CHAPTER XVI

MYTHS AND DOCTRINES OF TAOISM

Taoism and Buddhism—The Tao—Taoism and Confucianism—Lao Tze and Osiris—The “Old Boy” Myth—Lao Tze goes West—Kwang Tze—Prince who found the Water of Life—The “Great Mother” in Taoism—Taoism and Egyptian Ptahism—Doctrine of the Logos—Indian Doctrines in China—Taoism and Brahmanism—Metal Searchers as Carriers of Egyptian and Babylonian Cultures—The Tao and Water—The Tao as “Mother of All Things”—Fertilizing Dew and Creative Tears—The Tao and Artemis—The Gate Symbol—Tao and Good Order—The World’s Ages in Taoism—Taoists rendered Invulnerable like Achilles, &c.—The Tao as the Elixir of Life—Breathing Exercises—The Impersonal God—Lao Tze and Disciples deified and worshipped.

There are three religions in China, or, as native scholars put it, “three Teachings”, namely Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. Pure Taoism, as taught by Lao Tze, is, like the Buddhism of its founder, Siddhartha Gautama, metaphysical and mystical. It is similarly based on a vague and somewhat bewildering conception of the origin of life and the universe; it recognizes a creative and directing force which, at the beginning, caused Everything to come out of Nothing. This force, when in action, is called the Tao. It is so called from the time when it began to move, to create, to cause Unity to be. The Tao existed before then, but it was nameless, and utterly incomprehensible. It existed, some writers say, even when there was nothing. Others go the length of asserting that it existed before there was nothing. We can understand what is meant by “nothing”, but we cannot understand what the Nameless was before it was manifested as the Tao.

The Tao is not God; it is impersonal. Taoists must make unquestioning submission to the Tao, which must be allowed to have absolute sway in the individual, in society, in the world at large. Taoism does not, like Buddhism, yearn for extinction, dissolution, or ultimate loss of identity and consciousness in the nebulous Nirvana. Nor does it, like Buddhism, teach that life is not worth living—that it is sorrowful to be doomed to be reborn. Rather, it conceives of a perfect state of existence in this world, and of prolonged longevity in the next. All human beings can live happily if they become like little children, obeying the law (Tao) as a matter of course, following in “the way” (Tao) without endeavouring to understand, or having any desire to understand, what the Tao is. The obedient, unquestioning state of mind is reached by means of Inaction—mental Inaction. The Tao drifts the meritorious individual towards perfection, out of darkness into light. Those who submit to the Tao know nothing of ethical ideals; they are in no need of definite beliefs. It is unnecessary to teach virtue when all are virtuous; it is unnecessary to have rites and ceremonies when all are perfect; it is unnecessary to be concerned about evil when evil ceases to exist. The same idea prevailed among the Brahmanic sages of India, whose Krita or Perfect Age was without gods or devils. Being perfect, the people required no religion.

Confucianism is not concerned with metaphysical abstractions, or with that sense of the Unity of all things and all beings in the One, which is summed up in the term “Mysticism”. It maintains a somewhat agnostic, but not irreligious frame of mind, confessing inability to deal with the spirit world, or to understand, or theorize about, its mysteries. It recognizes the existence of God and of spirits. “Respect the spirits,” said Confucius, “but keep them at a distance.…” He also said: “Wisdom has been imparted to me. If God were to destroy this wisdom (his system of ethics) the generations to come could not inherit it.”

Whether or not Confucius ever heard of the system of Lao Tze is uncertain. If he did, it certainly made no appeal to him. His own system of instruction was intensely practical. It was concerned mainly with ethical and political ideals—with political morality. He was no believer in Inaction. The salvation of mankind, according to his system, could be achieved by strict adherence to the ideals of right living and right thinking, and a robust and vigorous application of them in the everyday life of individuals and the State.

The reputed founder or earliest teacher of Taoism was Lao Tze, about whom little or nothing is known. He is believed to have been born in 604 B.C., and to have died soon after 532 B.C. Confucius was born in 551 B.C., and died in 479 B.C. There are Chinese traditions that the two sages met on at least one occasion, but these are not credited by Western or modern native Chinese scholars. Confucius makes no direct reference to Lao Tze in his writings.

Lao Tze1 means “Old Boy”, as Osiris, in his Libyan form, is said to mean the “Old Man”.2 He was given this name by his followers, because “his mother carried him in her womb for seventy-two years, so that when he was at length cut out of it his hair was already white”. Julius Cæsar was reputed to have been born in like manner; so was the Gaelic hero, Goll MacMorna, who, as we gather from Dunbar, was known in the Lowlands as well as the Highlands; the poet makes one of his characters exclaim,

My fader, meikle Gow mas Mac Morn,

Out of his moderis (mother’s) wame was shorn.

The same legend clings to the memory of Thomas the Rhymer, who is referred to in Gaelic as “the son of the dead woman” (mac na mna marbh), because his mother died before the operation was performed. Shakespeare’s Macduff “was from his mother’s womb untimely ripped”.3

It may be that this widespread birth-story had its origin in Egypt. Plutarch, in his treatise on the Mystery of Osiris and Isis, tells that Set (the ancient god who became a devil) was “born neither at the proper time, nor by the right place”, but that he “forced his way through a wound which he had made in his mother’s side”.

Different forms of the legend are found in China. According to the traditions preserved in the “Bamboo Books”, which are of uncertain antiquity, the Emperor Yao was born fourteen months after he was conceived, the Emperor Yu emerged from his mother’s back, and the Emperor Yin from his mother’s chest. The Aryo-Indian hero, Karna, a prominent figure in the Mahábhárata, emerged from one of his mother’s ears; he was a son of Surya, the sun-god.

