CHAPTER XII

THE DARK AGES

The Decline of the Roman Road: The Period at its Occurrence: Gaps: Roman Roads which Fell into Disuse: The Relationship of the Modern to the Roman System: Watling Street: Stane Street: The Short Cut Between Penkridge and Chester: Peddars Way: The coming of the New Civilization in the Twelfth Century.

i

The next phase in the development of the English Road is the very gradual breakdown of the great Roman ways. The Dark Ages—that is, the 500 or 600 years between the fifth and the tenth or eleventh centuries—formed the period during which this process took place.

The Roman Road in England suffered the fate of all our ancient civilization. It very slowly declined and coarsened, but it remained the one necessary means of communication. We have no dates and no contemporary record after the fourth century for Britain, but we have the analogy of Northern France, in which we know that the upkeep and repair of the great Roman roads continued until well into the seventh century, and we have the evidence of the Roman roads as they now stand before us, with the result of their very gradual and only partial breakdown in a use of centuries. We have also the fact that much the most of the great battles took place on or near the Roman roads until the twelfth century, that most of the new great monastic and other houses were built near them, or on them, and that the ports most commonly used in the Dark Ages were nearly always ports with a Roman road serving them. We can thereby roughly judge (although we have no direct evidence) what happened to the system.

In the first place, the Roman Road was so solidly built that centuries of neglect did not entirely destroy its usefulness. Sections of each road disappeared: some from causes which are easily explicable, some under the most obscure conditions the causes of which it seems impossible to discover. Every great Roman road in Europe, and even those in Britain (which are better preserved than those in the most part of the Continent) shows these gaps. Sometimes a whole great section of road will almost entirely disappear—more often it is a stretch of a few miles. Thus the whole of the short cut through Penkridge to Chester, which certainly existed and some elements of which can be reconstituted, has disappeared; so that most maps of Roman Britain erroneously mark the connection between London and Chester as going round by Shrewsbury. As an example of a short part utterly disappearing, one can take any one out of hundreds; the best example near London (typical of many others) is the gap in the Roman road between the Epsom racecourse and Merton. The road is evident as a clearly marked high embankment above the steep rise at Juniper Hill near the Dorking road to within a mile of Epsom racecourse. Then it suddenly ceases. There is no change in the soil. It is on chalk before and after its disappearance; and yet, just here, at about a mile from Epsom racecourse, it completely and totally disappears. There is no trace even of its foundation left from thence onwards northwards until you get to the site at Merton (which was state land and almost certainly the last camp and halting-place on the road before London).

How the road crossed the marshes of the Wandle we can only conjecture, as we can only conjecture where it lay exactly between Epsom and those marshes. Why it should disappear in the marshes is evident enough. The causeway sank in. Why it should disappear under the plough to the south of the marshes, as Roman roads nearly always do on arable land, can also be explained. But why it should wholly disappear on the last mile or two of chalk is inexplicable. One theory put forward is that in the great wars of the Dark Ages portions of the road were deliberately destroyed to impede the progress of an enemy, just as a railway may be destroyed in modern warfare. But this theory will hardly hold water. The gaps that have disappeared thus, often come just where you have the best soil for marching independently of artifice, and where, therefore, an interruption of them would least incommode an advance. For instance, they are perpetually found on high chalk; and, further, the disappearance is hardly ever connected with a defensive position.

From the point of view of the development of the English road system much the most interesting point in the fate which befell the Roman roads is to be found at the crossings of rivers, especially of rivers which have marshy banks or flow through wood or sodden valleys. The neglected Roman embankment across the marsh fell out of use in the Dark Ages. Probably the bridge first broke down, and the barbarous time had not the energy or skill to repair it; then the mere process of time caused the swallowing up of the Roman viaduct, unrelieved by repair, in all marshy land. It is difficult to affirm a negative, but I can recall not one example of a long Roman viaduct still wholly in use across such an approach to water.

