CHAPTER VII

DRAGON FOLK-STORIES

How Fish became Chinese Dragons—Fish forms of Teutonic and Celtic Gods—Dragon-slayers eat Dragons’ Hearts—The “Language of Birds”—Heart as Seat of Intelligence—Babylonian Dragon-Kupu—Polynesian Dragon-Kupua—Dragons and Medicinal Herbs—Story of Chinese Herbalist and “Red Cloud Herb”—“Boy Blue” and Red Carp as Forms of Black Dragon—Ignis Fatuus as “Dragon Lanterns”—“Heart Fire”—Story of Priest and Dragon-woman—The “Fire Nail” in Japan and Polynesia—The “Faith Cure” in Japan—The Magic Rush-mat—Grave Reed-mats, Skins, and Linen Wrappings—The Ephod—Melusina in Far East—Story of Wu and the Thunder Dragon.

In Chinese and Japanese folk-stories the dragons have fish forms or avatars. They may be eels, carps, or migratory fish like the salmon. It is believed that those fish that ascend a river’s “dragon gate” become dragons, while those that remain behind continue to be fish. Dragons are closely associated with waterfalls. They haunt in one or other of their forms the deep pools below them.

In western European stories, dragons and gods of fire and water assume the forms of fish, and hide themselves in pools. Loki of Icelandic legend has a salmon form. When the gods pursue him, he hides in Franang’s stream, or “under the waters of a cascade called Franangurfors”.1 After he is caught and bound, Loki is tortured by a serpent. When he twists his body violently, earthquakes are caused. He is closely associated with the “dragon-woman”, and is the father of monsters, including the moon-swallowing wolf-dragon.

Andvari, the guardian of Nibelung treasure, has a pike form.2

In Gaelic legend the salmon is the source of wisdom and of the power to foretell events. Finn (Fionn) tastes of the “Salmon of Knowledge” when it is being cooked, and immediately becomes a seer. Michael Scott, in like manner, derives wisdom from the “juices” of the white snake. The salmon is, in Gaelic, a form of the dragon. The dragon of Lough Bel Séad3 (Lake of the Jewel Mouth), in Ireland, was caught “in the shape of a salmon”.

Sigurd, the dragon-slayer of Norse Icelandic stories, eats the dragon’s heart, and at once understands the language of birds. So does Siegfried of Germanic romance. The birds know the secrets of the gods. They are themselves forms of the gods. Apollonius of Tyana acquired wisdom by eating the hearts of dragons in Arabia.

In ancient Egypt the heart was not only the seat of life, but the mind, and therefore the source of “words of power”. The Hebrews and many other peoples used “heart” when they wrote of “mind”.4 Ptah, god of Memphis, was the “heart” (mind) of the gods. The “heart” fashioned the gods. Everything that is came into existence by the thought of the “heart” (mind).

The Egyptian belief about the power of the “heart” (the source of magic knowledge, and healing, and creative power) lies behind the stories regarding heroes eating dragons’ hearts. In an Egyptian folk-tale the dragon-slayer does not eat the heart of the reptile god, but gets possession of a book of spells, and, on reading these, acquires knowledge of the languages of all animals, including fish and birds.5

When, however, we investigate the dragon beliefs of ancient Babylonia, we meet with a reference to the Ku-pu as the source of divine power and wisdom. After Merodach (Marduk) the dragon-slayer kills Tiamat, the “mother dragon”, a form of the mother-goddess, he “divides the flesh of the Ku-pu, and devises a cunning plan”. As the late Mr. Leonard W. King pointed out,6 Ku-pu is a word of uncertain meaning. It did not signify the heart, because it had been previously stated in the text that Merodach severed her inward parts, he pierced her heart.

Jensen has suggested that Ku-pu signifies “trunk, body”. It is more probable that the Ku-pu was the seat of the soul, mind, and magical power; the power that enabled the slain reptile to come to life again in another form.7

It may be that a clue is afforded in this connection by the Polynesian idea of Kupua. Mr. Westervelt, who has carefully recorded what he has found, writes regarding the Mo-o (dragons) of the Hawaiians:

“Mighty eels, immense sea turtles, large fish of the ocean, fierce sharks, were all called mo-o. The most ancient dragons of the Hawaiians are spoken of as living in pools or lakes. These dragons were known also as Kupuas, or mysterious characters, who could appear as animals, or human beings, according to their wish. The saying was, ‘Kupuas have a strange double body!’ ”

The Polynesian beliefs connected with the Kupuas are highly suggestive. Mr. Westervelt continues:

“It was sometimes thought that at birth another natural form was added, such as an egg of a fowl or a bird, or the seed of a plant, or the embryo of some animal which, when fully developed, made a form which could be used as readily as the human body. These Kupuas were always given some great magic power. They were wonderfully strong, and wise, and skilful.

