CHAPTER V

CHINESE DRAGON LORE

Dragon Rain-god and Tiger-god of Mountains and Woods—Thunder-gods of East and West—Shark-gods as Guardians of Treasure—Dragon and Whale—Fish Vertebræ as Charms—Dragon and Dugong, Crocodile, Eel, &c.—Polynesian Dragon as “Pearl-mother”—Chinese Dragon and “Stag of the Sky”—Babylonian Sea-god and the Antelope, Gazelle, Stag, and Goat—Babylonian Dragon-slayers—Egyptian Gazelle- and Antelope-gods—Osiris as a Sea-god—African Antelope and Asiatic Dragon—The Serpent as “Water Confiner” in Egypt and India—Chinese Dragon has “Nature of Serpent”—Ancient Attributes of Far-Eastern Dragon—Dragon Battles—Dragons in East and West—Stones as “Dragon Eggs”—Dragon Mother and World Dragon—Dragons and Emperors.

The Chinese dragon is a strange mixture of several animals. Ancient native writers like Wang Fu inform us that it has the head of a camel, the horns of a stag, the eyes of a demon, the ears of a cow, the neck of a snake, the belly of a clam, the scales of a carp, the claws of an eagle, and the soles of a tiger. On its head is the chiʼih muh lump that (like a “gas-bag”) enables it to soar through the air. The body has three jointed parts, the first being “head to shoulders”, the second, “shoulders to breast”, and the third, “breast to tail”. The scales number 117, of which 81 are imbued with good influence (yang) and 36 with bad influence (yin), for the dragon is partly a Preserver and partly a Destroyer. Under the neck the scales are reversed. There are five “fingers” or claws on each foot. The male dragon has whiskers, and under the chin, or in the throat, is a luminous pearl. There is no denying the importance and significance of that pearl.

A male dragon can be distinguished from a female one by its undulating horn, which is thickest in the upper part. A female dragon’s nose is straight. A horned dragon is called kʼiu-lung and a hornless one chʼi-lung. Some dragons have wings. In addition there are horse-dragons, snake-dragons, cow-dragons, toad-dragons, dog-dragons, fish-dragons, &c., in China and Japan. Indeed, all hairy, feathered, and scaled animals are more or less associated with what may be called the “Orthodox Dragon”. The tiger is an enemy of the dragon, but there are references to tiger-headed dragons. The dragon is a divinity of water and rain, and the tiger a divinity of mountains and woods.1 The white tiger is a god of the west.

Like the deities of other countries, the Chinese dragon-god (and the Japanese dragon) may appear in different shapes—as a youth or aged man, as a lovely girl or an old hag, as a rat, a snake, a fish, a tree, a weapon, or an implement. But no matter what its shape may be, the dragon is intimately connected with water. It is a “rain lord” and therefore the thunder-god who causes rain to fall. The Chinese dragon thus links with the Aryo-Indian god Indra and other rain- and thunder-gods connected with agriculture, including Zeus of Greece, Tarku of Asia Minor, Thor of northern Europe, the Babylonian Marduk (Merodach), &c. There are sea-dragons that send storms like the wind-gods, and may be appeased with offerings. These are guardians of treasure and especially of pearling-grounds. Apparently the early pearl-fishers regarded the shark as the guardian of pearls. It seized and carried away the “robbers” who dived for oysters. The chief sea-god of China sometimes appeared in shark form—an enormous lion-headed shark.

Procopius, a sixth-century writer, says in this connection: “Sea-dogs are wonderful admirers of the pearl-fish, and follow them out to sea.… A certain fisherman, having watched for the moment when the shell-fish was deprived of the attention of its attendant sea-dog … seized the shell-fish and made for the shore. The sea-dog, however, was soon aware of the theft, and, making straight for the fisherman, seized him. Finding himself thus caught, he made a last effort, and threw the pearl-fish on shore, immediately on which he was torn to pieces by its protector.”2