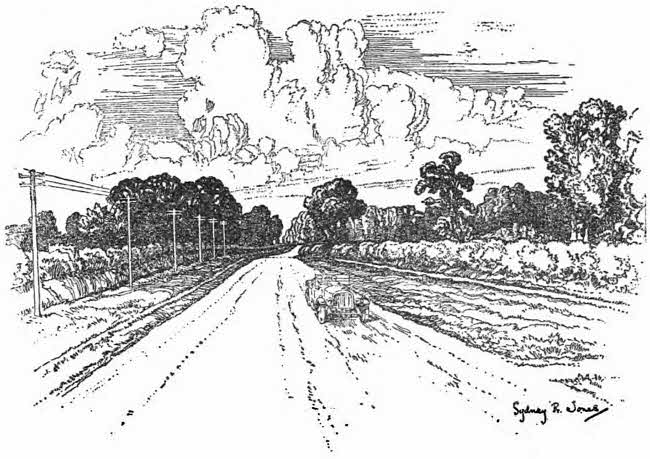

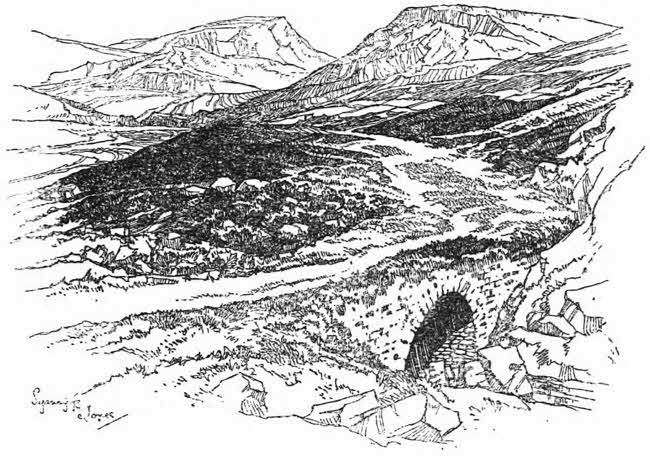

A DERELICT ROAD

SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS

What happened, then, in these sections was this. The bridge and the viaduct disappeared in the Dark Ages—that is, some time between the fourth and the eleventh centuries. Sometimes this gap led to the complete isolation of the district immediately concerned. The best example I know of this is the breakdown of the crossing of the Arun at Romans Wood, in the county of Sussex. There the Roman road was a hard causeway over very thick clay land, quite impassable for armies in winter, and rapidly overgrown by oak scrub and thorn when neglected. The result of the breaking down of the Roman bridge at the “Romans Wood” crossing was to isolate West Sussex. There was no other way from the north, for the clay and thorn scrub rapidly arose and obliterated the road. It was in use as far south from London as Ockley; but the breakdown of the bridge at Alfoldean broke the continuity further on, and that, I believe, is one of the reasons why Sussex was so isolated as only to be converted to the Christian religion a hundred years later than the rest of the country.

But to return to the behaviour of the Roman Road in the marshy approaches of a river. I say that the embankment having been swallowed up and the bridge broken, the men of the Dark Ages had to find for themselves some new way of crossing, and it is interesting to note that they here fell back upon the primitive methods common before Roman civilization came. They abandoned the straight line and picked their way by the driest bits they could find, so that the new crossing of the marshy district grew up sinuous and haphazard. Later, when the new road system developed with the Middle Ages, this new road was often straightened and a new bridge thrown across the river upon its line; but, save for a very few exceptions, the Roman approach had disappeared.