“Usually the birth of a Kupua, like the birth of a high chief, was attended with strange disturbances in the heavens, such as reverberating thunder, flashing lightning, and severe storms which sent the abundant red soil of the islands down the mountain-sides in blood-red torrents, known as ka-ua-koko (the blood rain). The name was also given to misty, fine rain when shot through by the red waves of the sun.”

All the dragons of Hawaii were descended from Mo-o-inanea (the self-reliant dragon), a mother-goddess. She had a dual nature, “sometimes appearing as a dragon, sometimes as a woman”. Hawaiian dragons also assumed the forms of large stones, some of which were associated with groves of hau trees; on these stones ferns and flowers were laid and referred to as “kupuas”.8

In China the dragon’s kupua (to use the Polynesian term) figures in various stories. We meet with the “Red Cloud herb”, or the “Dragon Cloud herb”, which cures diseases. It is the gift of the dragon, and apparently a dragon kupua. Other curative herbs are the “dragon-whisker’s herb” and the “dragon’s liver”, a species of gentian, which is in Japan a badge of the Minamoto family. The “dragon’s spittle” had curative qualities, the essence of life being in the body moisture of a deity. The pearl, which the dragon spits out, has, or is, “soul substance”. The plum tree was in China connected with the dragon. A story tells that once a dragon was punished by having its ears cut off. Its blood fell on the ground, and a plum tree sprang up; it bore fleshy fruit without kernels.9 When in an ancient Egyptian story the blood of the Bata bull falls to the ground two trees containing his soul-forms grow in a night.10

A Chinese “Boy Blue” story deals with the search made by Wang Shuh, a herbalist, for the Red Cloud herb. He followed the course of a mountain stream on a hot summer day, and at noon sat down to rest and eat rice below shady trees beside the deep pool of a waterfall. As he lay on the bank, gazing into the water, he was astonished to see in its depths a blue boy, about a foot in height, with a blue rush in his hand, riding on the back of a red carp, without disturbing the fish, which darted hither and thither. In time the pair came to the surface, and, rising into the air, turned towards the east. Then they went swiftly in the direction of a bank of cloud that was creeping across the blue sky, and vanished from sight.

The herbalist continued to ascend the mountain, searching for the herb, and when he reached the summit was surprised to find that the sky had become completely overcast. Great masses of black and yellow clouds had risen over the Eastern Sea, and a thunder-storm was threatening. Wang Shuh then realized that the blue boy he had seen riding on the back of the red carp was no other than the thunder-dragon. He peered at the clouds, and perceived that the boy and the carp11 had been transformed into a black kiao (scaled dragon). He was greatly alarmed, and concealed himself in a hollow tree.

Soon the storm burst forth in all its fury. The herbalist trembled to hear the voice of the black thunder-dragon and to catch glimpses of his fiery tongue as he spat out flashes of lightning. Rain fell in torrents, and the mountain stream was heavily swollen, and roared down the steep valley. Wang Shuh feared that each moment would be his last.

In time, however, the storm ceased and the sky cleared. Wang Shuh then crept forth from his hiding-place, thankful to be still alive, although he had seen the dragon. He at once set out to return by the way he had come. When he drew near to the waterfall he was greatly astonished to hear the sound of sweet humming music. Peering through the branches of the trees, he beheld the little blue boy riding on the back of the red carp, returning from the east and settling down on the surface of the pool. Soon the boy was carried into the depths and past the playful fish again.

Struck with fear, the herbalist was for a time unable to move. When at length he had summoned sufficient strength and courage to go forward, he found that the boy and the carp had vanished completely. Then he perceived that the Red Cloud herb, for which he had been searching, had sprung up on the very edge of the swirling water. Stooping, he plucked it greedily. As soon as he had done so, he went scampering down the side of the mountain. On reaching the village, Wang told his friends the wonderful story of his adventure and discovery.

