CHAPTER III

PASSABILITY

The Choice of Soils: Following the Gravel or the Chalk: Conditions in the South and East: The Obstacle of Gradient: The Early Vogue of Steep Gradients “The Other Side of the Hill”: The Modern Importance of Gradient: Passes or Gaps in Hill Country.

i

To the next physical factor modifying the formula of the Road we have given the name: DIFFERENCES OF SURFACE OTHER THAN MARSH AND WATER COURSES. The differences of surface other than marsh or water courses affect the trajectory of a road in several ways: first and originally in its passability to human travel on foot or with beasts of burden, or later with wheeled vehicles, and here the two factors were hardness and evenness. But there was a great contrast in the obstacles of the North and the South of our civilization. In the North, and especially in England, damp was the enemy. For a trajectory to be used in all seasons and in all weather sand and chalk at once suggested themselves. Clay can be used only in the dry season. The various soils determined the first trackway and impose themselves visibly upon the map of our oldest roads.

For instance, the road down the upper Wey to Farnham is, in its oldest form, a deliberate picking out of long gravelly stretches in the bed of the valley. On a geological map you can trace this road picking its way from gravel patch to gravel patch almost as a man crosses a stream by stepping stones. It leaps, as it were, from one gravelly stretch to another, and in each keeps to the gravel as long as it can. For the same reason a primitive road will follow the South, or sunny, side of a wood or of a ridge of land, so that the surface may dry as soon as possible after rain.

When the use of artificial material for the surface of the track became common this question of quality of soil was somewhat modified, but its essential was retained; for what made bad going (in the North, and particularly in Britain) being heavy soil, that same kind of land, which interfered with foot or pack-horse travel, swallowed up material. It was a less grave inconvenience than in the times before artificial material was used, but it was still an inconvenience expressed in the shape of expense; and nearly all the original trackways continued to take account of this factor long after the use of artificial material had been introduced. The earliest of all, of course, follow the dry ridges, and in particular the chalk.

One may say, with slight exaggeration, that the chalk was the essential factor in the building up of British communications before the Roman civilization came. If you take a geological map of England you may see the great chalk ridges radiating in a sort of whorl from a centre in Salisbury Plain, and providing dry going to the Channel, the Straits of Dover, and across the Thames valley at Streatley right on to Norfolk.

Another example of a road taking advantage of dryness of surface is the straight line leading to Lincoln northwards, everywhere following that peculiar isolated ridge, with low-lying ground upon the left and marsh upon the right. Another very striking one is the Hog’s Back, where from one low-lying point to another (Guildford to Farnham) the primitive track deliberately rises and follows the summit of a high hill between rather than the wetter ground upon the slopes, though here there is an alternative upon the southern, or sunny, slope where the trackway leads through to St. Catherine’s Chapel. This is a modern example of the way in which a primitive track imposes itself upon posterity. To this day your motorist climbs up that roof of a house out of Guildford and goes down the steep on to Farnham because countless generations ago his ancestor could only be certain upon that height of dry ground.

In the South (which does not concern this essay) the great obstacle in the way of soil is not marsh, but sand. That is something of which we have here no experience, but the tracks of nearly all Western Islam are dependent upon it. Drift sand is not so impassable as marsh by any means, but it is terrible going. North and South of Atlas the knowledge of how this kind of soil may be avoided is half the business of establishing a primitive road.

An interesting case of surface (but one which is rarely met with in this country) common in dry countries where the rare rainfall is sudden and intense, and where temporary water courses carve out the friable soil, is the inconvenience due to what are called in some parts of the East “nullahs”—that is, the dry beds of such water courses or the sudden depressions made by what were formerly water courses now dried up through a change of climate. The banks of these are often so steep and their depth so considerable that the making of a plain, straight trajectory across such a country would, even under modern conditions, not be worth the labour expended. It would mean continual bridging, or continual embankment. One of the effects of this type of surface is the inordinate winding of all the roads, and even, alternatively, the absence of roads perpendicular to the fall of the land, and the establishment of communications along the line of fall rather than across it. One can see this very conspicuously in Morocco, where there are whole districts, a couple of days’ march across, the trails of which are determined by this accident. A special example of the same kind of thing is to be found in any hill range where a number of narrow spurs project towards the plain. The Road hardly ever runs parallel to the range across these spurs. It nearly always runs down the valleys or along the plain at their foot, and that although there be, as there usually are, in each valley centres of population which need to be linked up with the neighbouring parallel valleys.