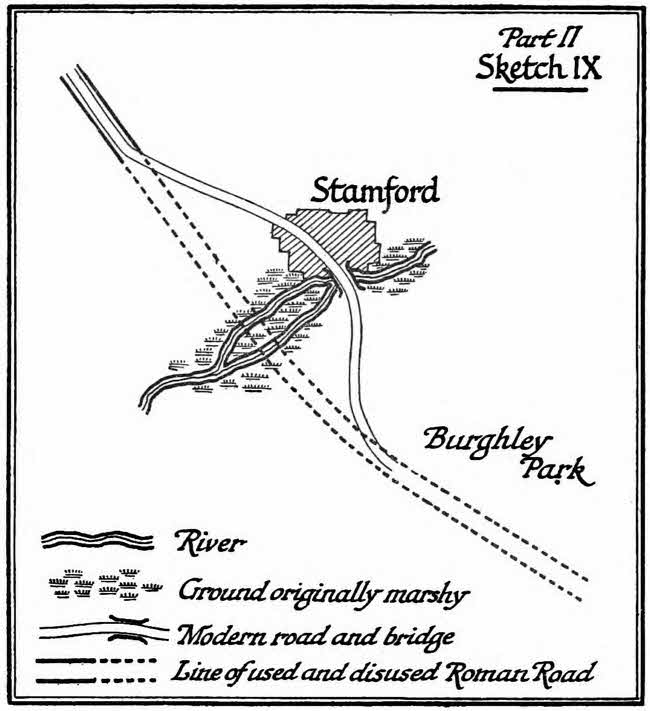

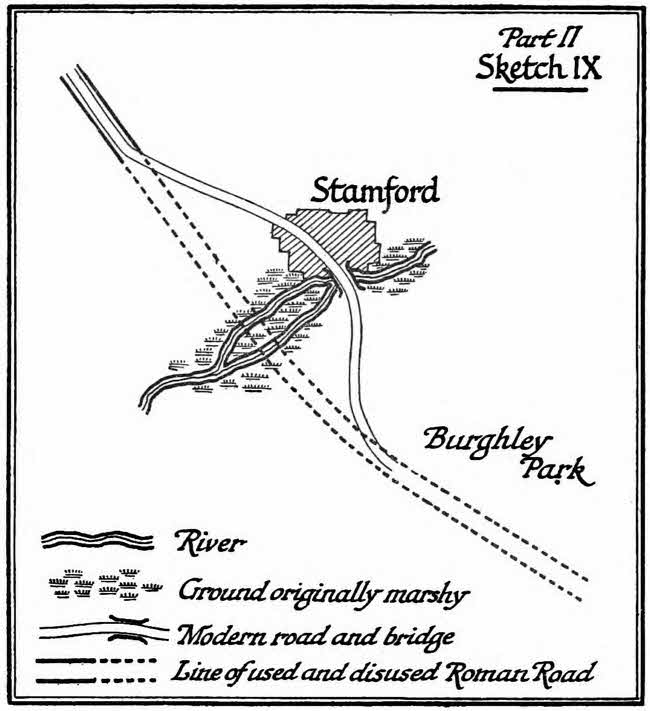

There are scores of examples of this up and down the country. The most prominent usually bear such names as Stamford, Stanford, Stafford, Stratford, Stretford, etc., all of which come either from the word “street” or the word “stone,” coupled with the word “ford.” They thus signify that in the valleys of the river the “going” or passage had been hardened artificially with stone derived from Roman work. A very good example of the way in which the newer track replaced the older one is to be found at Stamford, in Northamptonshire. The accompanying sketch shows the trace of the Roman road from its leaving Burghley Park to the old crossing of the river and beyond. There are still broken traces of the old embankment on the north side of the stream, but it is clear that this straight line across the marsh broke down, that a new way was picked out and slowly hardened, and a new bridge built to suit it. What the men of the Dark Ages did here was to keep to the drier patches to the east where a ford crossed the river, and then curve round again westward, again to join the road on the heights north of the river. This new passage took over the name of the “Stone” ford, where the old road had crossed. A bridge was thrown in due time across the new ford, and the town shifted towards the new bridge and acquired its new name from the crossing.

Part II, Sketch IX

One form of the Roman Road, and one only—a very rare form—never disappears: it is the cutting through hard sand. Here and there in England—I know not how often, but I have myself found few traces of them; I should doubt if there were much more than a dozen—you get a clear cutting upon a Roman road serving no modern or useful purpose, and almost certainly dating from the construction of the way. There is the trace of the one at Ashurst, near my home—that with which I am most familiar and which I have measured most carefully. If the cutting be made in dry sandy soil of fair consistency and hardness, it can remain almost indefinitely with an unmistakable outline. There may naturally have been many other cuttings originally in softer or more yielding soils which have got filled up, but the only ones I know are through sand, which soil also tends to form those sharp ridges through which a cutting might suggest itself as more economical than a too steep gradient.

ii

The Roman Road not only disappears through causes which I have called inexplicable and under the obvious influence of marsh or of cultivation, it also fell into disuse, even where it did not disappear, for reasons both explicable and inexplicable. There are cases where the falling into disuse is frankly not to be explained, though these I have found mainly upon the Continent. For instance, in the road from Rheims to Chalons you have the Roman road running almost parallel to the later road, the later trace having been made for no reason that we can discover—not serving any new towns or villages—a mere duplicate of the old way. But there are more cases where the disuse of a section of the Roman Road can clearly be explained by the need for visiting centres of population, production, and commerce. The Roman system for the serving of places off the main straight road was by side roads perpendicular to the main road. The relics of these you still see on many of the Continental roads—a direct perpendicular lane or avenue joining up the château and its dependencies or the neighbouring town with the main highway. When the Dark Ages came and the main roads degraded, the by-lanes and paths which had grown up as offshoots to them and which led to the estates and villages and towns and ports and quarries, etc., to one side or the other of the Road came to be used more frequently. The main travel between distant towns was less, the local travel grew more important in proportion. And as this development proceeded sections of the Roman Road tended to fall into disuse. The local roads would be maintained and the section of main road would be left unrepaired.

