CHAPTER II

THE CROSSING OF MARSH AND WATER

Physical Factors Modifying the Formula of the Road: Marsh as the Chief Obstacle to Travel: The Political Results of Marshes: The Crossing of Water Courses: The Origin of the Bridge: The Effect of Bridges upon Roads: The Creation of a Nodal Point: The Function of the Nodal Point in History.

i

So much for the first principle of all: that the Road, like all other human institutions, is best made with brains, and for that second immensely valuable, but too often forgotten, political principle: that if you begin by making your thing wrong it is likely to take root and to remain wrong.

A catalogue of the more important physical factors modifying the formula of the Road (I will come to the political and economic in a moment) is as follows:

Marsh to be traversed; water courses to be traversed; differences of surface other than marsh and water courses; gradients to be dealt with; the obstacle of vegetation to be dealt with.

To these five one may add a factor common to all, and to the making of every road, even in its most primitive stages: (6) the proximity of material (meaning by “proximity” the congeries of all the factors which make for the cheapness of material, for the advantage of using it in a particular place).

Let us take these physical points in their order.

ii

MARSH. It is not always appreciated that the chief obstacle to travel from the beginning of time has been and still remains marsh, which may be defined as soil too sodden for travel, as distinguished from the lands which are boggy in wet weather but passable. Marsh is less striking to the eye, especially to the modern eye, than a stretch of water, much less striking than the apparent obstacle of the sea, or of a bold hill range: it is nevertheless the chief problem presented to the making of a road, because of all natural obstacles it is the only one wholly untraversable by unaided man. Man unaided can climb hills, swim water, work his way through dense undergrowth. But marsh is impassable to him: it is the great original obstacle to progress. If this has not been recognized in the past, and is still little recognized, it is not only because marsh is less striking to the eye than water or hills, but still more because, the original roads established by man in forming his cities, markets, and all the rest of it, being compelled to avoid marsh, we do not often come across the problem even to-day. Partly, also, because very extensive marsh is a rare phenomenon, especially in Western Europe.

But if we look at the map and at history we shall see what that obstacle means. It was marsh which cut off Lancashire from the South of England, and left Lancashire the stronghold of old institutions, especially after the Reformation. It was the marsh of the Lower Thames estuary, now upon the right, now upon the left bank of the river, which forbade a crossing below London. It was marsh which protected the growth of Venice at the earliest and most dangerous moment of its existence. It was marsh which cut off the Western (Polish) civilization from the Eastern (Russian) civilization, and was the main geographical cause of that sharp division in culture which has affected the whole of later European history. We may say that the Russian Orthodox Church and the last Revolution would neither have been, save for the Pinsk Marshes. To take lesser examples, we can see to-day the way in which even our modern ways avoid marsh. The large district of Gargano in Southern Italy has remained largely isolated through marsh upon its flanks.

You may see all over Europe, and even in this well-drained country, primitive roads deflected through marsh as they are not by any other obstacle, and this deflection stamps our road system to this day, in spite of our enormously increased opportunities of road construction. We shall see on a later page the way in which marsh deflected in the dark ages Roman roads at the river crossings in this island.

