CHAPTER XIV

CREATION MYTHS AND THE GOD AND GODDESS CULTS

Are Animistic Beliefs Primitive?—Evidence of a Mummy-imported Culture in Primitive Communities—Chinese Creation Myth—Chaos Transformed into Kosmos—Pʼan Ku as the World-artisan—Chinese World-giant Myth—Tibetan Version—Pʼan Ku and the Egyptian Ptah—Hammer Gods—Pʼan Ku and the Scandinavian Ymir—Osiris as a World-giant—Fusion of Egyptian and Babylonian Myths—The Chinese Ishtars—The Goddess of the Deluge—The Chinese Virgin Mother—Dragon Boat Ceremonies—The Mountain Goddess in China—Kiang Yuan as the Divine Mother—Ancient Myths in Chinese Buddhism—The “Poosa” as Goddess of Mercy—As Controller of Tides—Vision of Sky-goddess—Island Seat of Goddess Worship—The Chinese Indra.

Although some exponents of the stratification theory incline to regard Chinese religion as a stunted outcrop of animistic ideas, and chiefly because of the remarkable persistence through the ages of the worship of ancestors—the worship of ghost-gods and ghosts identified with gods—there is really little trace of what is usually referred to as “the primitive state of mind”. Under the term “animism” have been included ideas that are less primitive than was supposed to be the case about a generation ago. The belief, for instance, that there are spirits in stones, or that the soul of the dead enters a megalithic monument, or a statue placed in the tomb, may not, after all, belong to a primitive stage of thought; nor does it follow that because it is found to be prevalent among savage tribes isolated on lonely islands it is a product merely of the early “workings of the human mind” when man, as if by instinct, framed his “first crude philosophy of human thought”. The fact that savages reached isolated islands, such as, for instance, Eastern Island, where stone idols were erected, indicates clearly that they had acquired a knowledge of shipbuilding and navigation directly or indirectly from a centre of ancient civilization. It may be, therefore, that they likewise acquired from the same source ideas regarding the soul and the origin of things, and that these, instead of being “simple” and “primitive”, are really of complex character, and have remained in a state of arrested development, simply because they have been detached from the parent stem, to be preserved like flower petals pressed in a book, that still retain a degree of their original brightness and characteristic odour.

In outlying areas, like Australia and Oceania, are found not only “primitive beliefs”, but definite burial customs that have a long history elsewhere, including cremation and even mummification. “You get the whole bag of tricks in Australia”, the late Andrew Lang once declared to the writer when contending that certain beliefs and customs found in Egypt, Babylonia, India, and Europe were “natural products of the primitive mind”. But is it likely that such a custom as mummification should have “arisen independently” in Australasia? Let us take, for instance, the case of the mummy from the Torres Straits, which is preserved in the Mackay Museum in the University of Sydney. It was examined by Professor G. Elliot Smith, who, during his ten years’ occupancy of the Chair of Anatomy in the Government School of Medicine in Cairo, had unique opportunities of studying Ancient Egyptian surgery as revealed by the mummies preserved in Gizeh museum. When he examined the Papuan mummy at Sydney he found that undeniable Egyptian methods of a definite period in Egyptian history had been employed. He communicated his discovery to the Anthropological Section of the British Association in Melbourne in 1914, and, as an anatomist, was astonished to hear Professor Myres contending that it seemed to him natural that people should want to preserve their dead! “If”, Professor Elliot Smith has written, “Professor Myers had known anything of the history of anatomy he would have realized that the problem of preserving the body was one of extreme difficulty which for long ages had exercised the most civilized peoples, not only of antiquity, but also of modern times. In Egypt, where the natural conditions favouring the successful issue of attempts to preserve the body were largely responsible for the possibility of such embalming, it took more than seventeen centuries of constant practice and experimentation to reach the stage and to acquire the methods exemplified in the Torres Straits mummies.”1 Arm-chair theories vanish like mist when the light of scientific evidence is released.

In like manner may be found in the folk-lore and religious literature of China “mummies” of imported myths, as well as early myths of local invention that, ancient as they may be, cannot be regarded as “primitive” in the real sense of the term. The following myth, found in the literature of Taoism, may be more archaic than the writings of Kwang-tze, who gives it.