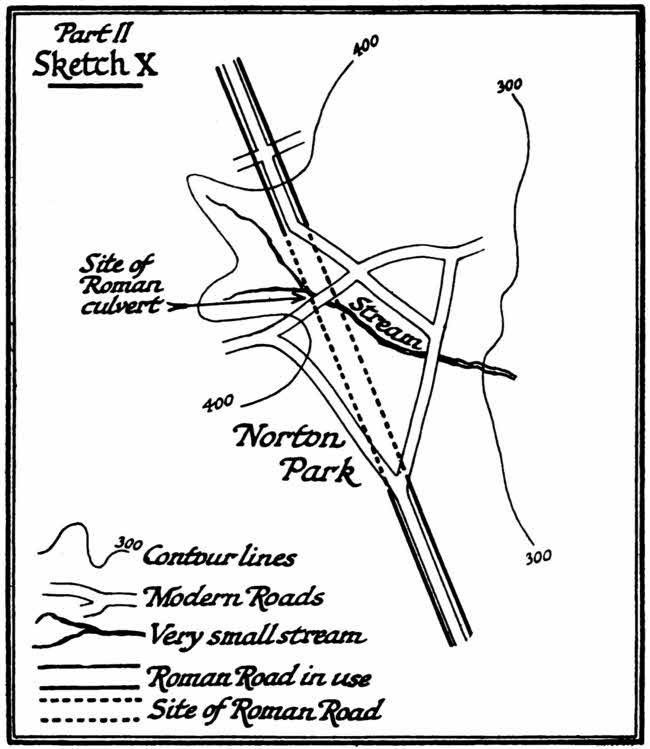

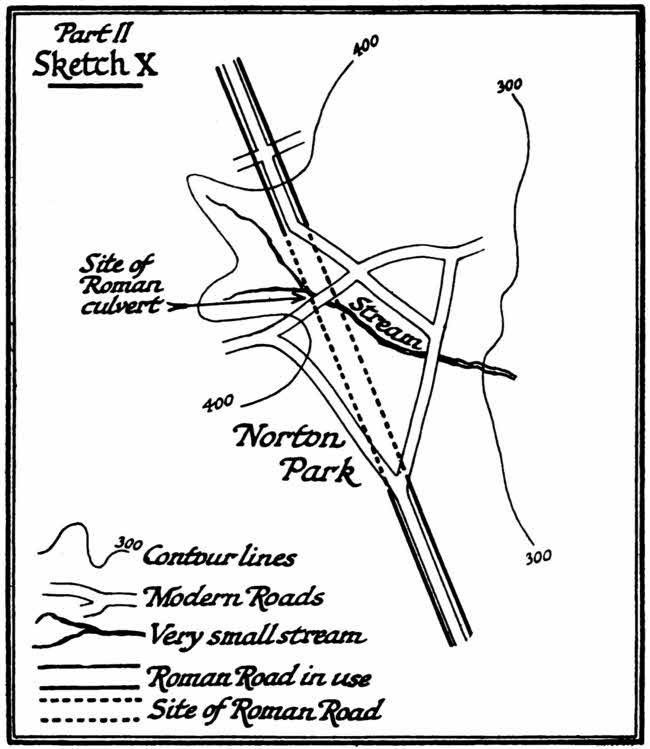

We have seen that the main cause of the breaking down of the Roman Road was marsh and the crossing of river valleys. Not only was this process true of natural marshes, especially at the sides of a river, it was true of a special case which is reproduced over and over again on the map of England, and for which I will take as a particular example a very fine case near Norton Park, in Northamptonshire.

