CHAPTER XIII

WHEELED TRAFFIC AND THE MODERN ROAD

The Transition from the Horse to the Vehicle: The Distinctive Mark of the Later Seventeenth Century: The Turnpike System and the Making of the Modern English Road: The Underlying Idea of the Turnpike and its Effects for Good and Ill: Its Decline and the First Emergence of the General National System in 1810: Thomas Telford and His Work: The Movement Connected with the Name of Macadam: The Coming of the Locomotive and its Results on Canals and Roads.

i

The next great change came with the change in local government to which I have alluded. It gave us the first Acts of Parliament, taking the place of the old customary upkeep of the roads, but acting, oddly enough, at a period during which the road was declining everywhere. Even the civil wars did little to amend what had become a badly decayed scheme of communication.

One of the reasons for this was that the great arm of the civil wars was the cavalry, and cavalry is not tied to roads as infantry is. Another and better reason was the comparatively small numbers engaged.

The civil wars loom large in our political history because they marked the destruction of the monarchy and the beginning of aristocratic government, but in military history they are no very great affair: a sort of local epilogue to the Thirty Years’ War and the great religious struggle upon the Continent.

What did make a difference was the sudden increase of wheeled traffic with the end of the seventeenth century.

There has been a great deal of exaggeration in this matter. Sundry historians have written as though wheeled traffic were unknown until very modern times. That, of course, is nonsense. But the distinctive mark of the later seventeenth century and early eighteenth was the gradual substitution of ordinary passenger traffic by wheel instead of on horseback. The public vehicle comes in much at the same time as the private vehicle, developed by the new great landlord class for their convenience in their country rounds. As has been the case with the internal combustion engine in our own time, the instrument preceded the change in the road. As wheeled traffic for passengers becomes more common you get increasing complaints on the condition of the roads and increasing motive for improving them, and out of that grows the turnpike system, which, with its later development, has carried us on to the present day.

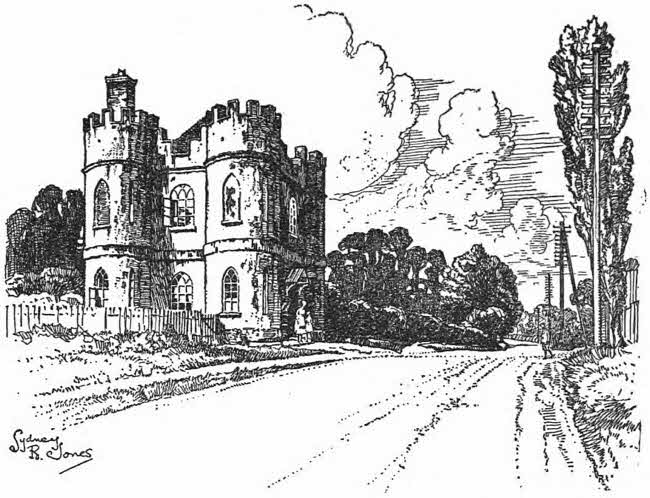

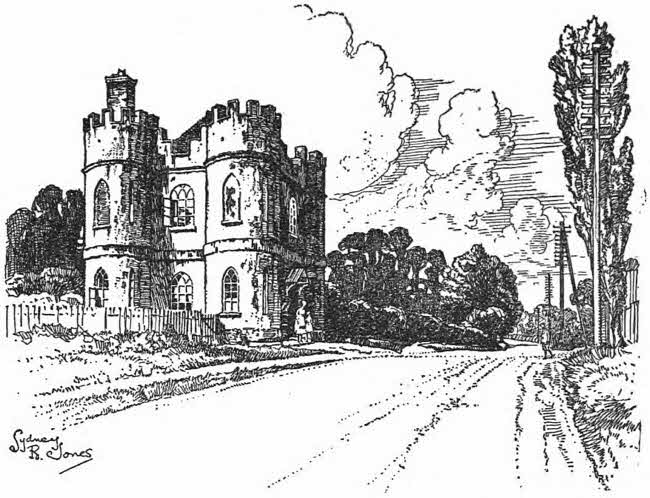

TOLL HOUSE ON THE BATH ROAD

ii

THE TURNPIKE SYSTEM, by a process which originated in small beginnings and ended with a revolution in general communications, made the modern English Road.

It sprang from that character in the economic society of Britain (closely connected with the new aristocratic government of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) whereby, in the destruction of the monarchy, individual action became supreme.

The same force which had forbidden great national roads to rise, to wit, the absence of a central all-powerful authority (such as was the French monarchy just over the Channel, with its great roads planned and constructed throughout the whole realm on one model)—which had maintained local diversity and local usage and kept back the proper development of the road—made for a change which should be due to private enterprise.