At the beginning of time there were two oceans—one in the south and one in the north, and there was land in the centre. The Ruler of the southern ocean was Shu (Heedless), and the Ruler of the northern ocean was Hu (Hasty), while the Ruler of the Centre was Hwun-tun (Chaos).

“Heedless” and “Hasty” were in the habit of paying regular visits to the land, and there they met and became acquainted. “Chaos” treated them kindly, and it was their desire to confer upon him some favour so as to give practical expression to their feelings of gratitude. They discussed the matter together, and decided what they should do.

Now Chaos was blind, his eyes being closed, and he was deaf, his ears being closed, and he could not breathe, having no nostrils, nor eat, because he was mouthless.

“Hasty” and “Heedless” met daily in the Central land, and each day they opened an orifice. On the seventh day their work was finished. But when he had eyes and ears opened, and could see and hear, and could breathe through his nostrils, and had a mouth with which to eat, old Chaos died.

The meaning of this Chinese parable seems to be that the Universe had, in the space of seven days, been “set in order”, Chaos having been transformed into Kosmos.

Although Taoism has been referred to by some writers of the “Evolution School” as “an elaboration of animistic lore”, this myth is really a product of the years that bring the philosophic mind. The three “Rulers” may have originally been giants, and the story may owe something to the Babylonian myth of Ea-Oannes, the sea-god, who came daily from the Persian Gulf to instruct the early Sumerians how to live civilized lives; but it was evidently some Far Eastern Socrates who first named the sea-gods “Heedless” and “Hasty”, and tinged the fable with Taoistic cynicism.

Creation myths are not as “primitive” as some writers would have us suppose. Considerable progress was achieved before mankind began to theorize regarding the origin of things. Even the widespread and so-called “primitive myth” about the egg from which the Universe, or the first god, was hatched by the “Primeval Goose” may belong to a much later stage of human development than is supposed by some of those writers who speculate with so much confidence regarding “the workings of the human mind”. Even the metaphysicians of Brahmanic India were prone to speak in parables and fables.

“At the beginning there was nothing”, the Chinese philosophers taught their pupils. “Long ages passed by. Then nothing became something.” The something had unity. Long ages passed by, and the something divided itself into two parts—a male part and a female part. These two somethings produced two lesser somethings, and the two pairs, working together, produced the first being, who was named Pʼan Ku. Another version of the myth is that Pʼan Ku emerged from the cosmic egg.

It is not difficult to recognize in Pʼan Ku a giant god or world-god. He was furnished with an adze, or, as is found in some Chinese prints, with a hammer and a chisel. With his implement or implements Pʼan Ku moves through the universe as the Divine Artisan, who shapes the mountains and hammers or chisels out the sky, accompanied by the primeval Tortoise, and the Phœnix, and a dragon-like being who may represent the primeval “somethings”—the symbols of water, earth, and air. The sun, moon, and stars have already appeared.

Another version of the Pʼan Ku myth represents him as the Primeval World-giant, who is destroyed so that the material universe may be formed. From his flesh comes the soil, from his bones the rocks; his blood is the waters of rivers and the ocean; his hair is vegetation; while the wind is his breath, the thunder his voice, the rain his sweat, the dew his tears, the firmament his skull, his right eye the moon, and his left eye the sun. Pʼan Ku’s body was covered with vermin, and the vermin became the races of mankind.

A somewhat similar myth is found in Tibet. When M. Huc sojourned in that country, he had a conversation with an aged nomad, who said:

“There are on the earth three great families, and we are all of the great Tibetan family. This is what I have heard the Lamas say, who have studied the things of antiquity. At the beginning there was on the earth only a single man; he had neither house nor tent, for at that time the winter was not cold, and the summer was not hot; the wind did not blow so violently, and there fell neither snow nor rain; the tea grew of itself on the mountains, and the flocks had nothing to fear from beasts of prey. This man had three children, who lived a long time with him, nourishing themselves on milk and fruits. After having attained to a great age, this man died. The three children deliberated what they should do with the body of their father, and they could not agree about it; one wished to put him in a coffin, the other wanted to burn him, the third thought it would be best to expose the body on the summit of a mountain. They resolved then to divide it into three parts. The eldest had the body and arms; he was the ancestor of the great Chinese family, and that is why his descendants have become celebrated in arts and industry, and are remarkable for their tricks and stratagems. The second son had the breast; he was the father of the Tibetan family, and they are full of heart and courage, and do not fear death. From the third, who had inferior parts of the body, are descended the Tartars, who are simple and timid, without head or heart, and who know nothing but how to keep themselves firm in their saddles.”2

Pʼan Ku, with his implements, links with the Egyptian artificer god Ptah of Memphis, who used his hammer to beat out the metal firmament. Ptah’s name means “to open” in the sense of “to engrave, to carve, to chisel”; the sun and moon were his eyes; he was “the great artificer in metals, and he was at once smelter, and caster, and sculptor, as well as the master architect and designer of everything that exists in the world”. In the Book of the Dead he (or Shu) is said to have performed “the ceremony of opening the mouth of the gods with an iron knife”,3 as “Hasty” and “Heedless” opened the mouth, eyes, ears, and nostrils of Chaos in the Chinese myth. The high priest of Memphis was called Ur Kherp hem, “the great chief of the hammer”. As we have seen, he was closely associated with the Egyptian potter’s wheel, which reached China at an early period. Like Ptah, Pʼan Ku is sometimes depicted as a dwarf, and sometimes as a giant.

Other hammer-gods include the Aryo-Indian Indra, who builds the world house; the Anatolian Tarku, the Mesopotamian Rammon or Adad, the northern European Thor. The hammer is apparently identical with adze and axe, and in Egypt the axe is an exceedingly ancient symbol of a deity; in Crete the double axe has a similar significance. In Scotland the hammer is carried by the Cailleach (Old Wife) in her character as Queen of Winter; she shapes the mountains with it, and causes the ground to freeze hard when she beats it. The hammer-god is in many countries a thunderer; to the modern Greeks lightning flashes are caused by blows of the “sky-axe” (astro-peléki); in Scottish Gaelic mention is made of the “thunder-ball” (peleir-tarnainach). A thunder-ball is carried by the Japanese thunder-god, but it is often replaced by the thunder-drum.

Pʼan Ku plays no conspicuous part in Chinese mythology; he is evidently an importation. In his character as a world-god he resembles the primeval giant Ymir of Norse-Icelandic myth, who was similarly cut up or ground in the “World Mill”, so that the universe might be set in order.

From the flesh of Ymir the world was formed,

From his blood the billows of the sea,

The hills from his bones, the trees from his hair,

The sphere of heaven from his skull.

Out of his brows the blithe powers made

Midgarth for sons of men,

And out of his brains were the angry clouds

All shaped above in the sky.4

Ymir was, like Pʼan Ku, born from inanimate matter. He was nourished by Audhumbla (Darkness and Vacuity), the cow mother, the Scandinavian Hathor.

From stormy billow sprang poison drops,

Which waxed into Jotum (giant) form,

And from him are come the whole of our Kin;

All fierce and dread is that race.5

Another version of the Ymir myth makes the giant come into existence like the self-created Ptah:

’Twas the earliest of times when Ymir lived;

Then was sand, nor sea, nor cooling wave,

Nor was Earth found even, nor Heavens on high;

There was Yawning of Deeps, and nowhere grass.6

The black dwarfs were parasites on Ymir’s body, as human beings were parasites on the body of Pʼan Ku.

It may be that the idea of a primeval giant like Pʼan Ku, or Ymir, was derived from the conception of Osiris as a world-god, which obtained in Egypt as far back as the Empire period. Erman translates a hymn in which it is said of the god: “The soil is on thy arm, its corners are upon thee as far as the four pillars of the sky. When thou movest, the earth trembles.…7 The Nile comes from the sweat of thy hands. Thou spewest out the wind that is in thy throat into the nostrils of men, and that whereon men live is divine. It is8 [alike in] in thy nostrils, the tree and its verdure, reeds, plants, barley, wheat, and the tree of life.” Everything constructed on earth lies on the “back” of Osiris. “Thou art the father and mother of men, they live on thy breath, they eat of the flesh of thy body. The ‘Primæval’ is thy name.”9

The body of Osiris was cut into pieces by Set. As the bones of Pʼan Ku and Ymir are the rocks, so are the bones of Set the iron found in the earth, but no myth survives of the cutting up of Set’s body. The black soil on the Nile banks is the body of Osiris, and vegetation springs from it.