Part II, Sketch X

Here the Watling Street, the great Roman road from London to the north-west, crossed the valley of an insignificant stream; there was no marsh originally, and there is none to-day. There was only a small running of water, over which a culvert was thrown. The stream ran under the main Roman embankment through this culvert. Now, when the Dark Ages came and the roads fell into disrepair the first things to go, naturally, were the culverts. They got blocked up. Once they got blocked up the water dammed up on the higher side and began to undermine the embankment. By the time this had made the road, though still standing, impassable, travel had found a new way, usually down the stream away from the mere thus formed. Further centuries and the recovery of civilization cleared the ground: the embankment either was washed away or swallowed up in the mere and its subsequent marsh, the stream resumed its original course, the dry ground reappeared, but the trace of the Roman road upon either side across the depression was lost for ever and there was substituted for it the modern road, making a curve out of the direct line and only recovering it again after the obstacle had been passed.

iii

The gradual decay of the Roman Road in the Dark Ages was not everywhere the same, and the consequence is that the remaining fragments of Roman roads are connected in different ways with the modern road system which gradually grew out of them.

There are four types—overlapping, of course—of the fate attaching to the Roman roads of this country. They are, as I have said, the root of all our road system. All English roads subsequent to the period of the Roman occupation have grown out of the great network laid down for ever by the Roman engineers. But the fortune which the original road suffered, the way in which a modern system developed from it, were not uniform. There were four divergent developments, which ran thus:

(1) The Roman Road is preserved as a basis of the modern road, and remains a main artery: of this the great example is the Watling Street, in the first few days’ marches north-west of London.

(2) The Roman Road remains clearly the basis of the system of local roads which developed from it, and, though disappearing in sections, is, upon the whole, preserved; of these the great example is the Stane Street road from Chichester to London.

(3) The Roman Road, having produced a system of local roads based upon it, has almost entirely disappeared and has left the local system alone to witness to its original importance, just as filigree work remains after you have melted away the core of wax upon which it was built. Examples of this are very difficult to discover, precisely because the original country has gone. But the process can be followed here and there by a careful examination, and I think that, upon the whole, the best example is that of the series of roads which grew up out of the short cut between Penkridge and Chester.

(4) The Roman Road remains, in some parts at least, but, its original purpose having been such that it was of no continual use in the Dark Ages, the local system of roads can only indirectly be referred to it. Of this the great example is the famous Peddars Way, running through East Anglia.

iv

(1) The preservation of the Watling Street as an example of a continuously used Roman road for several days’ march north-west of London is due to various causes.

In the first place, it was very little interrupted by marsh. It ran everywhere on dry land, and the main cause of breakdown—the swallowing up of a causeway after the destruction of its bridge—did not affect it. But this is the least of the causes which have preserved this piece of road.

Second, and more important, was the establishment along it of set stations which remained inhabited, and the chain of which was not interrupted by active warfare. Watling Street here presents very interesting evidence of what really happened during those early pirate raids which are generally, but erroneously, called the Anglo-Saxon Conquest. They did not so seriously disturb the life of the country as to break down this main artery of communication. It lies transverse to the raids, and yet it was maintained. And in this connection we must also note the continued importance of London.

Great Roman towns suffered, of course, from the pirate raids between (somewhat before) the year 500 and the year 600, as did all the rest of the island. They suffered not only from those raids of pirates across the North Sea, but also from the raids of pirates from Ireland, and also from the raids of Highlanders coming over the wall from the north. But though they suffered they kept their place in the national scheme. No province in the Roman Empire lost less of its town sites in the Dark Ages than did England. No part of Europe has so large a number of old towns based upon Roman foundations: and London was the chief of them all. London may have been disturbed by the raids—it probably was. There was probably a certain amount of looting from time to time, and a good deal of fighting outside its walls, but it always maintained its permanence, its character of being the economic centre of the island. It is particularly noticeable that every great Roman road out of London has remained intact, and Watling Street beyond others.

The third cause of survival was probably the excellence of the original construction, though here we must hesitate a little because we cannot but note that the Great North Road to York, which was quite as important and which was twin to the north-western road, has suffered very grievous modification indeed. But there can be no doubt that the construction of the Watling Street was very thorough, and that this expenditure of economic effort preserved it through the Dark Ages as much as anything did.