ii

GRADIENTS. The obstacle of gradient the “minimum of vertical effort” is the most evident of all the factors which modify the trajectory of a road; yet it is, upon the whole, the most complex. To determine the minimum of effort you have to find a formula consisting of many factors, some of which I have already enumerated in the opening words of this essay. In the first place, you have to consider the average nature of the travel to be served. The Road used by men on foot without burdens, by men on foot with burdens, by pack animals, by wheeled vehicles, etc., must conform itself, on the whole, to the least gradient useful to those who travel by it, but that “on the whole” least gradient is a factor by no means easy to determine. It depends not only upon the nature of the instruments of travel, but upon habit, upon vigour, and to some extent upon surface. It depends also on the proportionate use of the Road. You cannot sacrifice ninety-nine travellers to the special weakness of one.

There is also the question of durability. A primitive road, taking a very steep gradient, will be more durable than one taking a lesser gradient round the slopes of a hill and subject to falls from above and to degradation down the slope below; it will need less upkeep, for it is always shorter—and this last consideration explains what would otherwise be inexplicable: the extraordinarily steep gradients which primitive roads and even the roads of a high civilization will take.

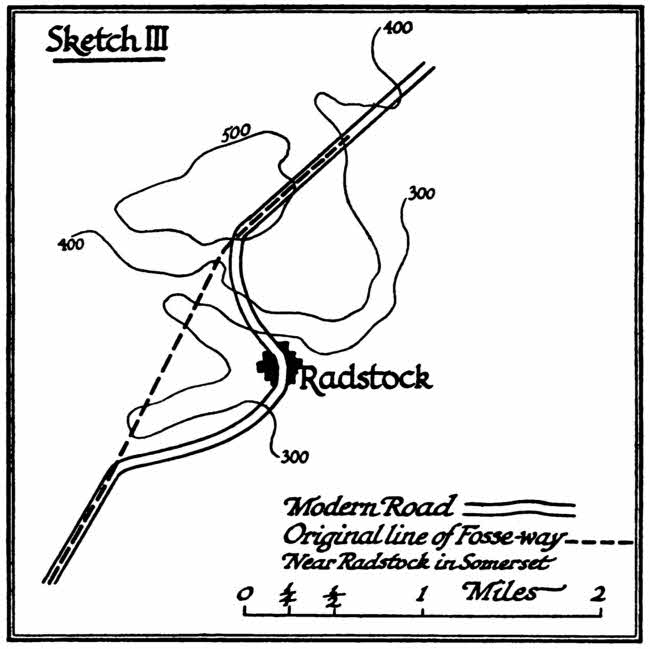

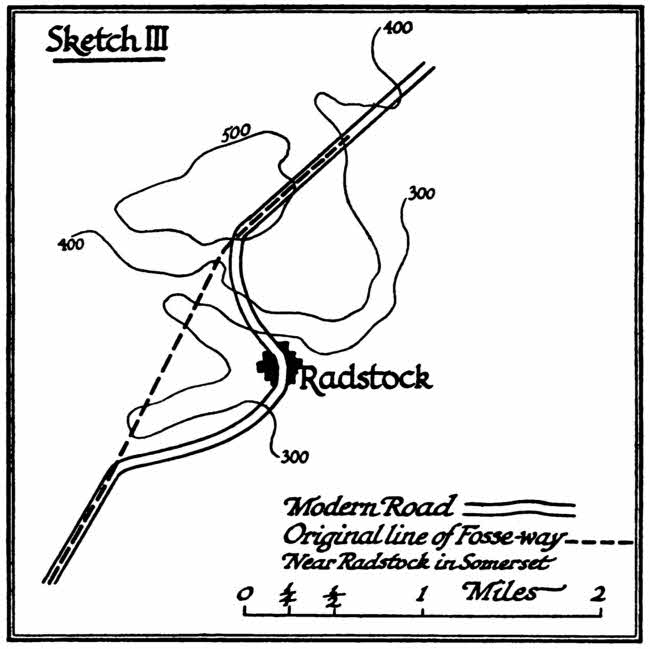

One of the best examples of this in England is the behaviour of the Fosse Way in the neighbourhood of Radstock in Somerset. Here the original road was presumably a prehistoric track, but we know that it was carefully remodelled by the high Roman civilization. It must have been used for the great mass of travel during four hundred years from the first occupation of the West of England by the Romans about A.D. 50 to the breakdown about 450, and right on into the Dark Ages—that is, for not less than one thousand years. During the first half of this time (and especially during the first third) it had to carry the travel of a very full, well-developed, and complex society to one of the most important centres of its wealth, the town of Bath. Yet the road goes up the most astonishing gradients.

