CHAPTER VIII

THE KINGDOM UNDER THE SEA

The Vanishing Island of Far-Eastern Dragon-god—Story of Priest who visited Underworld—Far-Eastern Dragon as “Pearl Princess”—Her Human Lover—An Indian Parallel—Dragon Island in Ancient Egyptian Story—The Osirian Underworld—Vanishing Island in Scotland and Fiji—Babylonian Gem-tree Garden—Far-Eastern Quest of the Magic Sword—Parallels of Teutonic and Celtic Legend—“Kusanagi Sword”, the Japanese “Excalibur”—City of the Far-Eastern Sea-god—Japanese Vision of Gem-tree Garden—Weapon Demons—Star Spirits of Magic Swords—Swords that become Dragons—Dragon Jewels—Dragon Transformations.

The palace of the dragon king is situated in the Underworld, which can be entered through a deep mountain cave or a dragon-guarded well. In some of the Chinese stories the dragon palace is located right below a remote island in the Eastern Sea. This island is not easily approached, for on the calmest of days great billows dash against its shelving crags. When the tide is high, it is entirely covered by water and hidden from sight. Junks may then pass it or even sail over it, without their crews being aware that they are nigh to the palace of the sea-god.

Sometimes a red light burns above the island at night. It is seen many miles distant, and its vivid rays may be reflected in the heavens.

In a Japanese story the island is referred to as “a glowing red mass resembling the rising sun”. No mariner dares to approach it.

There was once a Chinese priest who, on a memorable night, reached the dragon king’s palace by entering a deep cave on a mountain-side. It was his pious desire to worship the dragon, and he went onward in the darkness, reciting religious texts that gave him protection. The way was long and dark and difficult, but at length, after travelling far, he saw a light in front of him. He walked towards this light and emerged from the cavern to find that he was in the Underworld. Above him was a clear blue firmament lit by the night sun. He beheld a beautiful palace in the midst of a garden that glittered with gems and flowers, and directed his steps towards it. He reached a window the curtain of which rustled in the wind. He perceived that it was a mass of gleaming pearls. Peering behind it, as it moved, he beheld a table formed of jewels. On this table lay a book of Buddhist prayers (sutras).

As he gazed with wonder and reverence, the priest heard a voice that spake and said: “Who hath come nigh and why hath he come?”

The priest answered in a low voice, giving his name, and expressing his desire to behold the dragon king, whom he desired to worship.

Then the voice made answer: “Here no human eye can look upon me. Return by the way thou hast come, and I shall appear before thee at a distance from the cavern mouth.”

The priest made obeisance, and returned to the world of men by the way he had come. He went to the spot that the voice had indicated, and there he waited, reading sacred texts. Soon the earth yawned and the dragon king arose in human shape, wearing a red hat and garment. The priest worshipped him, and then the dragon vanished from sight. On that sacred spot a temple was afterwards erected.

