CHAPTER IV

THE WORLD-WIDE SEARCH FOR WEALTH

Religious Incentive of Quest of Wealth—Sacredness of Precious Metals and Stones—Gold and the Sky Deities—Iron as the Devil’s Metal—Chinese Dragons and Metals—Gold good and Silver bad in India—Dragons and Copper—Sulphuret of Mercury as “Dragon’s Blood” and Elixir of Life—Dragons and Pearls—The “Jewel that grants all Desires”—Story of Buddhist Abbot and the Sea-God—“Jewels of Flood and Ebb”—Japan and Korea—Sea-god as “Abundant Pearl Prince”—Pearl Fishers—Early History of Sea-trafficking—Traders and Colonists—Cow, Moon, Shells, and Pearls connected with Mother-goddess—The Sow Goddess—Shell Beliefs—Culture Drifts and Culture Complexes.

There can be no doubt as to the reasons why Solomon sought to emulate the maritime activities of the Phœnicians who had been bringing peacocks from India, silver from Spain, and gold from West Africa and elsewhere long before his day.

“And King Solomon made a navy of ships in Ezion-geber, which is beside Eloth, on the shore of the Red Sea, in the land of Edom. And Hiram sent in the navy his servants, shipmen that had knowledge of the sea, with the servants of Solomon. And they came to Ophir, and fetched from thence gold, four hundred and twenty talents, and brought it to King Solomon.”1

When the Queen of Sheba visited Jerusalem she was accompanied by “camels that bare spices, and very much gold, and precious stones”.2 About seven centuries before Solomon’s day, Queen Hatshepsut of Egypt, to whom reference was made in the last chapter, had emulated the feats of her ancestors by sending a fleet to Punt (Somaliland or British East Africa) to bring back, among other things, myrrh trees for her new temple. The myrrh was required “for the incense in the temple service”.3 Ancient mariners set out on long voyages, not only on the quest of wealth, but also of various articles required for religious purposes. Indeed, the quest of wealth had originally religious associations. Gold, silver, copper, pearls, and precious stones were all sacred, and it was because of their connection with the ancient deities that they were first sought for. The so-called “ornaments” worn by our remote ancestors were charms against evil and ill luck. Metals were similarly supposed to have protective qualities. Iron is still regarded in the Scottish Highlands as a charm against fairy attack. In China it is a protection against dragons. The souls of the Egyptian dead were “charmed” in the other world by the amulets placed in their tombs. When the Pharaoh’s soul entered the boat of the sun-god he was protected by metals. “Brought to thee”, a Pyramid text states, “are blocks of silver and masses of malachite.”4 Gold was the metal of the sun-god and silver of the deity of the moon. Horus had associations with copper, and Ptah, the god of craftsmen, with various metals. Iron was “the bones of Set”, the Egyptian devil. In Greece and India the mythical ages were associated with metals, and iron was the metal of the dark age of evil (the Indian “Kali Yuga”).

In China the metals have similarly religious associations. The dragon-gods of water, rain, and thunder are connected with gold of various hues—the “golds” coloured by the alchemists by fusion with other metals. Thus we have Chinese references to red, yellow, white, blue, and black gold, as in the following extract:

“When the yellow dragon, born from yellow gold a thousand years old, enters a deep place, a yellow spring dashes forth; and if from this spring some particles (fine dust) arise, these become a yellow cloud.

“In the same way blue springs and blue clouds originate from blue dragons, born from blue gold eight hundred years old; red, white, and black springs and clouds from red, white, and black dragons born from gold of same colours a thousand years old.”5

In Indian Vedic lore gold is a good metal and silver a bad metal. One of the Creation Myths states in this connection:

“He (Prajapati) created Asuras (demons). That was displeasing to him. That became the precious metal with the bad colour (silver). This was the origin of silver. He created gods. That was pleasing to him. That became the precious metal with the good colour (gold). That was the origin of gold.”6

The dragon of the Far East is associated with copper as well as gold. In the Japanese Historical Records the story is told how the Emperor Hwang brought down a dragon so that he might ride on its back through the air. He first gathered copper on a mountain. Then he cast a tripod. Immediately a dragon, dropping its whiskers, came down to him. After the monarch had used the god as an “airship”, no fewer than seventy of his subjects followed his example. Hwang was the monarch who prepared the “liquor of immortality” (the Japanese “soma”) by melting cinnabar (sulphuret of mercury, known as “dragon’s blood”). Chinese dragons, according to Wang Fu in ’Rh ya yih, dread iron and like precious stones. In Japan the belief prevailed that if iron and filth were flung into ponds the dragons raised hurricanes that devastated the land. The Chinese roused dragons, when they wanted rain, by making a great noise and by throwing iron into dragon pools. Iron has “a pungent nature” and injures the eyes of dragons, and they rise to protect their eyes. Copper has, in China, associations with darkness and death. The “Stone of Darkness” is hollow and contains water or “the vital spirit of copper”.7 Dragons are fond of these stones and of beautiful gems.8