We all know of what value this individualist and aristocratic economic system was to the expansion of English trade overseas, and how it is at the foundation of what is to-day called “the Empire.” In domestic affairs it meant, of course, the sacrifice of the interests of the community to a comparatively small wealthy class, but that did not prevent this wealthy class from acting very efficiently under the opportunity for gain within its own sphere. The mass of Englishmen became, and have remained, impoverished, but the total wealth of the country and its population have vastly increased.

The idea of the turnpike was to give a small body of capitalists the right to exploit certain sections of road. They would improve the surface and broaden the gauge where necessary, etc., but they would put up gates where they could charge for the passage of all and sundry and thus earn the interest upon their money. They had also powers to borrow. They had certain powers for using the public rates, etc., and in general, through this system, the roads of the country were more and more given over to what we call to-day capitalist exploitation: for although very often the sections of road thus exploited were short they formed an interruption to general travel.

Popular resentment against such an innovation was, of course, bitter, especially when it extended to large areas. There were periods of riot in which the toll-gates were destroyed, and there was something like a little civil war in the matter in South Wales, but the interests of the wealthier class were supreme, the populace was suppressed, and the system continued. It also vastly extended.

While it had the social disadvantages just mentioned, it had the economic advantage of creating bit by bit longer and longer sections of really good road up and down the country. To the turnpike system we owe that development of the English roads which made English coaching and gave us, in the generation before and during the Napoleonic wars, on the whole, the best system of local communications in Europe, though we still grievously lacked continuous national communications between distant centres.

iii

The date to which must be referred the great change in this respect—the date from which we must count the growth of general national communications continuous throughout the island—is the year 1810. The turnpike system did indeed die slowly and only much later. It lingered on to well within living memory, and those who are curious to watch the rise and decay of institutions may even argue that some relics of it remain among us still. But in practice 1810 is the date of the first experimental change which was ultimately to produce the road system of to-day.

If we consider the use and character of the Road, its texture and appearance, its effect upon the landscape, its connection with society as distinct from the legislation connected with it, 1810 is much more of a pivotal date than such dates as 1555 or 1822, which mark the political changes in the statutory powers of dealing with roads. Already stage coaches driven from the box, and every year increasing the rate of travel, had been upon the road for a generation—for twenty-six years; and already great lengths of turnpike trust roads had come to a sufficient excellence of surface to permit travel at an average rate over those branches of ten miles an hour. But, as I have said, there was not as yet one continuous piece of road designed to connect two important termini, of equal value throughout, and ordered in all its length towards that one end of making equable and rapid transit possible between the two extremities. That is the point. The thing had not existed in this island (save in the “four Regal Ways”) since the breakdown of the Roman central government in the fifth century.

What happened in 1810, and what makes it such a memorable date, is the appointment, under the pressure of the Postmaster-General, of a stonemason who had risen to the practice of road engineering—Thomas Telford—to the overlooking of the Holyhead Road.

The initiative came from the Post Office Department: the administrative and engineering genius came from Telford. Incidentally, we should remark, as one of the innumerable examples of unforeseen and exceedingly important side developments in history, the fact that this great revolution in British roads ultimately derived from Pitt’s Act of Union with Ireland, which was already nine years old. It was the necessity of communication between London and Holyhead, and especially of postal communication, which did the business.

Telford had been in the employment for some years past of the Highland Roads Commission. He had therefore proved his capacity, and from it he was appointed to a Government position in the re-establishment of the Holyhead Road after the affair had been examined by a Parliamentary Committee in this year (1810). It was not only Telford’s skill, it was still more his energy and intense application to detail which wrought the change. His nominal masters were ten Commissioners and three Ministers at their head; his real chief was Parnell, later Lord Congleton. But it was Telford, by his ceaseless travelling and investigation and overlooking of everything, who pushed the thing through.

The whole distance to be reorganized was one of 194 miles. Of this the larger part, 109 miles, fell under seventeen English Trusts; the remaining 85 miles were under six Welsh Trusts, the latter with far less local traffic to provide them with income, and, it would seem, also of less general efficiency.

Telford’s task may be appreciated when we remember that the new policy gave him no direct statutory power to override trusts. Each one had to be argued with, bargained with, and persuaded. This at least was true of the English Trusts and the six Welsh Trusts. The Commissioners, or rather Telford and Parnell, despaired. The trusts controlled so very much the larger part of the trajectory that it was necessary in some way to dispose of them.