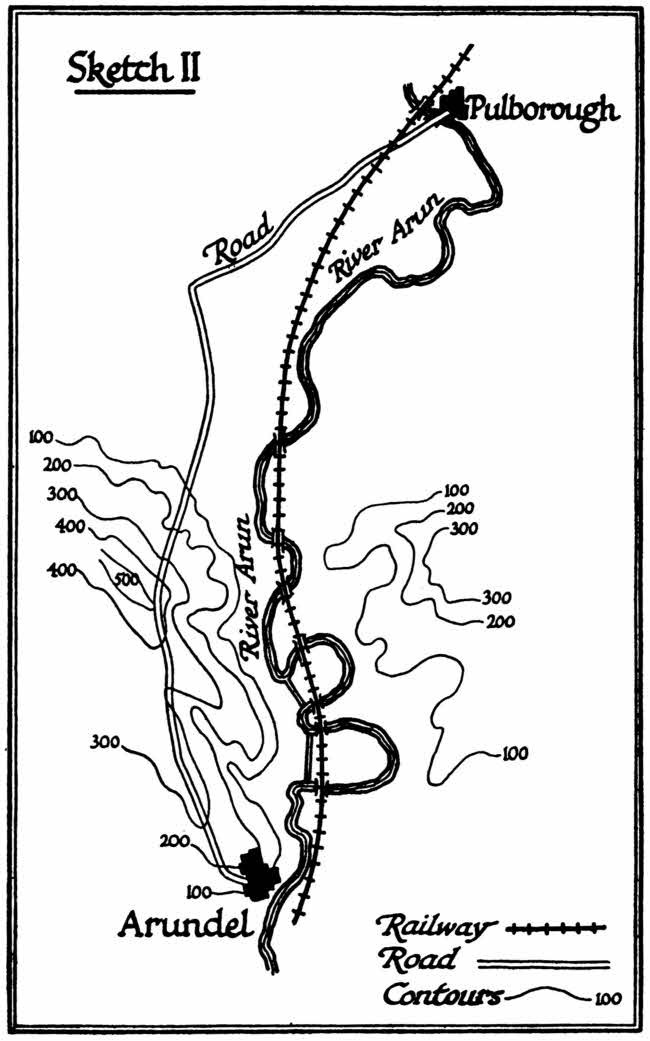

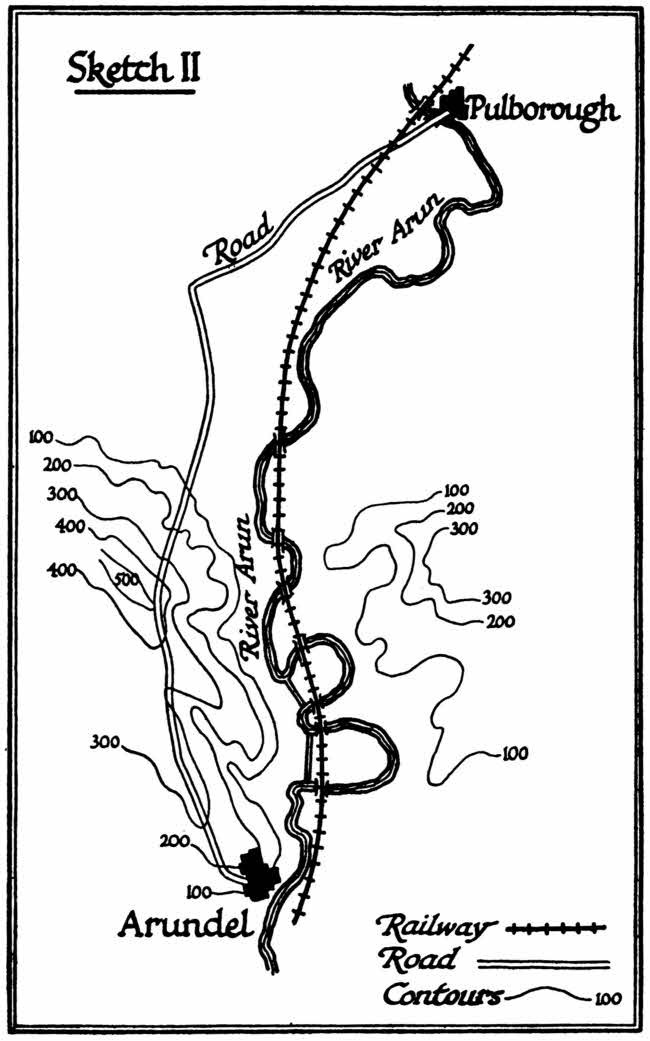

If a special example be required of a road having grown up and remained on an uneconomic trajectory on account of marsh moulding its earlier history, one of the best in England is that of the Arundel road south of Pulborough. Seawards from Pulborough (a landing and crossing-place on the upper River Arun of great antiquity) the next considerable inhabited spot was the port and fortified spur of Arundel. The distance as the crow flies is a short day’s march or less, some ten miles. Now, the road could have been taken in a fairly direct line and everywhere upon the level had it not been for marsh. The marshes bordering the Arun prevented such a construction in early times: the road had to keep to a high, dry bank, then to climb right up to the top of the Downs and fall again upon Arundel. So it remained—having taken root—through all the advances in science: so it still stands to-day. The railway takes the obvious line, but the road, established centuries ago, remains on its former trajectory, climbs up many hundreds of feet, and then drops down again to Arundel, involving in the short distance of ten miles gradients of one in eight and heavy hill-climbing over more than half the distance. A neighbouring example of the extreme importance of the first experiment in the history of a road is seen at Bramber, in the next valley eastward. There a similar situation—the approach landwards from the port of Shoreham—avoids the hills, because at some unknown but very early period a causeway was built at Bramber to negotiate the marsh; and that was because the isolated hill at Bramber afforded such a good opportunity of fortification and blocking the pass that a road was bound to reach it, and even under primitive conditions men were at the labour of making an embankment.

