CHAPTER XIII

THE SYMBOLISM OF JADE

Jade in Early Times—Used to Reanimate and Preserve the Dead—Jade as a Night-shining Jewel—Connection with the Pearl, Coral, Mandrake, Moon, Dragon, Fish, &c.—Jade Beliefs in Japan—Jade Amulets—The Chinese Cicada Amulet and Egyptian Search—Butterfly, Frog, and Bird Amulets—Jade and the Mother-goddess—The Chinese Universe—Great Bear and “World Mill”—Babylonian Astronomy in China—Star Deities—The Fung-shui Doctrine—Jade Symbols of Deities—Tigress as a Mother-goddess—Links with the West—The Two Souls in China and Egypt—Jade as an Elixir—Jade and Herbs—Jade and Babylonian Nig-gil-ma—Jade and Rhinoceros Horn—Jade Beliefs in Prehistoric Europe—Jade and Colour Symbolism—Jade contains Heat and Moisture—Jade as “The Jewel that Grants all Desires”.

One’s thoughts at once turn to China when mention is made of jade, for in no other country in the world has it been utilized for such a variety of purposes or connected more closely with the social organization and with religious beliefs and ceremonies.

This tough mineral, which is also called nephrite and “axe-stone”, and is of different chemical composition to jadeite, was known to the Chinese at the very dawn of their history. It was used by them at first like flint or obsidian for the manufacture of axes, arrow-heads, knives, and chisels, as well as for votive objects and personal ornaments of magical or religious character, and then, as time went on, for mortuary amulets, for images or symbols of deities, for mirrors,1 for seals and symbols of rank, and even for musical instruments, possessing, as it does, wonderful resonant qualities. The latter include jade flutes and jade “luck gongs”, which have religious associations.

Native artisans acquired great skill in working this tenacious mineral, and the finest art products in China are those exquisite jade ornaments, symbols, and vessels that survive from various periods of its history. Not only did the accomplished and patient workers, especially of the Han period (200 B.C.–200 A.D.), achieve a high degree of excellence in carving and engraving jade, and in producing beautiful forms; they also dealt with their hard mineral so as to utilize its various colours and shades, and thus increase the æsthetic qualities of their art products. The artistic genius, as well as the religious beliefs, of the Chinese has been enshrined in nephrite.

When the prehistoric Chinese settled in Shensi, they found jade in that area. “All the Chinese questioned by me, experts in antiquarian matters, agree”, Laufer writes, “in stating that the jades of the Chou and Han Dynasties are made of indigenous material once dug on the very soil of Shensi Province, that these quarries have been long ago exhausted, no jade whatever being found there nowadays. My informant pointed to Lan-tʼien and Fêng-siang-fu as the chief ancient mines.”2

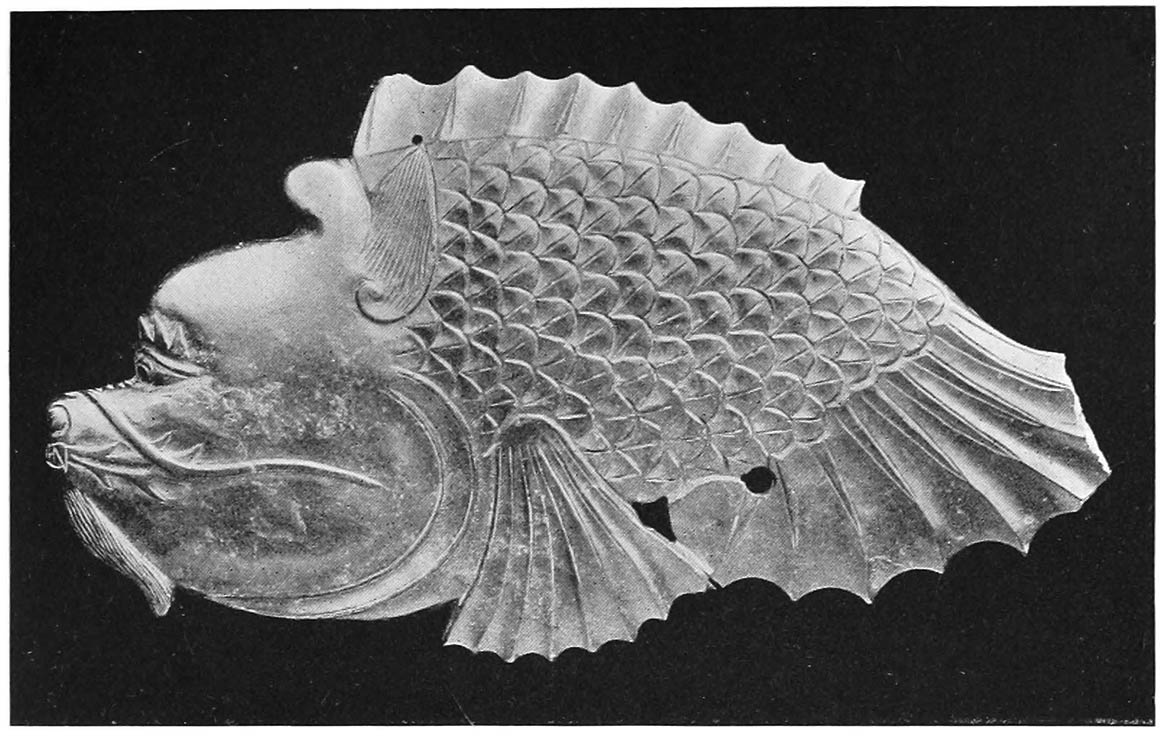

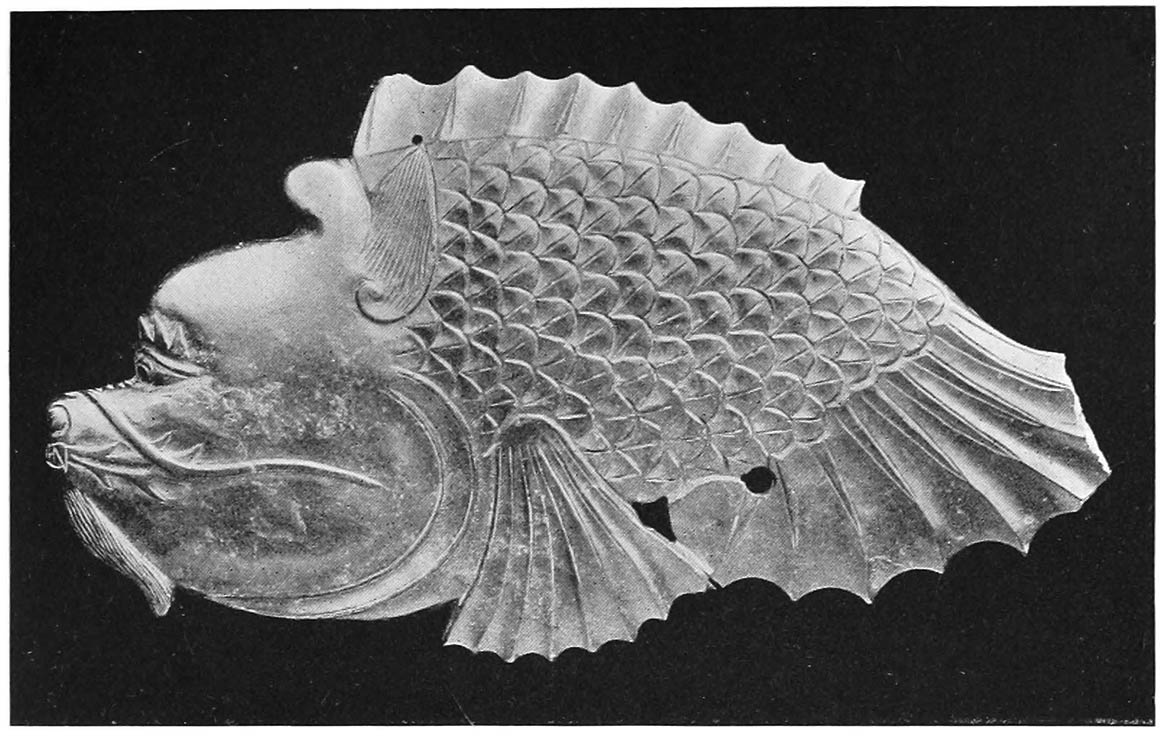

MORTUARY FISH IN JADE, OF HAN PERIOD

Laufer refers to this as “a marvellous carving of exceedingly fine workmanship”. In the Han Period sacrifices were offered to a fish in jade in prayers for rain.

FIGURE OF BUTTERFLY IN WHITE AND BROWNISH-YELLOW JADE, TSʼIN OR HAN PERIOD

A unique specimen among mortuary offerings of considerable age and unusual workmanship. A plum-blossom pattern is depicted between the antennæ of the butterfly (see page 225).

Both pictures by courtesy of B. Laufer, author of “Jade”, Field Museum, Chicago

But although the early Chinese made use of indigenous jade, it does not follow, as has been noted, that the early beliefs connected with this famous mineral were of indigenous origin. It cannot be overlooked that the symbolism of jade is similar in character to the older symbolism of pearls, precious stones, and precious metals, and that the associated beliefs can be traced not in China alone, but in such widely-separated countries as India, Babylonia, and Egypt. There was evidently a psychological motive for the importance attached by the early Chinese to jade, which they called yu.3 It had been regarded elsewhere as a precious mineral before they began to search for it and make use of it, especially for religious purposes.

It is not necessary to go back to the “Age of Stone” to theorize regarding Chinese jade beliefs. It has yet to be established that China had a Neolithic Age. “As far as the present state of our archæological knowledge and the literary records point out”, says Laufer, “the Chinese have never passed through an epoch which, for other culture regions, has been designated as a Stone Age.”4

Stone implements have been found, but, as in ancient Egypt, these were still being manufactured long after metals came into general use.

The fact that the same beliefs were connected with jade as with pearls, shells, gold, &c., is brought out very clearly in Chinese records regarding ancient burial customs. It was considered to be as necessary in ancient China as in ancient Egypt that the bodies of the dead should be preserved from decay. The Egyptians mummified their dead, and laid on and beside them a variety of charms that were supposed to afford protection and assist in the process of reanimation; withal, food offerings were provided. The Chinese, who have long been noted for their tendency to find substitutes for religious offerings, including paper money, believed that the bodies of the dead could be preserved by magic. At any rate, they did not consider it necessary to practise the science of mummification. In the Li Ki (chapter 56) the orthodox treatment of the bodies of the Emperor and others is set forth as follows:

“The mouth of the Son of Heaven is stuffed with nine cowries, that of a feudal lord with seven, that of a great officer with five, and that of an ordinary official with three”.5

Gold and jade were used in like manner. Laufer quotes from Ko Hung the significant statement: “If there is gold and jade in the nine apertures of the corpse, it will preserve the body from putrefaction”. A fifth-century Chinese writer says: “When on opening an ancient grave the corpse looks like alive, then there is inside and outside of the body a large quantity of gold and jade. According to the regulations of the Han Dynasty, princes and lords were buried in clothes adorned with pearls and with boxes of jade for the purpose of preserving the body from decay.”6

According to De Groot, pearls were introduced into the mouth of the dead during the Han Dynasty. “At least”, he says, “it is stated that their mouths were filled with rice, and pearls and jade stone were put therein, in accordance with the established ceremonial usages.” And Poh hu thung i, a well-known work, professedly written in the first century, says: “On stuffing the mouth of the Son of Heaven with rice, they put jade therein; in the case of a feudal lord they introduce pearls; in that of a great officer and so downwards, as also in that of ordinary officials, cowries are used to this end”.