More than seven years passed before this could be done. But Parnell succeeded in persuading them, by industrious attendance before various meetings, to accept an Act of Parliament which cast them all into one body of fifteen, and they were, by statute, compelled to employ a professional civil engineer, who was, of course, Telford. The 85 remaining miles were taken over, scientifically divided into sections under assistant surveyors and foremen below them, and by 1830, after the labour of twenty years, the whole thing was done. A suspension bridge had been thrown over the Menai Straits, Holyhead Harbour had been improved. These, with the reconstruction of the road, had drawn from Parliament grants of three-quarters of a million. From that moment there existed at least one complete road in Britain, uniting two definite termini and everywhere making possible the rapid travel at the time. The tolls were, of course, maintained. Their cost was increased by one-half. The anomalies, complexities, and corruptions involved in the system were no more done away with on the Holyhead Road than on any other, except in so far as a closer supervision helped to alleviate things and in so far as amalgamation of trusts also helped. But, at any rate, there was at least one continuous and excellent road from the capital to a distant port, and we have the date 1830 for the completion of the great task which was begun in 1810.

iv

Contemporary with this first great complete model of a road in England went the movement connected with the name of Macadam. It was far less of a revolution than has since been represented. The Continent had made experiments similar to those of Macadam long before him, and what he effected over here was no more than an improvement, for it was not wholly novel.

The real point of Macadam in our road history is his intense devotion to his task. He was one of those men who, having seen clearly a principle which others have also seen, and which, indeed, should be obvious, so emphasizes it and represents it that he brings it into practice where other men would have abandoned it. The obvious principle which Macadam grasped and reiterated to weariness was the principle that perpetual legislation and experiment in the type of vehicle best suited to a road was of less importance than the surface and weight-carrying capacity of the Road. Get the best road you can first, and after that discuss the traffic along it. In certain technical details posterity has criticized it—in its insufficient allowance of foundation, for instance; in its postulate that a well-drained natural surface was sufficient to bear anything in the way of road traction. Such criticism can only be conducted by experts, but it is certainly true that Macadam transformed the surface of the English Road, not perhaps by any special or novel conception of his own either in the material or in the sizes of that material, but rather in the unique insistence with which he carried on his whole task.

Just as the Post Office had been the Government department for using Telford, so the Board of Works was the Government department backing Macadam.

These two men between them, and these two departments between them, had remade the English Road, and the system was fairly launched towards such a change as would perhaps have given us a completely transformed road system, the value of which we should have appreciated when the new traffic of the internal combustion engine presented us with the problems of the present day.

For instance, Telford himself had suggested—and there was nearly achieved—a reformed stretch of the Great North Road between Peterborough and York on a straight line, avoiding the windings of the old trace, and twenty miles shorter: worthy to rank in every way with the great roads of the Continent. This, had it been realized, might well have proved only the first of a great number of similar constructions, until we should have had all the great centres of England united in the same fashion and a habit of broad, straight, and excellent roads established. Unfortunately, a great historical accident intervened to sidetrack the whole business. It was an example of the way in which the advantages of spontaneity and inventiveness, making normally for the benefit of the community as a whole, will, if there is no central direction, do incidental hurt which has later to be repaired, if at all, at great expense of energy. The reason we have to-day the innumerable narrow winding roads of England, the lack of any general system, the absence of any system of good roads from London to the ports (to this day half the exits from London are blocked by absurd “bottle necks,” the most notorious of which, of course, is that on the West road, which is now at last being remedied), is that the English genius produced the locomotive.

v

Stephenson’s great revolution was begun in 1829. The great Holyhead Road was completed in 1830. The coincidence of dates is significant. England developed immediately an immense system of railways. Not only was she twenty years ahead of the rest of the world in the business, but she alone, for a long time, could produce railways. The railways on the Continent had to be built often by English engineers and always upon an English model. The transformation which this effected in the national life was so rapid that it warped judgment. Men began to talk as though the road would fall out of use. It was the same sort of exaggeration as led people about ten years ago to tell us that shortly horses would no longer be seen in the streets of London or even on the country roads.

The introduction of the railway had two deplorable effects upon the economic life of England, each of which was grave, and one of which we must, if we can, immediately remedy on peril of decline. Neither of them can be remedied save at a new expense of energy: (1) It killed the canals, (2) It killed all the schemes for widening, straightening, and rebuilding the national road system; while upon the Continent, and especially in France, the great broad, straight roads of the eighteenth century formed the model continuously applied, so that the most recent examples to-day are in the same tradition as those of two hundred years ago and yet amply fulfil their function. Here the whole story of our roads from the middle and the end of the nineteenth century and on to the beginning of this century is the story of improving the surface while keeping to the old winding and narrowness. Here and there we have had extensions of space which create really new roads in the neighbourhood of towns, especially as exits from towns, but nowhere as yet have we a complete scheme for the remodelling of a road in the fashion whereby, a century ago, the great Holyhead Road was remodelled.