It may be, however, that it was in consequence of the fusion in some cultural centre of the Babylonian myth regarding the cutting up of the dragon Tiamat and the cutting up of the body of Osiris that the northern Europeans came to hear of an Ymir and the Chinese of a Pʼan Ku from the early traders in amber, jade, and metals.

When Tiamat was slain, Marduk “smashed her skull”.

He cut the channels of her blood,

He made the North Wind bear it away into secret places.…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

He split her up like a flat fish into two halves,

One half of her he set in place as a covering for the heavens.

With the other part of Tiamat’s body Marduk made the earth. Then he fashioned the abode of the god Ea in the deep, the abode of the god Anu in high heaven, and the abode of Enlil in the air.10

In India is found another myth that appears to have contributed to the Chinese mosaic. At the beginning the Universal Soul assumed “the shape of a man”. This was Purusha.

“He did not feel delight. Therefore nobody, when alone, feels delight. He was desirous of a second. He was in the same state as husband (Pati) and wife (Patni).… He divided this self two fold. Hence were husband and wife produced. Therefore was this only a half of himself, as a split pea is of the whole.… The void was completed by woman.”11

It may be that India and China derived the god-splitting idea from a common source in Central Asia, where such “culture-mixing” appears to have taken place.

In China itself there are many traces of blended ideas. In the Texts of Confucianism, for instance, the symbol of the Khien stands for heaven, and that of the Khwan for earth.

In one of the native treatises it is stated:

“Khien suggests the idea of heaven; of a circle; of a ruler; of a father; of jade; of metal; of cold; of ice; of deep red; of a good horse; of an old horse; of a thin horse; of a piebald horse; and of the fruit of trees.

“Khwan suggests the idea of the earth; of a mother; of cloth; of a caldron; of parsimony; of a turning lathe; of a young heifer; of a large waggon; of what is variegated; of a multitude; and of a handle and support. Among soils it denotes what is black.”12

Here we have the Great Father, the god of heaven, who is red and is a circle (the sun); and the Great Mother, the goddess of Earth, who is black.

The sky-god is connected with jade and metal. As we have seen, the cult of the west attributed the creation of jade to the Chinese Ishtar. Precious metals were in several countries associated with sun, moon, and stars. The horse is one of the animals associated with sky-gods; it was, of course, later than the bull, stag, antelope, goat, ram, &c. Cold as well as warmth was sent by the sky-god, who controls the seasons.

The mother-goddess is the Caldron—the “Pot”, which, as has already been noted, was in Ancient Egypt the symbol of the inexhaustible womb of nature personified by deities like Hathor, Rhea, Aphrodite, Hera, Ishtar, &c. The “young heifer” has a similar connection, while the “waggon” seems to be another form of the “Pot”. Cloth was woven by men and women, but the production of thread was always the work of women in Ancient Egypt and elsewhere. Apparently the turning lathe was female, because the chisel was male; it may be that it was because the potter’s wheel was female that it had to be operated by a man. “A multitude” may refer to the reproductivity of the Great Mother of all mankind. The goddess was, perhaps, parsimonious because during a period of the year the earth gives forth naught, and stores all it receives.