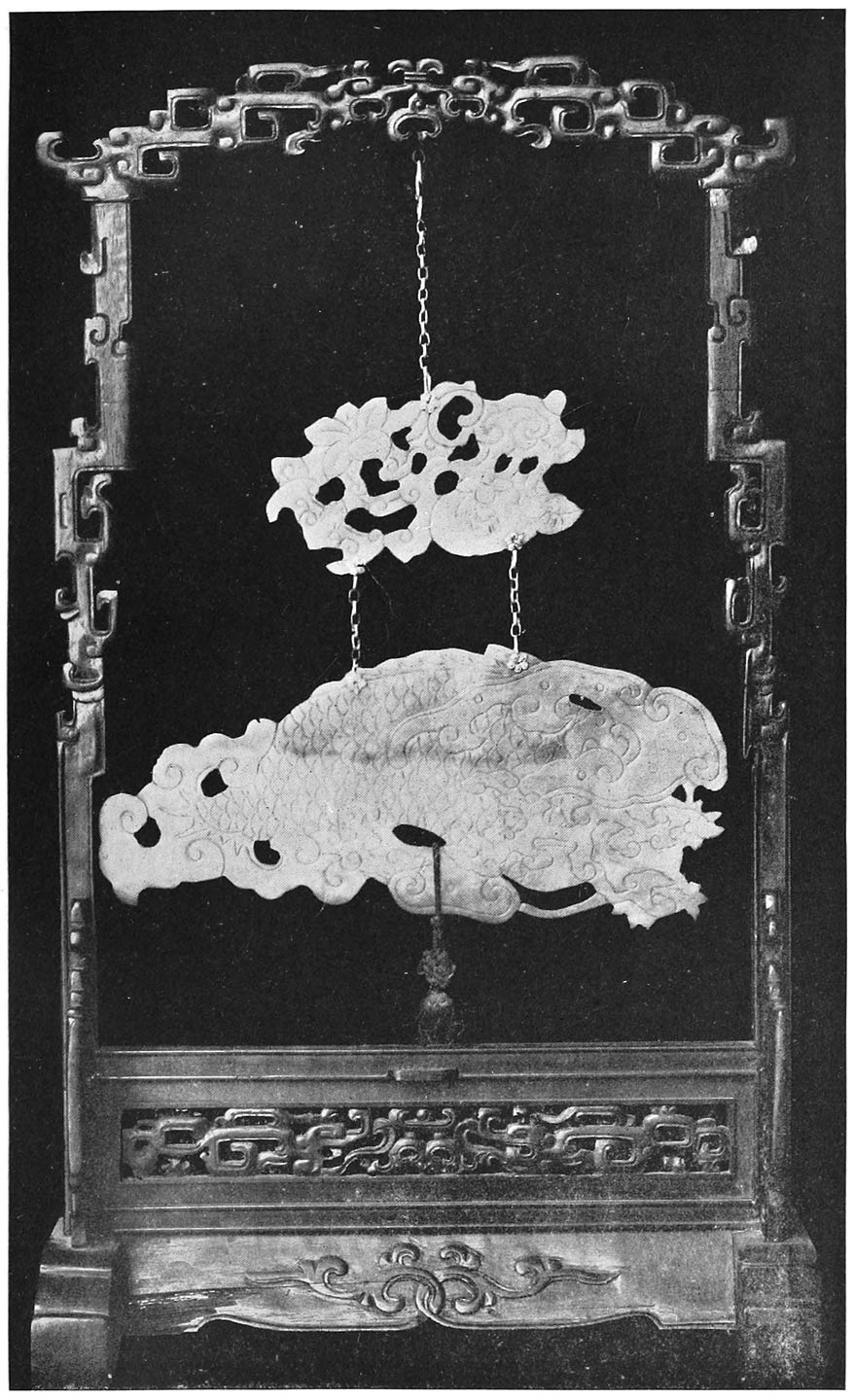

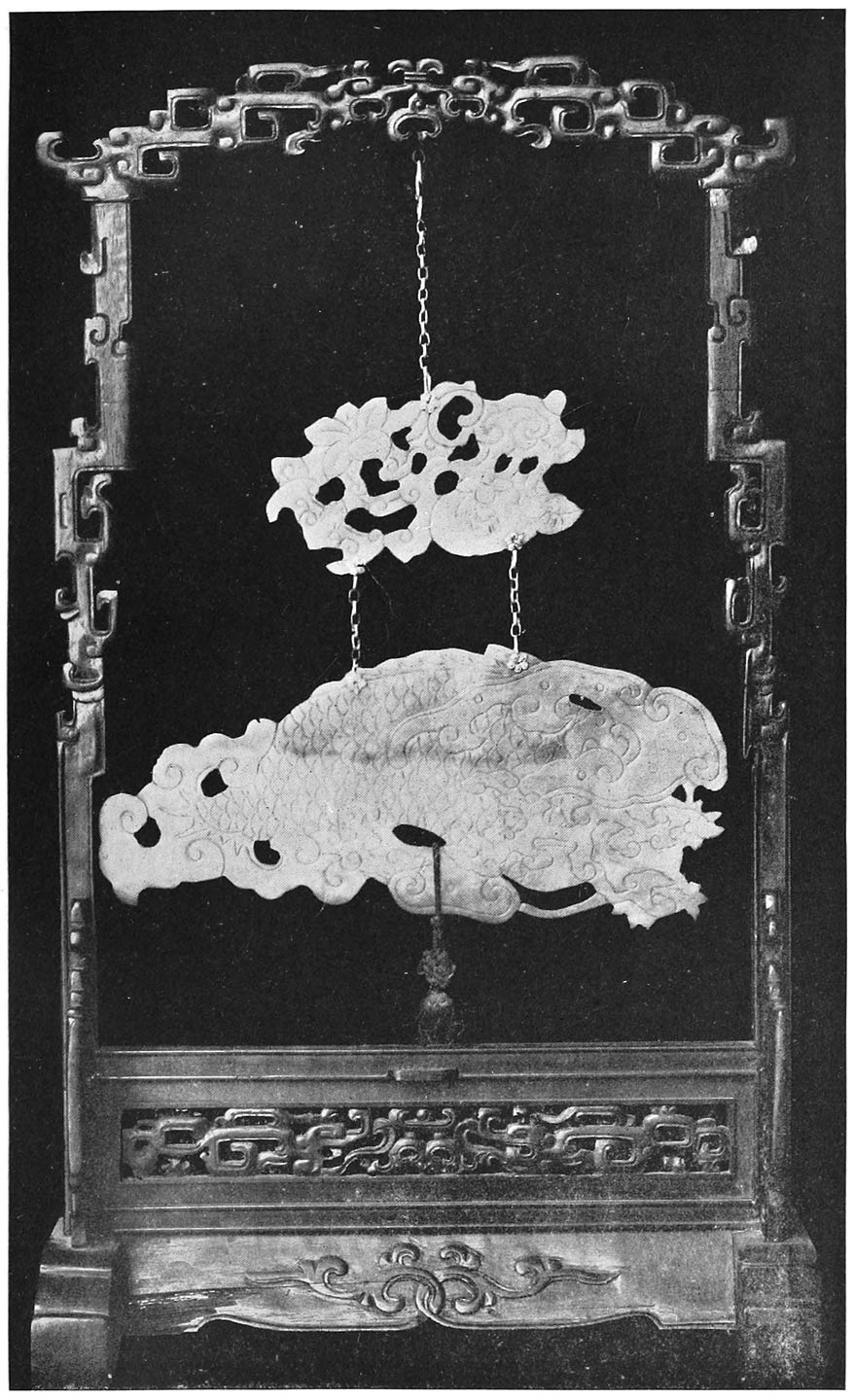

RESONANT STONE OF JADE SHOWING DRAGON WITH CLOUD ORNAMENTS, SUSPENDED FROM CARVED BLACKWOOD FRAME

A fine specimen of the glyptic art of the Kʼien-lung period. The symbols include the peach of longevity, the swashtika, the luck bat, the fungus of immortality, &c. These combined signify, “May numberless years and luck come to an end only at old age.”

By courtesy of B. Laufer, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago

Once upon a time the daughter of the dragon king, who was named “Abundant Pearl Princess”, fell in love with a comely youth of Japan. He was sitting, on a calm summer day, beneath a holy tree, and his image was reflected in a dragon well. The princess appeared before him and cast a love spell over his heart. The youth was enchanted by her beauty, and she led him towards the palace of the dragon king, the “Abundant Pearl Prince”. There she married him, and they lived together for three years. Then the youth was possessed by a desire to return to the world of men. In vain the princess pleaded with him to remain in the palace. When, however, she found that his heart was set on leaving the kingdom of the Underworld, she resolved to accompany him. He was conveyed across the sea on the back of a wani (a dragon in crocodile shape). The princess accompanied him, and he built a house for her on the seashore.