De Groot, commenting on the evidence, writes: “The same reasons why gold and jade were used for stuffing the mouth of the dead hold good for the use of pearls in this connection”. He notes that in Chinese literature pearls were regarded as “depositories of Yang matter”, that medical works declare “they can further and facilitate the procreation of children”, and “can be useful for recalling to life those who have expired, or are at the point of dying”.7

In India, as a Bengali friend, Mr. Jimut Bahan Sen, M.A., informs me, a native medicine administered to those who are believed to be at the point of death is a mixture of pounded gold and mercury. It is named Makara-dhwaja. The makara8 is in India depicted in a variety of forms. As a composite lion-legged and fish-tailed “wonder beast” resembling the Chinese dragon, it is the vehicle of the god Varuna, as the Babylonian “sea goat” or “antelope fish” is the vehicle of the god Ea or of the god Marduk (Merodach). The makara of the northern Buddhists is likewise a combination of land and sea animals or reptiles, including the dolphin with the head of an elephant, goat, ram, lion, dog, or alligator.9

In China the lion-headed shark, a form of the sea-god, is likewise a makara or sea-dragon. Gold and night-shining pearls are connected with the makara as with the dragon. The Chinese dragon, as we have seen, is born from gold, while curative herbs like the “Red Cloud herb” and the “dragon’s whiskers herb” are emanations of the dragon. Gold, like the herb, contains “soul substance” in concentrated form. Pounded gold, the chief ingredient in the makara-dhwaja medicine, is believed in India to renew youth and promote longevity like pounded jade and gold in China.

“In Yung-cheu, which is situated in the Eastern Ocean, rocks exist,” wrote a Chinese sage in the early part of the Christian era. “From these rocks there issues a brook like sweet wine; it is called the Brook of Jade Must. If, after drinking some pints out of it, one suddenly feels intoxicated, it will prolong life.… Grease of jade,” we are further told, “is formed inside the mountains which contain jade. It is always to be found in steep and dangerous spots.10 The jade juice, after issuing from those mountains, coagulates into such grease after more than ten thousand years. This grease is fresh and limpid, like crystal. If you find it, pulverize it and mix it with the juice of herbs that have no pith; it immediately liquefies; drink one pint of it then and you will live a thousand years.… He who swallows gold will exist as long as gold; he who swallows jade will exist as long as jade. Those who swallow the real essence of the dark sphere (heavens) will enjoy an everlasting existence; the real essence of the dark sphere is another name for jade. Bits of jade, when swallowed or taken with water, can in both these cases render man immortal.”11

As we have seen, the belief prevailed in China that pearls shone by night. The mandrake root was believed elsewhere to shine in like manner. The view is consequently urged by the writer that the myths regarding precious stones, jade, pearls, and herbs of nocturnal luminosity owe their origin to the arbitrary connection of these objects with the moon, and the lunar-goddess or sky-goddess. In China Ye Kuang (“light of the night”) “is”, Laufer notes, “an ancient term to designate the moon”.12

The intimate connection between the Mother deity and precious metals and stones is brought out by Lucian in his De Dea Syria. He refers to the goddess Hera of Hierapolis, who has “something of the attributes of Athene, and of Aphrodite, and of Selene, and of Rhea, and of Artemis, and of Nemesis, and of the Fates”, and describes her as follows:

“In one of her hands she holds a sceptre, and in the other a distaff;13 on her head she bears rays and a tower, and she has a girdle wherewith they adorn none but Aphrodite of the sky. And without she is gilt with gold, and gems of great price adorn her, some white, some sea-green, others wine-dark, others flashing like fire. Besides these there are many onyxes from Sardinia, and the jacinth and emeralds, the offerings of the Egyptians and of the Indians, Ethiopians, Medes, Armenians, and Babylonians. But the greatest wonder of all I will proceed to tell: she bears a gem on her head, called a Lychnis; it takes its name from its attribute. From this stone flashes a great light in the night-time, so that the whole temple gleams brightly as by the light of myriads of candles, but in the day-time the brightness grows faint; the gem has the likeness of a bright fire.”14

Laufer notes in his The Diamond15 that “the name lychnis is connected with the Greek lychnos” (“a portable lamp”), and that, “according to Pliny, the stone is so called from its lustre being heightened by the light of a lamp”. He thinks the stone in question is the tourmaline. Laufer reviews a mass of evidence regarding precious stones that were reported to shine by night, and comes to the conclusion that there is no evidence on record “to show that the Chinese ever understood how to render precious stones phosphorescent”. He adds: “Since this experiment is difficult, there is hardly reason to believe that they should ever have attempted it. Altogether,” he concludes, “we have to regard the traditions about gems luminous at night, not as a result of scientific effort, but as folk-lore connecting the Orient with the Occident, Chinese society with the Hellenistic world.” As Laufer shows, the Chinese imported legends regarding magical gems from Fu-lin (“the forest of Fu”), an island in the Mediterranean Sea, which was known to them as “the Western Sea” (Si hai).16 At a very much earlier period they imported other legends and beliefs regarding metals and minerals.

Pearls and gold having been connected with the makara or dragon, it is not surprising to find that their lunar attributes were imparted to jade. Laufer quotes Chinese references to the “moonlight pearl” and the “moon-reflecting gem”,17 while De Groot deals with Chinese legends about “effulgent pearls”, about “pearls shining during the night”, “flaming or fiery pearls”, and “pearls lighting like the moon”. De Groot adds, “Similar legends have always been current in the empire (of China) about jade stone”, and he notes in this regard that “at the time of the Emperor Shen-nung (twenty-fifth century B.C.) there existed”, according to Chinese records, “jade which was obtained from agate rocks, under the name of ‘Light shining at night’. If cast into the waters in the dark it floated on the surface, without its light being extinguished.”18

The wishing jewel (“Jewel that grants all desires”) of India, Japan, and China is said to be “the pupil of a fish eye”. In India it was known in Sanskrit as the cintimani, and was believed to have originated from the makara.19 The Chinese records have references to “moonlight pearls” from the eyes of female whales, and from the eyes of dolphins.20 It does not follow that this belief about the origin of shining pearls had a connection with observations made of the phosphorescing of parts of marine animals, because the Chinese writers refer too, for instance, to the nocturnal luminosity of rhinoceros horn.21 Even coral, which, like jade, was connected with the lunar- or sky-goddess, was supposed to shine by night. Laufer quotes from the work, Si King tsa (Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital, i.e. Si-ngan-fu), in this connection:

“In the pond Tsi-tsʼui there are coral trees twelve feet high. Each trunk produces three stems, which send forth 426 branches. These have been presented by Chao Tʼo, King of Nan Yūe (Annam), and were styled ‘beacon-fire trees’. At night they emitted a brilliant light as though they would go up in flames.”22

The “coral tree” here links with the pine, peach, and cassia trees, and the shining mandrake, as well as with jade, gold, precious stones, and pearls. In Persia the pearl and coral are called margan, which signifies “life-giver” or “life-owner”. Lapis-lazuli was called Kin tsin (“essence of gold”) during the Tiang period in China.23

As the metal associated with the moon was usually silver, gold being chiefly, although not always, the sun metal, we should expect to find silver connected with jade and pearls.

De Groot, who is frankly puzzled over Chinese beliefs regarding pearls, and has to “plead incompetency” to solve the problem why they were “considered as depositories and distributors of vital force”,24 provides the translation of a passage in the Ta Tsʼing thung li that connects silver with pearls. It states in reference to burial customs that “in the case of an official of the first, second, or third degree, five small pearls and pieces of jade shall be used for stuffing the mouth; in that of one of the fourth, fifth, sixth, or seventh rank, five small pieces of gold and of jade. The gentry shall use three bits of broken gold or silver; among ordinary people the mouth shall be stuffed with three pieces of silver.”

De Groot insists that the principal object of the practice of stuffing the mouths of the dead was “to save the body from a speedy decay”.25

It is significant therefore to find references in Chinese literature to “Pearls of Jade”, to “Fire Jade” that sheds light or even “boils a pot”, and to find silver being regarded as a substitute for jade. Shells, pearls, gold, silver, and jade contained “soul substance” derived from the Great Mother. As we have seen, Nu Kwa, the mythical Chinese Empress (the sister of Fu Hi, the “Chinese Adam”), who stopped the Deluge, took the place of the ancient goddess in popular legend. She was credited, as has been indicated, with planning the course of the Celestial River, with creating dragons, with re-erecting one of the four pillars that supported the firmament, and with creating jade for the benefit of mankind. In Japan Nu Kwa is remembered as Jokwa.