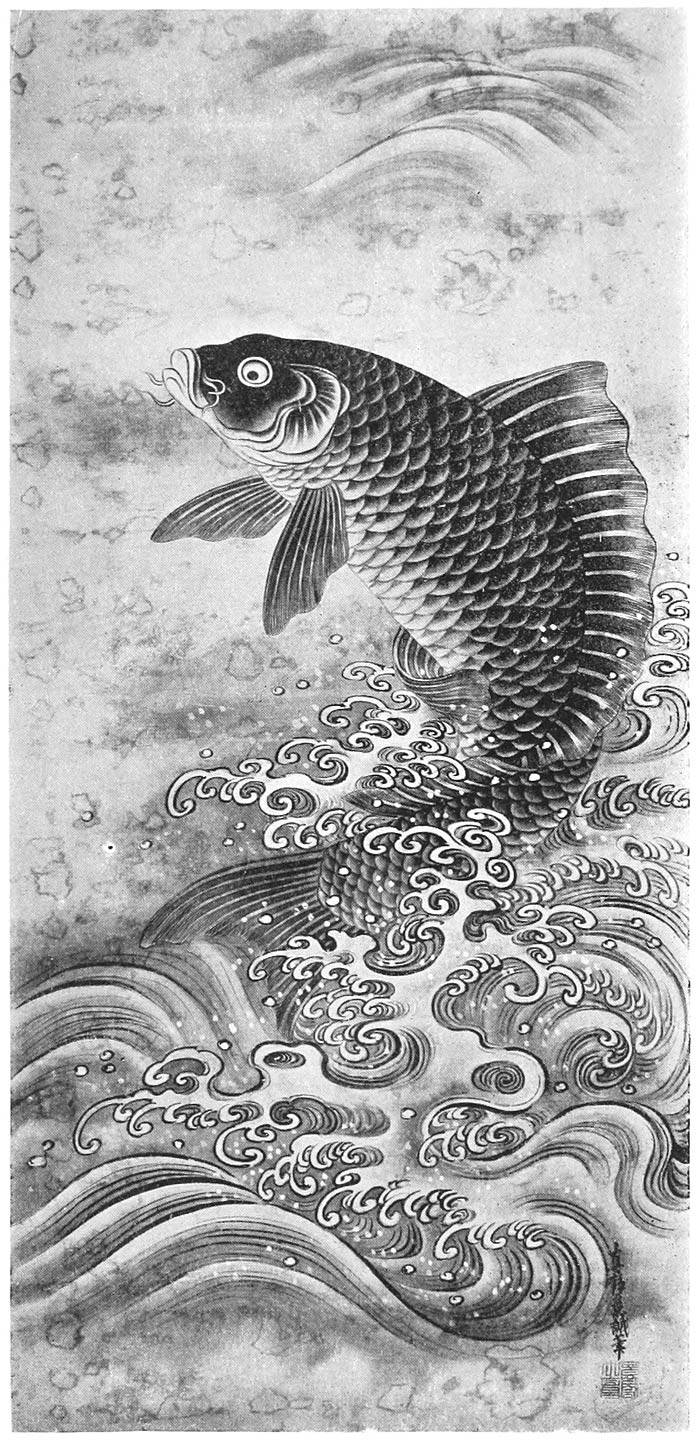

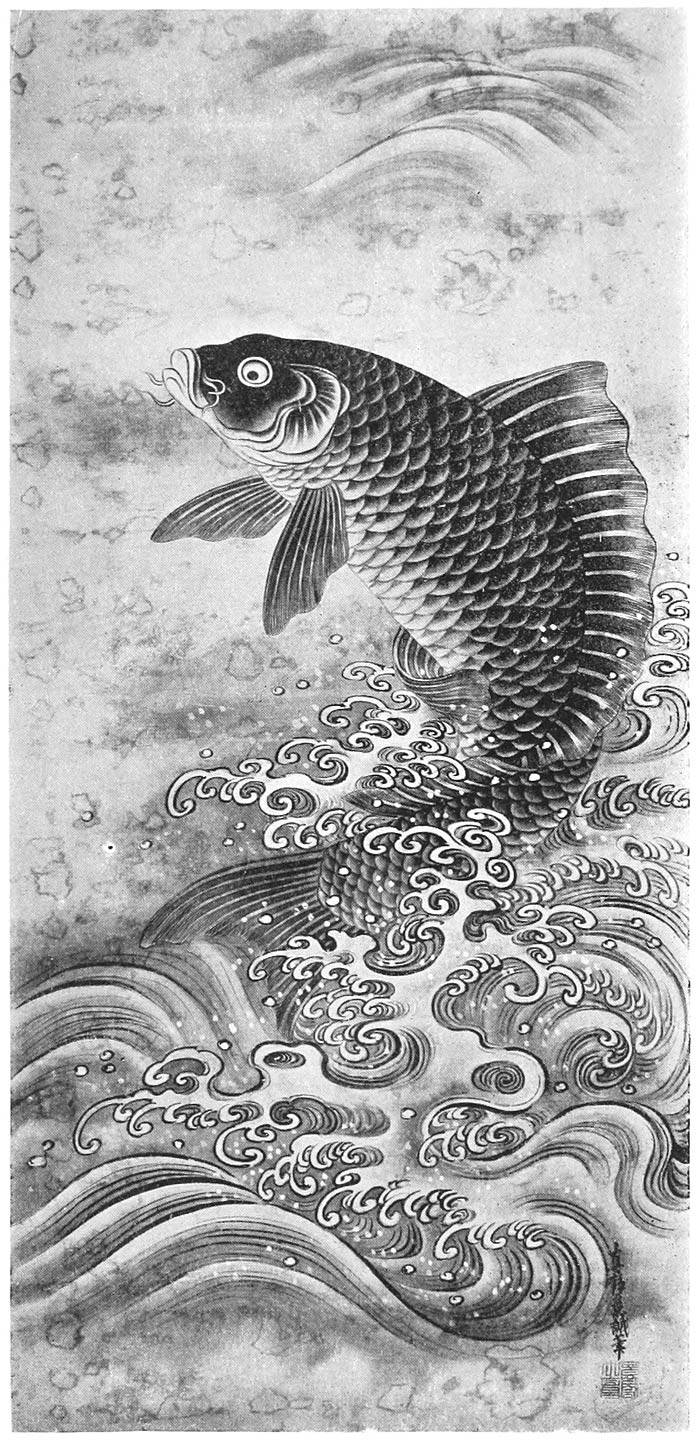

CARP LEAPING FROM WAVES

From a Japanese painting in the British Museum

Now it happened that the Emperor’s daughter—a very beautiful girl—was lying ill in the royal palace. The Court physicians had endeavoured in vain to restore her to health. Hearing of Wang Shuh’s discovery of the Red Cloud herb, the Emperor sent out for him. On reaching the palace, the herbalist was addressed by the Emperor himself, who said: “Is it true, as men tell, that you have seen the black kiao in the form of a little blue boy riding on a red carp?”

“It is indeed true,” Wang Shuh made answer.

“And is it true that you have found the dragon herb that sprang up during the thunder-storm?”

“I have brought the herb with me, Your Majesty.”

“Mayhap,” the Emperor said, “it will give healing to my daughter.”

Wang Shuh at once made offer of the herb, and the Emperor led him to the room in which the sick princess lay. The herb had a sweet odour,12 and Wang Shuh plucked a leaf and gave it to the lady to smell. She at once showed signs of reviving, and this was regarded as a good omen. Wang Shuh then made a medicine from the herb, and when the princess had partaken of it, she grew well and strong again.

The Emperor rewarded Wang Shuh by appointing him his chief physician. Thus the herbalist became a great and influential man.

To few mortals comes the privilege of setting eyes on a dragon, and to fewer is the vision followed by good fortune.

In this quaint story the Red Cloud herb is evidently a kupua of the thunder-dragon. It had “soul substance” (the vital essence). Another kupua or avatar was the carp.

In China and Japan there are references in dragon stories to pine trees being forms assumed by dragons. The connection between the tree and dragon is emphasized by the explanation that when a pine becomes very old it is covered with scales of bark, and ultimately changes into a dragon. By night “dragon lanterns” (ignis fatuus) are seen on pine trees in marshy places, and on the masts of ships at sea.

The pine trees at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines are said to be regularly illuminated by these “supernatural” lights. The “lanterns” are supposed to come from the sea. Japanese stories tell that when a lantern appears on a pine, a little boy, known as the “Heavenly Boy”, is to be seen sitting on the topmost branch. Some lights were supposed to be the souls of holy men. In Gaelic stories are told about little men being seen in these wandering lights.

There is an evil form of the fire which is supposed to rise from the blood of a suicide or of a murderer’s victim. The “heart fire” (the “vital spark”) in the blood is supposed to rise as a flame from the ground. A similar superstition prevailed in England. If lights made their appearance above a prison on the night before the arrival of the judges of assize, the omen was regarded as a fatal one for the prisoners. The belief is widespread in the British Isles that lights (usually greenish lights) appear before a sudden death takes place.

