PART

2

B

Wha r

t H ain

appens

to the

in AD

The

Hallmarks of AD

Alzheimer’s disease disrupts critical metabolic AMYLOID PLAQUES

processes that keep neurons healthy. These Amyloid plaques are found in the spaces between disruptions cause nerve cells in the brain the brain’s nerve cells. They were first described to stop working, lose connections with by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1906. Plaques consist other nerve cells, and finally die. The destruction

of largely insoluble deposits of an apparently toxic

and death of nerve cells causes the memory failure, protein peptide, or fragment, called beta-amyloid.

personality changes, problems in carrying out

We now know that some people develop

daily activities, and other features of the disease.

some plaques in their brain tissue as they age.

The brains of people with AD have an abundance However, the AD brain has many more plaques of two abnormal structures—amyloid plaques

in particular brain regions. We still do not know

and neurofibrillary tangles—that are made of

whether amyloid plaques themselves cause AD or

misfolded proteins (see Protein Misfolding on

whether they are a by-product of the AD process.

page 41 for more information). This is especially

We do know that genetic mutations can increase

true in certain regions of the brain that are

production of beta-amyloid and can cause rare,

important in memory.

inherited forms of AD (see Genes and Early-

The third main feature of AD is the loss of

Onset Alzheimer’s Disease on page 38 for

connections between cells. This leads to dimin-

more on inherited AD).

ished cell function and cell death.

To view a video showing what happens to

the brain in AD, go to www.nia.nih.gov/

alzheimers/alzheimers-disease-video.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery 21

P A R T 2 What Happens to the Brain in AD

From APP to Beta-Amyloid Plaques

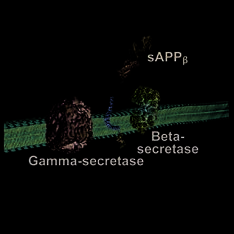

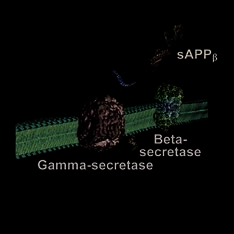

the APP molecule at one

end of the beta-amyloid

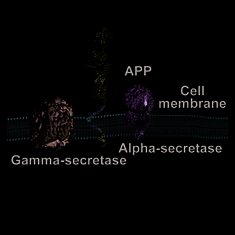

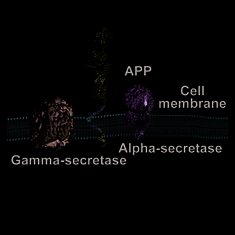

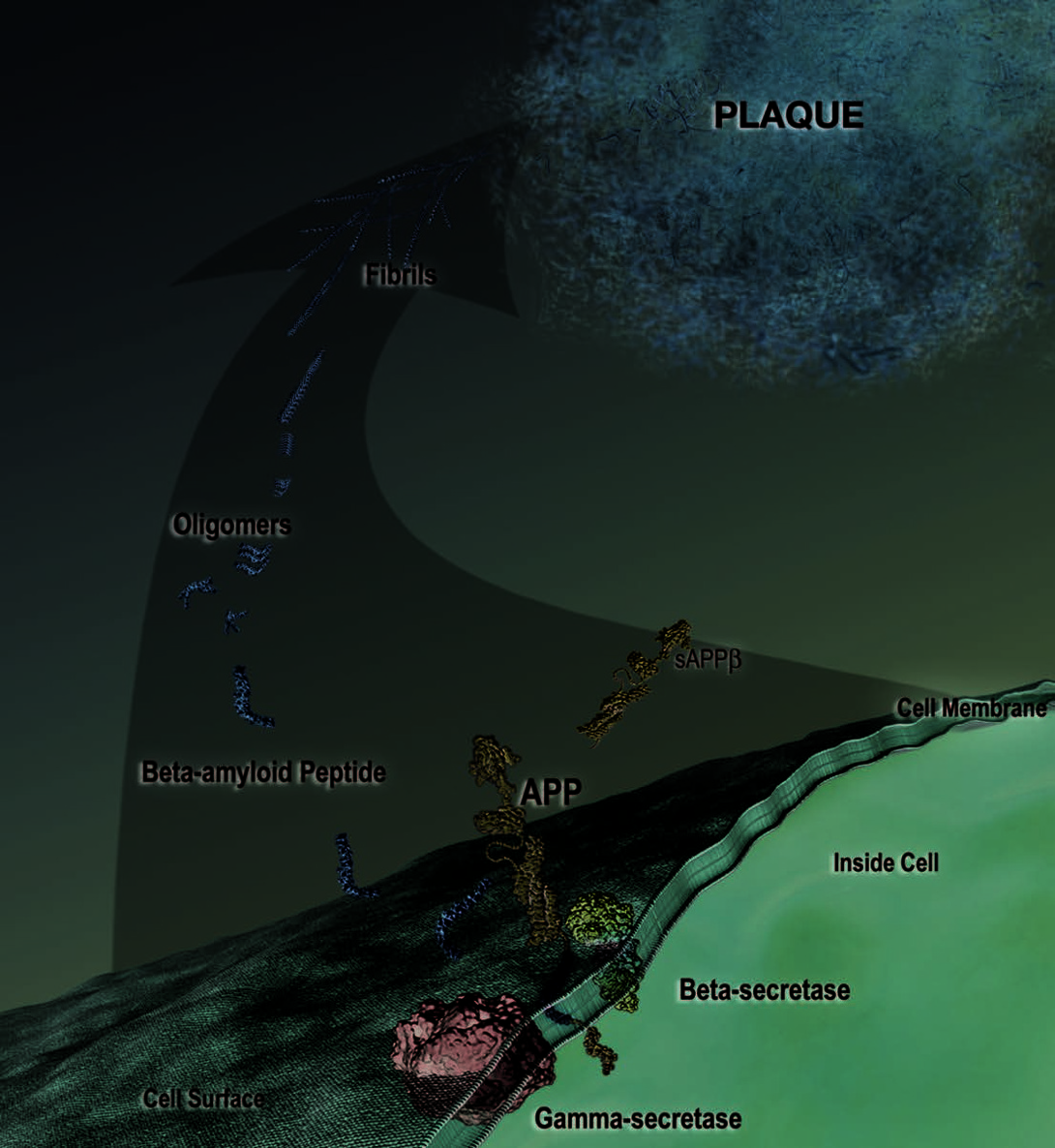

Amyloid precursor protein (APP), the starting

point for amyloid plaques, is one of many proteins

associated with the cell membrane, the barrier that

peptide, releasing sAPPβ

encloses the cell. As it is being made inside the cell,

from the cell (Figure 3).