Oddly enough, what is in most cases the strongest motive of all for the preservation of a road was here entirely absent, and that is what I have called the “potential” between the two terminals. When there is a long and continued motive for joining up two terminal points the Road has a cause of survival superior to any other. There was, and remains to this day, an extremely strong “potential” of this kind between the ports serving the Channel straits, with their nucleus at Canterbury, and the economic capital inland at London. It therefore, as the Roman road between the one terminal and the other, remained permanent throughout the centuries, with the exception of the deflection towards the Thames which grew up in the Dark Ages to serve the landing places at Gravesend. But such a “potential” is entirely lacking for the north-western road communication—so far as we know—to go between London and Chester. The trade with Ireland ceased almost during the early Dark Ages. The north-western road led nowhere. If it was preserved, therefore, as it has been preserved, it must have been due to other causes which escape us. There it runs, however, still almost uninterruptedly used, from the Marble Arch in London to Oakengates in Shropshire, and in places still acts as part of the main artery leading from south-east to north-west.

v

(2) STANE STREET. The Stane Street (which I must be excused for quoting so continuously as I know it in great detail) is, I think, the leading example of a road still remaining for the most part and clearly showing how the later systems were built up upon a Roman backbone.

I will take the liberty of recapitulating here my argument, developed at greater length in my monograph on this Way. The original motive of the Stane Street was the connecting of the Chichester Harbours, and indirectly of Portsmouth Harbour, with London by a road which should overcome the difficulties of the Weald. The Weald is a mass of stiff clay, impassable to general traffic for six months of the year unless one uses artificial means. Left to itself it turns rapidly into a waste of oak and thorn scrub: save in the dry months, there is no going over it in its natural state for armies or bodies of wheeled vehicles. Its watercourses are numerous, muddy, difficult of approach, and soft at bottom. It produces nothing save in moments of high civilization, when it can be heavily capitalized by draining and penetrated by expensive artificial communications. The supply of good water is rare and capricious. The Weald was, therefore, the great obstacle between the south coast and the Thames. Because it was such an obstacle the Romans drove their first great road from the main harbour of Portsmouth to the capital round westward by Winchester, Silchester, and Staines; but they needed a supplementary road, for two reasons. First, they wanted a short cut to serve Portsmouth and the lesser inlets collectively called Chichester Harbours (Bosham appears to have been an official port throughout the Dark Ages); and, secondly, they wanted to be able to reach quickly for purposes of travel and commerce the very fertile sea plain of which Chichester is the capital. Therefore did they construct the most purely military and most direct of all the Roman roads in the island, the Stane Street. It ran from the east gate of Chichester in a direct line to the crossing of the Arun at Pulborough, with a camp at the end of this first day’s march to defend it; thence it made in another great straight limb for the shoulder of Leith Hill, with a camp at the second crossing of the upper Arun at Romans Wood; thence by a series of much shorter limbs to the third camp at Dorking; thence over the Mole at Burford Bridge and over the Epsom Downs past the racecourse to the fourth camp at Merton, and thence to London Bridge—a five-march stage.

In the Dark Ages the Weald became impassable again, the causeway on the Arun marshes broke down and was swallowed up. The bridge at Alfoldean broke down, and Sussex was isolated from the north.

Further, with the absence of any exit for direct and rapid communication between Chichester and London the meaning went out of the road between Dorking and Merton. Merton was close enough to London to give the road vitality again, and between this and London it was never lost. It runs to this day, and is the main line of tramways upon which people still travel from Streatham and Balham to the Borough. It is only deflected at the end by the intricacies of the Southwark streets.

Now, if you look at the present scheme of roads surrounding this original Roman core they look at first as though they had no connection with it, but when you examine them in detail the way in which they grew up out of the Roman road is clear. Every deflection can be accounted for, and the development of the local systems from the original continuous backbone becomes evident.

