CHAPTER VIII

THE “BLINDNESS” OF ENGLISH ROADS

The Two Causes Governing the Development of English Roads—Waterways and Domestic Peace: The Relation of the English Road to Military Strategy.

i

Of many of the features of the English Road we can determine the origins at once, for they are of common knowledge. The “blindness” of the English Road is due to the enclosures and the consequent increase in hedges since the seventeenth century, coupled, as I have said, with the dying out of “champion” or “co-operative” open-field farming. It is in part due, also, to that which has also been alluded to and has affected the English Road in all its aspects (surface, variation of gauge and gradient, tortuousness, etc.), the government of the squires following on the defeat of the monarchy nearly three hundred years ago. I shall touch on this again when I come to the history of the English Road.

But, apart from these obvious and well-known causes, two causes much less familiar—and yet of the first importance—two causes peculiar to this island in all Europe, have governed its development: waterways and domestic peace.

The English road system has been so powerfully affected by these two agencies—the one physical, the other political—as to have become wholly differentiated by them from the systems of the Western Continent. The natural feature then is the omnipresence of waterways throughout the island; and the political feature is domestic peace—that is the absence since the modern development of roads began (during the last 250 years) of strategical necessities on a large scale.

ii

I will take these two things in their order.

The way in which the whole history of England has been modified by the presence of water is a topographical point of capital importance to the understanding of the national life. There is no other large island in the world which has rivers in anything like the same proportion as we have, either in number or in disposition. Most of the large islands have no navigable rivers at all. Sicily has none, Iceland has none, nor Crete, nor Cyprus, nor Sardinia, nor Corsica. Not only have we a host of navigable rivers, but they are so disposed that they penetrate the very heart of the country. The Trent, for instance, is the most arresting thing upon the map. It looks almost as though it had been specially designed to make the inmost heart of England penetrable to commerce and travel in the east. The Thames, in the same way, goes right into the heart of southern central England; and even the Severn, the rapidity of which has militated against its modern use, had a considerable use in the past and was an artery in the Middle Ages, even for upward traffic, to the neighbourhood of Wenlock Edge.

The great rivers alone, however, do not account for the most of this character. It is the mass of small but navigable streams, both tributary to the main systems and isolated along the coast, which have so profoundly affected our history. If you take one of those outline maps of England with the waterways only marked, such as are sold for use in schools, and plot out the highest point upon a stream to which a fairly loaded boat can penetrate, you will be astonished to find how small a central area is left out. One might say that the whole of England, outside the hill country of the Pennines, the Lakes, and the border, is so penetrated by water carriage that if there were no roads at all its life could, under primitive conditions, be carried on by waterways alone.

Now this universal presence of waterways, which meant every opportunity for internal traffic and also for approach from outside the island, has had two effects upon the Road. First, it has made for diversion—that is, for the modification of the English Road from a direct to an indirect and sinuous line. Secondly, it has interrupted what would otherwise be main lines of travel in the necessity under which men found themselves of turning aside for the lowest bridge upon each stream.

As to the first of these points, it will at once be observed that unless you have some strong compelling motive for driving a simple straight line you will, in a country of many rivers, avoid such a scheme and seek for the cheapest crossing of each water. You must seek a ford, or narrow, or a place with specially hard banks, and not merely take haphazard that part of the stream which lies on your direct line, and seeing that such numerous waterways involve also long numerous flats along the streams, valley floors subject to flood or formed of boggy soil, the tendency to diversion in a road system under such conditions is intensified by the marshes which abound in a country so watered.

If you look at the Roman road system you will see how, for the considerations which I will deal with later, it usually; if not always, neglects special opportunities and takes the water as it comes, preferring an expensive straight line to a cheaper winding line; but everything done since the Roman road system has been affected by the perpetual consideration of the easiest river crossings inland, while the same influence has deflected the road round the greater estuaries and ports.