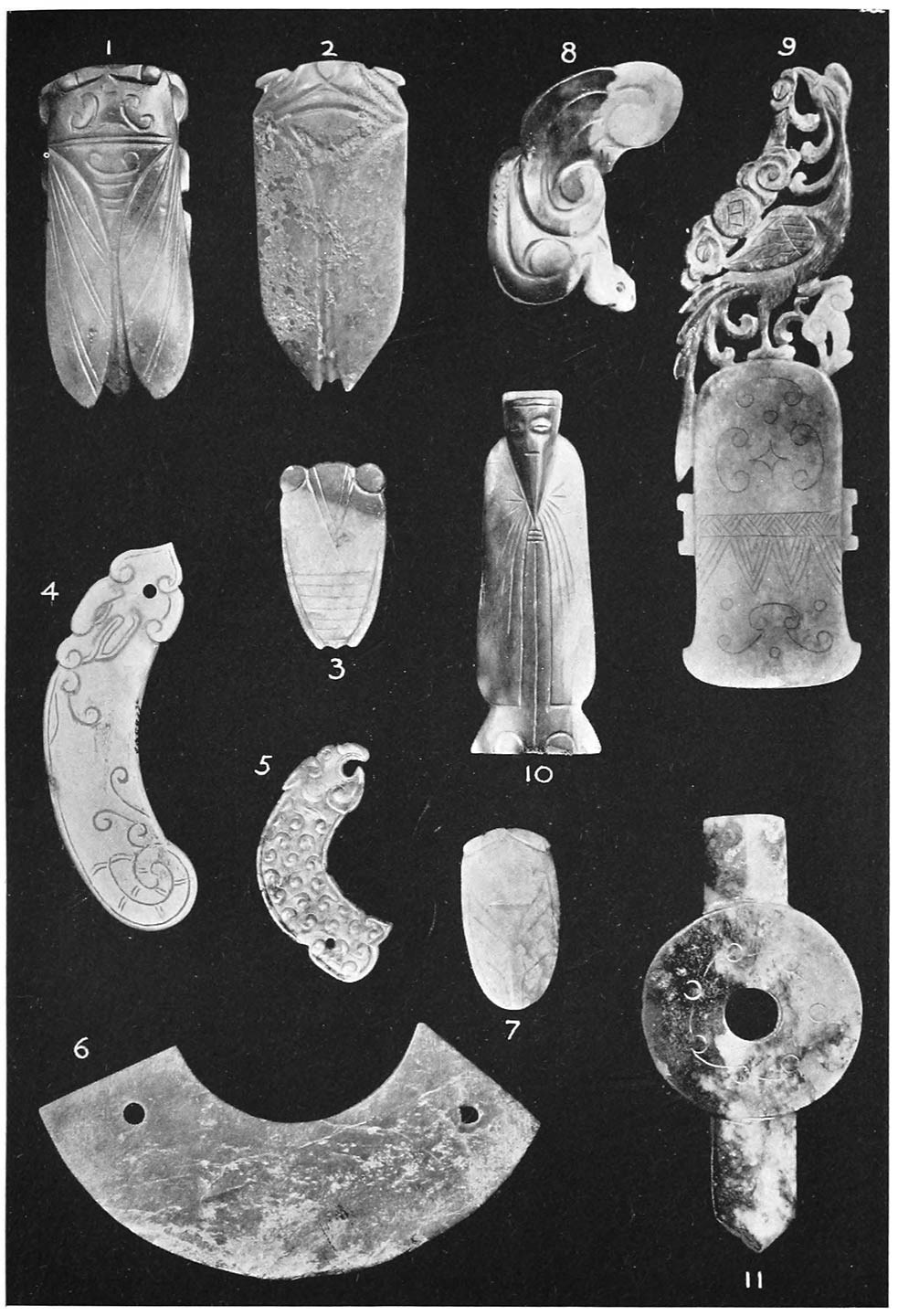

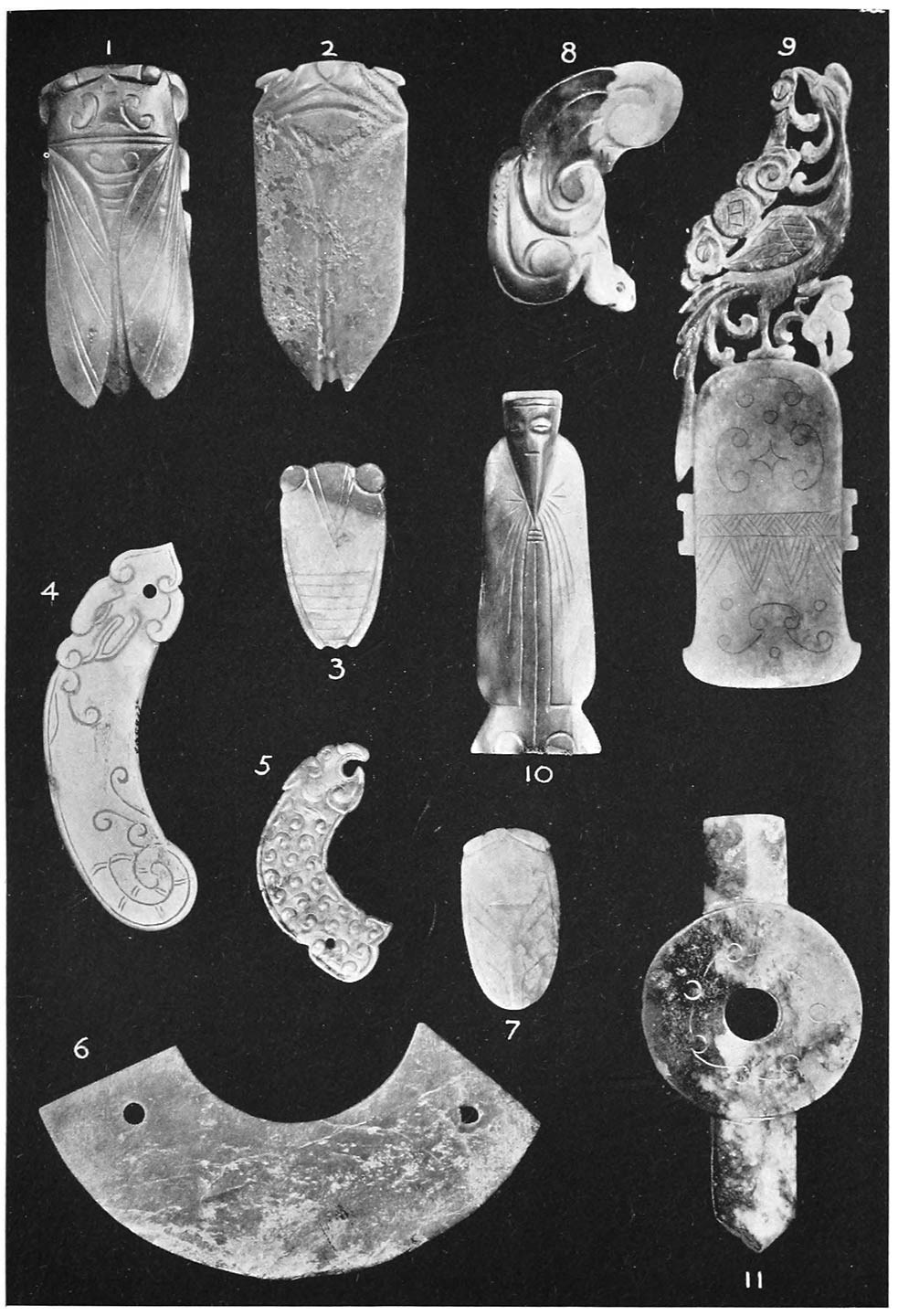

AMULETS FOR THE DEAD, AND OTHER OBJECTS IN JADE

1. 2. 3. 7. Tongue Amulets. 4. Amulet for eye. 5. 6. Lip amulets. 8. Girdle in shape of fungus of immortality. 9. Axe-shaped girdle ornament. 10. Carving of man (Han Period). 11. Jade image (Knei Pi) used in sacrifices to sun, moon and stars.

By courtesy of B. Laufer, author of “Jade”, Field Museum, Chicago

The Japanese beliefs connected with jade are clearly traceable to China. A Tama may be a piece of jade, a crystal, a tapering pearl, or the pearl carried on the head of a Japanese dragon. “The Tama”, says Joly, “is associated not only with the Bosatsu and other Buddhist deities or saints, but also with the gods of luck.”26 There are a number of heroic legends in which the Tama figures. In a story, relegated to the eighth century B.C., a famous jade stone is called “the Tama”. It tells that Pien Ho (the Japanese Benwa) saw an eagle standing on a large block of jade which he took possession of and carried to his king. The royal magicians thought it valueless, and Benwa’s right foot was cut off. He made his way to the mountains and replaced the jade, and soon afterwards observed that the same eagle returned and perched upon it again. When a new king came to the throne Benwa carried the jade to the court, but only to have his left foot cut off. A third king came to the throne, and on seeing Benwa weeping by the gate of the palace he inquired into the cause of his grief, and had the stone tested, when it was found to be a perfect gem. This Tama was afterwards regarded so valuable that it was demanded as “a ransom for fifteen cities”.27

Here the eagle is associated with the gems containing “soul substance”. Joly notes that “foxes are also shown holding the Tama”, and he wonders if the globe “held under their talons by the heraldic lions has a similar meaning”.28 Foxes and wolves were, like dragons, capable of assuming human form and figure among the were-animals of the Far East. As these were-animals include the tiger, which is a god in China, it is possible that they were ancient deities. The lion is associated with the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, with the Cretan mother-goddess, while the Egyptian Tefnut has a lioness form. Tammuz of Babylon is, as Nin-girsu of Lagash, a lion-headed eagle. The Indian Vishnu has a lion-headed avatar.

The connection of the precious jewel and of gold with the supreme deity is traceable to the ancient beliefs regarding the shark-guardian of pearls. As the beliefs associated with pearls were transferred to jade, it need not surprise us to find the sacred fish—a form of the Great Mother—connected with jade. A significant text is quoted by Laufer, without comment, which brings out this connection. He says that “Lü Pu-wei, who died in B.C. 235, reports in his book Lu-shih Chʼun Tsʼiu: ‘Pearls are placed in the mouth of the dead, and fish-scales are added; these are now utilized for interment with the dead.’ The Commentary to this passage explains: ‘To place pearls in the mouth of the dead (han chu) means to fill the mouth with them; the addition of fish-scales means, to enclose these in a jade casket which is placed on the body of the deceased, as if it should be covered with fish-scales.’ ”29 Jade fish-symbols figure among the Chinese mortuary amulets.

Light is thrown on Chinese beliefs regarding resurrection by the cicada mortuary amulet which was made of jade. It was placed on the tongue of the dead and seems therefore to have been like the Egyptian scarab amulet, a guarantee of immortality.

One of the important ceremonies in connection with the process of reanimating an Egyptian corpse was “the opening of the mouth”. It was necessary that the reanimated corpse should speak with “the true voice” and justify itself in the court of Osiris, judge of the dead, when the heart was weighed in the balance.

Tongue and heart were closely connected. According to the beliefs associated with the cult of Ptah, which was fused with the cult of Osiris, the heart was “the mind”, and the source of all power and all life. The tongue expressed the thoughts of the mind.

Ptah, the great, is the mind and tongue of the gods.

Ptah, from whom proceeded the power

Of the mind,

And of the tongue.…

It (the mind) is the one that bringeth forth every successful issue.

It is the tongue that repeats the thoughts of the mind.30

The mind was the essence of life: the tongue, which formed the word, was the active agent of the mind (heart).

As “the stuffing of the corpse with jade took the place of embalming”31 in China, the custom of placing a jade amulet on the tongue is of marked significance. It is quite evidently an imported custom. The cicada takes the place of the Egyptian scarabæus, the beetle-god of Egypt, named Khepera and called in the texts “father of the gods”. In ancient Egypt scarabs were placed on the bodies and in the tombs of the dead to protect heart (mind) and tongue and ensure resurrection. A text sets forth in this connection: “And behold, thou shalt make a scarab of green stone, with a rim of gold, and this shall be placed in the heart of a man, and it shall perform for him the ‘Opening of the Mouth’ ”. The scarab is to be anointed with “ānti unguent” and then “words of power” are to be recited over it. In “words of power” the deceased addresses the scarab as “my heart, my mother: my heart whereby I came into being”.

The beetle-god, in whose form the scarab was made, “becomes”, as Budge says, “in a manner a type of the dead body, that is to say, he represents matter containing a living germ which is about to pass from a state of inertness into one of active life. As he was a living germ in the abyss of Nu (the primeval deep) and made himself emerge therefrom in the form of the rising sun, so the germ of the living soul, which existed in the dead body of man, and was to burst into new life in a new world by means of the prayers recited during the performance of appropriate ceremonies, emerged from its old body in a new form either in the realm of Osiris or in the boat of Ra (the sun-god).”32

This Egyptian doctrine was symbolized by the beetle which rolls a bit of dung in the dust into the form of a ball, and then, having dug a hole in the ground, pushes it in and buries it. Thereafter the beetle enters the subterranean chamber to devour the ball. This beetle also collects dung to feed the larvæ which ultimately emerge from the ground in beetle form.

As the Chinese substituted jade for pearls, so did they substitute the cicada for the dung-beetle.

The cicada belongs to that class of insect which feeds on the juices of plants. It is large and broad with brightly-coloured wings. The male has on each side of the body a sort of drum which enables it to make that chirping noise called “the song of the cicada”, referred to by the ancient classical poets. When the female lays her eggs she bores a hole in a tree and deposits them in it. Wingless larvæ are hatched, and they bore their way into the ground to feed on the juices of roots. After a time—in some cases after the lapse of several years—the cicada emerges from the ground, the skin breaks open, and the winged insect rises in the air. The most remarkable species of the cicada is found in the United States, where it passes through a life-history of seventeen years, the greater part of that time being spent underground—the larval stage. In China the newly-hatched larva sometimes bores down into the earth to a depth of about twenty feet.

“The observation of this wonderful process of nature,” says Laufer, “seems to be the basic idea of this (cicada) amulet. The dead will awaken to a new life from his grave as the chirping cicada rises from the pupa buried in the ground. This amulet, accordingly, was an emblem of resurrection.” Laufer quotes in this connection from the Chinese philosopher Wang Chʼung, who wrote: “Prior to casting off the exuviæ, a cicada is a chrysalis. When it casts them off, it leaves the pupa state, and is transformed into a cicada. The vital spirit of a dead man leaving the body may be compared to the cicada emerging from the chrysalis.”33

The fact that the cicada feeds on the juices of plants apparently connected it with the idea of the Tree of Life, the source of “soul substance”.