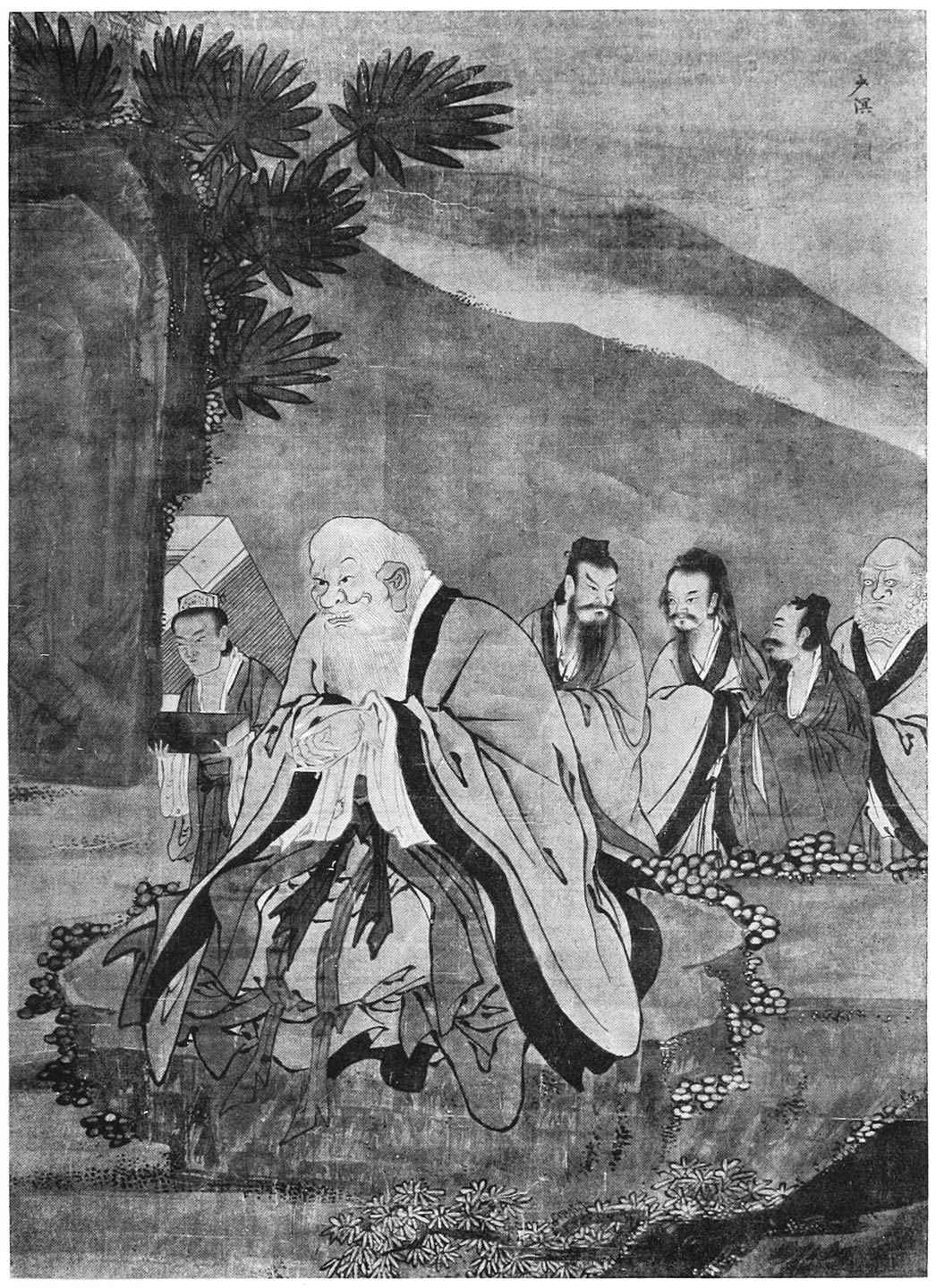

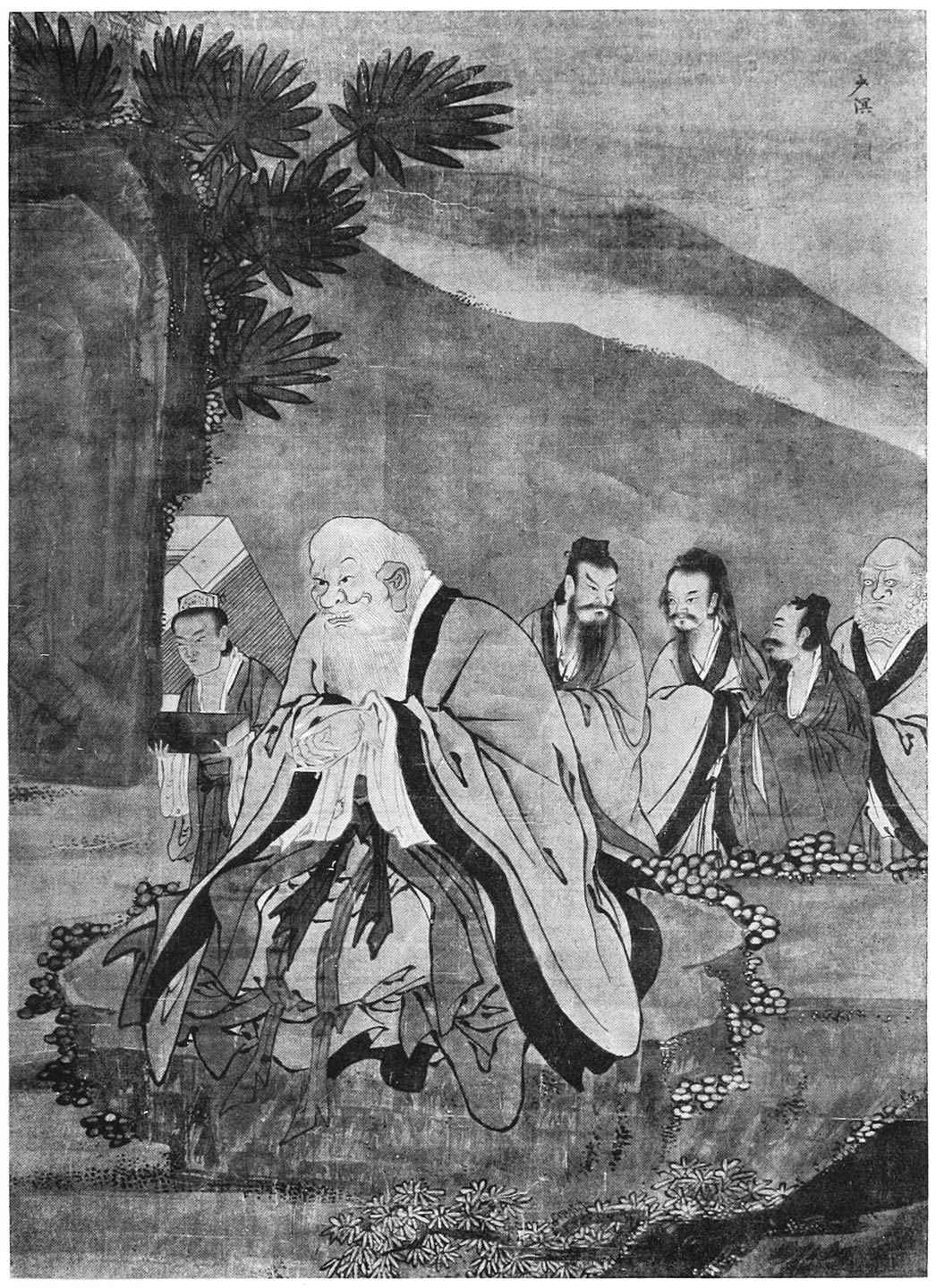

LAO TZE AND DISCIPLES

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

According to Taoist lore (after Buddhism and Taoism were partly fused in China), Lao Tze appeared from time to time in China during the early dynasties in different forms, and with different names. He had the personal knowledge of the decline of the influence of the Tao from the Perfect Age. After Fu-hi and other sovereigns disturbed the harmonies of heaven and earth, “the manners of the people, from being good and simple, became bad and mean”. He came to cleanse the stream of spiritual life at its source, and was ultimately reborn as Lao Tze, under the Plum Tree of Longevity, having been conceived under the influence of a star in the constellation of the Great Bear. Li (plum tree) was his surname.

Lao Tze is said to have held a position in the Royal Library of Kau. When he perceived that the State showed signs of decadence, he resolved to leave the world, like the Indian heroes, Yudhishthira and his brothers. He went westwards, apparently believing, as did Confucius, “that the Most Holy was to be found in the West”. On entering the pass of Hsien-Ku (in modern Ling-pao, Ho-nan province) the Warden, Yin Hsi, a Taoist, welcomed the sage and set before him a dish of tea. Lao Tze sat down to drink tea with his friend. This was the beginning of the tea-drinking custom between host and guest in China.4

Said the Warden, “And so you are going into retirement. I pray you to write me a book before you leave.”

Lao Tze consented, and composed the Tao Teh King,5 which is divided into two parts, and contains over 5000 words.

When he had finished writing, he gave the manuscript to the Warden, bade him farewell, and went on his way. It is not known where he died.

The most prominent of Lao Tze’s disciples was Kwang Tze, who lived in the fourth century B.C. Sze-ma Khien, the earliest Chinese historian of note, who died about 85 B.C., says that Kwang Tze wrote “with purpose to calumniate the system of Confucius and exalt the mysteries of Lao Tze”. But although he wrote much, “no one could give practical application to his teaching”. Other famous Taoist writers were Han Fei Tze, who committed suicide in 233 B.C., and Liu An, prince of Hwai-nan, and grandson of the founder of the Han Dynasty, who took his own life in 122 B.C., having become involved in a treasonable plot.