APP becomes embedded in the membrane, like a tooth-

Gamma-secretase then

pick stuck through the skin of an orange (Figure 1).

cuts the resulting APP

In a number of cell com-

fragment, still tethered in

Figure 3

partments, including the

the neuron’s membrane,

outermost cell membrane,

at the other end of the

specific enzymes snip, or

beta-amyloid pep tide.

cleave, APP into discrete

Following the cleavages

fragments. In 1999 and

at each end, the beta-

2000, scientists identified

amyloid peptide is

Figure 1

the enzymes responsible for

released into the space

cleaving APP. These enzymes are called alpha-

outside the neuron and

Figure 4

secretase, beta-secretase, and gamma-secretase.

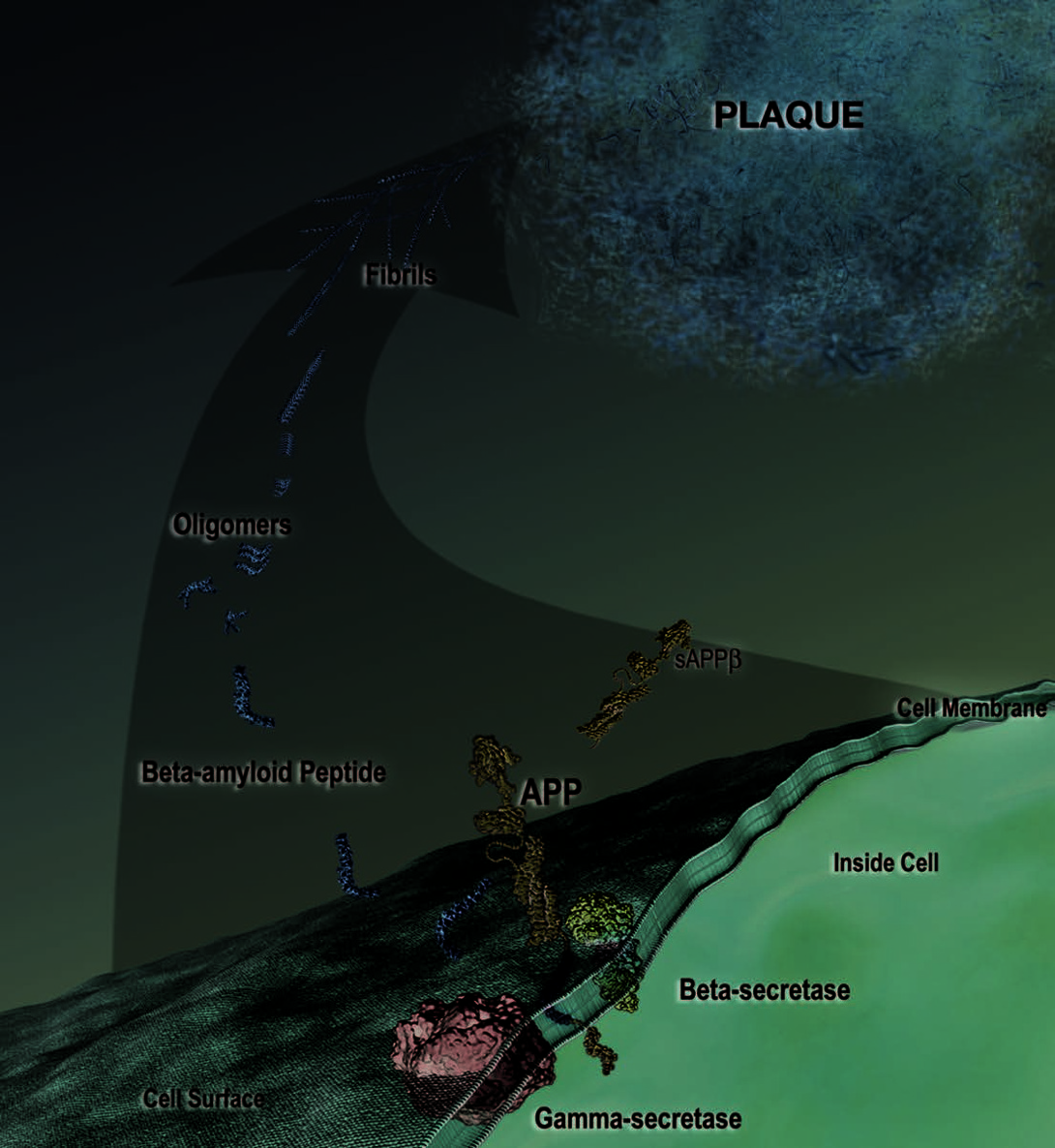

begins to stick to other

In a major breakthrough, scientists then discov ered

beta-amyloid peptides (Figure 4). These small,

that, depending on which enzyme is involved and

soluble aggregates of two, three, four, or even

the segment of APP where the cleaving occurs, APP

up to a dozen beta-amyloid peptides are called

processing can follow one of two pathways that

oligomers. Specific sizes of oligomers may

have very different consequences for the cell.

be responsible for reacting with receptors on

In the benign pathway, alpha-secretase cleaves the

neighboring cells and synapses, affecting their

APP molecule within the portion that has the potential to ability to function.