The dragon-shaped sea-gods of India and the dragon-gods of China and Japan have close associations with pearls. In a sixth-century Chinese work,9 it is stated that pearls are spit out by dragons. Dragons have pearls “worth a hundred pieces of gold” in their mouths, under their throats, or in their pools. When dragons fight in the sky, pearls fall to the ground. De Groot10 makes reference to “thunder pearls” that dragons have dropped from their mouths. These illuminate a house by night. In Wang Fu’s description of the dragon it is stated that a dragon has “a bright pearl under its chin”.

A mountain in Japan is called Ryushuho, which means “Dragon-Pearl Peak”. It is situated in Fuwa district of Mino province, and is associated in a legend with the Buddhist temple called “Cloud-Dragon Shrine”. When this temple was being erected, a dragon, carrying a pearl in its mouth, appeared before one of the priests. Mountain and sanctuary were consequently given dragon names.

The “jewel that grants all desires” is known in India, China, and Japan. A Japanese story relates that once upon a time an Indian Buddhist abbot, named Bussei (Buddha’s vow), set out on a voyage with purpose to obtain this jewel (a pearl) which was possessed by “the dragon king of the ocean”. In the midst of the sea the boat hove to while Bussei performed a ceremony and repeated a charm, causing the dragon-king to appear. The abbot, making a mystic sign, then demanded the pearl; but the dragon deceived him and nullified the mystic sign. Rising in the air, “the King of the Ocean” caused a great storm to rage. The boat was destroyed and all on board it, except Bussei, were drowned. Bussei afterwards migrated from southern India to Japan, accompanied by Baramon (“Wall-gazing Brahman”).

The “Jewels of Flood and Ebb” were jewels that granted desires. In Japanese legend these were possessed by the dragon king (Sagara), whose kingdom, like that of the Indian Naga monarch and that of the Gaelic ruler of “Land Under-Waves”, is situated at the bottom of the sea. The white jewel is called “Pearl of Ebb”, and the blue jewel “Pearl of Flood”.