Another form of the legend is that this prince discovered the Water of Life. As soon as he drank of it, his body became so light that he ascended to the Celestial Regions in broad daylight and was seen by many. As he rose he let fall the cup from which he had drunk. His dogs lapped up the water and followed him. Then his poultry drank from the cup and likewise rose in the air and vanished from sight. Apparently it was not only the poor Indians “with untutored minds” who thought their dogs (not to speak of their hens) would be admitted to the “equal sky”, there to bear them company.

It is generally believed by Oriental scholars that both Taoism and Confucianism are of greater antiquity than their reputed founders. Confucius insisted that he was “a transmitter, not a maker”, and Lao Tze is found to refer to “an ancient”, “a sage”, and “a writer on war”, as if he had been acquainted with writings that have not come down to us.

There is internal evidence in the Taoistic texts of Lao Tze and Kwang Tze that the idea of the Tao had an intimate association in early times with the ancient Cult of the West—the cult of the mother-goddess who had her origin in water. The priestly theorists instructed the worshippers of the Great Mother that at the beginning she came into existence as an egg, or a lotus bloom from which rose the Creator, the sun-god, or that she was a Pot containing water from which all things have come—the pot being the inexhaustible womb of Nature, and the symbol of the Great Mother-goddess.

But they themselves were not satisfied with this myth. They recognized that there was at work at the beginning a force—a law which “opened the way”, a phrase which may have had a physical significance but ultimately became a mystical one. In Chinese Taoism, this force is the Tao which is manifested in order, stability, and rightness; it is Truth.

The Ancient Egyptian philosophers believed, at as remote a time as the Pyramid Texts period (c. 2500 B.C.), that everything had origin in Mind. The Universe was the idea of Ptah, the “opener”; he conceived it in his “Heart” (Mind); when he expressed the idea, the Universe came into existence.