Sketch II

iii

WATER COURSES. The crossing of water courses does not seem to have been originally in the main a search for a ford. It seems to have been rather a search for good taking-off places upon either side, however deep the water in between. The ford was used, of course, wherever it could be, and in it also the hardness of the passage under water was of even more importance than the depth of water: below, say, 4 feet. But the point to note is that often, and probably in the majority of cases, man in the early times took his short cut across water either by swimming or by taking advantage of floating material, and was much more concerned with the hard bank upon either side than with the depth of the stream.

If you take such a very old road as that of the primitive British trackway whose two branches, from Stonehenge and Winchester, unite in what is called the “Pilgrim’s Way” and make for the Straits of Dover, you find this trackway crossing the Mole, the Wey, and the Medway, as also the Darenth, at places where the obvious consideration has been a dry approach upon either side, and not the local shallowness of the stream. (We must remember in this connection that the word “ford” is used at plenty of places where the stream is too deep for crossing on foot: it means simply “a going.” A false etymology here has misled many historians.) Of more importance to the first makers of the Road than the depth of a water course was its swiftness. We have in this country few examples of swift streams of any magnitude, and none of streams so swift as to be impassable or passable with great difficulty, but where such examples occur abroad it is easy to see what a boundary and obstacle a rapid current afforded. It works in all manner of ways to the disadvantage of travel, it makes both swimming and ferrying more difficult (or impossible), it makes bridging either more difficult or (in early times) impossible, it usually connotes great differences of level, sudden floods, etc., and it also usually connotes changes and variety of currents, as well as the destruction of the banks.

At an early stage in the development of the Road came the use of the bridge, and with the bridge the original chief consideration—a dry approach from either side—was emphasized. It is true that fords were bridged as roads developed, but the bridging of a ford is not the normal origin of the bridge. The normal origin of the bridge, if we judge by any one of the original great roads of Europe, is the replacing of a ferry. Men took the obstacle of a river (on account of its length) as something hardly to be turned, save perhaps in its higher reaches. They made straight for it, seeking only firm ground from which to embark and disembark, and established a boat crossing. To this rather than to the ford the bridge succeeded. They bridged it with increasing success as their material science increased in power, and you may see all over Europe the great bridges thrown, not where the river was shallowest nor where it was easiest to traverse for any other reason, but chiefly where the main road led. In other words, the bridge is a function of the Road rather than the Road of the bridge.

Two outstanding examples of this in Europe are London Bridge, perhaps prehistoric, certainly not much less than two thousand years old, and the bridge at Cologne, to which one might add the bridge at Rouen and the bridges of the Island of Paris, which we know to be more than two thousand years old. But it must be remembered that the bridging of a river, even in primitive times, was the next easiest thing to a ferry, and in some circumstances easier even than a ferry. A bridge need not be built of piles. It may be built of boats, and in principle, even over a broad stream, once you could build a boat bridge at all you could build it of almost indefinite length. What would militate against the effort to make a pile bridge were depth and rapidity of stream, but even these, unless the rapidity were very great indeed, did not prevent the throwing of a bridge of boats.

The bridge as an element in the Road plays a very large part which needs some detailed examination: it develops a whole series of results. The object of a bridge is to give continuity and security to travel across an obstacle of depth: usually an obstacle of running water, sometimes a dry ravine. It is but rarely that a bridge is essential to the mere trajectory of a road. In much the greater number of cases its function can be supplied, though far less perfectly, by a ferry, or a ford, or a graded way down into and up from a depression. What the bridge does is to permit of continued traffic, especially continued wheeled traffic, across such obstacles without delay and without trans-shipment, and at the same time to add, up to a maximum of weight, to security; for it is obviously an instrument more secure than the ferry or the ford, especially for heavy weights.