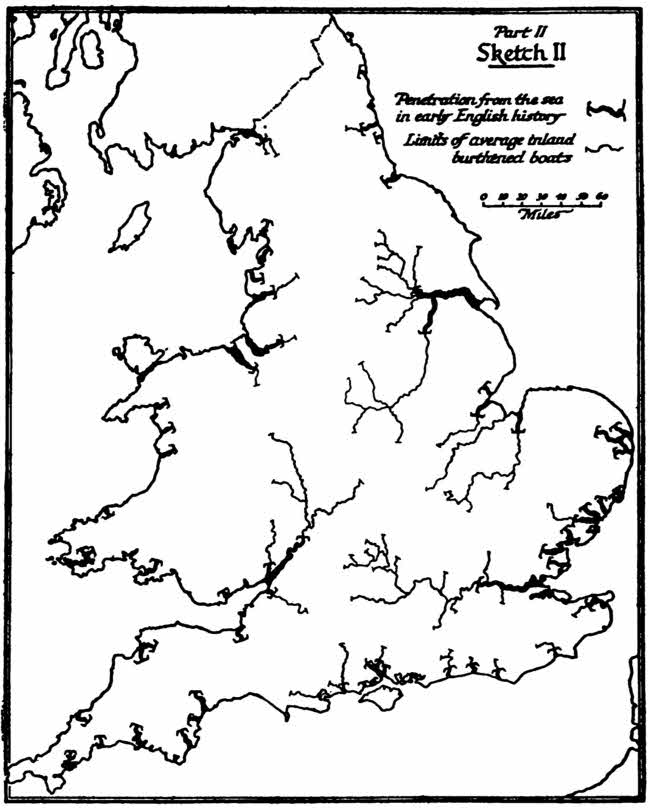

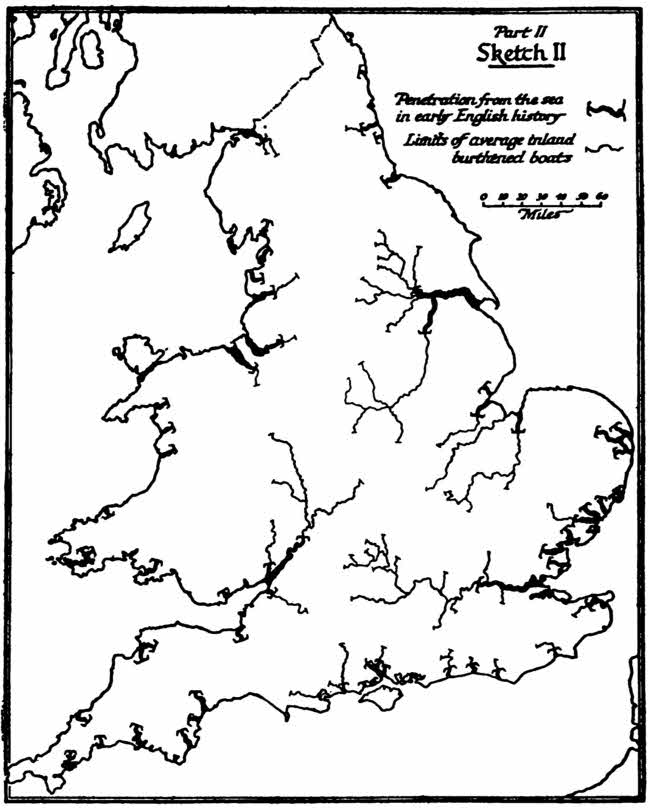

Part II, Sketch II

The lowest bridge over a river is a point of transformation. It stops traffic from the sea going any higher. But to carry on your journey from the sea as far as possible is obviously an economic advantage, especially in early days of expensive and slow road traffic. Therefore a nation dealing with the sea and largely living through sea-trade casts its first bridge as far up stream as possible, and that is exactly what you find upon all the rivers of England for centuries. Even to this day the tendency to build bridges lower down than the old first bridge is checked, in spite of the very strong motive we have in the development of the railway system. Take a map (Sketch II), and look round the coast and see how true this is.

The lowest old bridge of the Tyne was at Newcastle; of the Trent, I believe, at Gainsborough; of the Thames, of course, right up inland at London; of the Stour, at Canterbury; of the Sussex Ouse, at Lewes; of the Arun, at Arundel; of the Exe, at Exeter. The deep arms of Plymouth Sound were unbridged until the railway came; so Fowey river and the Fal, unbridged to this day; the Severn is not bridged at all till Gloucester, nor was the Dee till Chester.

Now this had the effect everywhere of checking a direct road system and deflecting the ways everywhere to suit the convenience of the ports. And there again we find, for reasons which will be given in a moment, the Roman roads directly crossing estuaries, but every subsequent road system going round them. Take two examples. The Roman road to the north, which runs all along the ridge of Lincolnshire, strikes the Humber where that stream is from 2000 to 3000 yards wide, crosses by a ferry, and continues on the far side.