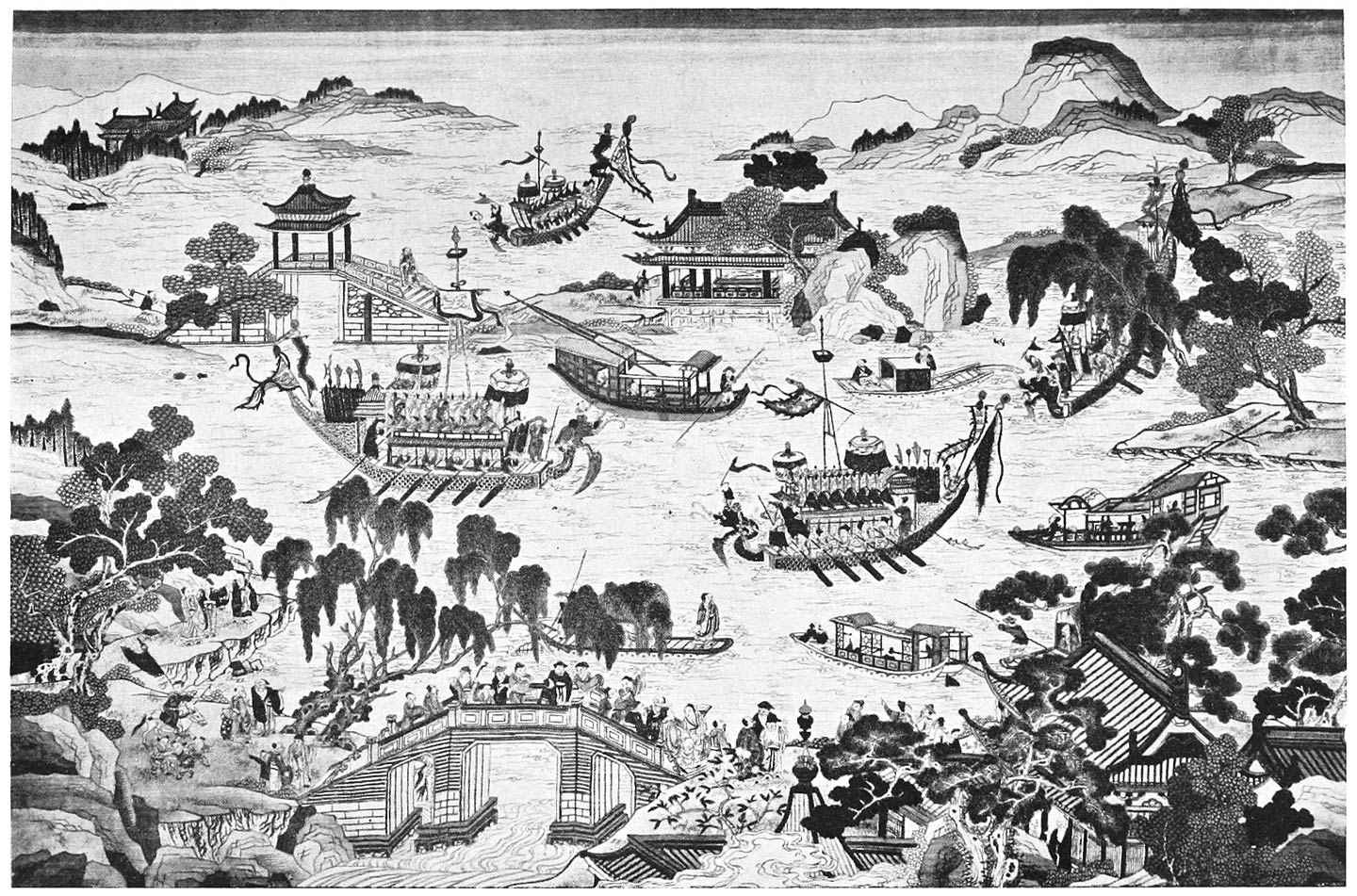

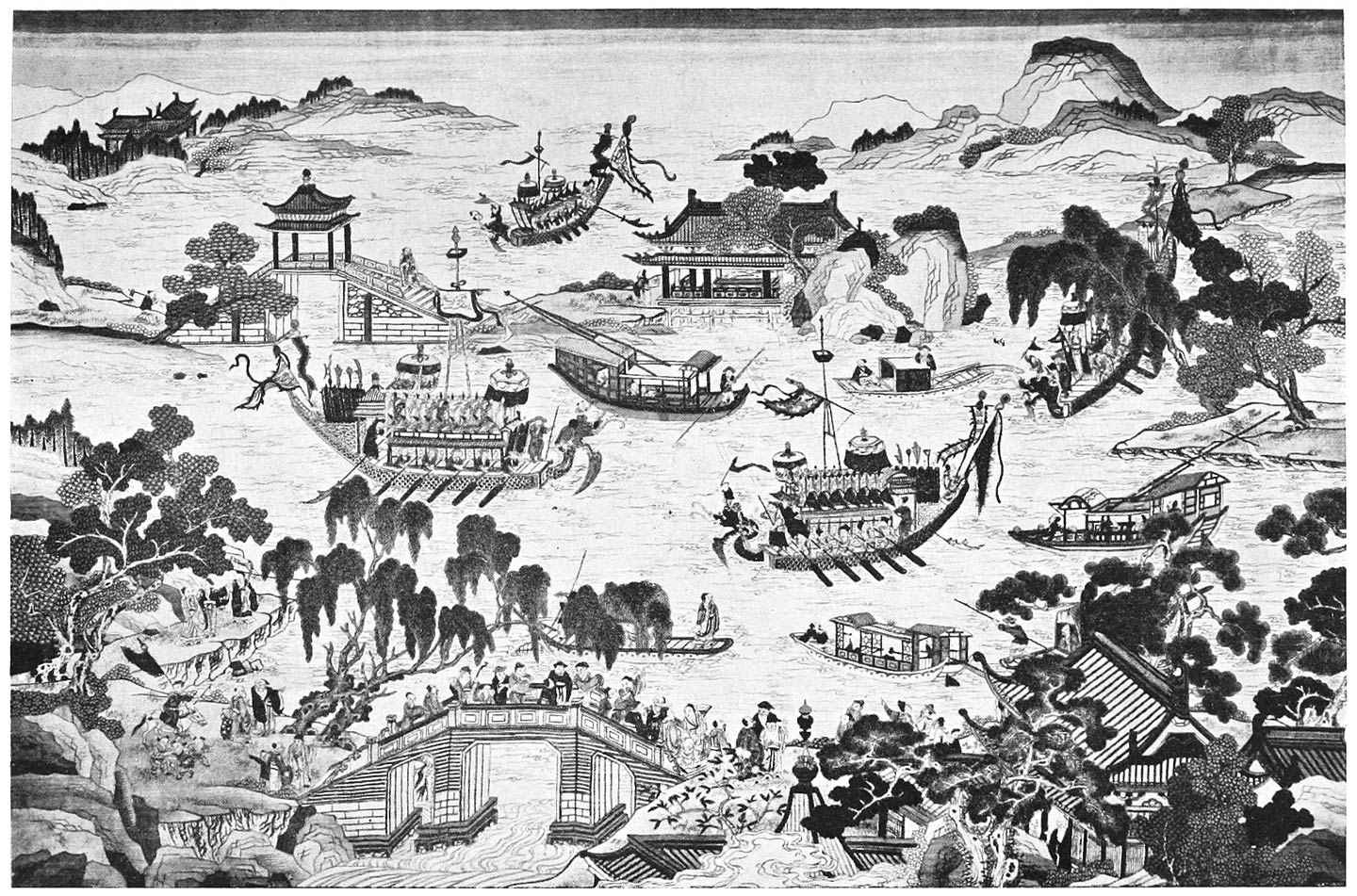

CHINESE DRAGON-BOAT FESTIVAL

From a picture woven in coloured silks and gold thread in the Victoria and Albert Museum

A Japanese story relates that the Empress Jingo obtained from a sea-god a “jewel that grants all desires”. During her reign a great fleet went to Korea to obtain tribute. The Korean fleet went out to meet it, but when it was drawn up for battle, a Japanese god cast into the sea the “Pearl of Ebb”, and immediately the waters withdrew, leaving both fleets stranded. The resolute King of Korea, not to be daunted, leapt on to the dried sea-bed, and, marshalling his troops there, advanced at the head of them to attack and destroy the Japanese fleet. Then the Japanese god flung the “Pearl of Flood” into the sea. No sooner was this done than the waters returned and drowned large numbers of Koreans. Then a tidal wave swept over the Korean shore, while the troops prayed for their lives in vain. Not until the “Pearl of Ebb” was thrown once again into the sea did the waters retreat from the land.

After these miraculous and disastrous manifestations, the King of Korea was glad to make peace, and sent out three vessels laden with tribute to the empress, who had conquered the enemy without the loss of a single Japanese soldier or sailor, or even a single drop of Japanese blood.

Other names of the Japanese sea-god Sagara11 are Oho-watatsumi (“sea lord, or sea snake”), and Toyo-tama hiko no Mikoto (“Abundant Pearl Prince”), and he has a daughter named Toyo-tama-bime (“Abundant Pearl Princess”).12 During storms, sailors threw jewels into the sea to pacify the dragon king.

Chinese emperors, like the Egyptian Pharaohs, had dragon boats which were used in connection with religious rain-getting ceremonies. They had also the bird boats called “yih”. Mr. Wells Williams refers to the yih as “a kind of sea-bird that flies high, whose figure is gaily painted on the sterns of junks, to denote their swift sailing”. He adds that “the descriptions are contradictory, but its picture rudely resembles a heron”.13