The egg from which Pʼan Ku emerged appears to have been a symbol of the Mother Goddess of the sacred West, remembered in Chinese legends as Si Wang Mu, “the mother of the Western King”, and in Japanese as Seiobo, who was guardian of the World Tree, the giant peach, or the lunar, cassia tree (Chapter X). Other references to her, under various names, are scattered through ancient Chinese writings. In the “Annals of the Bamboo Books” mention is made of “the Heavenly lady Pa”. She favoured the Chinese monarch, Hwang Ti, who is supposed to have reigned during 2688 B.C. by stopping “the extraordinary rains caused by the enemy”.13

Here we seem to meet with a vague reference to the Deluge legend. The Babylonian Ishtar was angered at the gods for causing the flood and destroying mankind, as is gathered from the Gilgamesh epic:

Then the Lady of the gods drew nigh,

And she lifted up the great jewels14 which Anu had made according to her wish (and said):

“What gods these are! By the jewels of lapis lazuli which are upon my neck, I will not forget!

These days I have set in my memory, never will I forget them!

Let the gods come to the offering,

But Bel shall not come to the offering,

Since he refused to ask counsel and sent the deluge,

And handed over my people unto destruction.”15

A goddess who protests against the destruction of her human descendants by means of a flood, caused by the gods, was likely to protect them against “extraordinary rains”, caused by their human or demoniac enemies.

As we have seen in previous chapters, the Chinese Deluge legend, in one of its forms, was attached to the memory of the mythical Empress Nu Kwa, the sister of the mythical Emperor Fuh-hi, sometimes referred to as “the Chinese Adam”. Three rebels had conspired with the demons or gods of water and fire to destroy the world, and a great flood came on. Nu Kwa caused the waters to retreat by making use of charred reeds (quite a Babylonian touch!). Then she re-erected one of the four pillars of the sky against which one of the rebels, a huge giant, had bumped his head, causing it to topple over.

According to Chinese chronology, this world-flood occurred early in the “Patriarchal Period” between 2943 B.C. and 2868 B.C.

Another reference to the mother-goddess crops up in a poem by “the statesman poet, Chu Yuan, 332–295 B.C., who drowned himself”, Professor Giles writes,16 “in despair at his country’s outlook, and whose body is still searched for annually at the Dragon-boat Festival”. The poem in question is entitled “God Questions”, and one question is:

“As Nu-Chi had no husband, how could she bear nine sons?”

Professor Giles adds: “The Commentary tells us that Nu Chi was a ‘divine maiden’, but nothing more seems to be known about her”. It is evident that she was a virgin goddess, who, like the Egyptian Nut, was the spirit of the cosmic waters.17 It is of interest to find the memory of the poet associated with the Dragon-boat Festival, which, according to Chinese belief, had origin because he drowned himself in the Ni-ro River. There is evidence, however, that the festival had quite another origin. Dragon-boats were used in China on the fifth day of the fifth month at water festivals. They were “big ships adorned with carved dragon ornaments”, the yih bird being painted on the prow.18 De Visser says that these boats were used by emperors for pleasure trips, and music was played on board them. “The bird was painted, not to denote their swift sailing, but to suppress the water-gods.”19 According to De Groot, dragon-boat races were “intended to represent fighting dragons in order to cause a real dragon fight, which is always accompanied by heavy rains. The dragon-boats carried through the streets may also serve to cause rain, although they are at the same time considered to be substitutes.”20

Having drowned himself, the poet became associated with the river dragon. “Offerings of rice in bamboo”, says Giles, “were cast into the river as a sacrifice to the spirit of their great hero.”21 In like manner, offerings were made to dragons in connection with rain-getting ceremonies long before the poet was born. It is evident that he took the place of the dragon-god as the mythical Empress Nu Kwa of the Patriarchial Period took the place of the Chinese Ishtar, and as Ishtar took the place of the earlier Sumerian goddess Ninkharasagga, who, with “Anu, Enlil, and Enki”, “created the black-headed (i.e. mankind)”.22

The same Chinese poet sings of the mother-goddess in his poem, “The Genius of the Mountain”, which Professor Giles has translated:

“Methinks there is a Genius of the Hills clad in wistaria, girdled with ivy, with smiling lips, of witching mien, riding on the red pard, wild cats galloping in the rear, reclining in a chariot, with banners of cassia, cloaked with the orchid, girt with azalea, culling the perfume of sweet flowers to leave behind a memory in the heart.”

Like Ishtar, who laments for her lost Tammuz, this goddess laments for her “Prince”.