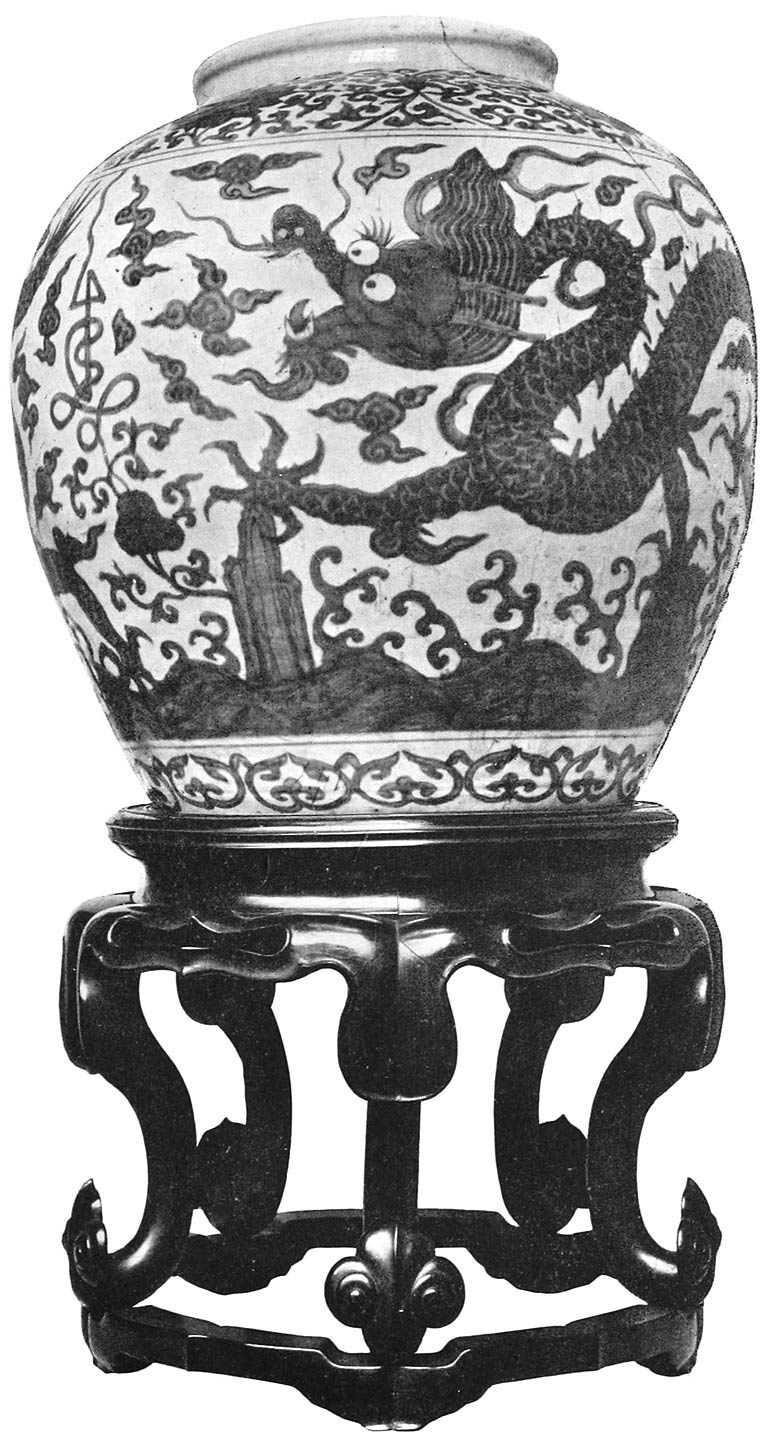

CHINESE DRAGONS AMONG THE CLOUDS

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

In Polynesia the natives have superstitious ideas about the shark. “Although”, says Ellis, “they would not only kill but eat certain kinds of shark, the large blue sharks, Squalus glaucus, were deified by them, and, rather than attempt to destroy them, they would endeavour to propitiate their favour by prayers and offerings. Temples were erected, in which priests officiated, and offerings were presented to the deified sharks, while fishermen, and others who were much at sea, sought their favour.”3 Polynesian gods, like Chinese dragons, appeared in various shapes. “One, for instance,” writes Turner, “saw his god in the eel, another in the shark, another in the turtle, another in the dog, another in the owl, another in the lizard; and so on throughout all the fish of the sea, and birds, and four-footed beasts and creeping things. In some of the shell-fish, even, gods were supposed to be present.”4 Here we meet again with the shell beliefs. The avatars of dragons had pearls. In an old Chinese work the story is told of a dragon that appeared in the shape of a little girl sitting at the entrance of a cave and playing with three pearls. When a man appeared, the child fled into the cave, and, reassuming dragon form, put the pearls in its left ear.5 As the guardian of pearls, the Chinese dragon links with the shark-god of the early pearl-fishers. There were varieties of these sea-gods. In Polynesia “they had”, Ellis has recorded, “gods who were supposed to preside over the fisheries, and to direct to their coasts the various shoals by which they were periodically visited.” The Polynesians invoked their aid “either before launching their canoes, or while engaged at sea”. It is of interest to find in this connection that the dragon had associations with the whale. Ancient mariners reverenced the whale. The Ligurians and Cretans carried home portions of the backbones of whales.6 The habit of placing spines of fish in graves is of great antiquity in Europe. The early seafarers who reached California during its prehistoric age perpetuated this very ancient custom. Beuchat gives an illustration of a kitchen-midden grave in California in which a whale’s vertebra is shown near the human skeleton.7 The swashtika appears among the pottery designs of early American pottery.8 The ancient Peruvians worshipped the whale, and the Maori dragon was compared to one.9 In Scottish folk-lore witches sometimes assume the forms of whales.