It will be gathered from the evidence summarized above that the seafaring activities of the Chinese and Japanese had close associations with the search for precious metals and stones and pearls on the part of those who introduced the Egyptian type of vessels into their waters. With these ships went many customs and beliefs that became mixed with local customs and beliefs. New modes of life were introduced, and, with these, new modes of thought. Nothing persists like immemorial customs, myths, and religious beliefs associated with a particular mode of life.

Before the culture-complexes of China and Japan are investigated, so that local elements may be sifted out from the overlying mass of imported elements, it would be well to deal with the history of the search for wealth across the oceans of the world.

It is necessary, therefore, to turn back again to the cradle of shipbuilding and maritime enterprise—to ancient Egypt with its wonderful civilization of over 3000 years that sent its influences far and wide. Whether or not the Egyptians ever reached China or Japan, we have no means of knowing. Pauthier’s view in this connection has come in for a good deal of destructive criticism. He referred to a Chinese tradition that about 1113 B.C. the Court was visited by seafarers from the kingdom of “Nili”, and suggested that they came from the Nile valley.14 The “Nili”, “Nēlē”, or “Nērē” folk, according to others, came from the direction of Japan or from beyond Korea. References to them are somewhat obscure. It does not follow that because Egyptian ships reached China, they were manned by Egyptians. Ships were, like potter’s wheels, adopted by folks who may never have heard of Egypt. A culture flows far beyond the areas reached by those who have given it a definite character, just as the Bantu dialects have penetrated to areas in Africa far beyond Bantu control.