“Dark is the grove wherein I dwell. No light of day reached it ever. The path thither is dangerous and difficult to climb. Alone I stand on hill-top,23 while the clouds float beneath my feet, and all around is wrapped in gloom.”

This goddess is not only associated with ivy, the cassia tree, &c., but with the pine. “I shade myself”, she sings, “beneath the spreading pine.” The poem concludes:

“Now booms the thunder through the drizzling rain. The gibbons howl around me all the long night. The gale rushes fitfully through the whispering trees. And I am thinking of my Prince, but in vain; for I cannot lay my grief.”24

The goddess laments for her prince, as does Ishtar for Tammuz.

The mother-goddess is found also in the “Book of Odes” (The Shih King). She figures as the mother of the Hau-Ki and “the people of Kau” in the ode which begins as follows:

“The first birth of (our) people was from Kian Yuan. How did she give birth to our people? She had presented a pure offering and sacrificed, that her childlessness might be taken away. She then trod on a toe-print made by God, and was moved in the large place where she rested. She became pregnant; she dwelt retired; she gave birth to and nourished (a son), who was Hau-Ki.”25

Professor Giles refers to this birth-story “as an instance in Chinese literature, which, in the absence of any known husband, comes near suggesting the much-vexed question of parthenogenesis”.26

Other Chinese references to miraculous conceptions, given below, emphasize how persistent in Chinese legend are the lingering memories of the ancient mother-goddess.

As was the case in Babylonia and Egypt, the rival biological theories of the god cult and the goddess cult were fused or existed side by side in ancient China.

The goddess cult influenced Buddhism even when it was adopted in China, and fused with local religious systems. To the lower classes the “Poosa”, who brings luck—that is, success and protection—may be either a Buddha or a goddess. The name is “a shortened form of the Sanskrit term Bodhisattwa”, and was originally “a designation of a class of Buddha’s disciples.… The ‘Poosa’ feels more sympathy with the lower wants of men than the Buddha (Fuh) does.”