The dolphin, the bluish dugong10 (probably the “semi-human whale” referred to by Ælian), and other denizens of the sea were regarded as deities by ancient seafarers. De Groot, in his The Religious System of China, quoting from the Shan hai King, relates that in the Eastern Sea is a “Land of Rolling Waves”. In this region dwell sea-monsters that are shaped like cows and have blue bodies. They are hornless and one-legged. Each time they leave or enter the waters, winds arise and rain comes down. Their voice is that of thunder and their glare that of sun and moon.

The reference to the single leg may have been suggested by the fact that when the dugong dives the tail comes into view. This interesting sea-animal has been “recklessly and indiscriminately slaughtered” in historic times.

Classical writers referred to some of the strange monsters seen by their mariners as “sea-cows”. In like manner the Chinese have connected denizens of the deep with different land animals.

The religious beliefs associated with various sea and land animals cling to that composite god the dragon. In dealing with it, therefore, we cannot ignore its history, not only in China but in those countries that influenced Chinese civilization, while attention must also be paid to countries that, like China, were influenced by the early sea and land traders and colonists.

In Polynesia the dragon is called mo-o and mo-ko. “Their (the Polynesian) use of this word in traditions”, says W. D. Westervelt,11 “showed that they often had in mind animals like crocodiles and alligators, and sometimes they referred the name to any monster of great mythical powers belonging to the man-destroying class. Mighty eels, immense sea-turtles, large fish of the ocean, fierce sharks, were all called mo-o. The most ancient dragons of the Hawaiians are spoken of as living in pools or lakes.” Mr. Westervelt notes that “one dragon lived in the Ewa lagoon, now known as ‘Pearl Harbour’. This was Kane-kua-ana, who was said to have brought the pipi (oysters) to Ewa. She12 was worshipped by those who gather the shell-fish. When the oysters began to disappear about 1850, the natives said the dragon had become angry and was sending the oysters to Kahiki, or some far-away foreign land.” It is evident that such a belief is of great antiquity. The pearl under the chin of the Chinese dragon has, as will be seen, an interesting history.

But, it may be asked here, what connection has a mountain stag with the ancient pearl-fishers? As Wang Fu reminds us, the pearl-guarding Chinese dragon has “the horns of a stag”. It was sometimes called, De Groot states,13 “the celestial stag”—the “stag of the sky”. This was not merely a poetic image. The sea-god Ea of ancient Babylonia was in one of his forms “the goat fish”, as some put it. Professor Sayce says, in this connection, “Ea was called ‘the antelope of the deep’, ‘the antelope the creator’, ‘the lusty antelope’. He was sometimes referred to as ‘a gazelle’. Lubin, ‘a stag’, was a reduplicated form of elim, ‘a gazelle’. Both words were equivalent to sarru, ‘king’.”14 Whatever the Ea land animal was—whether goat, gazelle, antelope, or stag—it was associated with a sea-god who, according to Babylonian belief, brought the elements of culture to the ancient Sumerians, who were developing their civilization at the seaport of Eridu, then situated at the head of the Persian Gulf, in which pearls were found. Ea was depicted as half a land animal and half a fish, or as a man wrapped in the skin of a gigantic fish as Egyptian deities were wrapped in the skins of wild beasts. One of Ea’s names was Dagan, which was possibly the Dagon worshipped also by the Philistines and by the inhabitants of Canaan before the Philistines arrived from Kaphtor (the land of Keftiu, i.e. Crete).

Ea was associated with the dragon Tiamat, which his son Marduk (Merodach) slew. It is stated in Babylonian script that Ea “conferred his name” on Marduk. In other words, Marduk supplanted Ea and took over certain of his attributes, and part of his history. He was the god of Babylon, which supplanted other cities, formerly capitals; he therefore supplanted the chief gods of these cities.