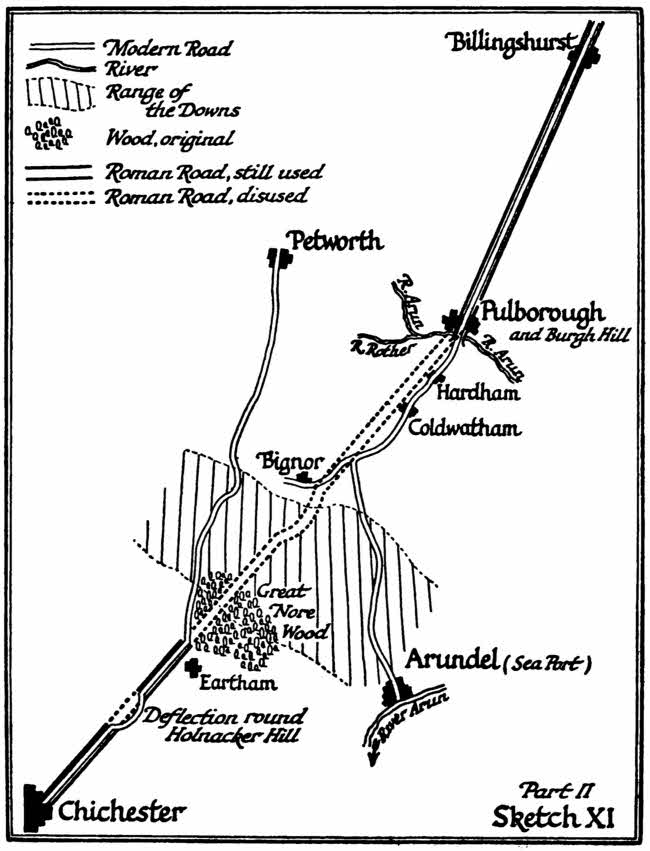

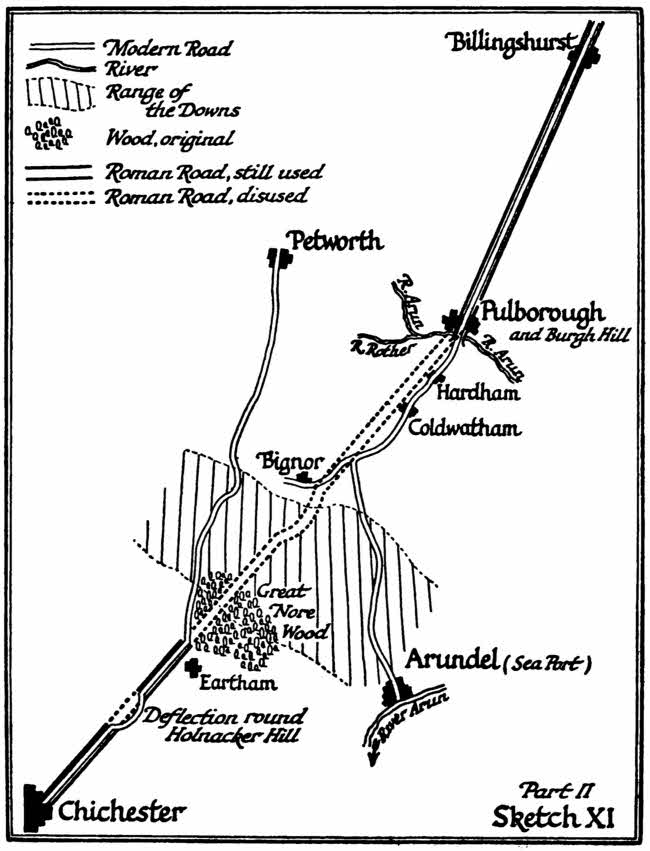

Part II, Sketch XI

First you have all Sussex south of Pulborough Marsh, and again south of Alfoldean Bridge, isolated.

What happens?

There remained no reason for using the Stane Street as a continuous line. It now led nowhere. When it meets with its first great obstacle going north, the woods near Eartham, it makes for the next centre of population—Petworth, where there was a fortified post going back to some very early time. The wood deflects the road towards Duncton Hill (I have quoted this example in my section on vegetation in the earlier part of this essay). Beyond Petworth it had little function, so this first ten miles of the Stane Street becomes the parent of the local Chichester-Petworth road which grew up out of it, leaving a gap where the woods intervened. Next you must note the local roads beyond this gap. Pulborough Bridge probably survived, but the causeway could not be kept up, or was ill kept up. In its original line, when it served the camp at Hardham, it ran over a wide part of the marsh. In the Dark Ages men picked their way over the narrowest part of the marsh and then followed the hard bank above the Arun-flooded levels, linking up the villages as far as Bignor. But there the use of the road ended. The “potential” was from Pulborough to the nearest seaport, which was then Arundel. And all that the Roman road did in this section was to throw out this bow or curve of lateral road eastward between Pulborough and Bignor, the line of main local travel being diverted from Bury over Arundel Hill and so seaward.

In the section north of Pulborough the Roman road still served a few scattered homesteads in the Dark Ages up to Billingshurst at least, but again it led nowhere because the bridge at Romans Wood was broken down and the high weald beyond was a mass of scrub growing on stiff clay. The road petered out and began again with harder going near Ockley. But it was not used over the shoulder of Leith Hill, because that trace subserved no local use and yet compelled the traveller to steep gradients. Travel was deflected round the base of the hills to Dorking, linking up the more populated part where the water springs were. This new trace, growing up obviously out of the Roman road, opens up to the eastward for a mile or two of the way until it joins up in the heart of Dorking itself, where the third camp was, out of which the town of Dorking has grown, and where in the churchyard the Roman road can still be traced passing through. From Dorking onwards one might have imagined that it would have survived all the way to London. Why did it not do so?