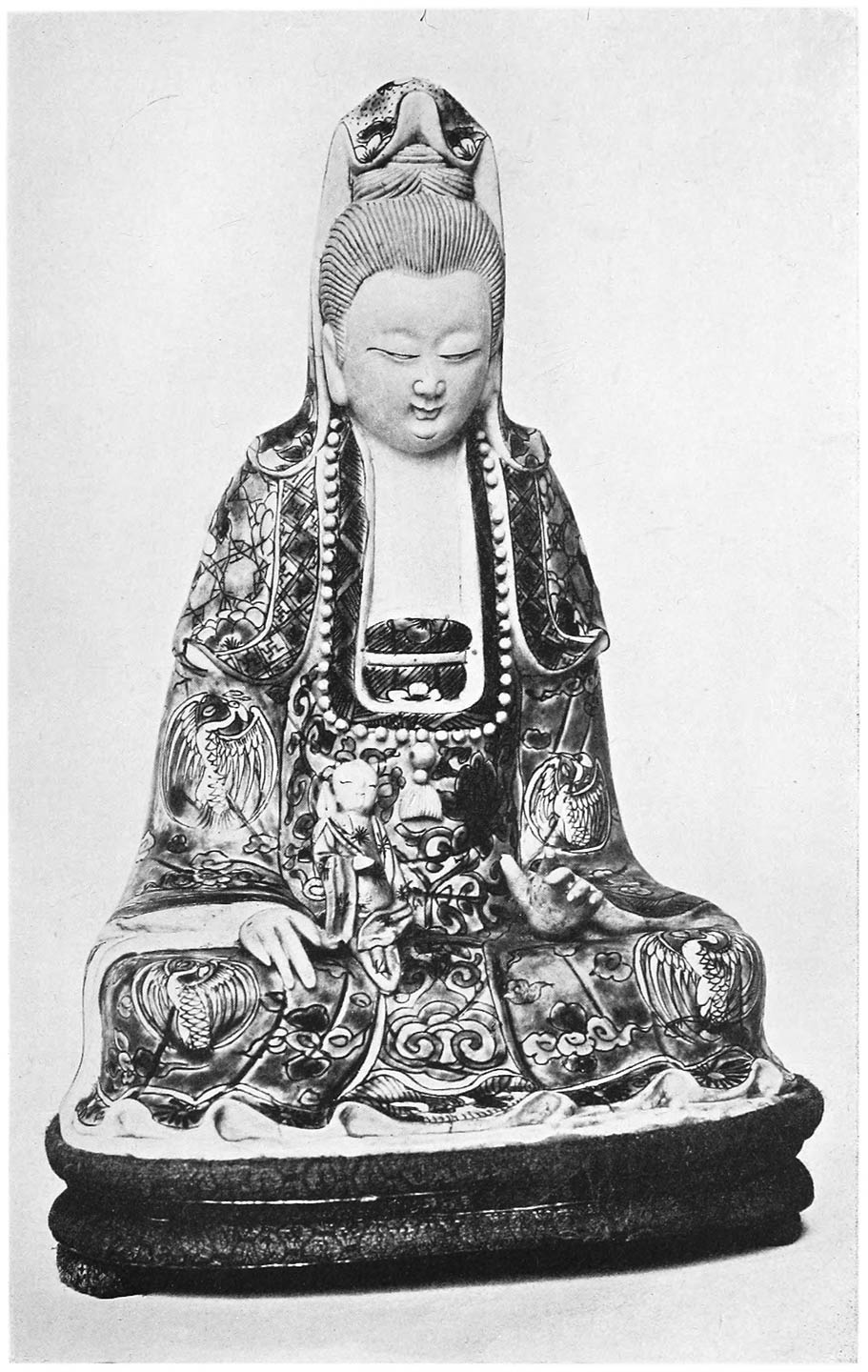

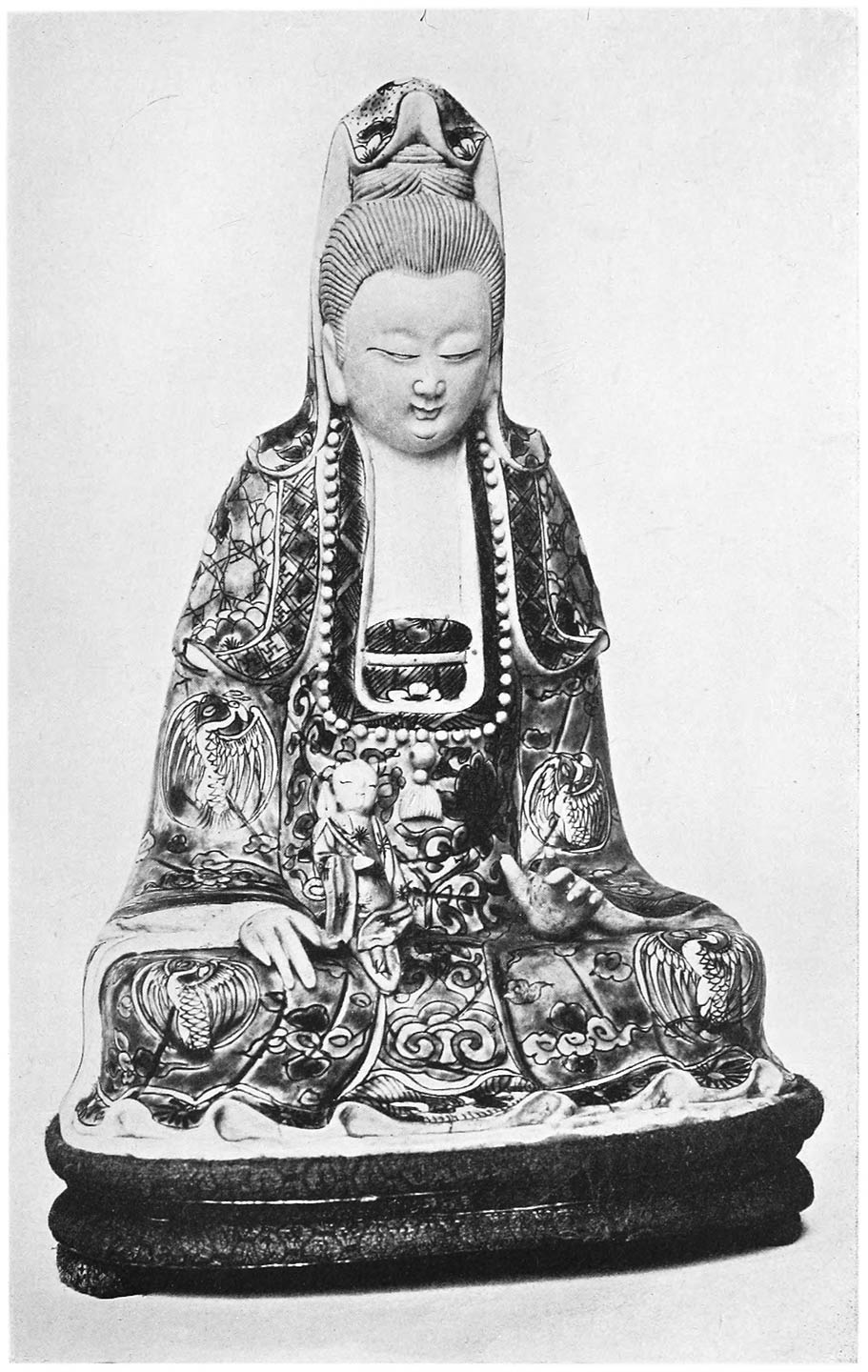

One of the holy beings referred to in China as a “Poosa” is Kwan-yin, the so-called “goddess of mercy”. Dr. Joseph Edkins27 says that “this divinity is represented sometimes as male, at others as female.… She is often represented with a child in her arms, and is then designated the giver of children. Elsewhere she is styled the ‘Kwan-yin who saves from the eight forms of suffering’ or ‘of the southern sea’, or ‘of the thousand arms’, &c. She passes through various metamorphoses, which give rise to a variety in names.”

KWAN-YIN, THE CHINESE “GODDESS OF MERCY”

From a porcelain figure decorated in soft enamels in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The “Poosa” of Buddhism or the ancient Chinese faith is a powerful protector. Dr. Edkins tells that “Chinese worshippers will sometimes say, for example, that they must spend a little money occasionally to obtain a favour of Poosa, in order to prevent calamities from assailing them. I saw”, he relates, “an instance of this at a town on the sea-coast near Hangchow. The tide here is extremely destructive in the autumn.28 It often overflows the embankment made to restrain it, and produces devastation in the adjoining cottages and fields. A temple was erected to the Poosa Kwan-yin, and offerings are regularly made to her, and prayers presented for protection against the tide.”