Ea was originally the slayer of the dragon Tiamat and the conqueror of the watery abyss over which he reigned, supplanting the dragon.15 He became the dragon himself—the “goat fish” or “antelope of the deep”—the composite deity connected with animals deified by ancient hunters and fishers whose beliefs were ultimately fused with those of others with whom they were brought into close association in centres of culture. Ea, who had a dragon form, was connected with the serpent, or “worm”, as well as with the fish.

In Egypt Horus, Osiris, and Set were associated with the gazelle. Osiris was, in one of his forms, the River Nile. He was not only the Nile itself, but the controller of it; he was the serpent and soul of the Nile, and he was the ocean into which the Nile flowed, and the leviathan of the deep. In the Pyramid texts Osiris is addressed: “Thou art great, thou art green, in thy name of Great-green (sea); lo, thou art round as the Great Circle (Okeanos); lo, thou art turned about, thou art round as the circle that encircles the Hauneba (Ægeans)”.16 Osiris was thus the serpent (dragon) that, lying in the ocean, encircled the world. His son Horus is at one point in the Pyramid texts (Nos. 1505–8) narrative “represented as crossing the sea”.17 Horus was sometimes depicted riding on the back of a gazelle or antelope. The Egyptian antelope-god was in time fused with the serpent or dragon of the sea. Referring to the evidence of Frobenius18 in this connection, Professor Elliot Smith says that “in some parts of Africa, especially in the west, the antelope plays the part of the dragon in Asiatic stories”.19 When we reach India, it is found that the wind-god, Vayu, rides on the back of the antelope. Vayu was fused with Indra, the slayer of the dragon that controlled the water-supply, and, indeed, retained it by enclosing it as the Osiris serpent of Egypt, or the serpent-mother of Osiris, enclosed the water in its cavern during the period of “the low Nile”, before the inundation took place.20 After Osiris, as the water-confining serpent (dragon) was slain, the river ran red with his blood and rose in flood. Osiris, originally “a dangerous god”,21 was the “new” or “fresh” water of the inundation. “The tradition of his unfavourable character”, Breasted comments, “survived in vague reminiscences long centuries after he had gained wide popularity.” Osiris ultimately became “the kindly dispenser of plenty”, and his slayer, Set, originally a beneficent deity, was made the villain of the story and fused with the dragon Apep, the symbol of darkness and evil. This change appears to have been effected after the introduction of the agricultural mode of life. The Nile, formerly the destroyer, then became the preserver, sustainer, and generous giver of “soul substance” and daily bread.

When the agricultural mode of life was introduced into China the horned-dragon, or horned-serpent (for the dragon, Chinese writers remind us, has “the nature of a serpent”), became the Osiris water-serpent.

How a snake becomes a dragon is explained in the Shu i ki, which says: “A water-snake after 500 years changes into a kiao, a kiao after 1000 years changes into a lung;22 a lung after 500 years changes into a kioh-lung,23 and after 1000 years into a ying-lung.24” In Japan is found, in addition, the pʼan-lung (“coiled dragon”), which has not yet ascended to heaven.25 The “coiled dragon” is evidently the water-retaining monster.

The Chinese dragon is as closely connected with water as was the serpent form of Osiris with the Nile in ancient Egypt, and as was Indra with the “drought dragon” in India. The dragon dwells in pools, it rises to the clouds, it thunders and brings rain, it floods rivers, it is in the ocean, and controls the tides and causes the waters to ebb and flow as do its magic pearls (the “Jewels of Flood and Ebb”), and it is a symbol of the emperor. The Egyptian Pharaoh was an “avatar” of Osiris, or Horus,26 and the Chinese emperor was an “avatar” or incarnation of the dragon. As water destroys, the dragon is a destroyer; as water preserves and sustains, the dragon is a preserver and sustainer.

