CHAPTER VII

THE ROAD IN HISTORY

Through the Dim Ages: The Characteristics of the English Road: Absence of Plan: A Local instead of a National System Leading to the Present Crisis.

i

The general theory of the Road having been discussed, we may next turn to the particular case of THE ENGLISH ROAD, my second and concluding section. The English Road has, as we shall see, highly-marked characteristics of its own which are of immediate concern to us at this revolutionary moment in the economic history of the State.

The fortunes of the English Road followed, of course, the story of all the other main English institutions in their outline. Just as you had the pre-Roman barbaric period, then the Roman period, then the Dark Ages in the general history of the State, so you had the British trackway, the Roman Road, and the continued use during the continued decline of the latter as material civilization fell away after the fifth century. The spring of the Middle Ages gave you the renaissance of the Road. The Black Death, which is the watershed of the Middle Ages, breaks the history of the Road just as it breaks the history of the language. French dies out: all England is speaking English in the generation after the Black Death, and there is a great change throughout society. That change is marked on the roads by a considerable decline in travel, coupled with the use of better means of transport—a paradox to which our times are not accustomed. But you get a good deal of that in the Middle Ages. You have, for instance, a decline of wealth in the monasteries, and yet more detailed building in the monasteries; a bad decline in manuscript writing, both with regard to accuracy and legibility, and yet an increase in the amount written. So far as we can judge from our very imperfect evidence, after the Black Death (the middle of the fourteenth century) the volume of traffic upon the roads of England tends to get less, and perhaps the surface also deteriorates, though that is more doubtful.

The Reformation, and especially the dissolution of the monasteries, is the next great date. The violent revolution imposed A.D. 1536-40 on every department of the national life affects the roads as it affects all else. In general, the Reformation, especially through the dissolution of the monasteries, had the following economic effects upon England:

(1) Customary economic action tended to be replaced, after the change, by competitive economic action;

(2) Corporate action tended to be replaced by individual action;

(3) The principal land-owning class—the squires—became much wealthier than they had been in proportion to the rest of the community.

The accommodation of these three main economic facts had the general result of substituting more and more statutory duties in local affairs for customary duties, and it affected the roads thus: where the local community had, in a customary fashion, kept up the local road as part of the old social habit the new lay owner refused. He was averse to the outlay, the Crown had less control over him, and as he was running the whole thing on an idea of profit and loss every outlay was cut by him as much as possible.

There was at the same time a revolution in agriculture, a falling off of population, the throwing together of small holdings, the growth of grazing, and the decline of tillage.

You consequently get, through the common action of all these influences combined, in the middle of the Reformation period the first interference of the central Government by direct statute in the making and conservation of the English road system. This famous piece of legislation (2 and 3 Philip and Mary, Cap. VIII) is familiar to all who deal with the law and history of the highway. It governed the constitution and maintenance of English roads right down to the great modern change in the same which falls under the general term “turnpike.” These are the main stages in the story of the Road in this island up to the present moment, when, apparently, another stage has opened.

We have for these seven chapters very different information: on the first nothing but conjecture, on the second a considerable body of evidence, on the third again conjecture, and on the fourth conjecture, though conjecture filled in from the indirect evidence of historical event. For the second mediaeval period we have even less evidence than for the first. Our knowledge begins to grow after the increase of wheeled traffic, and with the early eighteenth century becomes for the first time full and detailed.

ii

We will now follow this development.

The English Road has a character of its own which clearly differentiates it from the other road systems of Western Europe. So sharp is the distinction that, since modern travel recovered the use of the road through petrol traffic, the new type of road he discovers is, after the language, the most striking novelty affecting the foreigner on his arrival.