Another insect symbol of resurrection was the butterfly, which was connected with the Plum Tree of Life. Laufer notes that some butterflies carved from jade, which were used as mortuary amulets, have a plum-blossom pattern between the antennæ and plum-blossoms “carved à jour in the wings”.34

He notes that “in modern times the combination of butterfly and plum-blossom is used to express a rebus with the meaning ‘Always great age’”. This amulet is of great antiquity.

The butterfly symbol of resurrection is found in Mexico. The Codex Remensis shows an anthropomorphic butterfly from whose mouth a human face emerges. Freyja, the Scandinavian goddess, is connected with the butterfly, and in Greece and Italy the same insect was associated with the idea of resurrection. Psyche (a name signifying “soul”) has butterfly wings. Apparently the butterfly, like the cicada, was supposed to derive its vitality from the mother-goddess’s Tree of Life.

Another important Chinese mortuary jade object was the frog or toad amulet. As we have seen, the frog was connected with the moon and the lunar goddess, and in China, as in ancient Egypt, was a symbol of resurrection.

Among the interesting jade amulets shown by Laufer are two that roughly resemble in shape the Egyptian scarabs. “The two pieces”, he writes, “show traces of gilding, and resemble helmets in their shape, and are moulded into the figures of a curious monster which it is difficult to name. It seems to me that it is possibly some fabulous giant bird, for on the sides, two wings, each marked by five pinions, are brought out, a long, curved neck rises from below, though the two triangular ears do not fit the conception of a bird.”35 The figure apparently represents a “composite wonder beast”. Fishes and composite quadrapeds were also depicted in jade and placed in graves. Human figures are rare.

Stone coffins were used in ancient times. The books of the later Han Dynasty (at the beginning of our era) tell about a pious governor, Wang Khiao, who receives a jade coffin from heaven. It was placed by unseen hands in his hall. His servants endeavoured to take it away, but found it could not be moved.

De Groot,36 who translates the story, continues: “Khiao said, ‘Can this mean that the Emperor of Heaven calls me towards him?’ He bathed himself, put on his official attire with its ornaments, and lay down in the coffin, the lid being immediately closed over him. When the night had passed, they buried him on the east side of the city, and the earth heaped itself over him in the shape a tumulus. All the cows in the district on that evening were wet with perspiration and got out of breath, and nobody knew whence this came. The people thereupon erected a temple for him.”

De Groot quotes from another work written in the fifth century, which relates that “at Lin-siang there is in the water a couch of stone, upon which stand two coffins of solid stone, green like copper mirrors. There is nobody who can give information regarding them.”37

Here we have jade used for the preservation of the dead, associated with the sky, with cows, water, and stone, and, in addition, a reference to green copper. Jade has taken the place of pearls, and pearls were, as has been shown, connected with the mother-goddess, the sky and cow deity who was the source of fertilizing and creative moisture and “soul substance”. The standing stones of the mother-goddess were supposed to perspire, and to split and give birth to dragons or gods. This idea appears to lie behind the story regarding the perspiring cows. An influence was at work on the night when the sage was buried in the jade coffin, and that influence came from the sky, and was concentrated in jade. It is necessary, therefore, at this point, to get at Chinese ideas regarding the connection between jade and the mysterious influence or influences in what we call “Nature”.

Behind all mythologies lie basic ideas regarding the universe. To understand a local or localized mythology, it is necessary that we should know something regarding the world in which lived those who invented or perpetuated the myths.

The Chinese world was flat, and over it was the dome of the firmament supported by four pillars. These pillars were situated at the four cardinal points, and were each guarded by a sentinel deity. The deities exercised an influence on the world and on all living beings in it, and their influence was particularly strong during their seasons.

Like the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians the Chinese believed that their world was surrounded by water. There are references in the texts to the “Four Seas”, and to what the Egyptians called the “Great Circle” (Okeanos).

The Babylonians believed the world was a mountain, and their temples were models of their world. Thus the temple of Enlil, as the world-god, was called E-Kur, which signifies “mountain house”. His consort Ninlil was also called Nin-Kharsag, “the lady of the mountain”.38 The Babylonian and Egyptian temples were not only places of worship, but seats of learning, and they had workshops in which the dyers, metal-workers, &c., plied their sacred trades.

Chinese palaces and universities were in ancient times models of the world. One of the odes says of King Wu:

“In the capital of Hao he built his hall with its circlet of water. From the west to the east, from the south to the north, there was not a thought but did him homage.”39

This hall was a royal college, “built”, says Legge, “in the middle of a circle of water”. Colleges might also have semicircular pools in front of them, “as may now be seen in front of the temples of Confucius in the metropolitan cities of the provinces”.40 Ceremonies were studied in these institutions. There were also grave-pools. In Singapore these grave-pools have had to be abolished because they were utilized for hatching purposes by mosquitoes.

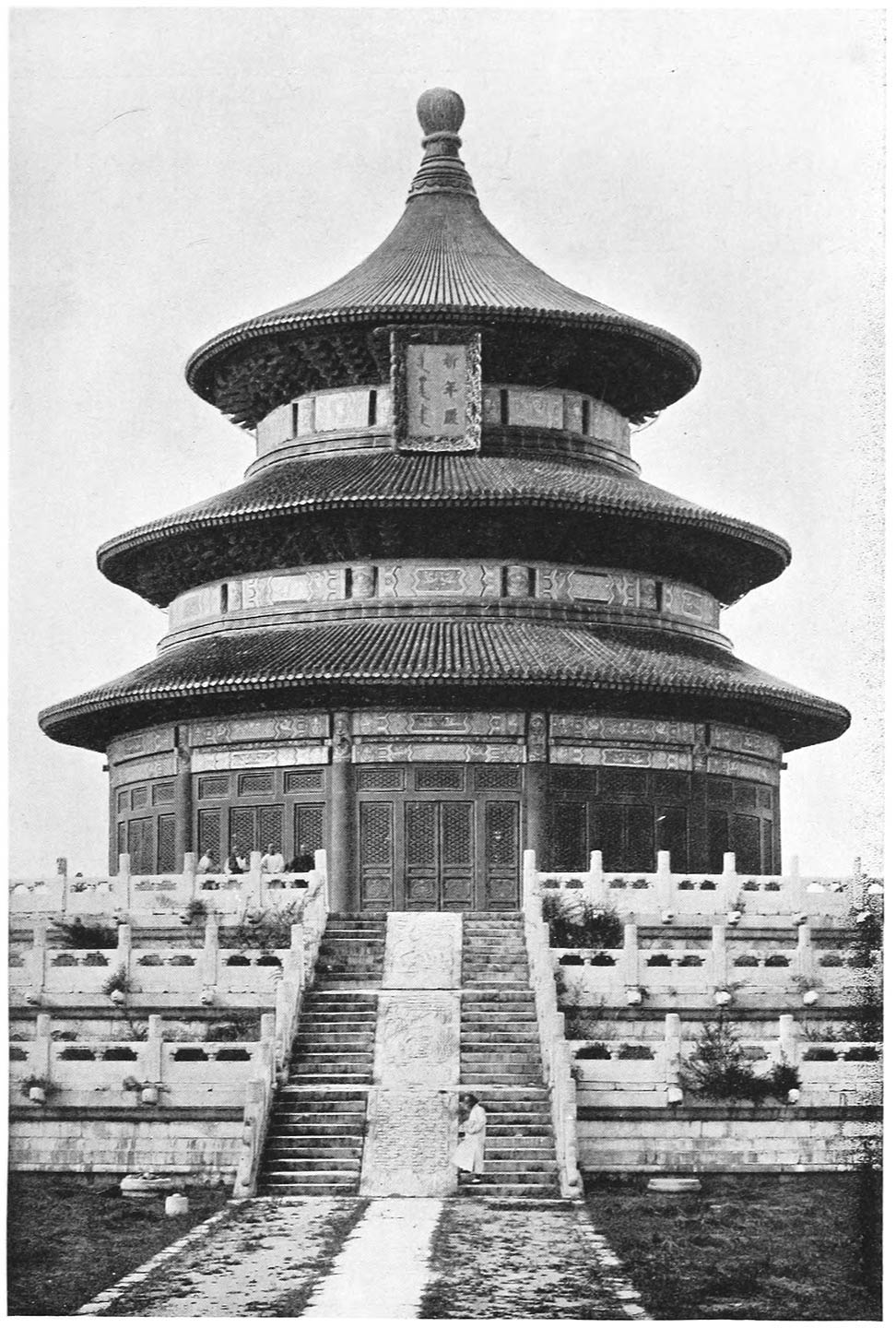

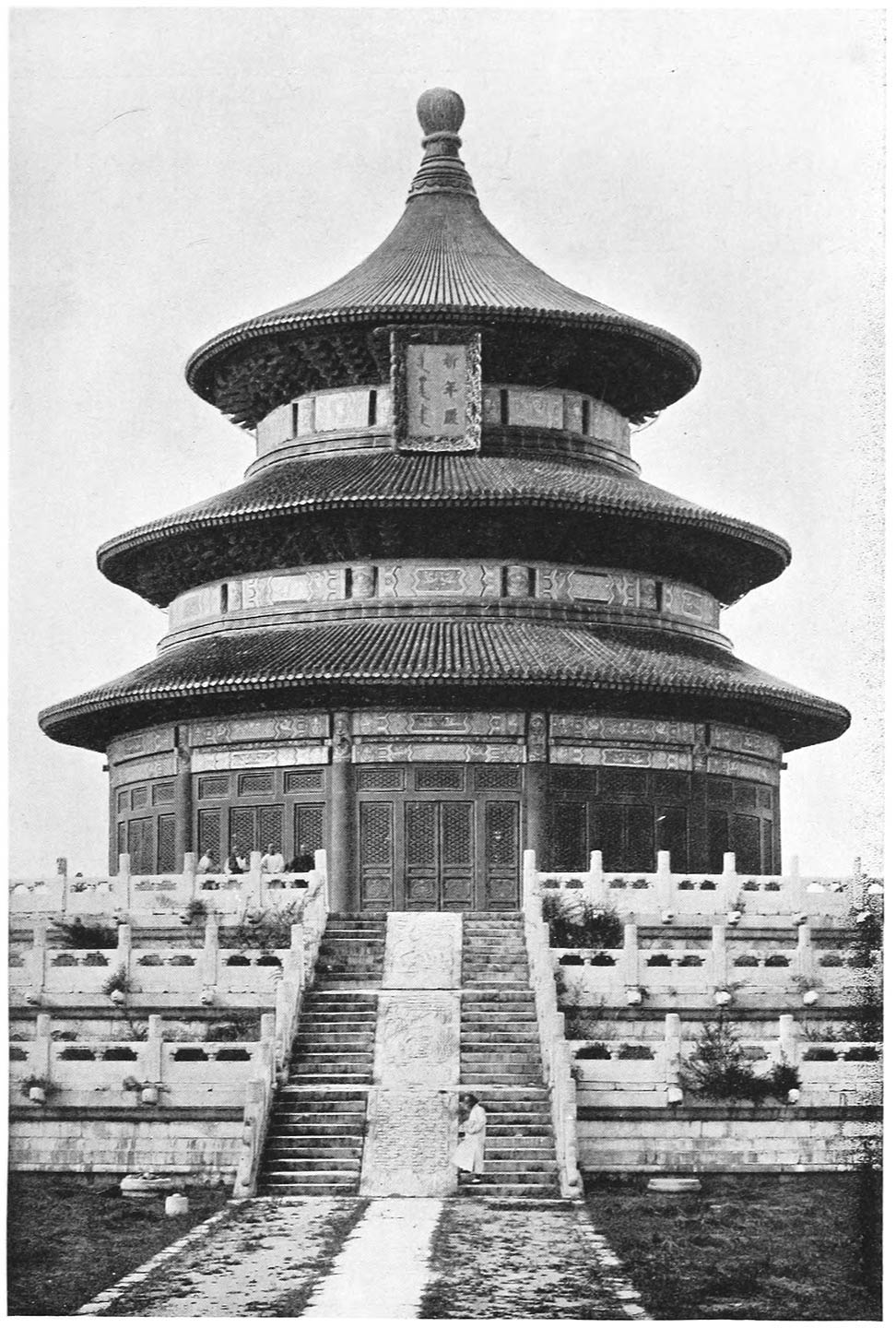

Copyright H. G. Ponting. F.R.G.S.