The dragon, as has been indicated, is essentially the Chinese water-god. “The ancient texts … are short,” says de Visser, “but sufficient to give us the main conceptions of old China with regard to the dragon. He was in those early days, just like now, the god of water, thunder, clouds, and rain, the harbinger of blessings, and the symbol of holy men. As the emperors are the holy beings of earth, the idea of the dragon being the symbol of imperial power is based upon this ancient conception.”27

The Chinese “dragon well” is usually situated inside a deep mountain cave. It was believed that the well owed its origin to the dragon. De Visser quotes, in this connection, from an ancient sage, who wrote: “When the yellow dragon, born from yellow gold a thousand years old, enters a deep place, a yellow spring dashes forth, and if from this spring some particles (fine dust) arise, these become a yellow cloud”. A famous dragon well is situated at the top of Mount Pien, in Hu-cheu. It flows from a cave, and is called “Golden Well Spring”. The cave is known as the “Golden Well Cave”, and is supposed to be so deep that no one can reach the end of it. There was a dragon well near Jerusalem.28 Other dragon wells are found as far west as Ireland and Scotland. A cave with wells, called the “Dropping Cave”, at Cromarty, has a demon in its inner recesses. The Corycian cave of the Anatolian Typhoon is one of similar character. According to Greek legend, this hundred-headed monster, from whose eyes lightning flashes, will one day send hail, floods, and rivers of fire to lay waste Sicilian farms.29 The floods of the River Rhone were supposed to be caused by the “drac”. In Egypt Set became the “roaring serpent”, who crept into a hole in the ground, “wherein he hid himself and lived”. He had previously taken the shapes of the crocodile and the hippopotamus to escape Horus, the Egyptian “dragon slayer”.

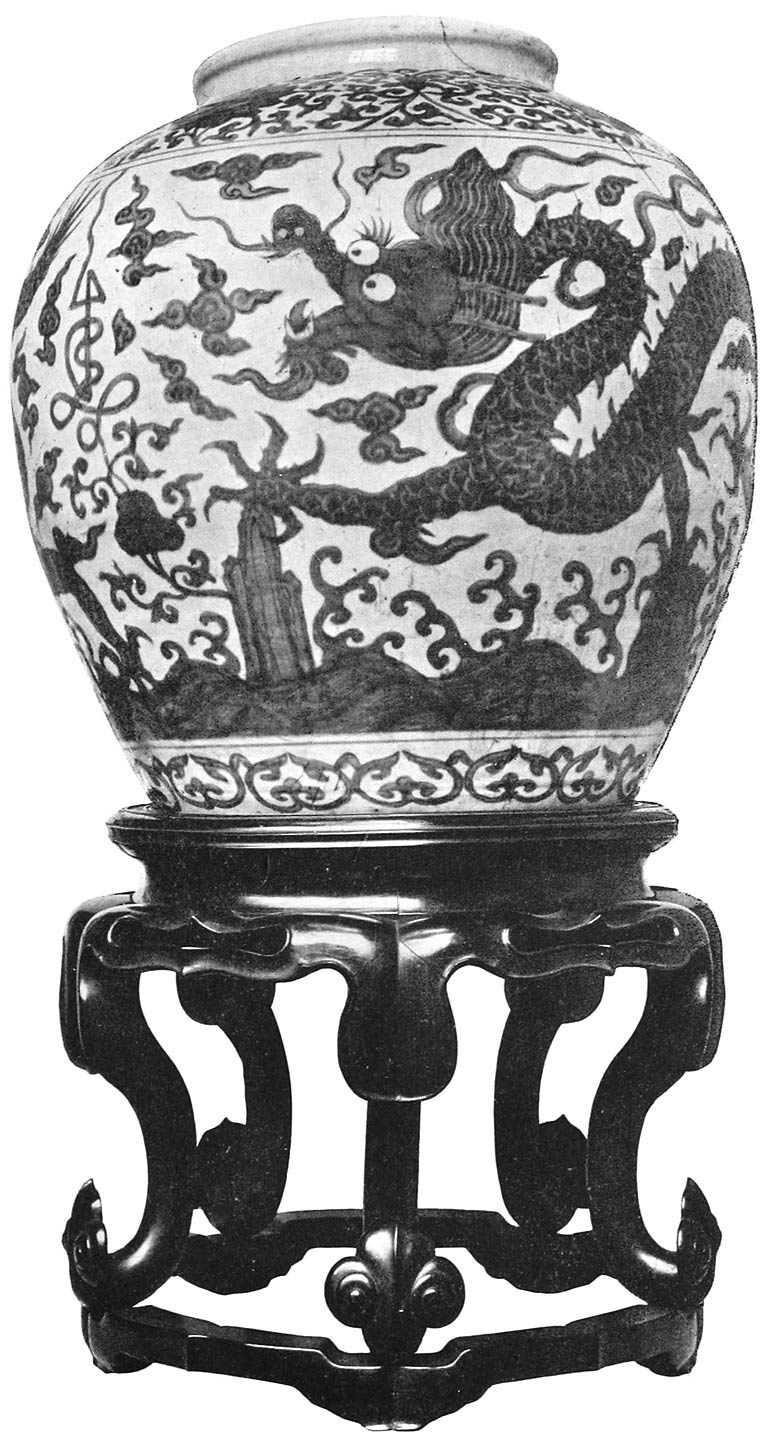

CHINESE DRAGON VASE WITH CARVED WOOD STAND

(Victoria and Albert Museum)