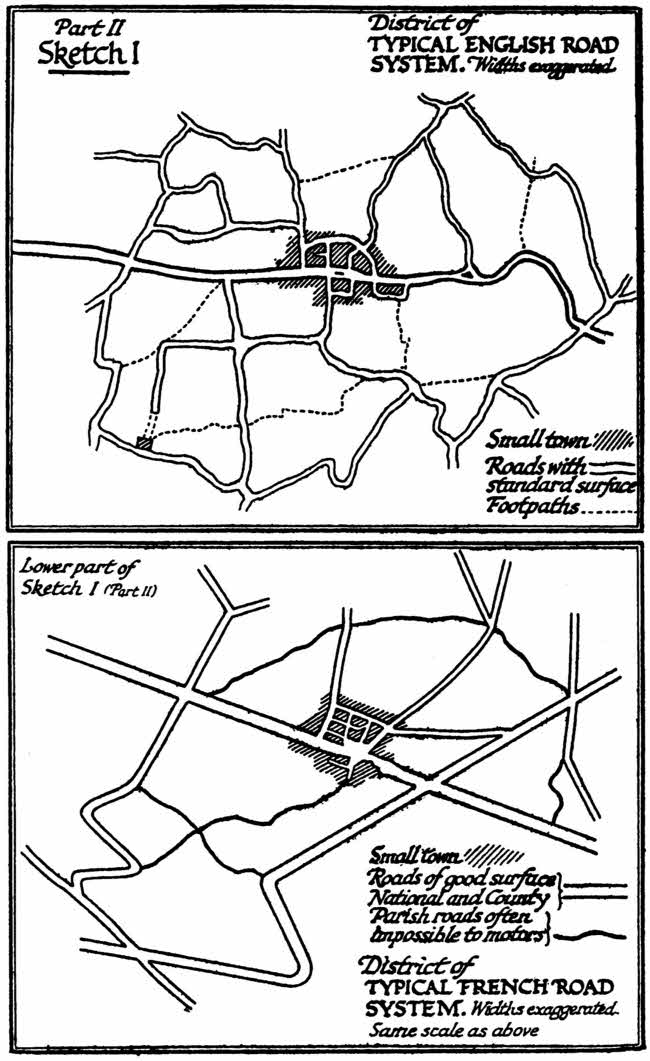

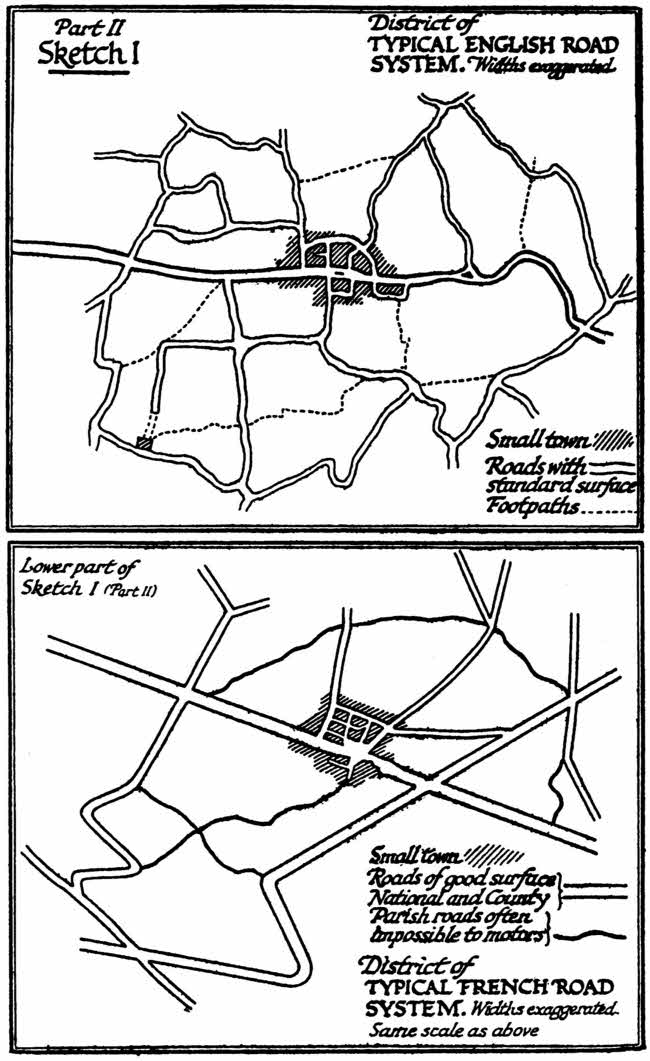

Part II, Sketch I, District of TYPICAL ENGLISH ROAD SYSTEM. Widths exaggerated.

Lower part of Sketch I (Part II), District of TYPICAL FRENCH ROAD SYSTEM. Widths exaggerated. Same scale as above

Abroad, the French model—recovered from the Roman tradition, remodelled in the late seventeenth century, and vastly developed in the nineteenth—has impressed itself everywhere: the Road is there built up on a framework of very broad, straight main ways, carefully graded, proceeding everywhere upon one plan. These are connected by a subsidiary net of country ways less direct and less broad, but all carefully planned and graded, and these in turn by local lanes of all surfaces and gradients and gauges, dependent upon parish rates and betraying by their irregularity their independence of the national system.