The “Abundant Pearl Princess” was about to become a mother, and she made the youth promise not to look upon her until after her child was born. But he broke his vow. Overcome with curiosity, he peered into her chamber and saw that his wife had assumed the shape of a dragon. As soon as the child was born, the princess departed in anger and was never again beheld by her husband.

This story, it will be noted, is another Far-Eastern version of the Melusina legend.

An Indian version of the tale relates that the hero was a sailor, the sole survivor from a wreck, who swam to a small island in the midst of the sea. When he reached the shore, he set out to look for food, but found that the trees and shrubs, which dazzled him with their beauty, bore beautiful gems instead of fruit. At length, however, he found a fruit-bearing tree. He ate and was well content. Then he sat down beside a well. As he stooped to drink of its waters, he had a vision of the Underworld in all its beauty. At the bottom of the well sat a fair sea-maid, who looked upwards with eyes of love and beckoned him towards her. He plunged into the well and found himself in the radiant Kingdom of Ocean. The maid was the queen, and she took him as her consort. She promised him great wealth, but forbade him to touch the statue of an Apsara1, which was of gold and adorned with gems. But one day he placed his hand on the right foot of the image. The foot darted forth and struck him with such force that he was driven through the sea and washed ashore on his native coast.2

The oldest version of this type of story comes from Egypt. It has been preserved in a papyrus in the Hermitage collection at Petrograd, and is usually referred to as of Twelfth Dynasty origin (c. 2000 B.C.). A sailor relates that he was the sole survivor from a wreck. He had seized a piece of wood and swam to an island. After he recovered from exhaustion, he set out to search for food. “I found there figs and grapes, all manner of good herbs, berries and grain, melons of all kinds, fishes and birds.” In time, he heard a noise “as of thunder”, while “the trees shook and the earth was moved”. The ruler of the island drew nigh. He was a human-headed serpent “thirty cubits long, and his beard greater than two cubits; his body was as overlaid with gold, and his colour as that of true lapis-lazuli”.

The story proceeds to tell that the sailor becomes the guest of the serpent, who makes speeches to him and introduces him to his family. It is stated that the island “has risen from the waves and will sink again”. After a time the sailor is rescued by a passing vessel.3 This ancient Egyptian tale links with the Indian and Chinese versions given above. The blue serpent resembles closely the Chinese dragon; the vanishing island is common to Egypt and China. Like much else that came from Egypt, the island has a history. Long before the ancient mariners transferred it to the ocean, it figured in the fused mythology of the Solar and Osirian cults. Horus hid from Set on a green floating island on the Nile. He was protected by a serpent deity. His father, Osiris, is Judge and Ruler of the Underworld, and has a serpent shape as the Nile god and the dragon of the abyss. The red light associated with the Chinese dragon island of ocean recalls the Red Horus, a form of the sun-god, rising from the Nile of the Underworld, on which floated the green nocturnal sun, “the green bed of Horus” and a form of his father Osiris as the solar deity of night.

The Osirian underworld idea appears to have given origin to the widespread stories found as far apart as Japan and the British Isles regarding “Land-under-Waves” and “the Kingdom of the Sea”. The green floating island of Paradise is referred to in Scottish Gaelic folk-tales. In Fiji the natives tell of a floating island that vanishes when men approach it.4

In some Chinese legends Egyptian conceptions blend with those of Babylonia. The Chinese priest who, in the dragon-king story, reached the Underworld through a deep cave, followed in the footsteps of Gilgamesh, who went in search of the “Plant of Life”—the herb that causes man “to renew his youth like the eagle”.5 Gilgamesh entered the cave of the Mountain of Mashi (Sunset Hill), and after passing through its night-black depths, reached the seaside garden in which, as on the island in the Indian story, the trees bore, instead of fruit and flowers, clusters of precious stones. He beheld in the midst of this garden of dazzling splendour the palace of Sabitu, the goddess, who instructed him how to reach the island on which lived his ancestor Pir-naphishtum (Ut-napishtim). Gilgamesh was originally a god, the earlier Gishbilgames of Sumerian texts.6