But the bridge has always represented a special economic effort, greater yard for yard than that of the average of the road of which it was a part; and that is why you almost always find it the mark of civilization. A primitive culture can exist for centuries without bridges. The proportion of bridge-building effort to road-building effort varies very much with the physical science of various times. It is less to-day, and was less in Roman times, than in primitive times and in the Middle Ages, because we, like the Roman engineers, expend a far greater economic effort upon the average of the Road, so that the comparative cost of the bridge is less. In primitive times the bridge was something of a feat, its construction as measured in effort was equivalent to many miles of road, its builder a public benefactor, and its building an event of note. This is so true that in some languages which have come down but little changed from primitive times the word for “bridge” is found to be a foreign word, as though the institution were not sufficiently common before the advent of some civilized conqueror to have acquired a special name; and in all primitive societies the bridge is rare.

This comparatively high cost of the bridge has had certain effects on the history and in the appearance of our roads which are worth noting. In the first place, the bridge tends to be a “gut.” When the throwing of a bridge was equivalent in expense to several miles of the existing road it was a great saving to make it narrow: only one vehicle to pass at a time, with side refuges at the piles when the passage of two vehicles in opposing directions was unavoidable.

Again, bridges tended, especially in times of low economic development, to introduce a sudden high gradient. The elliptical arch was, if not unknown, at any rate very rare before the Renaissance, and where the plain semi-circular arch alone was used a flat bridge involved, if the crossing were of any width, a great number of piles, and therefore an added expense. The difficulty was met in the majority of cases by lessening the number of piles, especially towards the centre, where there was a greater depth, consequently increasing the span there, and consequently, in a semi-circular arch, increasing its height correspondingly. The result was that the bridge introduced a sudden hillock into the Road, and that feature you find all over Western Europe up to quite modern times, with many survivals remaining, especially in Spain. In some of the very early bridges in the poorer districts, or on the less used roads, the exaggeration is fantastic. I know of one over the Gallego, near Huesca, where the pitch is so steep that it baulks a car.

There were particular structures—that of London is an example in point—where the disadvantage of a gradient was avoided at great expense because a mass of traffic and merchandise made it worth while. London Bridge was carried on a great number of arches precisely in order to avoid this element of gradient. A side-effect of this was the blocking of the stream and great difficulty for boats in “shooting” the arches on a tide; but this drawback to river traffic was thought worth while as the price of a level road.

Another reason which often led to the expensive flat stone bridge was its replacing an old wooden pile bridge. The wooden pile bridge had no cause for creating a gradient. On the whole it was cheaper to keep it exactly level, and as low as possible consistent with the rise of the water. Where such a structure had preceded a stone bridge the habit of a level road was continued, even at the expense of many piles and arches.

A third effect of the bridge upon the Road, also due to its comparative expense, was the convergence of roads towards bridges, established or even only planned. You will perpetually find up and down Europe the approaches to a town from two or more directions merged into a common road just at the entry to a bridge, in order to save the expense of two crossings, though at an extra expense of space and time; thus, Abbeville, Caen (a very striking example, with three converging roads on each side of the bridge), London—the chief example in Europe—Saragossa, with the two main roads from south and west converging on its bridge—all “gather” roads after this fashion.

But the effects of the bridge upon the mere trajectory of a road, upon its surface and contour, were far less than were its political and military effects. Though land armies were always tied to roads more or less, it was possible to leave the road for short distances under stress or for the sake of strategy. Cavalry continually did so for great stretches, and infantry could do so occasionally. But a bridge acted like a magnet. The defence of a bridge was the defence of a point which an army in force was always compelled to use, and the term “bridge head”—that is, the holding of the space on the further side of the bridge, thus commanding the passage—is an example of its permanent military function.