Wandering lights seen on mountains were supposed by the Chinese and Japanese to be caused by dragons. A Japanese legend associates them with a dragon woman, named Zennyo, who appears to have the attributes of a fire-goddess. It is told regarding a Buddhist priest who lived beside a dragon hole on Mount Murōbu. One day, as he was about to cross a river, a lady wearing rich and dazzling attire came up to him and made request for a magic charm he possessed. She spoke with averted face, telling who she was. The priest repeated the charm to her and then said: “Permit me to look upon your face”.

Said the dragon woman: “It is very terrible to behold. No man dare gaze on my face. But I cannot refuse your request.”

The priest had his curiosity satisfied, but apparently without coming to harm. Priestly prestige was maintained by stories of this kind.

As soon as the priest looked in her face the dragon woman rose in the air, and stretched out the small finger of her right hand. It was not, however, of human shape, but a claw that suddenly extended a great length and flashed lights of five colours. The “five colours” indicate that the woman was a deity. Kwan Chung, in his work Kwantsze, says: “A dragon in the water covers himself with five colours. Therefore, he is a god (shin).”13

The “fire nail” figures prominently in Polynesian mythology. In the legend of Maui, that hero-god goes to the old woman (the goddess), his grandmother, to obtain fire for mankind. “Then the aged woman pulled out her nail; and as she pulled it out fire flowed from it, and she gave it to him. And when Maui saw she had drawn out her nail to produce fire for him, he thought it a most wonderful thing.”14

The reference in the Japanese story to the averted face of the dragon woman may be connected with the ancient belief that the mortal who looked in the face of a deity was either shrivelled up or transformed into stone, as happened in the case of those who fixed their eyes upon the face of Medusa. Goddesses like the Egyptian Neith were “veiled”. A Japanese legend tells of a dragon woman who appeared as a woman with a malicious white face. She laughed loudly, displaying black teeth. She was often seen on a bridge, binding up her hair.15 Apparently she was a variety of the mermaid family, and this may explain the reference to her being “one legged”. The people scared her away by forming a torch-light procession and advancing towards her. Dragons were sometimes expelled by means of fire. In Europe, bonfires were lit when certain “ceremonies of riddance” were performed.