The Indian Hanuman (the monkey-god) similarly enters a deep cave when he goes forth as a spy to Lanka, the dwelling-place of Ravana, the demon who carried away Sita, wife of Rama, the hero of the Rámáyana. A similar story is told in the mythical history of Alexander the Great. There are also western European legends of like character. Hercules searches for the golden apples that grow in the Hesperian gardens.7 In some Far Eastern stories the hero searches for a sword instead of an herb. “Every weapon,” declares an old Gaelic saying, “has its demon.” The same belief prevailed in China, where dragons sometimes appeared in the form of weapons, and in India, where the spirits of celestial weapons appeared before heroes like Arjuna and Rama.8 In the Teutonic Balder story, as related by Saxo Grammaticus,9 the hero is slain by a sword taken from the Underworld, where it was kept by Miming (Mimer), the god, in an Underworld cave. Hother, who gains possession of it, goes by a road “hard for mortal man to travel”.

In the Norse version the sword becomes an herb—the mistletoe, a “cure-all”, like the Chinese dragon herb and the Babylonian “Plant of Life”. Excalibur, the sword of King Arthur, was obtained from the lake-goddess (a British “Naga”), and was flung back into the lake before he died:

So flashed and fell the brand Excalibur:

But ere he dipped the surface, rose an arm

Clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful,

And caught him by the hilt, and brandished him

Three times, and drew him under in the mere.10

The Japanese story of the famous Kusanagi sword is a Far-Eastern link between the Celestial herb- and weapon-legends of Asia and Europe. It tells that this magic sword was one of the three treasures possessed by the imperial family of Japan, and that the warrior who wielded it could put to flight an entire army. At a naval battle the sword was worn by the boy-Emperor, Antoku Tennō. He was unable to make use of it, and when the enemy were seen to be victorious, the boy’s grandmother, Nu-no-ama, clutched him in her arms and leapt into the sea.

Many long years afterwards, when the Emperor Go Shirakawa sat on the imperial throne, his barbarian enemies declared war against him. The Emperor arose in his wrath and called for the Kusanagi sword. Search was made for it in the temple of Kamo, where it was supposed to be in safe-keeping. The Emperor was told, however, that it had been lost, and he gave orders that ceremonies should be performed with purpose to discover where the sword was, and how it might be restored. One night, soon afterwards, the Emperor dreamed a dream, in which a royal lady, who had been dead for centuries, appeared before him and told that the Kusanagi sword was in the keeping of the dragon king in his palace at the bottom of the sea.

Next morning the Emperor related his dream to his chief minister, and bade him hasten to the two female divers, Oimatsu and her daughter Wakamatsu, who resided at Dan-no-ura, so that they might dive to the bottom of the sea and obtain the sword.

The divers undertook the task, and were conveyed in a boat to that part of the ocean where the boy-Emperor, Antoku Tennō, had been drowned. A religious ceremony was performed, and the mother and daughter then dived into the sea. A whole day passed before they appeared again. They told, as soon as they were taken into the boat, that they had visited a wonderful city at the bottom of the sea. Its gates were guarded by silent sentinels who drew flashing swords when they (the divers) attempted to enter. They were consequently compelled to wait for several hours, until a holy man appeared and asked them what they sought. When they had informed him that they were searching for the Kusanagi sword, he said that the city could not be entered without the aid of Buddha.

Said the Emperor’s chief minister: “The city is that of the god of the sea.”