Ptah, the great, is the mind and tongue of the gods.…

It (the mind) is the one that bringeth forth every successful issue.

It is the tongue which repeats the thought of the mind:

It (the mind) was the fashioner of all gods …

At a time when every divine word

Came into existence by the thought of the mind,

And the command of the tongue.6

Although Breasted first thought that this fragment was a survival from the Empire period (c. 1500 B.C.), he has since become convinced, like Erman, that it must, on the basis of orthography, be relegated to the Pyramid Age.

“Is there not here,” Breasted asks, “the primeval germ of the later Alexandrian doctrine of the ‘Logos’?”7

In India Brahma (neuter) was the World Soul, “that subtle essence” which, according to the composers of the Upanishads, exists in everything that is, but cannot be seen. The personal Brahma, as Prajapati, arose, at the beginning, from this impersonal World Soul. “Mind (or Soul, manas),” an Indian sage has declared, “was created from the non-existent. Mind created Prajapati. Prajapati created offspring. All this, whatever exists, rests absolutely on mind.”

Another Indian sage writes:

“At first the Universe was not anything. There was neither sky, nor earth, nor air. Being non-existent, it resolved, ‘Let me be.’ It became fervent. From that fervour smoke was produced. It again became fervent. From the fervour fire was produced. Afterwards the fire became ‘rays’8 and the ‘rays’ condensed into a cloud, producing the sea. A magical formula (Dasahotri) was created. Prajapati is the Dasahotri.”

When the Rev. Dr. Chalmers of Canton translated the Taoist Texts into English in 18689, he wrote: “I have thought it better to leave the word ‘Tao’ untranslated, both because it has given the name to the sect—the Taoists—and because no English word is its exact equivalent. Three terms suggest themselves—‘the Way’, ‘Reason’, and ‘the Word’; but they are all liable to objection. Were we guided by etymology, ‘the Way’ would come nearest to the original, and in one or two passages the idea of a Way seems to be in the term; but this is too materialistic to serve the purpose of a translation. ‘Reason’ again seems to be more like a quality or attribute of some conscious Being than Tao is. I would translate it by ‘the Word’ in the sense of the Logos, but this would be like settling the question which I wish to leave open, viz. what amount of resemblance there is between the Logos of the New Testament and this Tao, which is its nearest representative in Chinese.”

The New Testament doctrine of the Logos may here be reproduced by way of comparison, the quotation being from Dr. Weymouth’s idiomatic translation, which may be compared with the authorized versions:10

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through Him, and apart from Him nothing that exists came into being. In Him was Life, and that Life was the Light of men. The Light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overpowered it.

There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness, in order that he might give testimony concerning the Light—so that all might believe through him. He was not the Light, but he existed that he might give testimony concerning the Light. The true Light was that which illumines every man by its coming into the world. He was in the world, and the world came into existence through Him, and the world did not recognize Him.

The meaning of the word “Tao”, says Max Von Brandt, “has never been explained or understood,” and he adds, “Like the Hellenistic ‘Logos’, it is at once the efficient and the material cause.”11 Professor G. Foot Moore says, “Tao is literally ‘way’; like corresponding words in many languages, ‘course’, ‘method’, ‘order’, ‘norm’.”12 Archdeacon Hardwick13 was “disposed to argue” that the system of Taoism was founded on the idea of “some power resembling the ‘Nature’ of modern speculators. The indefinite expression ‘Tao’ was adopted to denominate an abstract cause, or the initial principle of life and order, to which worshippers were able to assign the attributes of immateriality, eternity, immensity, invisibility.”

Canon Farrar has written in this connection: “We have long personified under the name of Nature the sum total of God’s law as observed in the physical world; and now the notion of Nature as a distinct, living, independent entity seems to be ineradicable alike from our literature and our systems of philosophy.”14

Dr. Legge comments on this passage: “But it seems to me that this metaphorical use of the word ‘nature’ for the Cause and Ruler of it implies the previous notion of Him, that is, of God, in the mind.”15

Dr. Legge notes that in Lao Tze’s treatise “Tao appears as the spontaneously operating cause of all movement in the phenomena of the universe.… Tao is a phenomenon, not a positive being, but a mode of being.”16

Others have rendered Tao as “God”. But “the old Taoists had no idea of a personal God,” says Dr. Legge.

De Groot17 refers to Tao as “the ‘Path’, the unalterable course of Nature,” and adds that the “reverential awe of the mysterious influences of Nature is the fundamental principle of an ancient religious system usually styled by foreigners Tao-ism.”

The idea of the Chinese Tao resembles somewhat that of the Indian Brahma (neuter). Lao Tze says: “It (Tao) was undetermined and perfected, existing before the heaven and the earth. Peaceful was it and incomprehensible, alone and unchangeable, filling everything, the inexhaustible mother of all things. I know not its name, and therefore I call it Tao. I seek after its name and I call it the Great. In greatness it flows on for ever, it retires and returns. Therefore is the Tao great.”

In his chapter “The Manifestation of the Mystery”, Lao Tze says:

“We look at it (Tao), and we do not see it, and we name it ‘the Equable’.

“We listen to it, and we do not hear it, and we name it ‘the Inaudible’.

“We try to grasp it, and do not get hold of it, and we name it ‘the Subtle’.

“With these three qualities, it cannot be made the subject of description; and hence we blend them together and obtain ‘The One’.”

Some scholars, like Joseph Edkins and Victor von Strauss, have contended that Lao Tze was attempting to express the ideas of Jehovah in Hebrew theology. Others incline to the belief that the influence of Indian Brahmanic speculations had reached China at an early period and inaugurated the intuitional teaching found in Lao Tze’s treatise.