Sketch III

Somehow or other, these gradients were normally used—but it is a puzzle to say how. The modern road has frankly abandoned the effort, and takes a long sweep round both sides of the valley at a gradient of about 1 in 12. Even so, it is quite steep enough for our modern methods of travel.

The question of gradient is complicated, again, by another variable which makes the solution of the problem much more intricate than the discovery of minimum effort upon a particular gradient. You have to consider not only the uphill or downhill upon a given slope, but the type of further uphill and downhill to which your road, once established on that slope, is leading you. It is not enough to determine your best formula under such and such conditions of travel for overcoming one side of the obstacle. You have also to ask yourself whether, having got your best uphill road, you may not have led the traveller to an impossible position on the further side. Extreme cases of this one often sees in the Jura range, where the hills are shaped like waves in a storm: a steep escarpment upon the eastern side, very difficult to go up or down, and an easy slope upon the western. Here you have to balance the advantage of your gradient upon the one side with the advantage of the gradient that you will find upon the other, and, of course, to direct your line principally with a view to travel on the more difficult steeper side. That is why you often find yourself following in the Jura a road which goes up the easy western side by an apparently over-steep trajectory: you wonder why the road does not take some obviously easier line which lies below you. The reason you only discover upon reaching the summit and seeing the precipitous escarpment overhanging the eastern valley—your road has made for some exceptional advantage down this cliff, some cleft, which an easier advance from the west would not have hit. A balance has to be struck between the advantage of gradients on both sides of the hill, save in the rare cases where a range (such as the Vosges) is symmetrical and gives you equal gradients upon either slope.

That balance is always a matter of careful calculation. Where it has been brought to a fine art is, of course, in surveying for a modern railroad, for there the slightest differences of gradient make such a vast difference in the expense of working that the discovery of a true minimum over an obstacle of hill country is of the first importance.

iii

There is hardly any factor in connection with the theory of the road which needs more material modification as civilization changes than this factor of gradient. The sharpest contrast in the whole of history is that which I have just mentioned: that of the railroads. Men suddenly found themselves possessed of a new instrument which enormously multiplied their power on the flat and yet was quite incapable of anything like the old gradients. Going level or on very slight gradients it could give them travel far more rapid and inexpensive than any that had been known before, but one in fifty bothered it badly, one in thirty was wholly unnatural, and the existing gradients of one in ten, eight, six, were out of the question. Further, the least inclination increased all difficulties, and the addition of inclination produced these difficulties in more than a geometrical progression. The result was the revolution whose effects we see about us everywhere: the tunnel, the cutting, the embankment.

To-day, a couple of generations after that revolution, there comes the new problem of the internal-combustion engine, where the gradient again appears in a new light.

The motor takes gradients far steeper than the rail. Its difficulties are not increased in the same ratio. But it cannot always deal with the horse road. Lynton and Lynmouth and their Devonshire valley form perhaps the best example of this in Great Britain. You have here terrible gradients which were just possible for the horse vehicle and are hardly possible for the motor vehicle, and you have the new road round by Watersmeet attempting partially, but not entirely, to solve the problem.

A special case in this general category of gradients, and one much more complex than appears at first sight, is the case of the pass, or gap. Men have always naturally made for any notch in a line of hills to save themselves the effort of higher climbing. It began with foot travel, and has continued right on throughout the history of the Road. In high mountains provided with low passes the use of a saddle in the range was obvious and often necessary; but there were disadvantages even in that apparently unexceptionable rule. One was the question just dealt with of the double slope: the consideration of the other side—the most obvious pass from the one side did not necessarily lead to the best descent upon the other.

Another was the conformation of many ranges, which is such that the approach to the ridge is much steeper at the summit of a “col” or pass than it is by tracks to one side.

This is a paradox which people living in easy hill-lands have difficulty in appreciating. The Alps especially show roads which puzzle us (who are of a gentler landscape) when we follow them: yet the principle is simple and dependent upon the geological formation of most new mountain ranges, which present a hard core, forming their central ridge. The softer ground wears away on either side of the valley: the ridge remains. The effect is that a direct approach to the notch in the range would give impossible gradients in the last few hundred yards, and therefore the road must gradually curve round by a side of the valley.