British mermaids are credited, in the folk-tales, with providing cures for various diseases, and especially herbs,16 and in this connection they link with the dragon wives of China and Japan. Some dragon women lived for a time among human beings as do swan-maidens, nereids, mermaids, and fairies in the stories of various lands.

A Japanese legend tells of an elderly and mysterious woman who had the power to cure any ill that flesh is heir to. When a patient called, she listened attentively to what was told her. Then she retired to a secret chamber, sat down and placed a rush mat17 on her head. After sitting alone for a time (apparently engaged in working a magic spell) she left the chamber and returned to the patient. She recommended the “faith cure”. Making the pretence that she was handing over a medicine, she said: “Believe that I have given you medicine. Now, go away. Each day you must sit down and imagine that you are taking my medicine. Come back to me in seven days’ time.” Those who faithfully carried out her instructions are said to have been cured. Large numbers visited her daily.

It was suspected that this woman was possessed by the spirit of a water-demon. A watch was set upon her, and one night she was seen going from her house to a well in which, during the day, she often washed her head while being consulted by patients. Those who watched her told that she remained in human shape for a little time. Then she transformed herself into a white mist and entered the well. Protective charms were recited, and she never returned. For many years afterwards, however, her house was haunted.

De Groot relates a story about one of the wives of an Emperor of China who practised magic by means of reptiles and insects. Her object was to have her son selected as crown prince. She was detected, and she and her son were imprisoned. Both became dragons before they died.

Dragons sometimes appear in the stories in the rôle of demon lovers. A Japanese legend tells of two boys who were the children of a man and a dragon woman. In time they changed into dragons and flew away. The woman herself came to her lover in the shape of a snake, and then transformed herself into a beautiful maiden.

This is a version of a very widespread story, found in the Old and New World, which was possibly distributed by ancient mariners and traders. Its most familiar form is the French legend of Melusina, the serpent woman, who became the wife of Raymond of Poitou, and the mother of his disfigured children.18

A Chinese legend of the Melusina order deals with the fall of the Hea Dynasty. A case of dragon foam which had been kept in the royal palace during three dynasties was one day opened, and there issued forth a dragon in the form of a black lizard. It touched a young virgin, who became the mother of a girl whom she bore in secret and abandoned in a wood. It chanced that a poor man and his wife, who were childless, hearing the cries of the babe, took her to their house, where they cared for her tenderly. But the magicians came to know of the dragon’s daughter, of whom it had been prophesied that she would destroy the dynasty. Search was made for the child, and the foster-parents fled with her to the land of Pao. They presented her to the king of the land, and she grew up to be a beautiful maid who was called Pao Sze. The king loved her dearly, and when she gave birth to a son, he made her his queen, degrading Queen Chen and her son, the crown prince. Poh Fuh, the son of the dragon woman, then became crown prince instead.

Now Pao Sze, although very beautiful, was always sad of countenance. She never smiled. The king did everything in his power to make her smile and laugh. But his efforts were in vain.

“Fain would I hear you laugh,” said he.

But she only sighed and said: “Ask me not to laugh.”

One day the king, in his endeavours to break the spell of sadness that bound his beautiful queen, arranged that his lords should enter the palace and declare that an enemy army was at hand, and that the life of the king was in peril.

This they did. The king was at the time making merry when his lords entered suddenly and said: “Your Majesty, the enemy have come, while you sit making merry, and they are resolved to slay you.”

The king’s sudden change of countenance made the dragon woman laugh. His Majesty was well pleased.

Then, as it chanced, the enemy came indeed. But when the alarm was raised, the lords thought it was a false one. The army took possession of the city, entered the palace, and slew the king. Pao Sze was taken prisoner, because of her fatal beauty; but she brought no joy to her captor and transformed herself into a dragon, departing suddenly and causing a thunder-storm to rage.