“It is very beautiful,” Oimatsu told him; “the walls are of gold, and the gates of pearl. Above the city walls are seen many-coloured towers that gleam like to precious stones. When one of the gates was opened, we perceived that the streets were of silver and the houses of mother-of-pearl.”

Said the Emperor’s chief minister: “Fain would I visit that city.”

He looked over the side of the boat and sighed, “I see naught but darkness.”

“When we dived and reached the sea-bottom,” Oimatsu continued, “we beheld a cave and entered it. Thick darkness prevailed, but we walked on and on, groping as we went, until we reached a beautiful plain over which bends the sky, blue as sapphire. Trees growing on the plain bear clusters of dazzling gems that sparkle among their leaves.”

“Were you not tempted to pluck them?” asked the minister.

“Each tree is guarded by a poisonous snake,” Oimatsu told him, “and we dared not touch the gems.”

On the following day the divers were provided with sutra-charms by the chief priest of the temple of Kamo.

They entered the sea again, and told, on their return next morning, that they had visited the city, and reached the palace of the dragon king, which was guarded by invisible sentries. Two women came out of the palace and bade them stand below an old pine tree, the bark of which glittered like the scales of a dragon. In front of them was a window. The blind was made of beautiful pearls, and was raised high enough to permit them to see right into the room.

One of the palace ladies said, “Look through the window.”

The women looked. In the room they saw a mighty serpent with a sword in his mouth. He had eyes bright as the sun, and a blood-red tongue. In his coils lay a little boy fast asleep.11 The serpent looked round and, addressing the women, spoke and said: “You have come hither to obtain the Kusanagi sword, but I shall keep it for ever. It does not belong to the Emperor of Japan. Many years ago it was taken from this palace by a dragon prince who went to dwell in the river Hi. He was slain by a hero of Japan.12 This hero carried off the sword and presented it to the Emperor. After many years had gone past a sea-dragon took the form of a princess. She became the bride of a prince of Japan, and was the grandmother of the boy-Emperor with whom she leapt into the sea during the battle of Dan-no-ura. This boy now lies asleep in my coils.”

The Emperor of Japan sorrowed greatly when he was informed regarding the dragon king’s message. “Alas!” he said, “if the Kusanagi sword cannot be obtained, the barbarians will defeat my army in battle.”

Then a magician told the Emperor that he knew of a powerful spell that would compel the dragon to give up the sword. “If it is successful,” the Emperor said, “I shall elevate you to the rank of a prince.”

The spell was worked, and when next the female divers went to the Kingdom under the Sea, they obtained the sword, with which they returned to the Emperor. He used it in battle and won a great victory.

The sword was afterwards placed in a box and deposited in the temple of Atsuta, and there it remained for many years, until a Korean priest carried it away. When, however, the Korean was crossing the ocean to his own land, a great storm arose. The captain of the vessel knew it was no ordinary storm, but one that had been raised by a god, and he spoke and said, “Who on board this ship has offended the dragon king of Ocean?”

Then said the Korean priest, “I shall throw my sword into the sea as a peace-offering.”

He did as he said he would, and immediately the storm passed away.