The idea of the first cause had arisen in India before the close of the Vedic Age. At the beginning:

There was neither existence nor non-existence,

The Kingdom of air, nor the sky beyond.

What was there to contain, to cover, in—

Was it but vast, unfathomed depths of water?

There was no death there, nor Immortality:

No sun was there, dividing day from night.

Then was there only THAT, resting within itself.

Apart from it, there was not anything.

At first within the darkness veiled in darkness,

Chaos unknowable, the All lay hid.

Till straitway from the formless void made manifest

By the great power of heat was born the germ.18

The Great Unknown was by the later Vedic poets referred to by the interrogative pronoun “What?” (Ka).

In the Indian Khandogya Upanishad, the sage tells a pupil to break open a fruit. He then asks, “What do you see?” and receiving the reply, “Nothing”, says, “that subtle essence which you do not perceive there, of that very essence this great Nyagrodha tree exists. Believe me, my son, that which is the subtle essence, in it all that exists has itself. It is the True. It is self; and thou, my son, art it.”19

The idea of the oneness and unity of all things is the basic principle of mysticism.

There is true knowledge. Learn thou it is this:

To see one changeless Life in all the lives,

And in the Separate, One Inseparable.20

Dr. Legge in his commentary on The Texts of Taoism, asks his readers to mark well the following predicates of the Tao:

“Before there were heaven and earth, from of old, there It was securely existing. From It came the mysterious existence of spirits; from It the mysterious existence of Ti (God). It produced heaven. It produced earth.”21

Lao Tze had probably never been in India, but that passage from his writings might well have been composed by one of the Brahmanic sages who composed the Upanishads.

The explanation may be that in Brahmanism and Taoism we have traces of the influence of Babylonian and Egyptian schools of thought. No direct proof is available in this connection. It is possible, however, that the ancient sages who gave oral instruction to their pupils were the earliest missionaries on the trade-routes. The search for wealth had, as has been shown, a religious incentive. It is unlikely, therefore, that only miners and traders visited distant lands in which precious metals and jewels were discovered. Expeditions, such as those of the Egyptian rulers that went to Punt for articles required in the temples, were essentially religious expeditions. It was in the temples that the demand for gold and jewels was stimulated, and each temple had its workshops with their trade secrets. The priests of Egypt were the dyers, and they were the earliest alchemists22 of whom we have knowledge. Such recipes as are found recorded in the Leyden papyrus were no doubt kept from the common people.

Associated with the search for metals was the immemorial quest of the elixir of life, which was undoubtedly a priestly business—one that required the performance of religious ceremonies of an elaborate character. Metals and jewels, as we have seen, as well as plants, contained the “soul substance” that was required to promote health and to ensure longevity in this world and in the next. It was, no doubt, the priestly prospectors, and not the traders and working miners, who first imparted to jade its religious value as a substitute for gold and jewels.

When the searchers for wealth introduced into India and China the god Ptah’s potter’s wheel they may well have introduced too the doctrine of the Logos, found in the pyramid-age Ptah hymn quoted above, in which the World Soul is the “mind” of the god, and the active principle “the tongue” that utters “the Word”.

If they did so—the hypothesis does not seem to be improbable—it may be that as Buddhism was in India mixed with Naga worship, and was imported into Tibet and China as a fusion of metaphysical speculations and crude idolatrous beliefs and practices, the priestly philosophies of Egypt and Babylonia were similarly associated with the debris of primitive ideas and ceremonies when they reached distant lands. As a matter of fact, it is found that in both these culture centres this fusion was maintained all through their histories. Ptah might be the “Word” to the priests, but to the common people he remained the artisan-god for thousands of years—the god who hammered out the heavens and set the world in order—a form of Shu who separated the heavens from the earth, as did Pʼan Ku in China.

In India and China, as in ancient Egypt, the doctrine of the Logos, in its earliest and vaguest form, was associated with the older doctrine that life and the universe emerged at the beginning from the womb of the mother-goddess, who was the active principle in water, or the personification of that principle.

In one of the several Indian creation myths, Prajapati emerges, like the Egyptian Sun-god Horus, from the lotus-bloom floating on the primordial waters. The lotus is the flower form of the Great Mother, who in Egypt is Hathor.

Another myth tells that after the heat caused the rays to arise, and the rays caused a cloud to form, and the cloud became water, the Self-Existent Being (here the Great Father) created a seed. He flung the seed into the waters, and it became a golden egg. From the egg came forth the personal Brahma (Prajapati).23 Because Brahma came from the waters (Narah), and they were his first home or path (ayana), he is called Narayana.24

Here we have the “path” or “way”, the Chinese Tao in one of its phases.

When the Tao (neuter) became “active”, it did not manifest itself as a Great Father, however, but as a Great Mother. The passive Tao is nameless; the active Tao has a name. Lao Tze’s great treatise, The Tao Teh King, opens:

“The Tao that can be trodden is not the enduring and unchanging Tao.

The name that can be named is not the enduring and unchanging name,

(Conceived of as) having no name, it is the Originator of heaven and earth;

(Conceived of as) having a name, it is the Mother of all things.”25

The creation myths embedded in the writings of Lao Tze are exceedingly vague.

“The Tao produced One; One produced Two; Two produced Three; Three produced All things. All things leave behind them the Obscurity (out of which they have come), and go forward to embrace the Brightness (into which they have emerged), while they are harmonized by the Breath of Vacancy.”26

Another passage seems to indicate that the One, first produced, was the Mother, and that the two produced by her were Heaven and Earth—the god of the sky and the goddess of the earth:

“Heaven and Earth (under the guidance of Tao) unite together and send down the sweet dew, which, without the direction of men, reaches equally everywhere as of its own accord.”27

The fertilizing dew, like the creative tears of Egyptian and Indian deities, gave origin to earth and its plants, and to all living things. But no such details are given by Lao Tze. He is content to suggest that the Tao as “the Honoured Ancestor” appears to have been before God.