It was a matter of gradients and of centres of population. In the Dark Ages, when there was little necessity for making a direct line between Dorking and London—no continual marching of great Roman forces, no conveying of orders from a centralized government—men took the easier way. They abandoned the up-and-down of the spur of land lying immediately north of Dorking and went round by its base to save the trouble of the little climb. They used the Roman bridge (which apparently survived at Burford), but the very steep leap up on to the Epsom Downs they abandoned, especially as the further progress of the road over the chalk connected no centres of population. The way curled round by Michelham and Leatherhead and came round to Epsom—all places suitable for centres of population with low water levels and no heavy gradients in between. The Roman road on the high waterless chalk above was left abandoned.

What happened between Epsom and Merton has been already described. There is only one divergence in this section, which is where the road of the Dark Ages deflected somewhat to the left and was used to avoid the low wet ground below Clapham Common. For the rest it maintained its use.

ERMINE STREET NEAR ROYSTON

(3) The best example I know, as I have said, of a Roman road the evidences of which have nearly disappeared, but round which local roads have grown and which can still be identified as the core of these, is the short cut between Penkridge and Chester. It is very puzzling why the Roman road should here have disappeared. It is perhaps best to be explained by the continual fighting between the Eastern and the Western troops, which must have ravaged all that country between the first of the raids and the full conversion of England to civilization and the Christian religion which was the work of the seventh century.

But, whatever the cause or circumstances, the phenomenon is quite plain. The local roads developed for purely local purposes on either side of the original Roman line, and that line, since there is no longer required any continuous traffic along it, disappears.

vi

(4) Lastly, we have the Peddars Way. It has presented a very difficult problem to all historians, but I think a solution is to be guessed at, though not to be too strongly affirmed. The Peddars Way runs as a main artery right through Suffolk and Norfolk. Its origin was clearly Stratford St. Mary’s, on the southern edge of Suffolk, and it was built to link up that water crossing with some harbour now disappeared on the Wash. Its use has dropped out; local roads are only concerned with it in a short section, and men argue thus: why was it ever made, and, if made, why did it fail as a means of communication? I think the answer is military. The Peddars Way never linked up any centres of population. It goes through land where men have never built cities or even large villages. But what it would do as a military road, what I think it was designed to do, was the holding of all that solid block of East Anglia which apparently exactly corresponds with the territory of the Iceni. For we must remember, as I have said above, that our county system is probably Roman in origin, and most of it corresponds to tribal divisions earlier even than the Roman administration. It is a point that has often been denied, but those who deny it fail to remark the analogy of the Continent, the evidence of Kent, Sussex, Dorsetshire, and Essex, apart from the striking list of that mass of counties which all centre round a Roman town or a town grown up as the suburb of a Roman town—Leicestershire, Worcestershire, Huntingdonshire, Gloucestershire, etc.

The Peddars Way cuts right across East Anglia through its very centre, so that a chain of stations along it commands the whole territory. It further divides that territory into two—a territory which was the scene of a great revolt in the beginning of the Roman occupation. It continued to subserve a certain function to the very end, because from it as a base one can radiate to threatened points upon the coast when the pirate raids began in the middle of the Roman occupation.

When, in the Dark Ages, the whole island fell into districts, fighting one against the other, each with its local king, the whole a chaos and a welter, the Peddars Way entirely lost its meaning and value. There was no longer one government or one army. There was no need for the controlling of a subject populace, for the populace had ceased to be subject save to its local chiefs. Such few men as still came over the North Sea were not, until the Danish invasion, enemies, and as the Peddars Way served no line of villages or of towns it fell completely out of use.

There is one very curious puzzle about this famous road, and which has never been settled, and to which I offer no more than an attempt at solution. We are fairly certain that one of the great Roman stations for the repelling of raids lay at Brancaster, upon the Wash. Yet the Peddars Way does not make for Brancaster, but for a point about four miles to the east along the coast. Why is this? There has been suggested a ferry across the Wash, but that hypothesis cannot be entertained. The distance is one of eleven miles over very difficult water, and leading to no important district. We have, I think, the key to the position in