THE TEMPLE OF HEAVEN, PEKING

This greatest of Confucian temples, with its tiles of deep cobalt blue shining in the sunshine, is the most conspicuous object in the city. “During the ceremonies inside everything is blue; the sacrificial utensils are of blue porcelain, the worshippers are robed in blue, even the atmosphere is blue, venetians made of thin rods of blue glass, strung together by cords, being hung down over the tracery of the doors and windows” (Bushell).

Much attention was paid by the Chinese to the shape and situation of a temple, college, palace, or grave. Each was subjected to good and bad influences, and as seafarers set their sails to take full advantage of a favourable breeze, so did the Chinese construct edifices and graves to take full advantage of favourable influences emanating from what may be called the “magic tanks” of the universe—the cardinal points and the sky.

The beliefs involved in this custom are not peculiar to China. In Scottish Gaelic, for instance, there is the old saying:

Shut the north window,

And quickly close the window to the south;

And shut the window facing west;

Evil never came from the east.

Another saying is: “Shut the windows to the north, open the windows to the south, and do not let the fire go out”. Both in Scottish and Irish Gaelic the north is the “airt” (cardinal point) of evil influence, and is coloured black, as is the north in China, and the south in India. The black Indian south is “Yama’s gate”, that is the “gate” of the god of death. One cannot say anything worse to a Hindu than “Go to Yama’s gate”. The north is the good and white “airt” of Indian mythology; the good go northward to Paradise, as in Scotland they go southward. A Japanese poet has written: “The Paradise is in the south; only fools pray towards the west”.41

In the Pyramid Texts of ancient Egypt the east is held by the solar cult “to be the most sacred of all regions”, while the west is the sacred “airt” of the Osirian cult.42 In the east the sun-god, to whom the soul of the dead Pharaoh went, was supposed to be reborn every morning. The Chinese regarded the east “as the quarter”, says De Groot, “in which is rooted the life of everything, the great genitor of life (the sun) being born there every day”.43 As we have seen, there was in China, as in Egypt, a rival cult of the west.

The gods of the four quarters of China, from whom influences flowed, were: The Blue (or Green) Dragon (east), the Red Bird (south), the White Tiger (west), and the Black Tortoise (north). The east is the left side, and the west is the right side; a worshipper therefore faces the south. In Irish and Scottish Gaelic lore the south is the right side, and the north is the left side; a worshipper therefore faces the east.

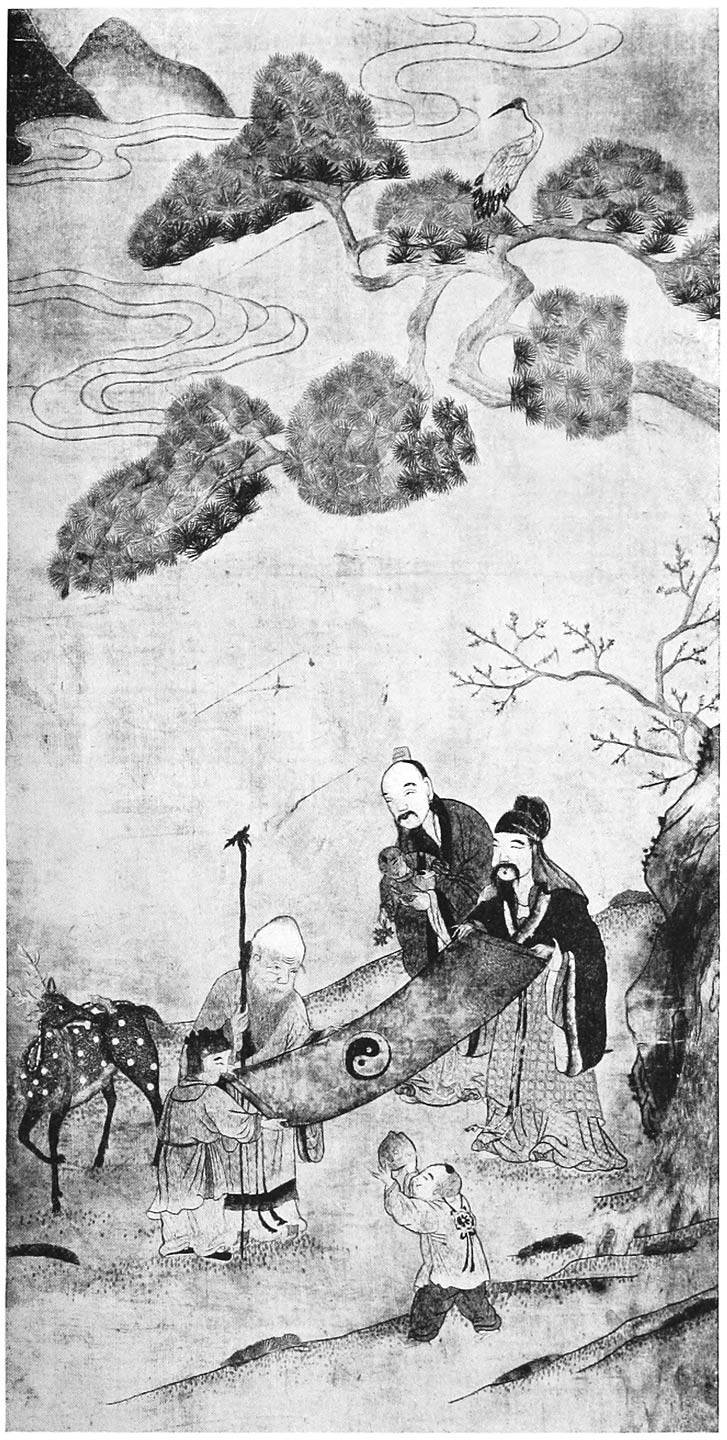

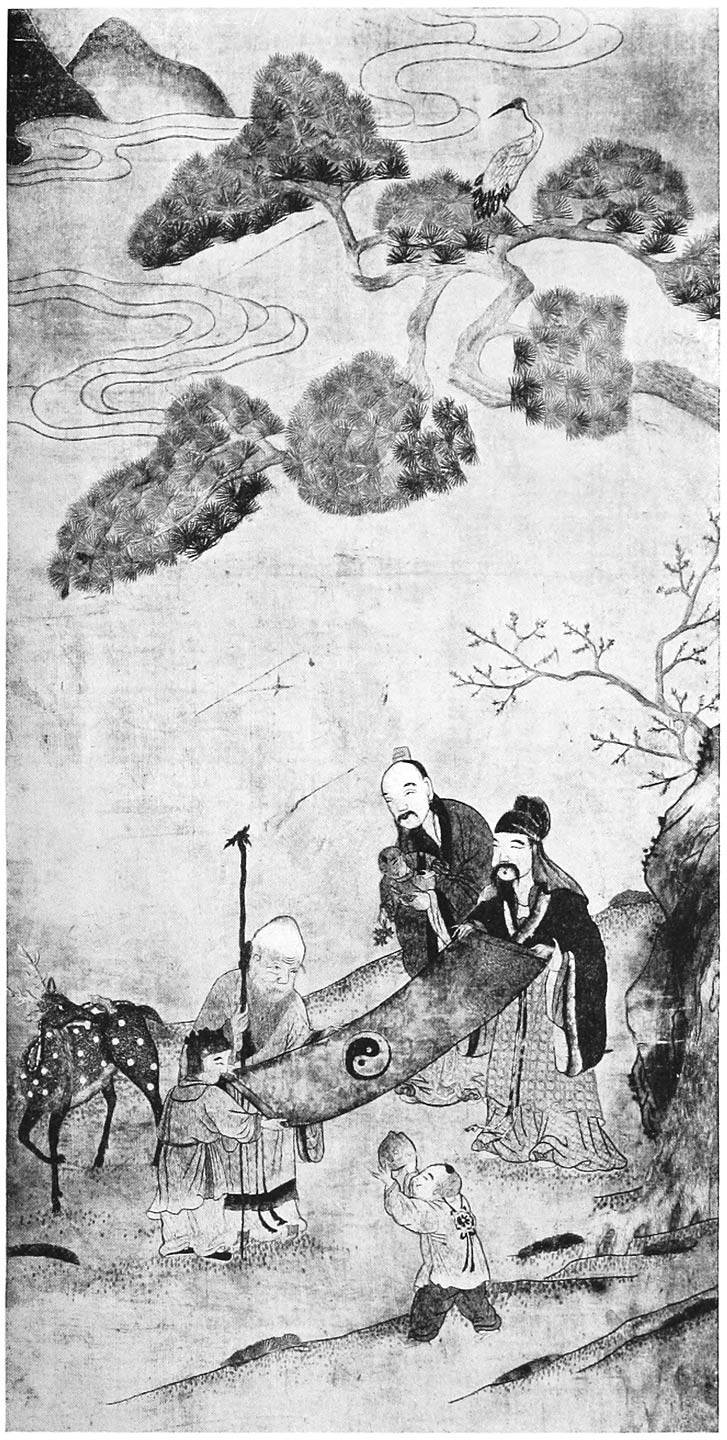

THREE SAGES STUDYING SYMBOL OF YIN AND YANG

(The Yin is the black and the Yang the white “comma” forming circle)

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

According to Kwang-tze, the Taoist, it was believed in China that “the breath (or influence) of the east is wind, and wind creates wood”; that “the breath of the south is Yang, which creates fire”; that “the centre is earth”; that “the breath of the west is Yin, which gives birth to metal”; and that the breath of the north “is cold, by which water is produced”. Another native pre-Christian writer says that “the east appertains to wood, the south to fire, the west to metal, and the north to water”.44 Thus taking in the seasons we have the following combinations, showing the organs of the body influenced by the gods of the “airts”:

East—the Blue Dragon, Spring, Wood; Planet, Jupiter; liver and gall.

South—the Red Bird, Summer, Fire, the Sun; Planet, Mars; heart and large intestines.

West—the White Tiger, Autumn, Wind, Metal; Planet, Venus; lungs and small intestine.

North—the Black Tortoise, Winter, Cold, Water; Planet, Mercury; kidneys and bladder.