become beta-amyloid. This eliminates the production of

It is likely that some oligomers are cleared from

the beta-amyloid peptide and the potential for plaque

the brain. Those that cannot be cleared clump

buildup. The cleavage releases from the neuron a frag-

together with more beta-amyloid peptides. As the

ment called sAPPα, which has beneficial prop erties,

process continues, oligomers grow larger, becoming

such as promoting neuronal growth and survival. The

entities called protofibrils and fibrils. Eventually, other remaining APP fragment, still tethered in the neuron’s

proteins and cellular material are added, and these

membrane, is then cleaved by gamma-secretase at

increasingly insoluble entities combine to become the

the end of the beta-amyloid segment. The smaller of

well-known plaques that are characteristic of AD.

the resulting fragments also is released into the space

For many years, scientists thought that plaques

outside the neuron, while

might cause all of the damage to neurons that is seen

the larger fragment remains

in AD. However, that concept has evolved greatly

within the neuron and

in the past few years. Many scientists now think that

interacts with factors in the

oligomers may be a major culprit. Many scientists

nucleus (Figure 2).

also think that plaques actually may be a late-stage

In the harmful pathway, attempt by the brain to get this harmful beta-amyloid beta-secretase first cleaves away from neurons.

Figure 2

22 ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery

From APP to Beta-Amyloid Plaque

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery 23

P A R T 2 What Happens to the Brain in AD

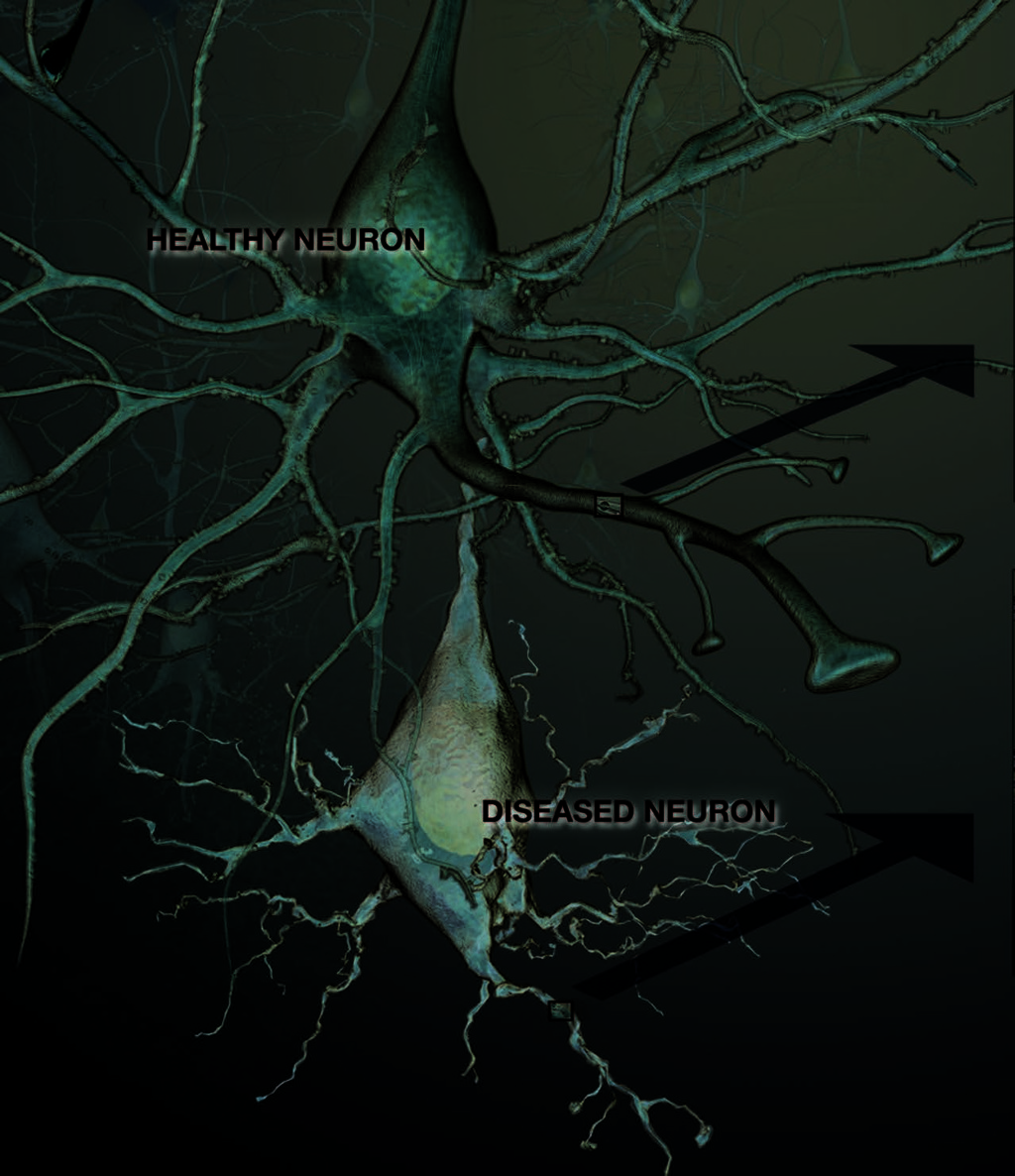

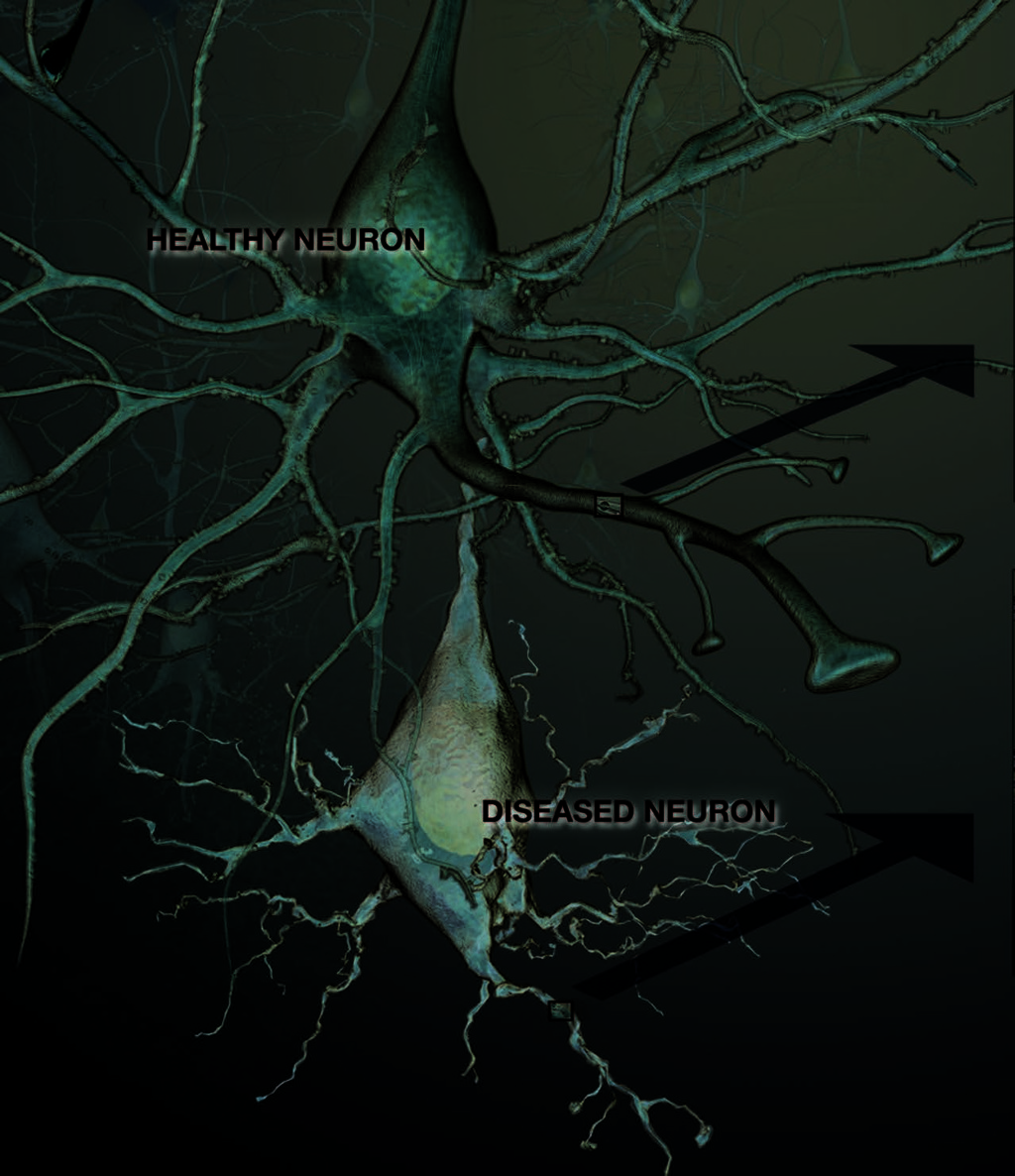

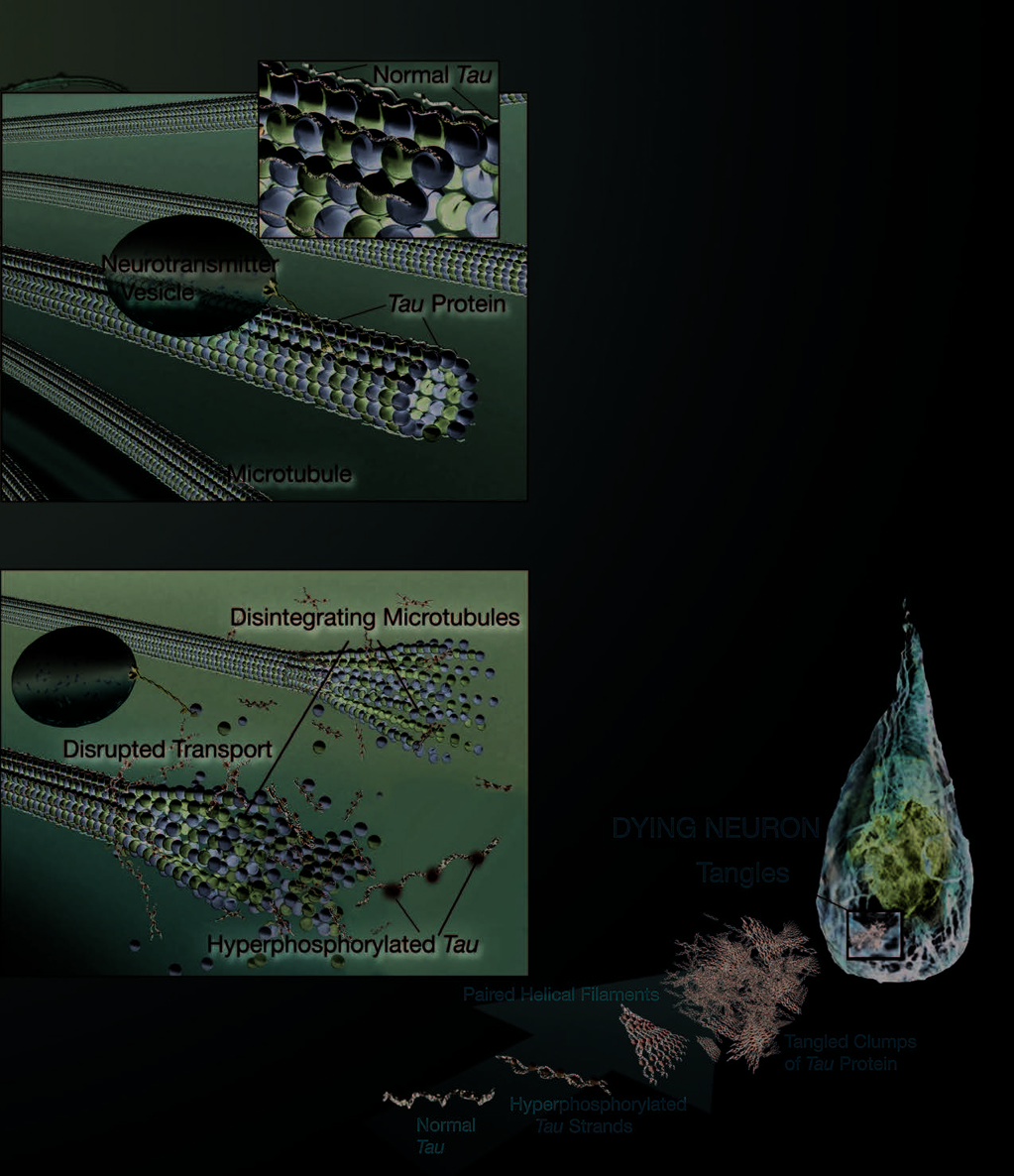

Healthy and Diseased Neurons

24

24 ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery

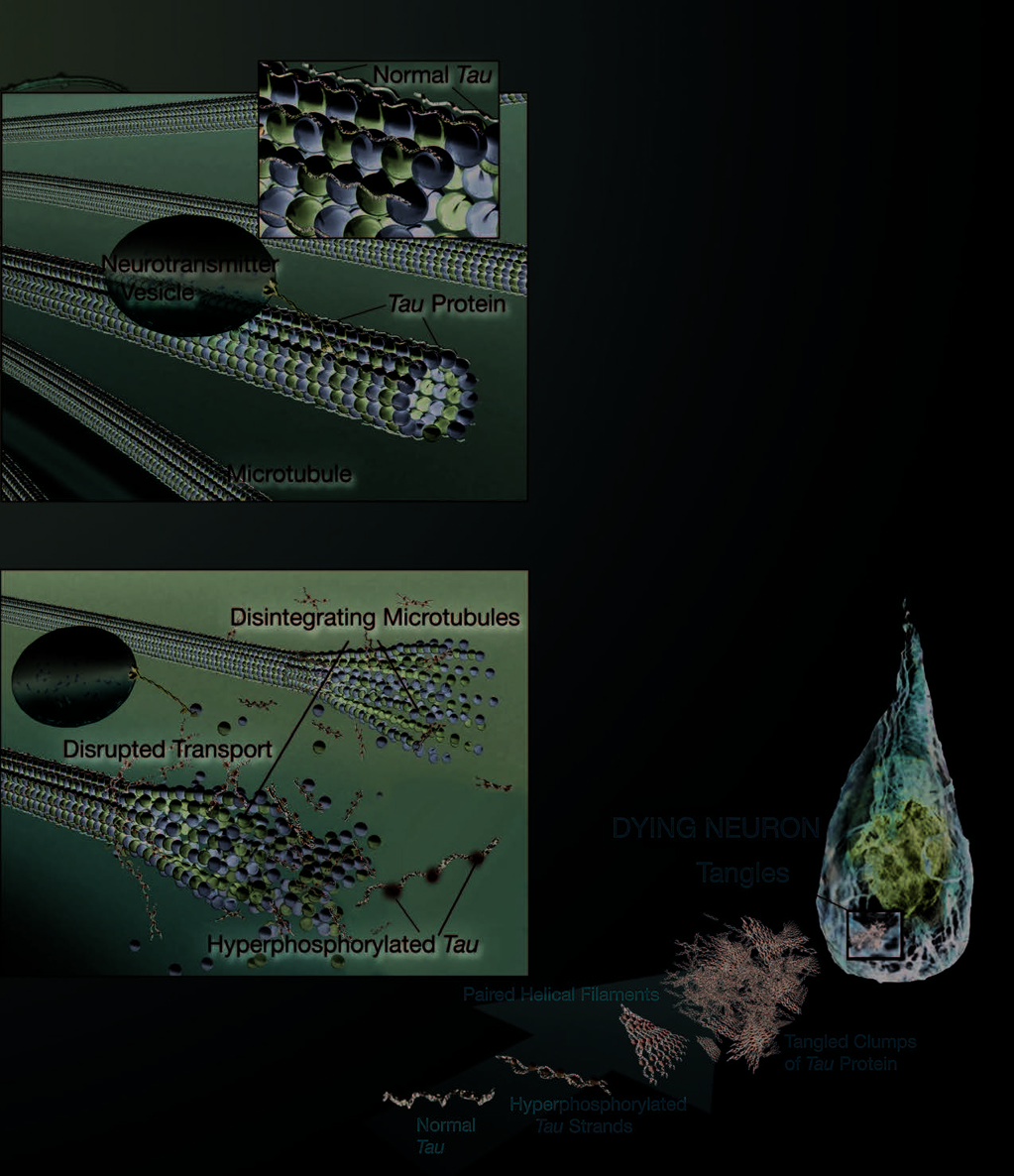

Inside a

NEUROFIBRILLARY TANGLES

Healthy Neuron

The second hallmark of AD, also described by

Dr. Alzheimer, is neurofibrillary tangles. Tangles

are abnormal collections of twisted protein

threads found inside nerve cells. The chief

component of tangles is a protein called tau.

Healthy neurons are internally supported

in part by structures called microtubules,

which help transport nutrients and other

cellular components, such as neurotransmitter-

containing vesicles, from the cell body

down the axon.

Tau, which usually has a certain number of

phosphate molecules attached to it, binds to

microtubules and appears to stabilize them. In

AD, an abnormally large number of additional

phosphate molecules attach to tau. As a result

of this “hyperphosphorylation,” tau disengages

from the microtubules and begins to come

together with other tau threads. These tau

Inside a Diseased Neuron

threads form structures called paired helical

filaments, which can become enmeshed

with one another, forming tangles

within the cell. The microtubules can

disintegrate in the process, collaps-

ing the neuron’s internal transport

network. This collapse damages

the ability of neurons to com-

municate with each other.

