currency in terms of another. You can easily work out one from the other - they are just the reciprocals of the other.

If the South African Rand is our domestic (or home) currency, we call the ZAR/USD rate a “direct" rate, and we call a USD/ZAR rate an “indirect" rate.

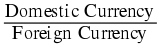

In general, a direct rate is an exchange rate that is expressed as units of home currency per units of foreign currency, i.e.,  .

.

The Rand exchange rates that we see on the news are usually expressed as direct rates, for example you might see:

Table 2.2. Examples of exchange rates|

Currency Abbreviation

|

Exchange Rates

|

| 1 USD | R6,9556 |

| 1 GBP | R13,6628 |

| 1 EUR | R9,1954 |

The exchange rate is just the price of each of the Foreign Currencies (USD, GBP and EUR) in terms of our domestic currency, Rands.

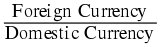

An indirect rate is an exchange rate expressed as units of foreign currency per units of home currency, i.e.  .

.

Defining exchange rates as direct or indirect depends on which currency is defined as the domestic currency. The domestic currency for an American investor would be USD which is the South African investor's foreign currency. So direct rates, from the perspective of the American investor (USD/ZAR), would be the same as the indirect rate from the perspective of the South Africa investor.

Since exchange rates are simply prices of currencies, movements in exchange rates means that the price or value of the currency has changed. The price of petrol changes all the time, so does the price of gold, and currency prices also move up and down all the time.

If the Rand exchange rate moved from say R6,71 per USD to R6,50 per USD, what does this mean? Well, it means that $1 would now cost only R6,50 instead of R6,71. The Dollar is now cheaper to buy, and we say that the Dollar has depreciated (or weakened) against the Rand. Alternatively we could say that the Rand has appreciated (or strengthened) against the Dollar.

What if we were looking at indirect exchange rates, and the exchange rate moved from $0,149 per ZAR (= ) to $0,1538 per ZAR (=

) to $0,1538 per ZAR (= ).

).

Well now we can see that the R1,00 cost $0,149 at the start, and then cost $0,1538 at the end. The Rand has become more expensive (in terms of Dollars), and again we can say that the Rand has appreciated.

Regardless of which exchange rate is used, we still come to the same conclusions.

In general,

for direct exchange rates, the home currency will appreciate (depreciate) if the exchange rate falls (rises)

For indirect exchange rates, the home currency will appreciate (depreciate) if the exchange rate rises (falls)

As with just about everything in this chapter, do not get caught up in memorising these formulae - doing so is only going to get confusing. Think about what you have and what you want - and it should be quite clear how to get the correct answer.

Discussion : Foreign Exchange Rates

In groups of 5, discuss:

Why might we need to know exchange rates?

What happens if one country's currency falls drastically vs another country's currency?

When might you use exchange rates?

Cross Currency Exchange Rates

We know that exchange rates are the value of one currency expressed in terms of another currency, and we can quote exchange rates against any other currency. The Rand exchange rates we see on the news are usually expressed against the major currencies, USD, GBP and EUR.

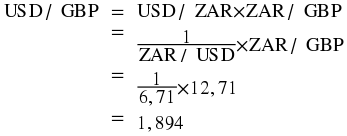

So if for example, the Rand exchange rates were given as 6,71 ZAR/USD and 12,71 ZAR/GBP, does this tell us anything about the exchange rate between USD and GBP?

Well I know that if $1 will buy me R6,71, and if £1.00 will buy me R12,71, then surely the GBP is stronger than the USD because you will get more Rands for one unit of the currency, and we can work out the USD/GBP exchange rate as follows:

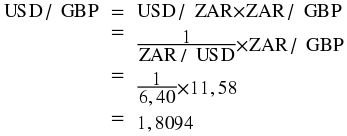

Before we plug in any numbers, how can we get a USD/GBP exchange rate from the ZAR/USD and ZAR/GBP exchange rates?

Well,

(2.5)

USD

/

GBP

=

USD

/

ZAR

×

ZAR

/

GBP

.

Note that the ZAR in the numerator will cancel out with the ZAR in the denominator, and we are left with the USD/GBP exchange rate.

Although we do not have the USD/ZAR exchange rate, we know that this is just the reciprocal of the ZAR/USD exchange rate.