The Roman road system of Kent did the same thing over the Wansum when that stream was—as Rice Holmes has proved—a broad estuary 3000 yards across, with Richborough as an island in its midst. The Roman road from Dover and the one from Canterbury met at a point opposite Richborough, whence a ferry took people across to Richborough.

Again, the Roman road to the lead mines of the Mendips ends at the wide mouth of the Severn, and is carried on again on the far Welsh side. But every road system since has gone right round by Gloucester, and the inconvenient effects of this, as road travel develops and water carriage declines, are very noticeable to-day. In all that southern coast of Devon between Lyme Regis and the Exe, if you want to get round to the maritime south-western bulge of the county you must make an elbow through Exeter. Similarly the Sussex coast, now so crowded, has only been linked up quite recently by bridges: the one at Shoreham was built within living memory, the swing bridge at Littlehampton is an affair of the last few years, as also the swing bridge at Newhaven of this generation. For 1500 years no one could proceed along that coast continuously from, say, Portsmouth by Littlehampton, Shoreham, Seaford (later Newhaven), Hastings, Rye, without turning inland to cross at Arundel, at Bramber, at Lewes, at Robertsbridge. One of the subsidiary effects of this interruption was the comparative ease with which the coast could be attacked from the sea, for the difficulty of rapid concentration upon any one point, in the lack of lateral communication, handicapped the defending force by land. All through mediaeval history the Sussex coast was raided from the sea. So much for the effect of waterways, the main physical cause of diversion in the English Road.

iii

The political cause of diversion has been, as I say, the negative effect of an absence of grand strategy in modern times. There has been no grand strategy in this country since the Romans, because there has been no fighting of a highly-organized type within the island during the whole of its post-Roman history. There was a great deal of barbaric fighting in the Dark Ages, and a great deal of feudal fighting in the Middle Ages. Even in the beginning of modern organized warfare you had (on a very small scale, it is true) the civil wars.

But since then—that is, during the whole of the period in which modern road systems have developed (1660 onwards)—there has been no necessity for strategical considerations to affect the English road system at all, and, therefore, no political force strong enough to compel direct roads was present in opposition to the strong economic motive for diversion.

The result is an anomaly that might well become serious if we had to depend upon our road system under the threat of invasion. Look, for instance, at the two great handicaps, the Humber and the Thames. A force standing up to meet a threatened landing which might be directed against Kent or against East Anglia would be divided into two sections, deprived of road communication save round through London. During the War a temporary bridge was thrown across the Thames (in the neighbourhood of Tilbury, if I remember aright), but, of course, with a gate for traffic. In normal times you could not have such a thing. The water traffic is too great and too confused. But what you could have would be a tunnel, and though the necessity for it may never arise it is also true that should it arise we shall bitterly regret not having driven that tunnel. The same remark applies with even greater force to the Humber. An attempted landing on the north-east coast of England, threatening alternatively the Lincolnshire and Yorkshire coasts, would find the defending force cut in two, and were the strategics of this position to become acute we should regret the lack of a road tunnel under the Humber, just as we should regret the lack of a road tunnel under the Thames.

The third principal case, that of the Severn, is partially met by a railway tunnel—the Severn Tunnel, far below Gloucester. A road tunnel would hardly suggest itself here. There is not a sufficient “potential” for it on either side of the stream. But here again it might well happen that under the particular circumstances of war we should regret the absence of it.

This negative factor, the absence of a strategic “driving motive,” has also left the windings of the internal road system at the mercy of the easiest crossings of the rivers, and we see how different the thing would have been under a strategic scheme. Consider the Roman contrast. The Roman roads of Britain were principally military. The whole scheme of Roman government was military, and the life of all that civilization was founded on the army. With the marching of men rapidly and easily from place to place as the main motive of the builders, the roads follow those great straight lines which, while duly seeking a formula of minimum effort, never sacrificed to it directness of plan. As we have seen, even at the great estuaries Roman engineers preferred a supplementary ferry to continue the road rather than deflecting it round by the first bridge.