A third exceptional case is that of trajectories where the minimum of effort is only to be found by going right over the very summit of the highest hill in your neighbourhood. Lastly, there is the curious case of a pass where it is to the advantage of the road to avoid the lowest passage of the range and to take a line to one side above it.

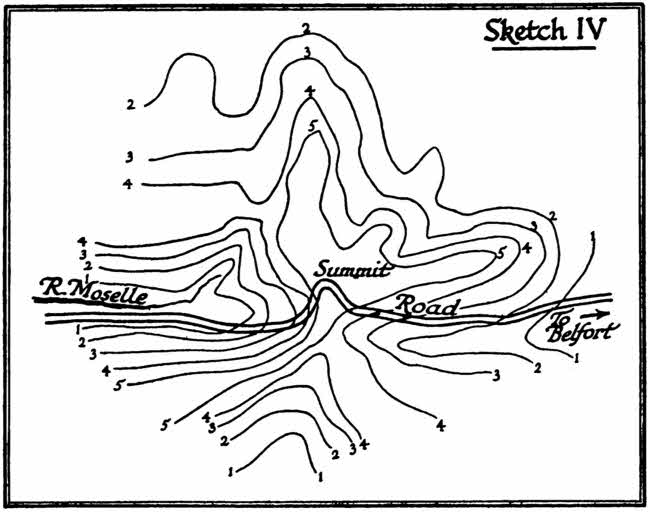

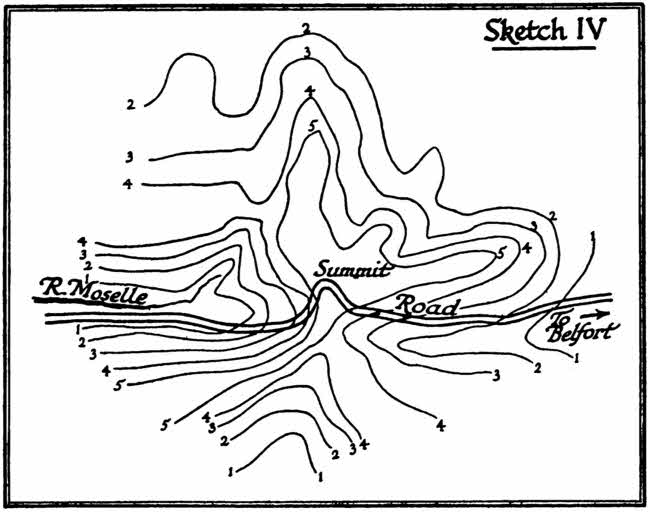

As examples of these last two paradoxical points I may quote the pass of Sallent in the Pyrenees and the exceedingly important road from the valley of the Moselle to the valley of Belfort in the Vosges.

In the case of the pass of Sallent there was an obvious notch in the range, which was used from the very earliest times till just the other day. It was through this that the armies of the Moors poured in the eighth century for their attempted conquest of Europe, when they invaded France and nearly reached the Loire. So late as within living memory it was the regular track from the valley of the Gallego to that of Gabas. Now, the modern road, after careful survey, has been constructed to cross the mountain summit somewhat to the west, and a good three hundred feet higher than the old pass. Why was this? It was because the notch of Sallent had a very steep approach in the last few hundred yards upon either side, and the minimum of effort, at any rate for wheeled vehicles of the modern type, was found in taking a lesser gradient to one side, although it involved a much higher climb. The case of the road from the Moselle valley to Belfort in the Vosges is even more remarkable, for one would have said at first asking that no such case could exist: one would have said that a minimum of effort could never be reached by going over the very highest summit in your neighbourhood, but it is so when you deal with what I will call a “star” mountain, as will be seen at once from the following elements.

Sketch IV

Here the contours are such that had the road deflected to the west or the east in order to avoid the highest summit, it would have been compelled either to a very long detour (involving in any case nearly as high a climb) or to a series of steep and profound ups and downs over the spurs of the mountain. The line taken from the Moselle to Belfort on the other side goes within a few feet of the highest point on the hill, and is yet the line of least effort from one point to the other. It is an excellent example of the way in which the formula of minimum effort, when it is thought out, may be quite different from what mere habit would have produced.