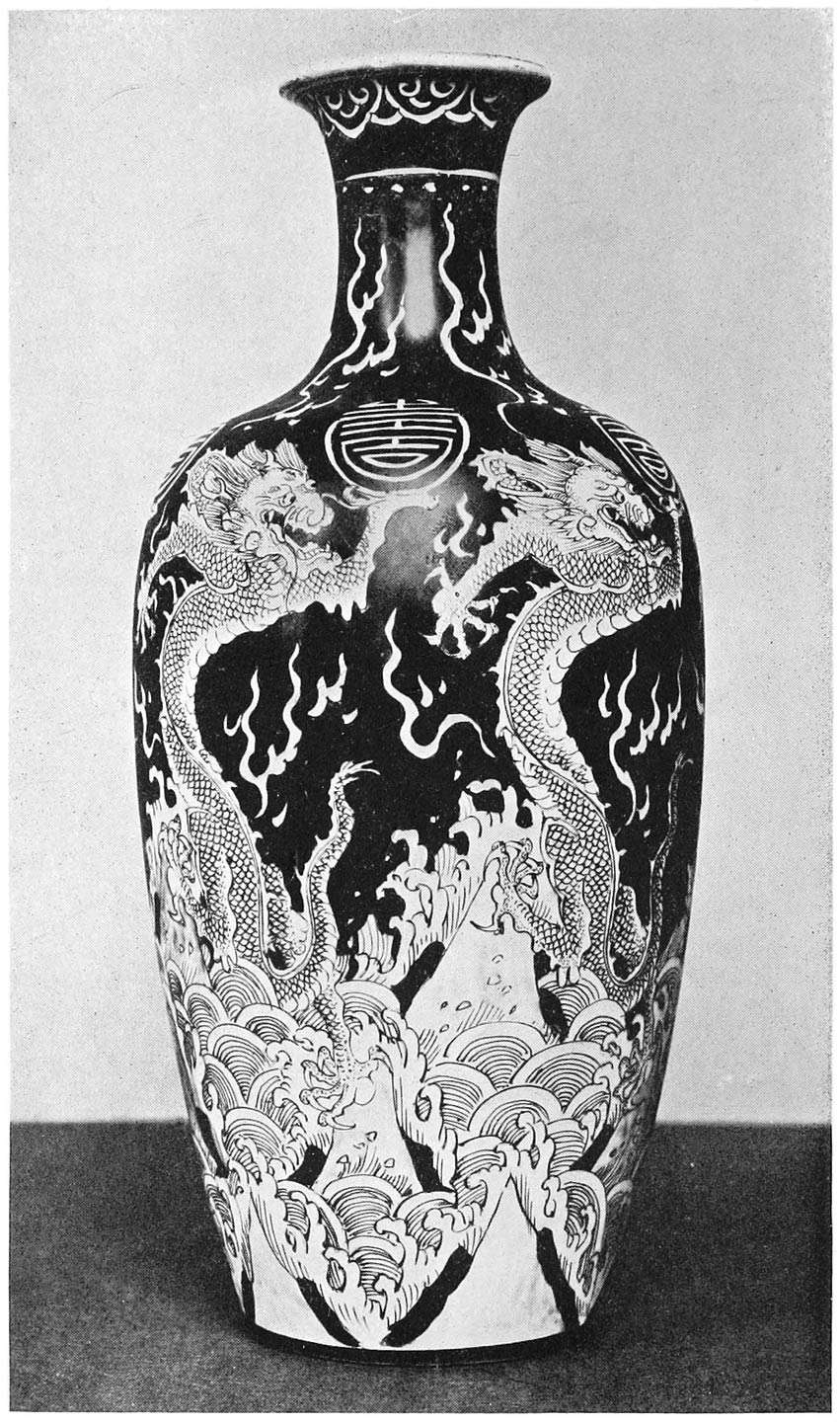

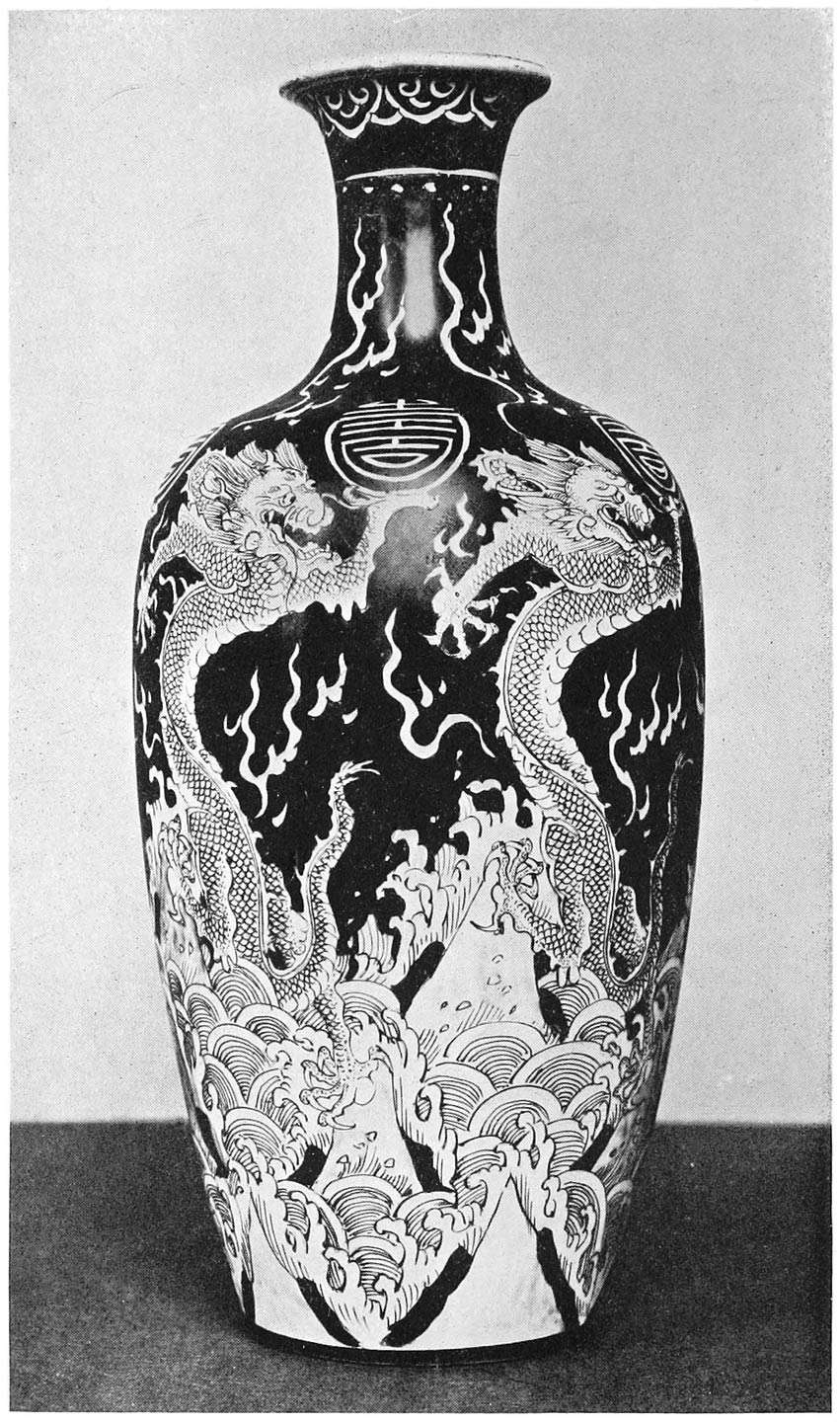

CHINESE PORCELAIN VASE DECORATED WITH FIVE-CLAWED DRAGONS RISING FROM WAVES

(Victoria and Albert Museum)

To those who win their favour, the dragons are preservers even when they come forth as destroyers. The story is told of how Wu, the son of a farmer named Yin, won the favour of a dragon and rose to be a great man in China. When he was a boy of thirteen, he was sitting one day at the garden gate, looking across the plain which is watered by a winding river that flows from the mountains. He was a silent, dreamy boy, who had been brought up by his grandmother, his mother having died when he was very young, and it was his habit thus to sit in silence, thinking and observing things. Along the highway came a handsome youth riding a white horse. He was clad in yellow garments and seemed to be of high birth. Four man-servants accompanied him, and one held an umbrella to shield him from the sun’s bright rays. The youth drew up his horse at the gate and, addressing Wu, said: “Son of Yin, I am weary. May I enter your father’s house and rest a little time?”

The boy bowed and said: “Enter.”

Yin then came forward and opened the gate. The noble youth dismounted and sat on a seat in the court, while his servants tethered the horse. The farmer chatted with his visitor, and Wu gazed at them in silence. Food was brought, and when the meal was finished, the youth thanked him for his hospitality and walked across the courtyard. Wu noticed that before one of the servants passed through the gate, he turned the umbrella upside down. When the youth had mounted his horse, he turned to the silent, observant boy and said: “I shall come again to-morrow.”

Wu bowed and answered: “Come!”

The strangers rode away, and Wu sat watching them until they had vanished from sight.

When evening came on, the farmer spoke to his son regarding the visitors, and said: “The noble youth knew my name and yet I have never set eyes on him before.”

Wu was silent for a time. Then he said: “I cannot say who the youth is or who his attendants are.”

“You watched them very closely, my son. Did you note anything peculiar about them?”

Said Wu: “There were no seams in their clothing; the white horse had spots of five colours and scaly armour instead of hair. The hoofs of the horse and the feet of the strangers did not touch the ground.”19

Yin rose up with agitation and exclaimed: “Then they are not human beings, but spirits.”

Said Wu: “I watched them as they went westward. Rain-clouds were gathering on the horizon, and when they were a great distance off they all rose in the air and vanished in the clouds.”20

Yin was greatly alarmed to hear this, and said: “I must ask your grandmother what she thinks of this strange happening.”

The old woman was fast asleep, and as she had grown very deaf it was difficult to awaken her. When at length she was thoroughly roused, and sat up with head and hands trembling with palsy,21 Yin repeated to her in a loud voice all that Wu had told him.