The good influence (or breath) was summed up in the term Yang, and bad influence in the term Yin. Yang refers to what is bright, warm, active, and life-giving; and Yin to what is inactive, cold, and of the earth earthy. “When”, says a Chinese writer, “we speak of the Yin [2 and the Yang, we mean the air (or ether) collected in the Great Void. When we speak of the Hard and Soft, we mean that ether collected and formed into substance.”45 Says De Groot in this connection: “In China vital power is specially assimilated with the Yang, the chief part of the Cosmos, identified with light, warmth, and life”. Yin is “the principle of darkness, cold, and death, standing in the universe diametrically opposite to Yang”.46 The chief source of Yang is the sun, which gives forth “shen” or “soul substance”; the chief source of Yin is the moon. Yang strengthens the vital energy, and is the active principle in various elixirs of life, including, as De Groot notes, “the cock, jade, gold, pearls, and the products of pine and cypress trees”.47

Yin and Yang are controlled by the constellation, the Great Bear, called in China “the Bushel”. In the Shi Ki there is a reference to “the seven stars of the Bushel”, styled “the Revolving Pearls or the Balance of Jasper”, and arrayed “to form the body of seven rulers”. This constellation is “the chariot of the Emperor (of Heaven). Revolving around the pole, it descends to rule the four quarters of the sphere and to separate the Yin and the Yang; by so doing it fixes the four seasons, upholds the equilibrium between the five elements, moves forward the subdivisions of the sphere, and establishes all order in the Universe.”48

An ancient Chinese writer says in this connection that when the handle (tail) of the Bushel (Great Bear) points to the east (at nightfall), it is spring to all the world. When the handle points to the south it is summer, when it points to the west it is autumn, and when it points to the north it is winter. In the Shu King [2 (Part II, Book I) the Great Bear is referred to as “the pearl-adorned turning sphere with its transverse tube of jade”.49 The Polar Star is the “Pivot of the Sky”, which revolves in its place, “carrying round with it all the other heavenly bodies”. In like manner the Taoists taught that “the body of man is carried round his spirit and by it”. The spirit is thus the “Pivot of Jade”. That is why the Pivot of Jade is used in the ritual services of Taoism.50

In Norse-Icelandic mythology the World Mill controls the seasons and the movements of the heavenly bodies. The heavens revolve round the Polar Star, Veraldar Nagli (“the world spike”). Nine giant maids turn the world mill.51

The Babylonians, who were the pioneer astronomers and astrologers of Asia, identified the stable and controlling spirit of the night sky with the Polar Star, which was called “Ilu Sar” (“the god Shar”) or “Anshar” (“Star of the Height” or “Star of the Most High”).52

Isaiah (xiv, 4–14) refers to the supreme star-god when he makes Lucifer declare: “I will ascend unto heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God; I will sit also upon the mount of the congregation, in the sides of the north; I will ascend above the heights of the clouds; I will be the most High”.

Chinese astronomy and the Chinese calendar are undoubtedly of Babylonian origin. The Babylonian god of the Pole Star has not been forgotten. Dr. Edkins once asked a Chinese schoolmaster: “Who is the Lord of heaven and earth?” He replied “that he knew none but the Pole Star,” called in the Chinese language Teen-hwang-ta-te, the great imperial ruler of heaven.53

There is a god and a goddess in the Great Bear. “Among the liturgical works used by the priests of Tao”, says Edkins, “one of the commonest consists of prayers to Towmoo, a female divinity supposed to reside in the Great Bear. A part of the same constellation is worshipped under the name Kwei-sing. A small temple is erected to this deity on the east side of the entrance to Confucian temples, and he is regarded as being favourable to literature.” But the chief god of literature is “Wen-chang”, who is identified with a constellation near the Great Bear which bears his name. He is prayed to by scholars to assist them in their examinations. Temples were erected to him on elevated earthen terraces. “Wen-chang”, says Edkins, “is said to have come down to our world during many generations at irregular intervals. Virtuous and highly-gifted men were chosen from history as likely to have been incarnations of this divinity.”54

The five elements controlled by the Great Bear as it swings round the Polar Star are in China (1) water, (2) fire, (3) wood, (4) metal, and (5) earth. These elements compose what we call Nature. As we have seen, they were placed under the guardianship of animal gods. The White Tiger of the West, for instance, is associated with metal. When, therefore, metal is placed in a grave, a ceremonial connection with the tiger-god is effected. “According to the Annals of Wu and Yueh, three days after the burial of the king, the essence of the element metal assumed the shape of a white tiger and crouched down on the top of the grave.”55 Here the tiger is a protector—a preserver.

Jade being strongly imbued with Yang or “soul substance” was intimately associated with all the gods, and the various colours of jade were connected with the colours of the “airts” and of the heavens and earth. Laufer quotes from the eighteenth chapter of Chou li, which deals with the functions of the Master of Religious Ceremonies:

“He makes of jade the six objects to do homage to Heaven, to Earth, and to the Four Points of the compass. With the round tablet pi of bluish (or greenish) colour, he does homage to Heaven. With the yellow jade tube tsʼung, he does homage to Earth. With the green56 tablet Kuei, he renders homage to the region of the East. With the red tablet chang, he renders homage to the region of the South. With the white tablet in the shape of a tiger (hu), he renders homage to the region of the West. With the black jade piece of semicircular shape (huang) he renders homage to the region of the North. The colour of the victims and of the pieces of silk for these various spirits correspond to that of the jade tablet.”57

The shape, as well as the colours, of the jade symbols was of ritualistic importance.

What would appear to be the most ancient Chinese doctrine regarding the influences or “breaths” that emanated from Nature, and affected the living and the dead, is summed up in the term Fung-shui. “Fung” means wind, and “shui” means “the water from the clouds which the wind distributes over the world”. Certain winds are good, and certain winds are bad.

The importance attached to wind and water appears to be connected with the ancient belief, found in Babylonia and Egypt, that wind is the “breath of life”, the soul, and that water is the source of all life—“the water of life”.

“Fung-shui”, says De Groot, “denotes the atmospherical influences which bear absolute sway over the fate of man, as none of the principal elements of life can be produced without favourable weather and rains.” It also means, he adds, “a quasi-scientific system, supposed to teach men where and how to build graves, temples, and dwellings, in order that the dead, the gods, and the living may be located therein exclusively, or as far as possible, under the auspicious influences of Nature”.58

The controllers of wind and water are the White Tiger god of the West, and the Blue (or green) Dragon god of the East. “These animals”, says De Groot, “represent all that is expressed by the word Fung-shui, viz., both æolian and aquatic influences, Confucius being reputed to have said that ‘the winds follow the tiger’, and the dragon having, since time immemorial, in Chinese cosmological mythology played the part of chief spirit of water and rain.”59

When the dead were buried it was considered necessary, according to Fung-shui principles, to have graves facing the south, and the Dragon symbol on the left (east) side of the coffin, and the Tiger symbol on the right (west) side, while the Red Bird of the south was on the front, and the Black Tortoise of the north on the back.

These symbols were, so to speak, set amidst natural surroundings that allowed the “free flow” of auspicious influences or “breaths”. A site for a burial-ground was carefully selected, due account being taken of the configurations of the surrounding country and the courses followed by streams.60

Not only graves, but houses and towns, were so placed as to secure the requisite balance between the forces of Nature. De Groot notes that Amoy is reputed by Chinese believers of the Fung-shui system to owe its prosperity to two knolls flanking the inner harbour, called “Tiger-head Hill” and “Dragon-head Hill”. Canton is influenced by the “White clouds”, a chain of hills representing the Dragon on one side of its river, and by undulating ground opposite representing the Tiger. “Similarly”, he says, “Peking is protected on the north-west by the Kin-shan or Golden Hills, which represent the Tiger and ensure its prosperity, together with that of the whole empire and the reigning dynasty. These hills contain the sources of a felicitous watercourse, called Yu-ho or ‘Jade River’, which enters Peking on the north-west, and flows through the grounds at the back of the Imperial Palace, then accumulates its beneficial influences in three large reservoirs or lakes dug on the west side, and finally flows past the entire front of the inner palace, where it bears the name of the Golden Water.”61

Here we find jade and gold closely associated in the Fung-shui system.

As we have seen, white jade was used when the Tiger god of the West was worshipped; it is known as “tiger jade”; a tiger was depicted on the jade symbol. To the Chinese the tiger was the king of all animals and “lord of the mountains”, and the tiger-jade ornament was specially reserved for commanders of armies. The male tiger was, among other things, the god of war, and in this capacity it not only assisted the armies of the emperors, but fought the demons that threatened the dead in their graves.

There are traces in China of a tigress shape of the goddess of the West. Laufer refers to an ancient legend of the country of Chu, which tells of a prince who in the eighth century B.C. married a princess of Yün. A son was born to them and named Tou Po-pi. The father died and the widow returned to Yün, where Tou Po-pi, in his youth, had an intrigue with a princess who bore him a son. “The grandmother ordered the infant to be carried away and deserted on a marsh, but a tigress came to suckle the child. One day when the prince of Yün was out hunting, he discovered this circumstance, and when he returned home terror-stricken, his wife unveiled to him the affair. Touched by this marvellous incident, they sent messengers after the child, and had it cared for. The people of Chʼu, who spoke a language differing from Chinese, called suckling nou, and a tiger they called yü-tʼu; hence the boy was named Nou Yü-tʼu (‘Suckled by a Tigress’). He subsequently became minister of Chʼu.”62

This Far Eastern legend recalls that of Romulus and Remus, who were thrown into the Tiber but were preserved and rescued; they were afterwards suckled by a she-wolf. The Cretan Zeus was suckled, according to one legend, by a sow, and to another by a goat. A Knossian seal depicts a child suckled by a horned sheep. Sir Arthur Evans refers, in this connection, to the legends of the grandson of Minos who was suckled by a bitch; of Miletos, “the mythical founder of the city of that name”, being nursed by wolves.63 Vultures guarded the Indian heroine Shakuntala, the Assyrian Semiramis was protected by doves, while the Babylonian Gilgamesh and the Persian patriarch Akhamanish were protected and rescued at birth by eagles. Horus of Egypt was nourished and concealed by the serpent goddess Uazit, and in his boyhood made friends of wild animals, as did also Bharata, the son of the Indian vulture-guarded Shakuntala. Horus figures in the constellation of Argo as a child floating in a chest or boat like the abandoned Moses, the abandoned Indian Karna, the abandoned Sargon of Akkad, and, as it would appear, Tammuz who in childhood lay in a “sunken boat”. Horus of the older Egyptian legends was concealed on a green floating island on the Nile—the “green bed of Horus”.64

The oldest known form of the suckling legend is found in the Pyramid Texts of Ancient Egypt. When the soul of the Pharaoh went to the Otherworld he was suckled by a goddess or by the goddesses of the north and south. The latter are referred to in the Texts as “the two vultures with long hair and hanging breasts”.65 Here the vultures take the place of the cow-goddess Hathor. In Troy the cow-mother, covered with stars, becomes the star-adorned sow-mother.66 Demeter had a sow form and Athene a goat form, and other goddesses had dove, eagle, wolf, bitch, &c., forms. The Chinese tigress-goddess is evidently a Far Eastern animal form of the Great Mother who suckles the souls of the dead and the abandoned children who are destined to become notables. Thus behind the wind-god, in the Chinese Fung-shui system, we meet with complex ideas regarding the source of the “air of life”, and the source of the food-supply. The Blue Dragon of the East is the Naga form of the Aryo-Indian Indra,67 the rain-controller, the fertilizer, who is closely associated with Vayu, the wind-god; the dragon is the thunderer, too, like Indra. The close association of the tiger- and dragon-gods in the Fung-shui system may account for the custom of decorating jade symbols of the tiger with the thunder pattern.68

In jade-lore, as will be seen, we touch on complex religious beliefs and conceptions not entirely of Chinese origin. Indeed, it is necessary to leave China and investigate the religious systems of more ancient countries to understand rightly Chinese ideas regarding jade as a substitute for gold, pearls, precious stones, &c., and its connection with vegetation and the Great Mother, the source of all life.