Formation of Tau Tangles

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery 25

25

P A R T 2 What Happens to the Brain in AD

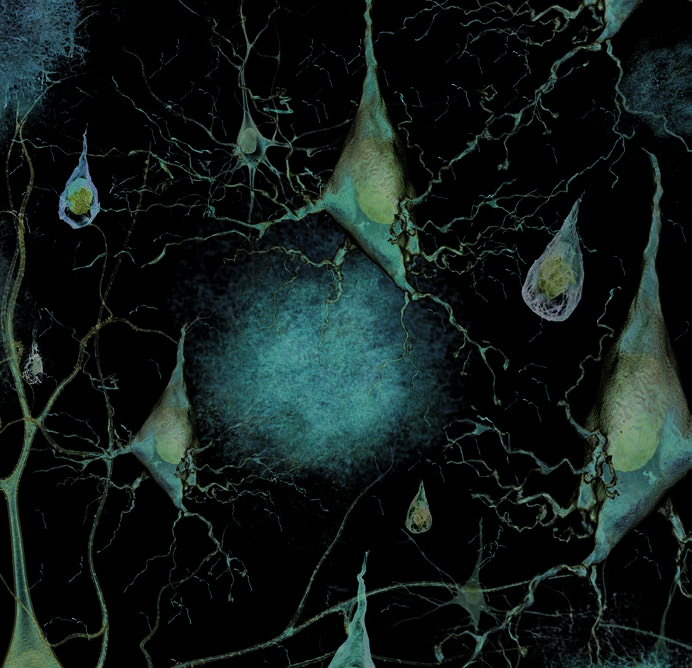

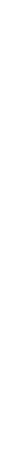

LOSS OF CONNECTION BETWEEN

The AD process not only inhibits communi-

CELLS AND CELL DEATH

cation between neurons but can also damage

The third major feature of AD is the gradual

neurons to the point that they cannot function

loss of connections between neurons. Neurons

prop erly and eventually die. As neurons die

live to communicate with each other, and this

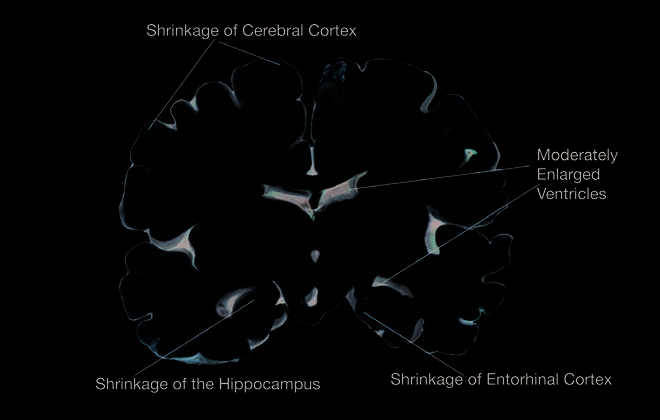

throughout the brain, affected regions begin to

vital function takes place at the synapse. Since

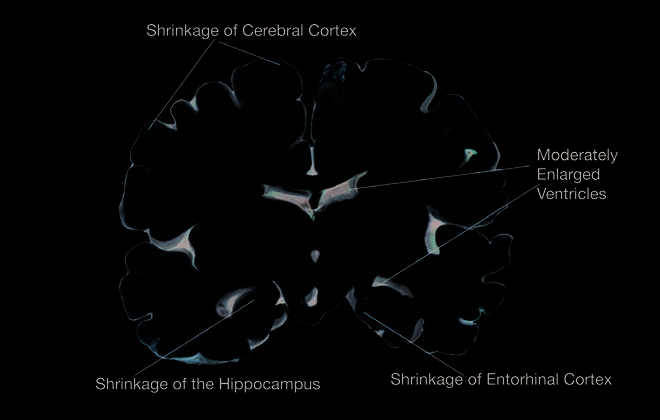

shrink in a process called brain atrophy. By the

the 1980s, new knowledge about plaques and

final stage of AD, damage is widespread, and

tangles has provided important insights into

brain tissue has shrunk significantly.

their possible damage to synapses and on the

development of AD.

Loss of Connection

Between Cells

This illustration shows

the damage caused by AD:

plaques, tangles, and the

loss of connection between

neurons.

26 ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery

Changing Brain

The

in AD

No one knows exactly what starts severity of cognitive problems at diagnosis.

the AD process or why some of the

Although the course of the disease is not the same

normal changes associated with

in every person with AD, symptoms seem to

aging become so much more extreme develop over the same general stages.