What motives, then, stimulated maritime enterprise at the dawn of the history of sea-trafficking? What attracted the ancient mariners? If it was wealth, what was “wealth” to them?

The answer to the last query is that wealth was something with a religious significance. Gold was searched for, but not, to begin with, for the purpose of making coins. There was no coinage. Gold was a precious metal in the sense that it brought luck, and to the ancient people “luck” meant everything they yearned for in this world and the next.

As far back as the so-called “Palæolithic period” in western Europe, there was, as has been noted, a systematic search for wealth in the form of sea-shells. The hunters in central Europe imported shells from the Mediterranean coast and used them as amulets. These imported shells are found in their graves. In Ancient Egypt, shells were carried from the Red Sea coast, as well as from the Mediterranean coast, long before the historical period begins. The evidence of the grave-finds shows that Red Sea pearl-shell and Red Sea cowries were in use for religious purposes. “Millions of them”, as Maspero has noted, have been found in Ancient Egyptian graves. In time, pearls came into use, not only pearls from Nile mussels, but from oysters found in the southern part of the Gulf of Aden. As shipping developed, the pearl-fishers went farther and farther in search of pearls. The famous ancient pearl area in the Persian Gulf was discovered and drawn upon at some remote period. No doubt the pearls worn by Assyrian and Persian monarchs came, in part, from the Persian Gulf. At what period Ceylon pearls were first fished for it is impossible to say. Of one thing we can be certain, however. They were fished for by men who used the Egyptian type of vessel.

The migrating and trading pearl-fishers carried their beliefs with them from land to land. Almost everywhere are found the same beliefs and practices connected with shells and pearls. These beliefs and practices are of a highly complex character—so complex, indeed, that they must have had an area of origin in which they reflected the beliefs and customs of a people with a history of their own. The pearl, for instance, was connected with the moon, with the goddess who was the Great Mother, and with the sun and the sun-god. Venus (Aphrodite) was sea-born. She was lifted from the sea, by Tritons, seated on a shell. She was the pearl—the vital essence of the magic shell, and she was the moon, the “Pearl of Heaven”. The pearl, like the moon, was supposed to exercise an influence over human beings. In Egypt, the Mother Goddess was symbolized by a cow, and cow, moon, pearl, and shell were connected in an arbitrary way.

In those areas in which the Mother Goddess was symbolized by the sow, the shell was likewise connected with her. The Greeks applied to the cowry a word that means “little pig”; this word had a special reference to the female sex. The Romans called the shell “porci”, and porcelain has a like derivation.15 As has been shown, women were connected with hand-made pottery, and the pot was a symbol of the Great Mother. In Scotland, certain shells are still referred to as “cows” and “pigs”. They were anciently believed to promote fertility and bring luck. The custom of placing shells on window-sills, at doors, in fire-places, and round garden plots still obtains in parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Some low-reliefs of mother goddesses with baskets of fruit, corn, &c., surviving from the Romano-British period, which have been found in various parts of Britain, have shell-canopies. The Romans “took over” the goddesses of the peoples of western Europe on whom they imposed their rule, as they took over the Greek pantheon.

Following the clues afforded by the evidence of ships, it is found that the early pearl-fishers coasted round from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf, round India to the Bay of Bengal, round the Malay Peninsula to the China Sea, northwards to the Sea of Okhotsk, and on to the western coast of North America. Oceania was peopled by the ancient mariners, who appear to have reached by this route the coast of South America. As we have seen, Africa was circumnavigated. Western and north-western Europe and the British Isles were reached at a very early period.

The ancient seafarers searched not only for pearls and pearl-shell, but also for gold, silver, copper, tin, and other metals and for precious stones. They appear to have founded trading colonies that became centres from which cultural influences radiated far and wide. From these colonies expeditions set out to discover new pearling grounds and new mineral fields. The search for wealth, having a religious incentive, caused, as has been said, the spread of religious ideas. In different countries, imported beliefs and customs became mingled with local beliefs and customs, with the result that in many countries are found “culture complexes” which have a historical significance—reflecting as they do the varied experiences of the peoples and the influences introduced into their homelands at various periods.

In the next chapter it will be shown how the dragon of China has a history that throws much light on the early movements of explorers and traders who carried the elements of complex cultures into far distant lands.