It remains with us to deal with Chinese ideas regarding the soul which was protected by jade, the concentrated form of “soul substance”.

The Chinese believed that a human being had two souls. One was the Kwei, that is the soul which partook of the nature of the element Yin and returned to the earth from which it originally came;69 the other soul was the shen which partook of the element Yang. When the shen is in the living body, it is called Khi or “breath”; after death “it lives forth as a refulgent spirit, styled ming”. The other soul, called Kwei, is known as the pʼoh during life; after death it lives on in the grave beside the body, which is supposed to be protected against decay by the jade, gold, pearls, shells, &c., and the good influences “flowing” from east and west.

The shen, like the cicada, may also dwell for a time in the grave or in the gravestone before it rises on wings to the Sky Paradise, or passes to the Western Paradise or the Eastern “Islands of the Blest”. Ancient local and tribal beliefs and beliefs imported at different periods from different culture centres were evidently fused in China, and we consequently meet with a variety of ideas regarding the destiny of the shen. “Departed souls”, says De Groot, “are sometimes popularly represented as repairing to the regions of bliss on the back of a crane.”70 The soul may sail to the Western Paradise in a boat. “Thou hast departed to the West, from whence there is no returning in the barge of mercy”, runs an address to the corpse.70 Here we have the Ra-boat of Egypt conveying the soul to the Osirian Paradise. As has been shown, souls sometimes departed on the backs of dragons, or rose in the air towards cloudland, there to sail in boats or ride on the backs of birds or kirins, or reached the moon or star-land by climbing a gigantic tree. Belief in transmigration of souls can also be traced in China, the result apparently of the importation of pre-Buddhist as well as Buddhist beliefs from India.

The living performed ceremonies to assist the soul of the dead on its last journey. Priests chanted:

I salute Ye, Celestial Judges of the three spheres constituting the higher, middle, and lower divisions of the Universe, and Ye, host of Kings and nobles of the departments of land and water and of the world of men! Remember the soul of the dead, and help it forward in going to the Paradise of the West.71

Egyptian, Babylonian, and Indian ideas regarding the Western Paradise are here significantly mingled.

During life the soul might leave the body for a period, either during sleep or when one fainted suddenly.

This belief is widespread. The soul, in folk-stories, is sometimes seen, as in Scotland, as a bee, or bird, or serpent, as in Norway as an insect or mouse, as in Indonesia and elsewhere as a worm, snake, butterfly, or mouse, and even, as in different countries, as deer, cats, pigs, crocodiles, &c. Chinese beliefs regarding souls as butterflies, cicadas, &c., have already been referred to.

The wandering soul could be “called back” by repeating the individual’s name. In China, even the dead were called back, and the ceremony of recalling the soul is prominent in funeral rites, as De Groot shows.72 Peoples as far separated as the Mongolian Buriats and the inhabitants of England, Scotland, and Ireland believed that ghosts could be enticed to return to the body.73 The “death-howl” in China and Egypt, and elsewhere, is evidently connected with this ancient belief.

Of special interest is the evidence regarding Korean customs and beliefs. Mrs. Bishop writes: “Man is supposed to have three souls. After death one occupies the tablet, one the grave, and one the unknown. During the passing of the spirit there is complete silence. The under-garments of the dead are taken out by a servant, who waves them in the air, and calls him by name, the relations and friends meantime wailing loudly. After a time the clothes are thrown upon the roof.” When a man dies, one of his souls is supposed to be seized and carried to the unknown and placed on trial before the Ten Judges, who sentence it “either to ‘a good place’ or to one of the manifold hells”.74

Professor Elliot Smith, reviewing the Chinese ideas regarding the two souls, comes to the conclusion that “the early Chinese conceptions of the soul and its functions are essentially identical with the Egyptian, and must have been derived from the same source”.75 As the Chinese have the shen and the Kwei, so had the Egyptians the Ka and the ba. The Ka was the spirit of the placenta, “which was accredited with the attributes of the life-giving and birth-promoting Great Mother and intimately related to the moon and the earliest totem”.76 In China the beliefs and customs connected with the placenta and the moon are quite Egyptian in character.77

Even in the worship of ancestors in China one can trace the influence of Ancient Egyptian ideas. When the Pharaoh died, he was identified with the god. King Unis, in the Pyramid Texts, becomes Osiris, who controls the Nile. “It is Unis”, we read, “who inundates the land.” Pepi I, in like manner, supplanted the god, and he is addressed as Osiris, as is also King Mernere—“Ho this Osiris, King Mernere!” runs a Pyramid Text.78 The sun-god Ra was similarly supplanted by his son, the dead Pharaoh.

The souls of Chinese ancestors, who passed to the Otherworld, became identified with the deities who protected households. Emperors became, after death, emperors in heaven and their souls were the deified preservers of their dynasties. Clan and tribal ancestors were protectors of their clans and tribes, and families were ever under the care of the souls of their founders. The belief became deeply rooted in China that the ancestral soul exercised from generation to generation a beneficent influence over a home. It is not surprising to find, therefore, that gods are exceedingly numerous in China, and that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish an ancestor from a god and a god from an ancestor. The State religion was something apart from domestic religion. Emperors worshipped the deities that controlled the nation’s destinies, and families worshipped the deities of the household.

Local and imported beliefs were fused and developed on Chinese soil, and when, in time, Buddhism was introduced it was mixed with pre-existing religious systems. Chinese Buddhism is consequently found to have local features that distinguish it from the Buddhism of Tibet, Burmah, and Japan, in which countries there was, in like manner, culture-mixing.

Beliefs connected with jade, which date back to the time when the jade fished from the rivers of Chinese Turkestan was identified with pearls and gold, were similarly developed in China. At first the jade was used to assist birth and to cure diseases. It likewise brought luck, being an object that radiated the influence of the All-Mother. As the living had their days prolonged and their youth revived by jade, so were the dead preserved from decay by the influence of the famous mineral. The custom ultimately obtained of eating jade, as has already been noted in these pages. Ground jade or “pure extract of jade” was not only supposed to promote longevity, but to effect a ceremonial connection between the worshipper and the spirits or deities. In the Chou li it is stated that “when the Emperor purifies himself by abstinence, the chief in charge of the jade works prepares for him the jade which he is obliged to eat”.79 It is explained by commentators that “the emperor fasts and purifies himself before communicating with the spirits; he must take the pure extract of jade; it is dissolved that he may eat it”. Jade was also pounded with rice as food for the corpse. “A marvellous kind of jade”, says Laufer, “was called Yü ying, ‘the perfection of jade’,” which ensured eternal life. “In 163 B.C. a jade cup of this kind was discovered on which the words were engraved ‘May the sovereign of men have his longevity prolonged’.” Immortality was secured by eating from jade bowls, or, as we have seen, by drinking dew from a jade bowl.80

As has been shown, the Great Mother created jade for the benefit of mankind, and “the spirit of jade is like a beautiful woman”.81 Jade was also “the essence of the purity of the male principle”.82

Apparently the god who was husband and son of the Great Mother was connected with jade. The Mother was the life-giver, and the son, as Osiris, was “the imperishable principle of life wherever found”.83 If men died, the seed of life in the body was preserved by jade amulets; the plants might shed their leaves, but the life of the plants was perpetuated by the spirit of jade. “In the second month”, says The Illustrated Mirror of Jade, “the plants in the mountains receive a brighter lustre. When their leaves fall, they change into jade.”84 The mountain plants in question appear to be the curative herbs that contained, like jade, the elixir of life, and the chief of these plants was the ginseng (mandrake), an avatar of the Great Mother. The plant, or ground jade, or food or moisture from the jade vessel renewed youth and prolonged life. All the elixirs were concentrated in jade; the vital principle in human beings and plants was derived from and preserved by jade.

It is of special interest to find that the Chinese Nu Kwa who caused the flood to retreat was the creator of the jade which protected mankind and ensured longevity by preserving the seed or shen of life, being impregnated with Yang, the male principle. In Babylonia, the seed of mankind was preserved during the flood by the nig-gil-ma.

In the Sumerian version of the Creation legend, the three great gods Anu, Enlil, and Enki, assisted by the Great Mother goddess Ninkharasagga, first created mankind, then the nig-gil-ma, and lastly the four-legged animals of the field. The mysterious nig-gil-ma is referred to in the story of the Deluge as “Preserver of the seed of mankind”, while the ship or ark is “Preserver of Life”, literally “She that preserves life”. A later magical text refers to the creation after that of mankind and animals of “two small creatures, one white and one black”. Man and animals were saved from the flood and the nig-gil-ma played its or their part “in ensuring their survival”.

Leonard W. King, who has gathered together the surviving evidence regarding the mysterious nig-gil-ma85 points out that the name is sometimes preceded by “the determinative for ‘pot’, ‘jar’, or ‘bowl’ ”, and is identical with the Semitic word mashkhalu. In the Tell-el-Amarna letters there are references to a mashkhalu of silver and a mashkhalu of stone (a silver vessel and a stone vessel). The nig-gil-ma may be simply a “jar” or “bowl”. “But”, says Mr. L. King, “the accompanying references to the ground, to its production from the ground, and to its springing up … suggest rather some kind of plant; and this, from its employment in magical rites, may also have given its name to a bowl or vessel which held it. A very similar plant was that found and lost by Gilgamesh, after his sojourn with Ut-napishtim86; it too had potent magical power, and bore a title descriptive of its peculiar virtue of transforming old age to youth.” The nig-gil-ma may therefore be a plant, a ship, a stone bowl or jar, or a vessel of silver (the moon metal). If we regard it as a symbol or avatar of the mother-goddess it was any of these things and all of these things—the Mother Pot, the inexhaustible womb of Nature, the Plant of Life containing “soul substance”, the red clay, the moon-silver, or, as in China, the jade of which the sacred vessel was made. The Great Mother’s herb-avatar was the ginseng (mandrake), as in the Egyptian Deluge story it was the red earth didi from Elephantine placed in the beer prepared for the slaughtering goddess Hathor-Sekhet as a surrogate of blood and a soporific drink; the mixture was “the giver of life”, the red aqua vitae, like the red wine and the juice of red berries in different areas.87 The mandrake was the didi of southern Europe and of China. Dr. Rendel Harris shows that the early Greek magicians and doctors referred to the male mandrake, which was white, and the female mandrake, which was black. The black mandrake was personified as the Black Aphrodite.88

The Babylonian reference in a magical text to the nig-gil-ma as “two small creatures, one white and one black” is therefore highly significant. Apparently, like jade, the nig-gil-ma symbolized “the male principle”, and “the spirit” of “a beautiful woman”. Thus mandrake (ginseng), the Plant of Life, red earth, jade, the pearl and the pot or jar or bowl, and the Deluge ship, and the ship of the sun-god, were forms, avatars, or manifestations of the Great Mother who preserved the seed of mankind and the elixir of life—in the Pot it grew the Plant of Life, and from it could be drunk the dew of life, the water of life, plant and water being impregnated with the “spirit” of jade. Jade-lore is of highly complex character because, as has been indicated, the early instructors of the Chinese attached to the mineral the Egypto-Babylonian doctrines regarding the Great Mother and her shells, pearls, precious stones, gold, silver and copper, herbs, trees, cereals, red earth, &c. The Babylonian evidence regarding the nig-gil-ma as a herb, and as a silver or stone jar, pot, or cup, in which was preserved the seed of mankind (“soul substance”) may explain why in the Chinese Deluge myth there is no ark or ship. The goddess provided jade instead of a boat and she created dragons to control the rain-supply, so that the world might not again suffer from the effects of a flood.