In China the season of drought is winter. The dragons are supposed to sleep in their pools during the dry spell, and that is why, in the old Chinese work, Yih Lin, it is stated that “a dragon hidden in water is useless”. The dragons are supposed to sleep so that they may “preserve their bodies”. They begin to stir and rise in spring. Soon they fight with one another, so that there is no need for a Horus, a Merodach, or an Indra to compel them, by waging battle, to bring benefits to mankind. The Chinese welcome what they called a “dragon battle” after the dry season. Thunder-storms break out, and rain pours down in torrents. If a number of dragons engage in battle, and the war in the air continues longer than is desired, the rivers rise in flood and cause much destruction and loss of life. As the emperor was closely connected with the chief dragon-god, social upheavals and war might result, it was anciently believed, in consequence of the failure of the priests and the emperor (the holiest of priests) to control the dragons. The dynasty might be overthrown by the indignant and ruined peasantry.

Among the curious superstitions entertained in China regarding dragon battles, is one that no mortal should watch them. It was not only unlucky but perilous for human beings to peer into the mysteries. De Visser quotes a Chinese metrical verse in this connection:

When they fight, the dragons do not look at us;

Why should we look at them when they are fighting?

If we do not seek the dragons,

They also will not seek us.30

In Gaelic Scotland the serpent, which is associated with the goddess Bride, sleeps all winter and comes forth on 1st February (old style), known as “Bride’s day”. A Gaelic verse tells in this connection:

The serpent will come from the home

On the brown day of Bride,

Though there should be three feet of snow

On the flat surface of the ground.31

As in China, a compact was made with the Bride serpent or dragon:

To-day is the Day of Bride,

The serpent shall come from his hole,

I will not molest the serpent,

And the serpent will not molest me.

It is evident that some very ancient belief, connected with the agricultural mode of life, lies behind these curious verses in such far-separated countries as Scotland and China. Bride and her serpent come forth to inaugurate the season of fruitfulness as do the battling dragons in the Far East.

When Chinese dragons fight, fire-balls and pearls fall to the ground. Pearls give promise of abundant supplies of water in the future. It is necessary, if all is to go well with the agriculturist, that the blue and yellow dragons should prevail over the others. The blue dragon is the chief spirit of water and rain, and this is the deity that presides during the spring season.

A glimpse is afforded of the mental habits of the early searchers for precious or sacred metals and jewels by the beliefs entertained in China regarding the origin of the dragon-gods. These were supposed to have been hatched from stones, especially beautiful stones. The colours of stones were supposed to reveal the characters of the spirits that inhabited them. In Egypt, for instance, the blue turquoise was connected with the mother-goddess Hathor, who was, among other things, a deity of the sky and therefore the controller of the waters above the firmament as well as of the Nile. She was the mother of sun and moon. She was appealed to for water by the agriculturists and for favourable winds by the seafarers. The symbol used on such occasions was a blue stone. It was a “luck stone” that exercised an influence on the elements controlled by the goddess. In the Hebrides a blue stone used to be reverenced by the descendants of ancient sea-rovers. Martin in his Western Isles tells of such a stone, said to be always wet, which was preserved in a chapel dedicated to St. Columba on the Island of Fladda. “It is an ordinary custom,” he has written, “when any of the fishermen are detained in the isle by contrary winds, to wash the blue stone with water all round, expecting thereby to procure a favourable wind, which, the credulous tenant living in the isle says, never fails, especially if a stranger wash the stone.” Why a “stranger”? Was this curious custom introduced of old by strangers who had crossed the deep? Had the washing ceremony its origin in the custom of pouring out libations practised by those who came from an area in which a complex religious culture had grown up, and where men had connected a deity, originally associated with the water-supply and therefore with the food-supply, with tempests and ocean-tides and the sky?