In his chapter, “The Completion of Material Forms”, he refers to the female valley spirit. “The valley,” says Legge, “is used metaphorically as a symbol of ‘emptiness’ or ‘vacancy’, and the ‘spirit of the valley’ is ‘the female mystery’—the Tao which is ‘the mother of all things’.”

Chalmers renders Chapter VI as follows:

“The Spirit (like perennial spring) of the Valley never dies. This (Spirit) I call the abyss-mother. The passage of the abyss-mother I call the root of heaven and earth. Ceaselessly it seems to endure, and it is employed without effort.”

Dr. Legge’s rendering is in verse:

The valley spirit dies not, aye the same;

The female mystery thus do we name.

Its gate, from which at first they issued forth,

Is called the root from which grew heaven and earth.

Long and unbroken does its power remain,

Used gently, and without the touch of pain.28

The symbolism of this short chapter is of special interest, and seems to throw light on the origin of the myths that were transformed by Lao Tze into philosophical abstractions. We find the “female mystery” or “abyss mother” is at once a gate (or passage) and a “root”. The Greek goddess Artemis was both. She was the guardian of the portals, and was herself the portals; she was the giver of the mugwort (the Chinese knew it), and was herself the mugwort (Artemisia), as Dr. Rendel Harris has shown.29 She opened the gate of birth as the goddess of birth, her “key” being the mugwort, and she opened the portal of death as the goddess of death. As the goddess of riches she guarded the door of the treasure-house, and she possessed the “philosopher’s stone”, which transmuted base metals into gold. Artemis was a form of the Egyptian Hathor, Aphrodite being another specialized form. Hathor was associated with the lotus and other water plants, and was Nub, the lady of gold, who gave her name to Nubia; she was the goddess of miners, and therefore of the Sinaitic peninsula; she was the “gate” of birth and death. The monumental gateways of Egypt, India, China, and Japan appear to have been originally goddess portals.30

The goddess of the early prospectors and miners was, as has been said, a water-goddess. In the writings of Lao Tze, his female and active Tao, “the Mother of all Things”, is closely associated with water. The chapter entitled “The Placid and Contented Nature” refers to water, and water as “an illustration of the way of the Tao, is”, Dr. Legge comments, “repeatedly employed by Lao Tze”.

“The highest excellence is like (that of) water. The excellence of water appears in its benefiting all things.”31

Lao Tze, dealing with “The Attribute of Humility”, connects “water” with “women”:

“What makes a great state is its being (like a low-lying down-flowing stream); it becomes the centre to which tend (all the small states) under heaven.

“(To illustrate from) the case of all females:—the female always overcomes the male by her stillness.”32

Water is soft, but it wears down the rocks.

“The softest thing in the world dashes against and overcomes the hardest; that which has no (substantial) existence enters where there is no crevice.”33

The Tao acts like water, and (The Tao) “which originated all under the sky is”, Lao Tze says, “to be considered as the mother of all of them. When the mother is found, we know what her children should be.”34

A passage which has puzzled commentators is,

“Great, it (the Tao) passes on (in constant flow). Passing on, it becomes remote. Having become remote, it returns. Therefore the Tao is great.”35

The reference may be to the circle of water which surrounds the world. It is possible Lao Tze had it in mind, seeing that he so often compares the action of the Tao to that of water—the Tao that produces and nourishes “by its outflowing operation”.

Like “soul substance”, the Tao is found in all things that live, and in all things that exercise an influence on life. The Tao is the absolute, or, as the Brahmanic sages declared, the “It” which cannot be seen—the “It” in the fruit of the tree, the “It” in man. Lao Tze refers to the “It” as the “One”.

In his chapter, “The Origin of the Law”, he writes:

The things which from of old have got the One (the Tao) are:

Heaven, which by it is bright and pure;

Earth endowed thereby firm and sure;

Spirits with powers by it supplied;

Valleys kept full throughout their void;

All creatures which through it do live;

Princes and Kings who from it get

The model which to all they give.36

The Tao may produce and nourish all things and bring them to maturity, but it “exercises no control over them”.37

Man must begin by taking control of himself: he must make use of the light that is within him. The wise man “does not dare to act” of his accord. When he has acted so that he reaches a state of inaction, the Tao will then drift him into a state of perfection. He must guard the mother (Tao) in himself by attending to the breath. “The management of the breath,” says Dr. Legge, “is the mystery of the esoteric Buddhism and Taoism.”38 “When one knows,” Tao Tze has written, “that he is his mother’s child, and proceeds to guard (the qualities of) the mother that belongs to him, to the end of his life he will be free from peril. Let him keep his mouth closed, and shut up the portals (of his nostrils), and all his life he will be exempt from laborious exertion.”39

By giving “undivided attention to the breath” (the vital breath), and bringing it “to the utmost degree of pliancy”, he “can become as a (tender) babe. When he has cleansed away the most mysterious sights (of his imagination), he can become without a flaw.”40

The doctrine of Inaction pervades the teaching of Lao Tze, which is quite fatalistic. Salvation depends on the individual and the state allowing the Tao to “flow” freely.

“If the Empire is governed according to Tao, evil spirits will not be worshipped as good ones.

“If evil spirits are not worshipped as good ones, good ones will do no injury. Neither will the Sages injure the people. Each one will not injure the other. And if neither injures the other, there will be mutual profit.”