Now plugging in the numbers, we get:

Note

Sometimes you will see exchange rates in the real world that do not appear

to work exactly like this. This is usually because some financial institutions

add other costs to the exchange rates, which alter the results. However, if you

could remove the effect of those extra costs, the numbers would balance again.

Exercise 2.1.1. Cross Exchange Rates (Go to Solution)

If $1 = R 6,40, and £1 = R11,58 what is the $/£ exchange rate (i.e. the number of US$ per £)?

Investigation : Cross Exchange Rates - Alternative Method

If $1 = R

6,40, and £1 = R11,58 what is the $/£ exchange rate (i.e. the

number of US$ per £)?

Overview of problem

You need the $/£ exchange rate, in other words how many dollars must you pay for a pound. So you need £1. From the given information we know that it would cost you R11,58 to buy £1 and that $ 1 = R6,40.

Use this information to:

calculate how much R1 is worth in $.

calculate how much R11,58 is worth in $.

Do you get the same answer as in the worked example?

Enrichment: Fluctuating exchange rates

If everyone wants to buy houses in a certain suburb, then house prices are going to go up - because the buyers will be competing to buy those houses. If there is a suburb where all residents want to move out, then there are lots of sellers and this will cause house prices in the area to fall - because the buyers would not have to struggle as much to find an eager seller.

This is all about supply and demand, which is a very important section in the study of Economics. You can think about this is many different contexts, like stamp-collecting for example. If there is a stamp that lots of people want (high demand) and few people own (low supply) then that stamp is going to be expensive.

And if you are starting to wonder why this is relevant - think about currencies. If you are going to visit London, then you have Rands but you need to “buy" Pounds. The exchange rate is the price you have to pay to buy those Pounds.

Think about a time where lots of South Africans are visiting the United Kingdom, and other South Africans are importing goods from the United Kingdom. That means there are lots of Rands (high supply) trying to buy Pounds. Pounds will start to become more expensive (compare this to the house price example at the start of this section if you are not convinced), and the exchange rate will change. In other words, for R1 000 you will get fewer Pounds than you would have before the exchange rate moved.

Another context which might be useful for you to understand this: consider what would happen if people in other countries felt that South Africa was becoming a great place to live, and that more people were wanting to invest in South Africa - whether in properties, businesses - or just buying more goods from South Africa. There would be a greater demand for Rands - and the “price of the Rand" would go up. In other words, people would need to use more Dollars, or Pounds, or Euros ... to buy the same amount of Rands. This is seen as a movement in exchange rates.

Although it really does come down to supply and demand, it is interesting to think about what factors might affect the supply (people wanting to “sell" a particular currency) and the demand (people trying to “buy" another currency). This is covered in detail in the study of Economics, but let us look at some of the basic issues here.

There are various factors which affect exchange rates, some of which have more economic rationale than others:

economic factors (such as inflation figures, interest rates, trade deficit information, monetary policy and fiscal policy)

political factors (such as uncertain political environment, or political unrest)

market sentiments and market behaviour (for example if foreign exchange markets perceived a currency to be overvalued and starting selling the currency, this would cause the currency to fall in value - a self-fulfilling expectation).

I want to buy an IPOD that costs £100, with the exchange rate currently at

£1 = R14. I believe the exchange rate will reach

R12 in a month.

How much will the MP3 player cost in Rands, if I buy it now?

How much will I save if the exchange rate drops to

R12?

How much will I lose if the exchange rate moves to

R15?

Click here for the solution

Study the following exchange rate table:

Table 2.3. | Country | Currency | Exchange Rate |

| United Kingdom (UK) | Pounds(£) |

|

| United States (USA) | Dollars ($) |

|

In South Africa the cost of a new Honda Civic is  . In England the same vehicle costs

. In England the same vehicle costs  and in the USA $

and in the USA $  . In which country is the car the cheapest when you compare the prices converted to South African Rand ?

. In which country is the car the cheapest when you compare the prices converted to South African Rand ?

Sollie and Arinda are waiters in a South African restaurant attracting many tourists from abroad. Sollie gets a

£6 tip from a tourist and Arinda gets $ 12.

How many South African Rand did each one get ?

Click here for the solution