A vision of this Chinese Aphrodite was beheld about two years before the British forces captured Canton. “The governor of the province to which that city belongs”, says Dr. Edkins, “was engaged in exterminating large bands of roving plunderers that disturbed the region under his jurisdiction. He wrote to the Emperor on one occasion a dispatch in which he said that, at a critical juncture in a recent contest, a large figure in white had been seen beckoning to the army from the sky. It was Kwan-yin. The soldiers were inspired with courage, and won an easy victory over the enemy.”

Edkins notes that “the principal seat of the worship of Kwan-yin is at the island of Poots”. Here the deity “takes the place of Buddha, and occupies the chief position in the temples”. There are many small caves on the island dedicated to the use of hermits. “In several of them, high up on a hill-side”, Dr. Edkins “noticed a small figure of Buddha”. Here we have an excellent instance of “culture-mixing” in China in our own day.

Shang-ti, the personal god who rules in the sky, is to the Chinese Buddhists identical with Indra, the Hindu god of thunder and rain. In India Indra was in Vedic times the king of the gods, but in the Brahmanic Age became a lesser being than Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu. When Buddha was elevated to the godhead these great deities shrank into minor positions. In China they stand among the auditors of the supreme Buddha, as he sits on the lotus flower, and “occupy”, as Edkins found, “a lower position than the personages called Poosa, Lohan, &c.”29

In the next chapter it will be found that floating myths were attached to the memories of mythical and legendary monarchs in China, and that not a few of these myths resemble others found elsewhere.