A bridge was, for the same reason, a natural place of toll. Merchandise had to use it, and the same requirement of continual repair which often entailed a permanent post at a bridge gave the opportunity for using that post for the raising of taxation. All through the end of the Roman Empire and the Dark and Middle Ages this function of the bridge is most prominent.

iv

But most important of all the effects of the bridge is its creation of a nodal point, that is, a knot or crossing of ways. The bridge effects this in two fashions: firstly by that tendency to a convergence of roads upon the bridge which I have just noted, and secondly, and much more important, by the transverse of the bridge and the river. A river is also a high road if it is in any way navigable. Therefore, wherever a land road crosses a river and establishes a bridge you get a crossways of communications. At such a point, where many avenues of approach meet, and whence opportunities of travel to different places radiate, you have what is called in political geography a Nodal Point.

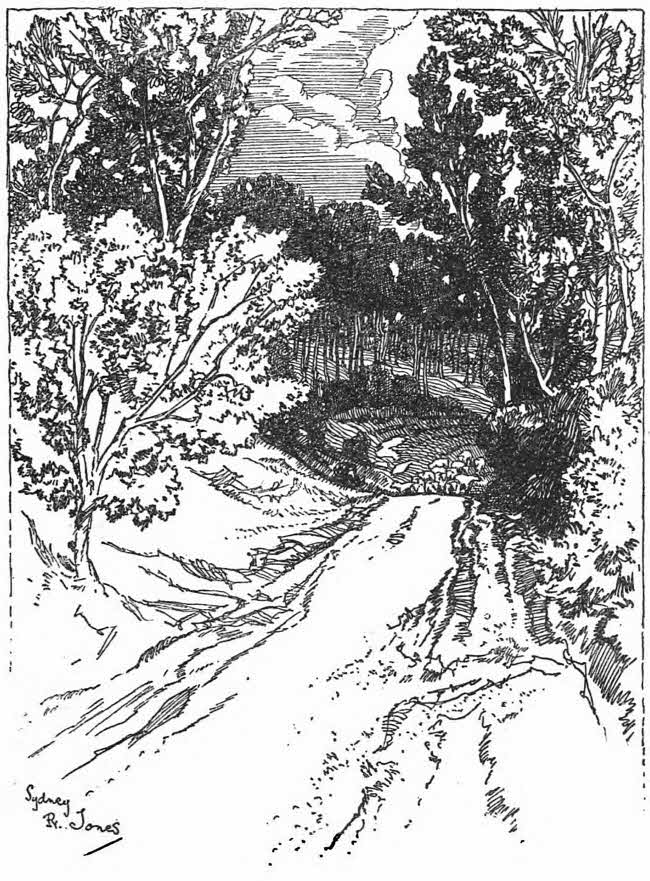

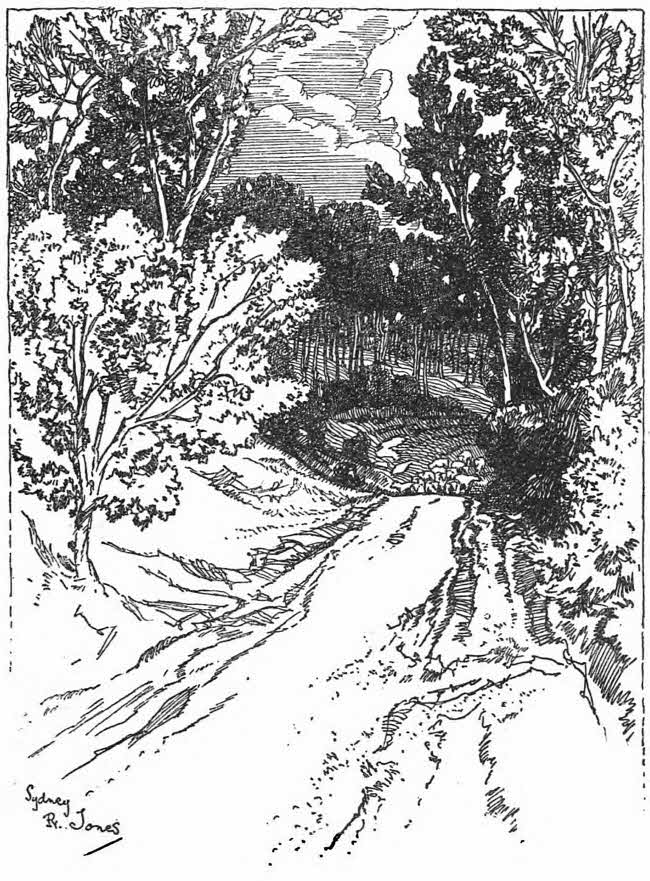

ICKNIELD STREET in the Oxfordshire Chilterns

Now, the nodal point is of such importance that it merits particular attention. The nodal point, especially if it is established by a bridge, has two great functions in history. It determines the strategy of campaigns (and alters even the tactics of actions), it determines the growth of towns. It has been said that London was made by its bridge. Whether there was a settlement (there probably was) upon the gravelly hill which approached the river from the north, before any bridge was thrown across the tidal Thames, we do not know; but it is certain that the throwing of this bridge gave London its opportunity for development, and what is true of London is true of Paris, of Rouen, of Maestricht, of Cologne, and of twenty other great urban centres in our civilization. Strategically, a commander holding a nodal point retains the opportunity of moving along any one of many lines of movement, and at the same time denies the opportunity of junction to his enemies. To put it in its simplest form, a commander holding a nodal point and concentrated there can prevent the concentration of two fractions of his enemy along any two roads radiating from that nodal point. He can himself march up each of these consecutively and defeat the two fractions of his enemy in detail. That is the simplest possible case, and it can be developed into any amount of detail and intricacy.

The bridge is the point where the commerce up and down stream crosses the road-commerce transversely to the river-commerce, and the nodal point of the bridge establishes a market. But that nodal point has other characters even more important to civilian life. It creates a point of trans-shipment, where goods must be transferred from the water vehicle to the land vehicle. In their transference you have the political opportunity of examination and toll, and, if necessary, interception; and you also have, of course, the whole of the middleman business of dealing with and passing through the goods—you have the depot and the warehousing and all the adjuncts of a built-up commercial centre and a market.