A native commentator writes in this connection:

“Spirits do not hurt the natural. If people are natural, spirits have no means of manifesting themselves, and if spirits do not manifest themselves, we are not conscious of their existence as such. Likewise, if we are not conscious of the existence of spirits as such, we must be equally unconscious of the existence of inspired teachers as such; and to be unconscious of the existence of spirits and of inspired teachers is the very essence of Tao.”41

The scholarly sage thus reached the conclusion that it is a blessed thing to know nothing, to be ignorant. Good order is necessary for the workings of the Tao, and good order is secured by abstinence from action, and by keeping the people in a state of simplicity and ignorance, so that they may be restful and child-like in their unquestioning and complete submission to the Tao. “The state of vacancy,” says Lao Tze, “should be brought to the utmost degree.… When things (in the vegetable world) have displayed their luxuriant growth, we see each of them return to its root. This returning to their root is what we call the state of stillness.”42

There would be no virtues if there were no vices, no robberies if there were no wealth.

“If,” the Taoists argued, “we would renounce our sageness and discard our wisdom, it would be better for the people a hundredfold. If we could renounce our benevolence and discard our rightness, the people would again become filial and kindly. If we could renounce our artful contrivances and discard our scheming for gain, there would be no thieves and robberies.”43

Here we meet with the doctrine of the World’s Ages, already referred to. Men were perfect to begin with, because, as Lao Tze says, “they did not know they were ruled”. “In the age of perfect virtue,” Kwang Tze writes, “they attached no value to wisdom.… They were upright and correct, without knowing that to be so was righteousness; they loved one another, without knowing that to do so was benevolence; they were honest and leal-hearted without knowing that it was loyalty; they fulfilled their engagements, without knowing that to do so was good faith; in their simple movements they employed the services of one another, without thinking that they were conferring or receiving any gift. Therefore their actions left no trace, and there was no record of their affairs.”

To this state of perfection, Lao Tze wished his fellow-countrymen to return.

That the idea of the Tao originated among those who went far and wide, searching for the elixir of life, is suggested by Lao Tze’s chapter, “The Value Set on Life”. He refers to those “whose movements tend to the land (or place) of death”, and asks, “For what reason?” The answer is, “Because of their excessive endeavours to perpetuate life”.

He continues:

“But I have heard that he who is skilful in managing the life entrusted to him for a time travels on the land without having to shun rhinoceros or tiger, and enters a host without having to avoid buff coat or sharp weapon. The rhinoceros finds no place in him into which to thrust its horn, nor the tiger a place in which to fix its claws, nor the weapon a place to admit its point. And for what reason? Because there is in him no place of death.”44

It would appear that Lao Tze was acquainted not only with more ancient writers regarding the Tao, but with traditions regarding heroes resembling Achilles, Siegfried, and Diarmid, whose bodies had been rendered invulnerable by dragon’s blood, or the water of a river in the Otherworld; or, seeing that each of these heroes had a spot which was a “place of death”, with traditions regarding heroes who, like El Kedir, plunged in the “Well of Life” and became immortals, whose bodies could not be injured by man or beast. The El Kedirs of western Asia and Europe figure in legends as “Wandering Jews” or invulnerable heroes, including those who, like Diarmid, found the “Well of Life”, and those who had knowledge of charms that rendered them invisible or protected them against wounds. The Far Eastern stories regarding the inhabitants of the “Islands of the Blest”, related in a previous chapter, may be recalled in this connection. Having drunk the waters of the “Well of Life” and eaten of the “fungus of immortality”, they were rendered immune to poisons, and found it impossible to injure themselves. When, therefore, we find Lao Tze referring to men who had no reason to fear armed warriors or beasts of prey, it seems reasonable to conclude that these were men who had found and partaken of the elixir of life, or had accumulated “stores of vitality” by practising breathing exercises and drinking charmed water, or by acquiring “merit”, like the Indian ascetics who concentrated their thoughts on Brahma (neuter).

In the chapter, “Returning to the Root”, in his Tao Teh King, Lao Tze appears to regard the Tao as a preservative against death. He who in “the state of vacancy” returns to primeval simplicity and perfectness achieves longevity through the workings of the Tao.

“Possessed of the Tao, he endures long; and to the end of his bodily life is exempt from all danger of decay.”45

Here the Tao acts like the magic water that restores youth. It is “soul substance”, and is required by the Chinese gods as Idun’s apples are required by the Norse gods. Says Lao Tze:

“Spirits of the dead receiving It (Tao) become divine; the very gods themselves owe their divinity to its influence; and by It both heaven and earth were produced”.46

There were floating traditions in China in Lao Tze’s time regarding men who had lived for hundreds of years. One was “the patriarch Phăng”, who is referred to by Confucius47 as “our old Phăng”. It was told that “at the end of the Shang Dynasty (1123 B.C.) he was more than 767 years old, and still in unabated vigour”. We read that during his lifetime he lost forty-nine wives and fifty-four sons; and that, after living for about 1500 years, he died and left two sons, Wu and I, who “gave their names to the Wu-i or Bu-i Hills, from which we get our Bohea tea”.48

Kwang Tze refers to Phăng. But instead of telling that he had discovered and partaken of the elixir of life, as he must have done in the original story, he says that he “got It (the Tao), and lived on from the time of the lord Yu to that of the five chiefs”.49

Others who got It (the Tao) in like manner were, according to Kwang Tze, the prehistoric Shih-wei who “adjusted heaven and earth”, Fu-hsi who “by It penetrated to the mystery of the maternity of the primary matter”, the sage Hwang-Ti who “by It ascended the cloudy sky”, Fu Yueh, chief minister of Wu-ting (1324–1264 B.C.), who got It and after death mounted to the Eastern portion of the Milky Way, where, riding on Sagittarius and [32]Scorpio, he took his place among the stars. Various spirits “imbibed” It likewise and owed their power and attributes to It (the Tao).50

Kwang Tze tells that a man once addressed a Taoist sage, saying, “You are old, sir, while your complexion is like that of a child; how is it so?”