Said the woman: “The horse, spotted with five colours, and with scaly armour instead of hair, is a dragon-horse. When spirits appear before human beings they wear magic garments. That is why the clothing of your visitors had no seams. Spirits tread on air. As these spirits went westward, they rose higher and higher in the air, going towards the rain-clouds. The youth was the Yellow Dragon. He is to raise a storm, and as he had four followers, the storm will be a great one. May no evil befall us.”

Then Yin told the old woman that one of the strangers had turned the umbrella upside down before passing through the garden gate. “That is a good omen,” she said. Then she lay down and closed her eyes. “I have need of sleep,” she murmured; “I am very old.”22

Heavy masses of clouds were by this time gathering in the sky, and Yin decided to sit up all night. Wu asked to be permitted to do the same, and his father consented. Then the boy lit a yellow lantern, put on a yellow robe that his grandmother had made for him, burned incense, and sat down reading charms from an old yellow book.23

The storm burst forth in fury just when dawn was breaking dimly. Wu then closed his yellow book and went to a window. The thunder bellowed, the lightning flamed, and the rain fell in torrents, and swollen streams poured down from the mountains. Soon the river rose in flood and swept across the fields. Cattle gathered in groups on shrinking mounds that had become islands surrounded by raging water.

Yin feared greatly that the house would be swept away, and wished he had fled to the mountains.

At night the cottage was entirely surrounded by the flood. Trees were cast down and swept away. “We cannot escape now,” groaned Yin.

Wu sat in silence, displaying no signs of emotion. “What do you think of it all?” his father asked.

Wu reminded him that one of the strangers had turned the umbrella upside down, and added: “Before the dragon youth went away he spoke and said: ‘I shall come again to-morrow’.”

“He has come indeed,” Yin groaned, and covered his face with his hands.

Said Wu: “I have just seen the dragon. As I looked towards the sky he spread out his great hood above our home. He is protecting us now.”

“Alas! my son, you are dreaming.”

“Listen, father, no rain falls on the roof.”

Yin listened intently. Then he said: “You speak truly, my son. This is indeed a great marvel.”

“It was well,” said Wu, “that you welcomed the dragon yesterday.”

“He spoke to you first, my son; and you answered, ‘Enter’. Ah, you have much wisdom. You will become a great man.”

The storm began to subside, and Wu prevailed upon his father to lie down and sleep.24

Much damage had been done by storm and flood, and large numbers of human beings and domesticated animals had perished. In the village, which was situated at the mouth of the valley, only a few houses were left standing.

The rain ceased to fall at midday. Then the sun came out and shone brightly, while the waters began to retreat.

Wu went outside and sat at the garden gate, as was his custom. In time he saw the yellow youth returning from the west, accompanied by his four attendants. When he came nigh, Wu bowed and the youth drew up his horse and spoke, saying: “I said I should return to-day.”

Wu bowed.

“But this time I shall not enter the courtyard,” the youth added.

“As you will,” Wu said reverently.

The dragon youth then handed the boy a single scale which he had taken from the horse’s neck, and said: “Keep this and I shall remember you.”

Then he rode away and vanished from sight.

The boy re-entered the house. He awoke his father and said: “The storm is over and the dragon has returned to his pool.”25

Yin embraced his son, and together they went to inform the old woman. She awoke, sat up, and listened to all that was said to her. When she learned that the dragon youth had again appeared and had spoken to Wu, she asked: “Did he give you ought before he departed?”

Wu opened a small wooden box and showed her the scale that had been taken from the neck of the dragon horse.

The woman was well pleased, and said: “When the Emperor sends for you, all will be well.”

Yin was astonished to hear these words, and exclaimed: “Why should the Emperor send for my boy?”

“You shall see,” the old woman made answer as she lay down again.

Before long the Emperor heard of the great marvel that had been worked in the flooded valley. Men who had taken refuge on the mountains had observed that no rain fell on Yin’s house during the storm. So His Majesty sent couriers to the valley, and these bade Yin to accompany them to the palace, taking Wu with him.

On being brought before the Emperor, Yin related everything that had taken place. Then His Majesty asked to see the scale of the dragon horse.

It was growing dusk when Wu opened the box, and the scale shone so brightly that it illumined the throne-room so that it became as bright as at high noon.

Said the Emperor: “Wu shall remain here and become one of my magicians. The yellow dragon has imparted to him much power and wisdom.”

Thus it came about that Wu attained high rank in the kingdom. He found that great miracles could be worked with the scale of the dragon horse. It cured disease, and it caused the Emperor’s army to win victories. Withal, Wu was able to foretell events, and he became a renowned prophet and magician.

The farmer’s son grew to be very rich and powerful. A great house was erected for him close to the royal palace, and he took his grandmother and father to it, and there they lived happily until the end of their days.

Thus did Wu, son of Yin, become a great man, because of the favour shown to him by the thunder-dragon, who had wrought great destruction in the river valley and taken toll of many lives.

It will be gathered from this story that the Chinese dragon is not always a “beneficent deity”, as some writers put it. Like certain other gods, he is a destroyer and preserver in one.