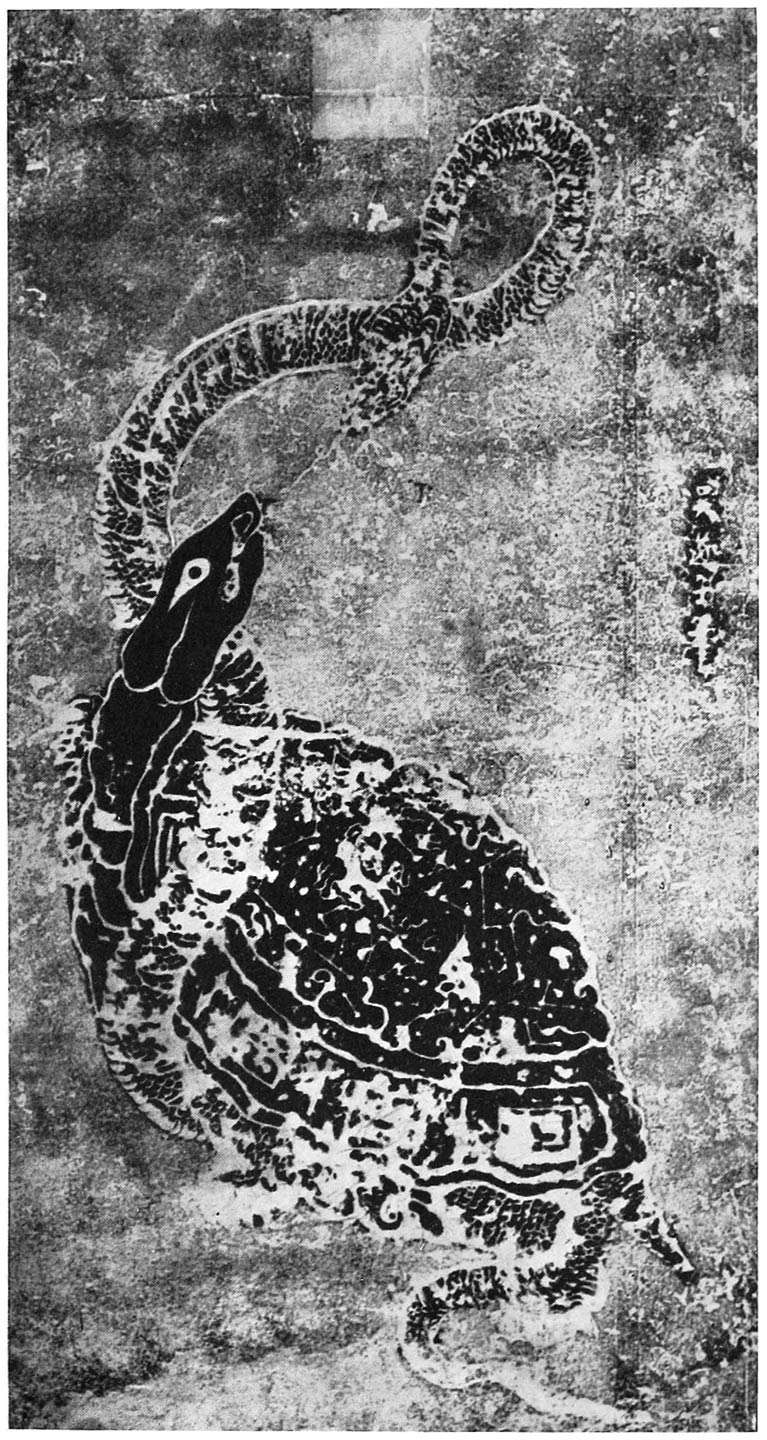

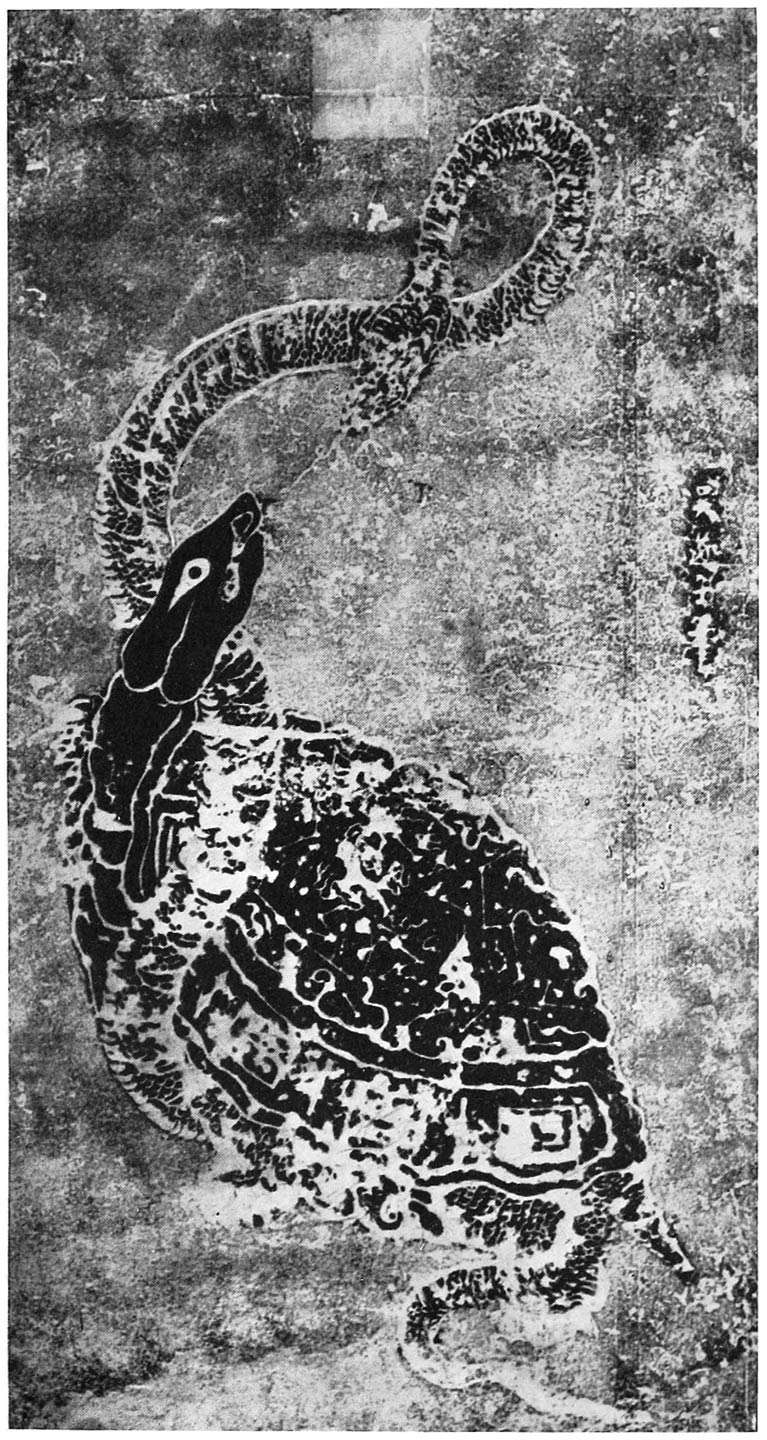

TORTOISE AND SNAKE

From a rubbing in the British Museum of a Chinese original

The dragon king caused the sword to be replaced in the temple from which the Korean had stolen it. There it lay for a century. Then it was carried back to the palace of the dragon-god in his Kingdom under the Sea.

Magic or supernatural swords were possessed by the spirits of dragon-gods.

According to a Chinese story in the Books of the Tsin Dynasty, an astrologer once discovered that among the stars there shone the spirits of two magic swords, and that they were situated right above the spot where the swords had, in time past, been concealed. Search was made for these, and deep down in the earth was found a luminous stone chest. Inside the chest lay two swords that bore inscriptions indicating that they were dragon swords. As soon as they were taken out of the box, their star-spirits faded from the sky.

These dragon swords could not be retained by human beings for any prolonged period. Stories are told of swords being taken away by spirit-beings and even of swords leaping of their own accord from their sheaths into rivers or the ocean, and assuming dragon shape as soon as they touched water.13

Similarly dragon jewels might be carried away by dragons who appeared in human shape—either as beautiful girls or as crafty old men.

It was fortunate for mortals when dragons appeared as human beings, as animals, or as fish that spoke with human voices. Dragons were unable to change their shapes when angry, or when they intended to avenge a wrong. A transformed dragon was therefore quite harmless.