The reply was, “I have become acquainted with the Tao”.51

Here the Tao is undoubtedly regarded as the elixir of life—as “soul substance” that renews youth and promotes longevity. It was not, however, a thing to eat and drink—the “plant of life” or “the water of life”—but an influence obtained like the spiritual power, the “merit”, accumulated by the Brahmanic hermits of India who practised “yogi”. As the mystery of creation was repeated at birth when a new soul came into existence, so did the Tao create new life when the devotee reached the desired state of complete and unquestioning submission to its workings.

There were some Taoists who, like the Brahmanic hermits, sought refuge in solitary places and endeavoured to promote longevity by management of the breath, adopting what Mr. Balfour has called a “system of mystic and recondite calisthenics”. As we have seen, Lao Tze makes reference to “breathing exercises”, but apparently certain of his followers regarded the performance of these exercises as the sum and substance of his teachings, whereas they were but an aid towards attaining the state of mind which prepared the Taoist for submission to the Tao. Kwang Tze found it necessary to condemn the practices of those “scholars” who, instead of pursuing “the path of self cultivation”, endeavoured to accumulate “the breath of life” so that they might live as long as the [32]patriarch Phăng. In his chapter, “Ingrained Ideas”, he writes:

“Blowing and breathing with open mouth; inhaling and exhaling the breath; expelling the old breath and taking in new; passing their time like the (dormant) bear, and stretching and twisting (the neck) like a bird; all this simply shows the desire for longevity”.52

The genuine devotees “enjoy their ease without resorting to the rivers and seas”, they “attain to longevity without the management (of the breath)”, they “forget all things and yet possess all things by cultivating the qualities of placidity, indifference, silence, quietude, absolute vacancy and non-action”. These qualities “are the substance of the Tao and its characteristics”.53

It seems undoubted, however, that the system of Lao Tze, whereby “spiritual fluid” flowed into the placid, receptive mind, originated in the very practices here condemned—in the quest of “soul substance” contained in water, herbs, metals, and gems. As Indian and Chinese sages retired to solitudes and endured great privations, so that they might accumulate “merit”, so did the searchers for herbs, metals, and gems penetrate desert wastes and cross trackless mountains, so as to accumulate the wealth which was “merit” to them. They were inspired in like manner by genuine religious enthusiasm.

The Taoists never forgot the “Elixir”. Taoism began with the quest of that elusive and mystical “It” which renewed youth and ensured immortality, or prolonged longevity after death, and the later Taoists revived or, perhaps one should say, perpetuated the search for “the Water of Life”, and the “Plant of Life”, the “Peach of 3000 years”, or “10,000 years”, the gem trees, gold, pearls, jade, &c. The fear of death obsessed their minds. They wished to live as long as the Patriarch Phăng on this earth, or to be transferred bodily to the Paradise of the West, the Paradise of Cloudland or Star-land, or that of the “Islands of the Blest”. Besides, it was necessary that the earthly life should be prolonged so that they might make complete submission to the Tao. Their lives had to be passed in tranquillity; they were not to reflect on the past or feel anxiety regarding the future. The fear of death in the future tended to disturb their peace of mind, and they were therefore in need of water which, like the water of Lethe, would make them forget their cares, or some other elixir that would inspire them with confidence and give them strength. Kwang Tze might censure the ascetics for confusing “the means” with “the end”, but ordinary men have always been prone to attach undue importance to ceremonies and rites—to concentrate their thoughts on the performance of rites rather than in accumulating “merit”, and to believe that “merit” can be accumulated by the performance of the rites alone.

The explanation of the state of affairs censured by Kwang Tze seems to be that the transcendental teachings of Lao Tze and himself, in which the vague idea of the Logos was fused with belief in a vague elixir of life, were incomprehensible not only to the masses but even to scholars, and that the practices and beliefs of the older faith on which Lao Tze founded his system were perpetuated by custom and tradition by other adherents to the cult of which he was a teacher. Ordinary men, who were not by temperament or mental constitution or training either mystics or metaphysicians, required something more concrete than the elusive Tao of Lao and Kwang; they clung to their beliefs in the efficacy of life-prolonging herbs, jewels, metals, coloured stones, water, fresh air, &c. Withal, they required something to worship, having always been accustomed to perform religious ceremonies and offer up sacrifices. They could not worship or sacrifice to an abstraction like the Tao. Nor could they grasp the idea of an impersonal God as expressed in the writings of Kwang Tze, who taught:

“God is a principle which exists by virtue of its own intrinsicality, and operates spontaneously without self-manifestation”.

The people clung to their belief in a personal God, or personal gods including dragon-gods, and when the old deities believed in by their ancestors were discredited by their teachers, they deified Lao Tze and his disciples as the Indians deified Buddha and the Rishis. Lao Tze was sacrificed to in the second century B.C., and a superb temple was erected to him. One of the Emperors who embraced the Taoist faith caused the statue of Lao Tze to be carried into his palace, with pomp and ceremony. The ordinary priests in the temples of China were called Taoists.

When Buddhism began to exercise an influence in China between the third century B.C. and the first century A.D., the Taoists borrowed from the Buddhists, while the Buddhists, in turn, borrowed from the Taoists. The myth then arose that when Lao Tze “went west”, he was reborn in India as the Buddha. But the Taoists clung also to the older myth that after Lao Tze died, he ascended to Cloudland and became the personal god of heaven, Shang Ti, the Supreme and Divine Emperor. It was as Shang Ti, a term which includes the spirits of deceased Emperors of China, he was worshipped not only in temples but at domestic shrines, along with the various groups of demi-gods, some of whom were identified with the disciples of Lao Tze. The Chinese Shang Ti, like the ancient Egyptian sun-god Ra and the Babylonian Marduk (Merodach), was the divine father of the living monarch.