and destructive in people with the disease. We

know a lot, however, about what happens in the

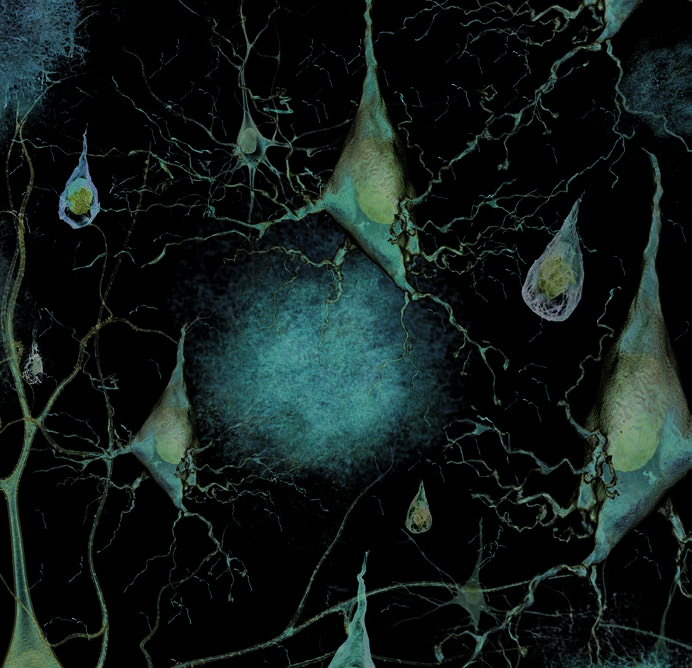

PRECLINICAL AD

brain once AD takes hold and about the physical

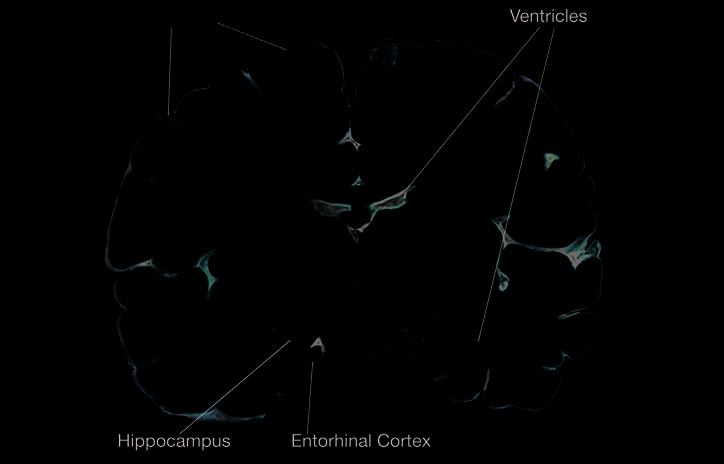

AD begins deep in the brain, in the entorhinal

and mental changes that occur over time. The

cortex, a brain region that is near the hippocampus

time from diagnosis to death varies—as little as

and has direct connections to it. Healthy neurons

3 or 4 years if the person is older than 80 when

in this region begin to work less efficiently, lose

diagnosed to as long as 10 or more years if the

their ability to communicate, and ultimately die.

person is younger. Several other factors besides

This process gradually spreads to the hippocam-

age also affect how long a person will live with

pus, the brain region that plays a major role in

AD. These factors include the person’s sex,

learning and is involved in converting short-term

the presence of other health problems, and the

memories to long-term memories. Affected

regions begin to atrophy. Ventricles, the fluid-

filled spaces inside the brain, begin to enlarge

Preclinical AD

as the process continues.

Scientists believe that these brain changes

begin 10 to 20 years before any clinically

detectable signs or symptoms of forgetful-

ness appear. That’s why they are increasingly

interested in the very early stages of the disease

process. They hope to learn more about what

happens in the brain that sets a person on the

path to developing AD. By knowing more about

the early stages, they also hope to be able to

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery 27

P A R T 2 What Happens to the Brain in AD

PiB and PET

Imagine being able to see deep inside the brain tissue of

a living person. If you could do that, you could find out

whether the AD process was happening many years before

symptoms were evident. This knowledge could have a

profound impact on improving early diagnosis, monitoring

disease progression, and tracking response to treatment.

Scientists have stepped closer to this possibility with the development of a radiolabeled compound called Pittsburgh

Compound B (PiB). PiB binds to beta-amyloid plaques in the

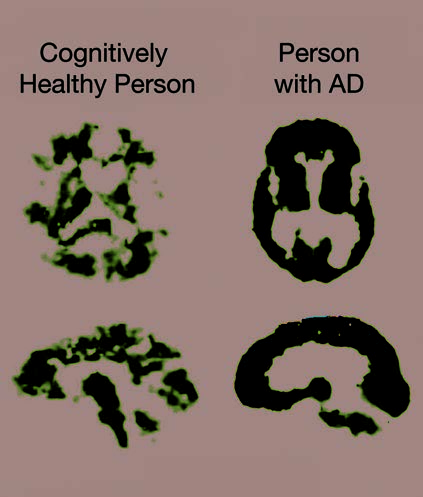

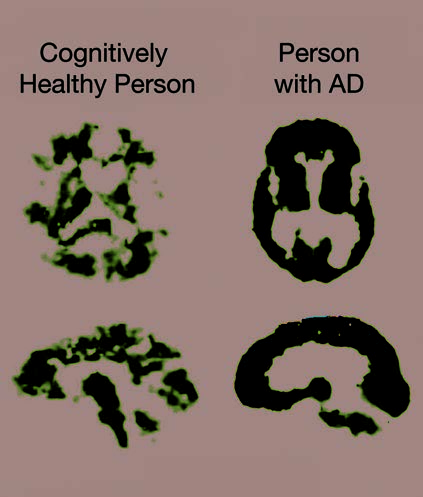

brain and it can be imaged using PET scans. Initial studies showed that people with AD take up more PiB in their brains than do cognitively healthy older people. Since then, scientists have found high levels of PiB in some cognitively healthy people, suggesting that the damage from beta-amyloid may In this PET scan, the red and yellow colors already be underway. The next step will be to follow these

indicate that PiB uptake is higher in the brain

cognitively healthy people who have high PiB levels to see

of the person with AD than in the cognitively

whether they do, in fact, develop AD over time.

healthy person.

develop drugs or other treatments that will

to a substance, the presence of a disease, or the

slow or stop the disease process before significant progression over time of a disease. For example, impairment occurs (see The Search for New

high blood cholesterol is a biomarker for risk of

Treatments on page 54 for more information).

heart disease. Such tools are critical to helping

scientists detect and understand the very early

VERY EARLY SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

signs and symptoms of AD.