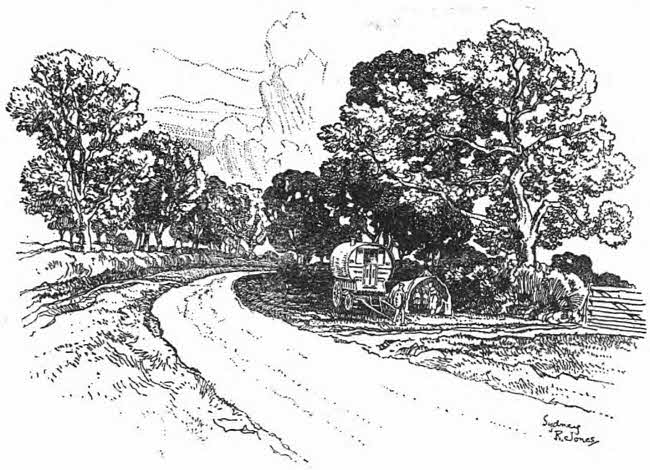

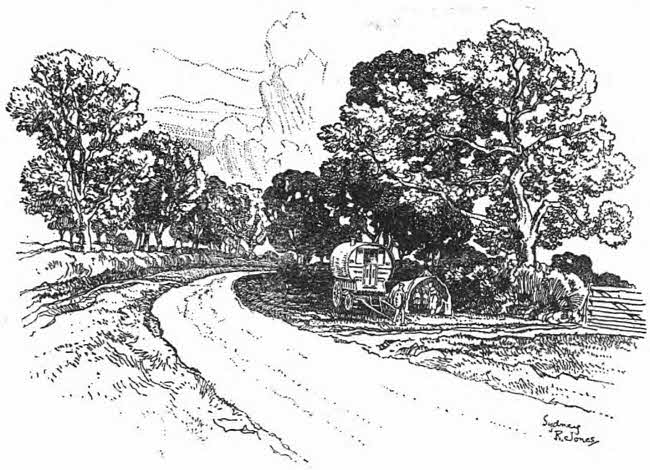

TYPICAL ENGLISH LANE

Here the scheme is contradicted at every point. A long stretch dead straight is very rare: when it is found it is due to some accident of local choice. The surface differs not as between the main road and local road, but indiscriminately: a small parish way will often have a better surface than the main road it joins. The gauge is haphazard: the main road between the capital and some great port will go through the most surprising changes in breadth, here appearing as the narrow high street of a suburb, and there, a few miles on, spreading to 50 feet upon an open heath, then again turning abruptly round the sharp right-angle corners and between the irregular frontages of a village. The English roads are far more numerous, the mileage of good road surface to the hundred square miles far greater, than abroad. Yet not one of them is planned throughout. They all twist, the lesser ones winding perpetually and usually without any reason of their own, compelled to such anomalies by the custom of older paths, by enclosures, by encroachments. For the most part these roads, from the most important to the least, are “blind,” that is, bounded by obstacles which mask the approach of corners and conceal the country on either side: a very pronounced national characteristic, due mainly to the use of hedges upon the more fertile land. The grading is never continuous—the main roads in which this feature has been most thoroughly looked to yet have astonishing exceptions of 1 in 9, 1 in 8. The bridges are of varying strength, half of them bearing warnings that they are dangerous to heavy vehicles.

When we seek the origin of this strange mixture of serviceable and unserviceable in the English road system we discover it in the political history of the country. The English hedged roads yield their more pleasing landscape, they have more length to the square mile than those abroad, they are haphazard in gauge and gradient (only half planned), they have such excellent surface (and that independently of their importance), such a strange assortment of bridges, such abrupt and blind corners—all because the Road, like every other institution, is a function of society, and because English society proceeded on special political lines of its own after the Reformation.

Like the road systems of every other country, that of England arose from the great Roman military ways. It went through exactly the same phases of decline as those of the neighbouring Continent, it had the same new development in the Middle Ages, it ran through open fields mainly. A man put down on an English road of Henry VIII or Elizabeth’s day would have marked no great distinction between its character and those of a Flanders or a Breton or a Provençal road, or the roads of the Rhine.

But with the seventeenth century the profound change which had worked for a hundred years throughout all English life appeared in the Road. The monarchy fell. A national road system became impossible. The local landlords took command of society. The local road was the only basis for development. Commons were enclosed, co-operative village farming gradually disappeared, the hedges everywhere increased in number, cutting up the old open fields. Any extension of communication could only come through the linking up of tortuous village ways.

Then came the industrial revolution, the exploitation of better surface through the turnpike, the epoch of Telford and Macadam. Lastly, the huge increase of the great towns in the middle and later nineteenth century, the coming of the internal combustion engine, and the present crisis. For we have come to a crisis to-day in the history of the English Road. It must be changed—or supplemented—under peril of such congestion as will strangle travel and interchange: that is the interest of the subject to-day.

I propose, therefore, in what follows to consider, first, how this particular character in the English Road developed: what were the agencies which gradually made it so different from the road of the neighbouring Continent: next, to sketch very briefly and only in its bare outline the history of the English Road, and to conclude with an examination of the reforms which we should undertake and the crisis in travel and the use of the Road which has led to that duty.