In this connection, however—that of estuaries—there is one case which is puzzling: the case of the Thames. An explanation can, I think, be found, though at first it looks anomalous. The Romans dealt with the estuary of the Severn and of the Humber by ferries; they dealt by long bridges with lesser obstacles. In the same fashion they carried the north road over the Trent by a direct line without deflection for a special crossing. They carried it across the Tyne at deep water approached steeply. They carried it across the Thames at Staines with a sole regard to the direction of their road and without considering special opportunities of crossing. They did the same at Dorchester; and instances could be multiplied all over the kingdom. But apparently they did not attempt to attack the Thames estuary.

When one considers the nature of the early fighting during the first conquest of the island by the Romans this is astonishing. All the campaigns began in Kent, and the more serious of them were carried on into East Anglia. The great rising under Nero was an East Anglian rising, and the Roman armies beaten there had to be rapidly reinforced from Kent. For 400 years troops poured in, under any special emergency, from Dover, came up through Kent, and any immediate necessity of reaching a point east of London necessitated a détour by London Bridge: though time might be vital, the deflection was suffered.

Why did the Romans not solve the difficulty and establish at least a ferry across the lower Thames? Of course, they may have done so. You can never argue from the absence of traces to-day that a Roman road did not exist, for it is astonishing how thoroughly time eliminates such things. There are whole great towns like Aquilea and Hippo of which not even the foundations remain to-day. Even in England, where Roman survival is most marked, two towns, Silchester and Uriconium, have gone save for a few ruins; and there are great stretches of Roman road in every country of Western Europe which have mysteriously and wholly disappeared without leaving a trace of the tremendous work undertaken to build them; for instance, the miles after Epsom racecourse. Still, it does look as though no direct Roman line connected Canterbury, for instance, with Colchester. And I say again, how are we to account for it?

I think the explanation lies in the disposition of the marsh lands on the lower Thames. If you take the map of the Thames below the Isle of Dogs and mark upon it all that must have been primeval marsh (including much that is still marsh) you will see that wherever hard land is found upon one bank it is faced by extensive swamp upon the other. There was no good position for a permanent crossing even by ferry, and in the whole military history of England we only know one doubtful case in which a junction was effected from south to north, which is in the pursuit of the defeated British army by the Romans in A.D. 43 under Aulus Plautius. If, as is probable (though not certain), that battle took place at Rochester, then the pursuit was carried on by a direct crossing of the lower Thames; but with that exception I can call to mind no military action in the whole of our history where the lower Thames did not prove a permanent obstacle.

It is an amusing speculation to think what would have happened to the road system of England if strategic necessity had appeared again during the modern period. The thing is purely hypothetical, but I might make a few suggestions.

In the first place, we should certainly have had a road linking up the southern coast; next, we should certainly have had some form of continuous traffic over the lower Severn and the lower Thames and the Humber; next, without doubt, there would have been pierced a broad, continuous, and fairly direct road from the plain of Yorkshire to the plain of Lancashire across the Pennines; next, we should have had, of course, a broadening of all the ways leading to the main ports. That would have been essential, and particularly to the ports of the Straits of Dover. But, as I have said, the whole thing is a dream, because not that strategic motive, but now a purely economic motive is compelling us to revise our system.

iv

Apart from these two main causes of waterways, and of the absence of strategic necessity causing the diversion of the English Road, and apart from all other causes of local government which have led to such extraordinary diversity, lack of regular gradient, lack of regular gauge, etc. (as distinguished from the road system under the monarchical and centralized governments of the Continent, and especially of France), we have certain other elements which have stamped the English Road with its particular character.

They may be briefly recapitulated without developing any one of them. We shall meet most of them again in the historical sketch of the English Road.

There is the dampness of the climate; there is the extraordinary diversity of soil within a comparatively small area, so that road-making material continually differs within a few miles—for England is, of all European countries, that in which there is crowded upon a small space the greatest, sharpest, and most frequent diversity of soil and landscape; there is the increasing density of population in modern times, which has had a profound effect upon our road system. There is the political factor of Parliament; for since the defeat of the monarchy in the seventeenth century no direct order could be immediately obeyed until there quite recently grew up the new powers of administration. Between, say, 1660 and the Premiership of the late Lord Salisbury we may say that any important public right, including the making of a new way and expropriation of land for it, fell under no immediate authority but had to be referred to the lengthy and expensive process of a Committee, called Parliamentary, through which the oligarchy of Great Britain worked.

All these things have affected the development of the English Road, but most of all, let it always be remembered, these two main causes, which have been, in my opinion, far too little recognized—the waterways, peculiar to this island, and the absence of modern strategic necessity, also peculiar to this island.