The Chinese, who called certain beautiful stones “dragon’s eggs”, believed that when they split, lightning flashed and thunder bellowed and darkness came on. The new-born dragons ascended to the sky. Before the dragons came forth, much water poured from the stone. As in the Hebrides, the dragon stone had, it would appear, originally an association with the fertilizing water-deity.

The new-born Chinese dragon is no bigger than a worm, or a baby serpent or lizard, but it grows rapidly. Evidently beliefs associated with the water-snake deities were fused with those regarding coloured stones. The snake was the soul of the river. Osiris as the Nile was a snake. His mother had, therefore, a snake form.

The haunting memory of the goddess-mother of water-spirits clings to the “dragon mother” of a Chinese legend related by ancient writers, a version of which is summarized by de Visser.32 Once, it runs, an old woman found five “dragon eggs” lying in the grass. When they split (as in Egypt “the mountain of dawn” splits to give birth to the sun), this woman carried the little serpents to a river and let them go. For this service she was given the power to foretell future events. She became a sibyl—a priestess. The people called her “The Dragon Mother.” When she washed clothes at the river-side, the fishes, who were subjects of dragons, “used to dance before her”.

In various countries certain fish were regarded as forms of the shape-changing dragon. The Gaelic dragon sometimes appeared as the salmon, and a migratory fish was in Egypt associated with Osiris and his “mother”.

When the Chinese “Dragon Mother” died, she was buried on the eastern side of the river. Why, it may be asked, on the eastern side? Was it because, being originally a goddess, she was regarded as the “mother” of the sun-god of the east—the mother who was “the mountain of dawn” and whose influence was concentrated in the blue stone? The Chinese dragon of the east is blue, and the blue dragon is associated with spring—the first-born season of the year. But apparently the dragons objected to the burial of the “Dragon Mother” on the eastern bank. The legend tells that they raised a violent storm, and transferred her grave to the western bank. Until the present age the belief obtains that there is always wind and rain near the “Dragon Mother’s Grave”. The people explain that the dragons love to “wash the grave”.

Here we find the dragons pouring out libations, as did the worshippers of the Great Mother who came from a distant land.

The god of the western quarter is white, and presides over the autumn season of fruitfulness. Just before the “birth” of autumn the Chinese address their prayers to the mountains and hills.

In ancient Egypt the conflict between the Solar and Osirian cults was a conflict between the “cult of the east” and the “cult of the west”. Professor Breasted notes that although Osiris is “First of the Westerners” (the west being his quarter) “he goes to the east (after death) in the Pyramid texts (of the solar cult) and the pair, Isis and Nepthys (the goddess), carry the dead into the east”. The east was the place where the ascent to the sky was made. In Egyptian solar theology it combined with the south. The rivalry between the two cults is reflected in one particular Pyramid text in which “the dead is adjured to go to the west in preference to the east, in order to join the sun-god!” But to the solar cult the east was “the most sacred of all regions”. In the Pyramid texts it is found that “the old doctrine of the ‘west’ as the permanent realm of the dead, a doctrine which is later so prominent, has been quite submerged by the pre-eminence of the east”.33

This east-and-west theological war, then, had its origin in Egypt. How did it reach China, there to be enshrined in the legend of the Dragon Mother? Can it be held that it was “natural” the Chinese should have invented a legend which had so significant and ancient a history in the homeland of the earliest seafarers?

The dragon-gods that presided over the seasons and the divisions of the world were five in number. At the east was the blue (or green) god associated with spring, at the west the white god associated with autumn, at the north the black god associated with winter (the Chinese season of drought), and at the south were two gods, the red and the yellow; the red god presided during the greater part of summer, the rule of the yellow god being confined to the last month.

The dragons were life-givers not only as the gods who presided over the seasons and ensured the food-supply, but as those who gave cures for diseases. The “Red Cloud herb” and other curative herbs were found after a thunderstorm beside the dragon-haunted pools. De Groot34 tells that fossil bones were called “dragon bones”, and were used for medicinal purposes. The dragons were supposed to cast off their bones as well as their skins. Bones of five colours (the colours of the five dragons) were regarded as the most effective. White and yellow bones came next in favour. Black bones were “of inferior quality”. The Shu King, a famous Chinese historical classic,35 tells that the dragons’ bones come from Tsin land. It is noted that the five-coloured ones are the best. The blue, yellow, red, white, and black ones, according to their colours, correspond with the viscera, as do the five chih (felicitous plants), the five crystals (shih ying), and the five kinds of mineral bole (shih chi). De Groot36 gives the colours connected with the internal organs as follows:

1. Blue—liver and gall.

2. White—lungs and small intestines.

3. Red—heart and large intestines.

4. Black—kidneys and bladder.

5. Yellow—spleen and stomach.

Apparently the special curative quality of a dragon’s bone was revealed by its colour. The gods of the various “mansions” influenced different organs of the human body.