At some point, the damage occurring in the brain

begins to show itself in very early clinical signs and Mild Cognitive Impairment symptoms. Much research is being done to identify As some people grow older, they develop memory these early changes, which may be useful in

problems greater than those expected for their age.

predicting dementia or AD. An important part of

But they do not experience the personality changes

this research effort is the development of increas-

or other problems that are characteristic of AD.

ingly sophisticated neuroimaging techniques (see

These people may have a condition called mild

Exciting New Developments in AD Diagnosis

cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI has several

on page 50 for more on neuroimaging) and the use subtypes. The type most associated with memory of biomarkers. Biomarkers are indicators, such as

loss is called amnestic MCI. People with MCI are

changes in sensory abilities, or substances that ap-

a critically important group for research because

pear in body fluids, such as blood, cerebrospinal

fluid, or urine. Biomarkers can indicate exposure

28 ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery

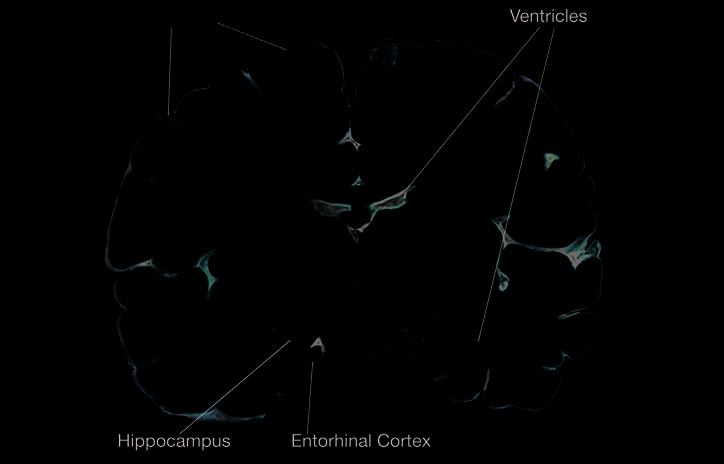

Charting the Course from Healthy Aging to AD

This chart shows cur-

Amnestic MCI:

Cognitive

rent thinking about the

AD brain

memory problems;

decline

evolution from healthy aging

changes start

other cognitive

accelerates

to AD. Researchers view it as

decades before

functions OK;

after AD

a series of events that occur

symptoms

brain compensates

diagnosis

show

for changes

in the brain over many years.

This gradual process, which

results from the combination of

biological, genetic, environ-

Normal age-related

mental, and lifestyle factors,

memory loss

eventually sets some people

Total loss of

on a course to MCI and

independent

possibly AD. Other people,

function

whose genetic makeup may

be the same or different and

who experience a different

Birth 40

60

80 Death

combination of factors over a

Life Course lifetime, continue on a course

Healthy Aging

Amnestic MCI

Clinically Diagnosed AD

of healthy cognitive aging.

a much higher percentage of them go on to de-

AD (see Genetic Factors at Work in AD on

velop AD than do people without these memory

page 36 for more information). And, they have

problems. About 8 of every 10 people who fit the

found that different brain regions appear to

definition of amnestic MCI go on to develop AD

be activated during certain mental activities in

within 7 years. In contrast, 1 to 3 percent of peo-

cognitively healthy people and those with MCI.

ple older than 65 who have normal cognition will These changes appear to be related to the early develop AD in any one year.

stages of cognitive impairment.

However, researchers are not yet able to say

definitively why some people with amnestic MCI

Other Signs of Early AD Development

do not progress to AD, nor can they say who

As scientists have sharpened their focus on the

will or will not go on to develop AD. This raises

early stages of AD, they have begun to see hints of

pressing questions, such as: In cases when MCI

other changes that may signal a developing disease

progresses to AD, what was happening in the brain process. For example, in the Religious Orders Study, that made that transition possible? Can MCI be

a large AD research effort that involves older nuns,

prevented or its progress to AD delayed?

priests, and religious brothers, investigators have

Scientists also have found that genetic

factors may play a role in MCI, as they do in

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery 29

P A R T 2 What Happens to the Brain in AD

explored whether changes in older adults’ ability to

Mild to Moderate AD

move about and use their bodies might be a sign of

early AD. The researchers found that participants

with MCI had more movement difficulties than the

cognitively healthy participants but less than those

with AD. Moreover, those with MCI who had lots

of trouble moving their legs and feet were more

than twice as likely to develop AD as those with

good lower body function.

It is not yet clear why people with MCI might

have these motor function problems, but the

scientists who conducted the study speculate that

they may be a sign that damage to blood vessels in

the brain or damage from AD is accumulating in

areas of the brain responsible for motor function.

If further research shows that some people with

MCI do have motor function problems in addi-

MILD AD

tion to memory problems, the degree of difficulty, As AD spreads through the brain, the number of especially with walking, may help identify those at plaques and tangles grows, shrinkage progresses, risk of progressing to AD.

and more and more of the cerebral cortex is

Other scientists have focused on changes in

affected. Memory loss continues and changes

sensory abilities as possible indicators of early

in other cognitive abilities begin to emerge. The

cognitive problems. For example, in one study they clinical diagnosis of AD is usually made during found associations between a decline in the ability

this stage. Signs of mild AD can include:

to detect odors and cognitive problems or dementia.

These findings are tentative, but they are

■ Memory loss

promising because they suggest that, some day, it

■ Confusion about the location of familiar places

may be possible to develop ways to improve early

(getting lost begins to occur)

detection of MCI or AD. These tools also will help ■ Taking longer than before to accomplish scientists answer questions about causes and very

normal daily tasks

early development of AD, track changes in brain

■ Trouble handling money and paying bills

and cognitive function over time, and ultimately

■ Poor judgment leading to bad decisions

track a person’s response to treatment for AD.

■ Loss of spontaneity and sense of initiative

■ Mood and personality changes, increased

anxiety and/or aggression

In mild AD, a person may seem to be healthy

but is actually having more and more trouble

making sense of the world around him or her. The

realization that something is wrong often comes

gradually to the person and his or her family.

30 ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE Unraveling the Mystery

Accepting these signs as something other than

■ Hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness or

normal and deciding to go for diagnostic tests can

paranoia, irritability

be a big hurdle for people and families. Once this

■ Loss of impulse control (shown through

hurdle is overcome, many families are relieved to

undressing at inappropriate times or places

know what is causing the problems. They also can

or vulgar language)

take comfort in the fact that despite a diagnosis

■ An inability to carry out activities that involve

of MCI or early AD, a person can still make

multiple steps in sequence, such as dressing,

meaningful contributions to his or her family

making a pot of coffee, or setting the table

and to society for a time.

<