The virtues of jade were shared to a certain degree by rhinoceros horn, which, as we have seen, was reputed to shine by night.

Laufer has gathered together sufficient evidence to prove that the rhinoceros was one of the wild animals known in ancient China.89 A hero of the Chou Dynasty, who subdued rebels and established peace throughout the Empire, “drove away also the tigers, leopards, rhinoceroses and elephants—and all the people were greatly delighted”.90 A native writer says: “To travel by water and not avoid sea-serpents and dragons—this is the courage of a fisherman. To travel by land and not avoid the rhinoceros and the tiger—this is the courage of hunters.” In ancient times certain of the lords attending on the emperor had a tiger symbol on each chariot wheel, while other lords had on their wheels crouching rhinoceroses.91 Laufer expresses the view that “the strong desire prevailing in the epoch of the Chou for the horn of the animal (rhinoceros) which was carved into ornamental cups, and for its valuable skin, which was worked up into armour, had … contributed to its final destruction.”92 The rhinoceros-horn cups were used, like jade cups, chiefly for religious purposes. Rice-wine was drunk from them when vows were made, and from them were poured libations to ancestors. The animal’s skin was used not only for armour, because of its toughness and durability, but because the rhinoceros was a longevity animal, and a form of the god of longevity (shou-sing). It was used, too, for the coffin of the “Son of Heaven” (the Emperor). “The innermost coffin was formed by hide of water buffalo and rhinoceros.” This case was enclosed in white poplar timber and the two outer cases were of catalpa wood.93 The jade coffin was similarly a protecting life-giver.

As there were black and white nig-gil-ma, and black and white deities, so were there black and white rhinoceroses and black and white elephants. Gautama Buddha entered his mother’s right side “in the form of a superb white elephant”.94

The water-rhinoceros had “pearl-like armour” (a significant comparison when it is remembered that pearl-lore and jade-lore are so similar), but not the mountain rhinoceros. It was the horn of the male animal that had special virtues. The markings on it included a red line, which was a result of his habit of gazing at the moon; the spots were stars. As the animal was connected with the “material sky”, the horn was impregnated with the Yang principle. A horn that “communicated with the sky” was of the “first quality”. Laufer quotes the statement: “If the horn of the rhinoceros ‘communicating with the sky’ emits light, so that it can be seen by night, it is called ‘horn shining at night’ (ye ming si): hence it can communicate with the spirits and open a way through the water”. A man who carried in his mouth a piece of rhinoceros horn found, it was alleged, on diving into the sea, that the water gave way so as to allow a space for breathing.95 The pearl-fishers may therefore have used the magic horn, believing that it protected and assisted them.

It is recorded of a horn presented to an emperor of the Tʼang Dynasty that “at night it emitted light so that a space of a hundred paces was illuminated. Manifold silk wrappers laid around it could not hide its luminous power. The emperor ordered it to be cut into slices and worked up into a girdle; and whenever he went out on a hunting expedition, he saved candle light at night.” With the aid of the horn it was possible “to see supernatural monsters in water”.96

There was warm rhinoceros horn and cold rhinoceros horn, as there was warm jade and cold jade. A Chinese work of the eighth century mentions “cold-dispelling rhinoceros horn (pi han si), whose colour is golden.97… During the winter months it spreads warmth which imparts a genial feeling to man.” Another work speaks of “heat-dispelling rhinoceros horn (pi shu si).… During the summer months it can cool off the hot temperature.” Girdles of “wrath-dispelling” horn caused men “to abandon their anger”; hair-pins, combs, &c., were made from “dust dispelling” horn. Rhinoceros horn had, like jade, healing properties. A fourth-century Chinese writer tells that “the horn can neutralize poison because the animal devours all sorts of vegetable poisons with its food”. Chinese drug stores still stock shavings of the horn to cure fever, smallpox, ophthalmia, &c.98 According to S. W. Williams99 “a decoction of the horn shavings is given to women just before parturition and also to frighten children”. A medicine is prepared from rhinoceros skin, too. Laufer states that “the skin, as well as the horn, the blood, and the teeth, were medicinally employed in Cambodja, notably against heart diseases.… In Japan rhinoceros horn is powdered and used as a specific in fever cases of all kind.” Dragon bones were used in like manner in China. It is of importance to note that the rhinoceros horn derived its healing qualities because the animal fed on plants and trees provided with thorns.100 Like the dragon, the rhinoceros had an intimate connection with certain plants; like the ginseng-devouring goat, it carried in its blood the virtue of the plants and herbs it devoured. In Tibet and China the rhinoceros became confused with the stag, antelope, and goat with one horn. It was the prototype of the unicorn. In India and Iran it was confused with the horse. There is in Chinese lore a “spiritual rhinoceros (ling si)” with the body of an ox, the hump of a zebu, cloven feet, the snout of a pig, and a horn in front.101 It may be that in ancient times the lore connected with the hippopotamus was transferred by the searchers for pearls, precious stones, and metals to the Chinese “water-rhinoceros”. Like the composite wonder-beast in the Osirian hall of judgment, which tore the unworthy soul to pieces, the rhinoceros had its place in judicial proceedings in China. In its goat form it solved a difficult case when Kas Yas administered justice by butting the guilty party and sparing the innocent.102

The importance attached to jade in prehistoric Europe raises an interesting problem. Jade artifacts have been found associated with the Swiss lake-dwellings, and at “Neolithic sites” in Brittany and Ireland, as well as in Malta and Sicily, and other parts of Europe. Schliemann found votive axes of green and white jade (nephrite) in the stratum of the first city of Troy. It was believed at the time that the European jade artifacts had been imported from the borders of China, and Professor Fischer expressed the wish “that before the end of his life the fortune might be allotted to him of finding out what people brought them to Europe”.103 Professor Max Muller believed that the Aryans were the carriers of jade. “If”, he wrote, “the Aryan settlers could carry with them into Europe so ponderous a tool as their language, without chipping a single facet, there is nothing so very surprising in their having carried along and carefully preserved from generation to generation so handy and so valuable an instrument as a scraper or a knife, made of a substance which is Aere perennuis”.104

After a prolonged search, European scientists have located nephrite (jade proper) or jadeite in situ in Silesia, Austria, North Germany, Italy, and among the Alps. “A sort of nephrite workshop was discovered in the vicinity of Maurach (Switzerland), where hatchets chiselled from the mineral and one hundred and fifty-four pieces of cuttings were found.”105

Laufer writes in this connection: “If we consider how many years, and what strenuous efforts it required for European scientists to discover the actual sites of jade in Central Europe, which is geographically so well explored, we may realize that it could not have been quite such an easy task for primitive man to hunt up these hidden places”. Laufer thinks that in undertaking to overcome the difficulties experienced in discovering jade in Europe, early man “must have been prompted by a motive pre-existing and acting in his mind; the impetus of searching for jade he must have received somehow from somewhere.… Nothing”, he says, “could induce me to believe that primitive man of Central Europe incidentally and spontaneously embarked on the laborious task of quarrying and working jade. The psychological motive for this act must be supplied.… From the standpoint of the general development of culture in the Old World there is absolutely no vestige of originality in the prehistoric cultures of Europe which appear as an appendix to Asia.”106

Apparently the “psychological motive” for searching for jade in China and Europe came from the Khotan area in Chinese Turkestan, whence jade was carried to Babylonia during the Sumerian period. It is probable that bronze was first manufactured in the jade-bearing area of Asia, and that the people who carried “the knowledge of bronze-making into Europe”, as Professor Elliot Smith suggests, “also introduced the appreciation of jade”. Laufer comments in this connection: “Originality is certainly the rarest thing in the world, and in the history of mankind the original thoughts are appallingly sparse. There is, in the light of historical facts and experience, no reason to credit the prehistoric and early populations of Europe with any spontaneous ideas relative to jade.” After receiving jade and adopting the beliefs attached to it, they set out to search for it, and found it in Europe.

The polished axe pendants of jade found in Malta were evidently charms. Among the Greeks jade was “the kidney stone”; it cured diseases of the kidneys. The Spaniards brought jade or jadeite from Mexico, and called it “the loin stone” (piedra de hijada). Sir Walter Raleigh introduced it into England, and used the Spanish name from which “jade” is derived.

Red, green, blue, white, grey, and black jade were used, by reason of their colours, for various deities in China, and to indicate the rank of officials. “White jade, considered the most precious, was the privileged ornament of the emperor; jade green like the mountains was reserved for the princes of the first and second ranks; water-blue jade was for the great prefects; the heir apparent had a special kind of jade.”107 Mottled jades—some resembling granite—were likewise favoured for a variety of purposes.

Jade played an important part in Chinese rain-getting ceremonies. Dragon jade symbols, decorated with fish-scales, were placed on the altar as offerings and for the purpose of invoking the rain-controlling “composite wonder beast” and god. Sometimes bronze and silver dragon symbols were used. According to Laufer, “the jade image of the dragon remained restricted to the Han period, and was substituted at later ages by prayers inscribed on jade or metal tablets. A survival of the ancient custom”, he adds, “may be seen in the large paper or papier mâché figures of dragons carried around in the streets by festival processions in times of drought to ensure the benefit of rain.”108 In front of these dragons are carried the red ball, which symbolizes the moon, the source of fertilizing moisture—of dew, of rain, and therefore of the streams and rivers that flow to the sea.

Jade links with pearls in the ocean surrounding the world, in which lies a gigantic oyster that gapes after rain falls, and sends forth the gleaming rainbow. The Greek historian, Isidorus of Charace (c. 300 B.C.), referring to the pearl-fishing in the Persian Gulf, relates a story about the breeding of pearls being influenced by thunder-storms.109 The jade ceremonial object, which roused the dragon, had thus indirectly a share in pearl production. Pearls were, as we have seen, likewise produced by dragons, who spat them out during storms. As certain pearls were supposed to be formed by dew that dropped from the moon, it may be that the Chinese gigantic oyster was, when it gaped to send forth the rainbow, receiving the substance of a gigantic pearl from the celestial regions. The life-prolonging and youth-renewing “Red Cloud herb” came into existence during a thunder- and rain-storm.

As we have seen, jade contains, according to Far Eastern belief, the essence of heat as well as of moisture. It contains, too, the essence of cold—not the cold of winter but the coolness desired in hot weather.110 In the Tu yang tsa pien, a Chinese work of the ninth century, it is recorded that the Emperor of China received from Japan “an engraved gobang board of warm jade, on which the game could be played in winter without getting cold, and that it was most highly prized”. It is told in this connection that “thirty thousand li (leagues) east of Japan is the island of Tsi-mo, and upon this island the Ninghia Terrace, on which terrace is the Gobang Player’s Lake. This lake produces the chess-men which need no carving, and are naturally divided into black and white. They are warm in winter, cool in summer, and known as cool and warm jade. It also produces the catalpa-jade, in structure like the wood of the catalpa tree, which is carved into chess-boards, shining and brilliant as mirrors.”111

Jade is, in short, a “luck stone”: the giver of children, health, immortality, wisdom, power, victory, growth, food, clothing, &c. It is “the jewel that grants all desires” in this world and the next, and is therefore connected with all religious beliefs, while it also plays its part as a symbol in the social organization, being the medium through which the mysterious forces of nature exercise their influence in every sphere of human thought and activity.