But the bridge as a nodal point has yet another occasional function which has marked all history. That function it exercises when it is the lowest bridge upon a great navigable river. Such a bridge—the bridge of Rome for instance, the bridge of London, the bridge of Gloucester, the bridge of Newcastle, etc.—has been the making of inland ports. It must be remembered that before the advent of the railway, or at any rate before the organization of rapid and easy road travel, it was to the interest of sea-borne trade to penetrate into the heart of the country as far as possible. You avoided the cost of trans-shipment, and you had a much cheaper means of conveyance than anything that went by land. But the first permanent bridge across a waterway blocked the further progress up-stream of sea-borne traffic. Therefore there was a tendency to keep this first bridge well up-stream. Further, whenever it was made, it tended to create a glut of traffic at this point of section. The cargoes from the sea came here and could go no further, and this last function of the bridge is perhaps of all its historical functions the most important. Even where a river is very rapid, as the Tiber, the first bridge has some effect. Where it is tidal it is, of course, as in the cases we have just quoted, of the greatest effect, and usually on the great tidal waterways the first bridge will be found not indeed at the limit of the tide, for there the water would be too shallow, but in the last reaches. There are cases (Rochester is one) where the road has proved more important than the stream, where a bridge was imposed very low down in the tideway, but it has there fulfilled the same function of creating a market and a town. There are cases (Antwerp, Bordeaux, and Philadelphia are examples) where a secure harbour and good wharfage made the inland market and town in the absence of such an obstacle as the first bridge; but in the greater number of navigable rivers, even in so narrow a stream as that of Seville, the bridge makes the port and the town, as one can see by adding to the examples already given Nantes, Montreuil, Glasgow, etc.

There is a little note on the crossing of water courses which is curious and interesting in the history of roads. Since the crossing is always an effort, or, in economic terms, an expense, to be avoided as much as possible, the Road naturally avoids a double crossing, but, on the other hand, an island is a stronghold, and even a peninsula where two rivers meet is a potential stronghold. Therefore you have in the history of all early European roads a sort of dilemma, the first travellers debating, as it were, whether the occasion were sufficiently important to warrant the double crossing of the stream. At Reading, Lyons, Melun, notably at Paris, and in dozens of other places, the presence of the stronghold made it worth while for the Road to visit the place in spite of the double crossing, whether to an island or to the meeting of two streams. But in much the majority of cases the Road was deflected from its simplest line to a point below the meeting of two streams so as to avoid the double effort, and the occasion explains many a deflection which otherwise would seem to have no reason.