In ancient Egypt the internal organs were placed in jars and protected by the Horuses of the cardinal points. The god of the north had charge of the small viscera, the god of the south of the stomach and large intestines, the god of the west of liver and gall, and the god of the east of heart and lungs. The Egyptian north was red and symbolized by the Red Crown, and the south was white and symbolized by the White Crown.

In Mexico the colours white, red, and yellow were connected with different internal organs, and black with a disembowelled condition.

It is evident that the sea and land traders carried their strange stocks of medical knowledge over vast areas. It is not without significance to find in this connection that, according to Chinese belief, there was an island on which dragons’ bones were found.

The dragons are not only rain-gods and gods of the four quarters and the seasons, but also “light-gods”, connected with sun and moon, day and night. In the Yih lin there is a reference to a black dragon which vomits light and causes darkness to turn into light. The mountain dragon of Mount Chung is called the “Enlightener of Darkness”. “When it opens its eyes it is day, when it shuts its eyes it is night. Blowing he makes winter, exhaling he makes summer. The wind is its breath.”37

In like manner the Egyptian Ra and Ptah are universal gods, the sun and moon being their “eyes”. Even Osiris, as far back as the Pyramid period, was the source of all life and a world-god. He was addressed: “The soil is on thy arm, its corners are upon thee as far as the four pillars of the sky. When thou movest the earth trembles.… As for thee, the Nile comes forth from the sweat of thy hands. Thou spewest out the wind.…”38 Osiris sent water to bring fertility as do the dragons, air for the life-breath of man and beast, and also light, which was, of course, fire (the heat which is life).

The idea of the life-principle being in fire and water lies behind Wang Fu’s statement: “Dragon fire and human fire are opposite. If dragon fire comes into contact with wetness, it flames; and if it meets water, it burns. If one drives it (the dragon) away by means of fire, it stops burning and its flames are extinguished.”39 Celestial fire is something different from ordinary fire. The “vital spark” is of celestial origin—purer and holier than ordinary fire. Dragon skins, even when cast off, shine by night. So do pearls, coral, and precious stones “shine in darkness” in the Chinese myths.

One traces the influence of the solar cult in the idea that the dragon’s vital spirit is in its eyes. It is because iron blinds a dragon that it fears that metal. In Egypt the eye of Horus is blinded by Set, whose metal is iron.

There is a quaint mixture of religious ideas in the Chinese custom of carrying in procession through the streets, on the 15th of the first month, a dragon made of bamboo, linen, and paper. In front of it is borne a red ball. De Groot says that this is the azure dragon, the head of which rose as a star to usher in spring at the beginning.40 In like manner the Egyptian “spring” is ushered in by the star Sirius, the mother of the sun, from which falls a tear that causes the inundation. But although the red ball may have been a solar symbol, it is also connected with the moon. The Chinese themselves call the ball “The Pearl of Heaven”—that is, “the moon”. An inscription on porcelain brings this out clearly. Mr. Blacker has translated the text below two dragons rushing towards a ball as “A couple of dragons facing the moon”.41 The dragons were not only moon- and sun-“devourers” who caused eclipses, but guardians of these orbs in their capacities as gods of the four quarters.

The all-absorbing dragon appears even as a vampire. A tiger-headed dragon with the body of a snake seizes human beings, covers them with saliva, and sucks blood from under their armpits. “No blood is left when they stop sucking.”42 In Japanese legends dragons as white eels draw blood from the legs of horses that enter a river.43 Evil or sick dragons send bad rain.

The gods ride on dragons, and therefore emperors and holy men can also use them as vehicles. Yu, the founder of the Hea Dynasty, had a carriage drawn by two dragons. Ghosts sometimes appear riding on dragons and wearing blue hats. The souls of the dead are conveyed to the Celestial regions by the winged gods. Dragons appear when great men are born.44 Emperors had dragon ancestors. The Emperor Yaou was the son of a red dragon; one Japanese emperor had a dragon’s tail, being a descendant of the sea-god.45

In the next chapter it will be shown that in Chinese dragon-lore it is possible to detect with certainty the sources of certain “layers” that were superimposed on primitive conceptions regarding these deities.