CHAPTER XVII

CULTURE MIXING IN JAPAN

Races and Archæological Ages—The “Pit-dwellers”—Ainu Myths and Legends—Mummification—Sacred Animals, Herbs, and Trees—Ainu Cosmogony—Ainu Deluge Legend—Pearl-lore in Japan—Mandrake in Korea, Japan, and China—The Japanese “Dragon-Pearl” as Soul—Links with America—Medicinal Herbs and Jewels—The “God-Body”—Sanctity of Beads—The Coral, Shells, Coins, Fruit, and Feathers of Luck-gods—Jade in Japan—No Jade Necklaces in China—Japanese Imperial Insignia the Mirror, Sword, and Jewel—Shinto Temples and Artemis Gateways—Mikado as Osiris—The Shinto Faith—Yomi—Food of the Dead—The Souls of Mikados and Pharaohs—The Kami as Gods, &c.—Gods of the Cardinal Points.

There was not only “culture” mixing but also a mixing of races in ancient times throughout the Japanese Archipelago. Distinct racial types can be detected in the present-day population. “Of these,” says the Japanese writer, Yei Ozaki,1 “the two known as the patrician and the plebeian are the most conspicuous. The delicate oval face of the aristocrat or Mongoloid, with its aquiline nose, oblique eyes, high-arched eyebrows, bud-like mouth, cream-coloured skin, and slender frame, has been the favourite theme of artists for a thousand years, and is still the ideal of beauty to-day. The Japanese plebeian has the Malayan cast of countenance, high cheek-bones, large prognathic mouth, full, straight eyes, a skin almost as dark as bronze, and a robust, heavily-boned physique. The flat-faced, heavy-jawed, hirsute Ainu type, with luxuriant hair and long beards, is also frequently met with among the Japanese. Such are the diverse elements which go to comprise the race of the present time.”

The oblique-eyed aristocrats—the Normans of Japan—appear to have come from Korea, and to have achieved political ascendancy as a result of conquest in the archæological “Iron Age”, when megalithic tombs of the corridor type, covered with mounds, were introduced.2 They brought with them, in addition to distinctive burial customs, a heritage of Korean religious beliefs and myths regarding serpent- or dragon-gods of rivers and ocean, air and mountains. After coming into contact with other peoples in Japan, their mythology grew more complex, and assumed a local aspect. Chinese and Buddhist elements were subsequently added.

There was no distinct “Bronze Age” in Japan. “Ancient bronze objects are,” says Laufer, “so scarce in Japan, that even granted they were indigenous, the establishment of a Bronze Age would not be justified, nor is there in the ancient records any positive evidence of the use of bronze.”3 Although stone implements have been found, it is uncertain whether there ever was, in the strict Western European sense, a “Neolithic Age”. The earliest inhabitants of the islands could not have reached them until after ships came into use in the Far East, and therefore after the culture of those who used metals had made its influence felt over wide areas.

As we have seen (Chapter III), the most archaic ships in the Kamschatka area in the north, and in the Malayan area in the south, were of Egyptian type, having apparently been introduced by the early prospectors who searched for pearls and precious stones and metals. In the oldest Japanese writings, the records of ancient oral traditions, gold and silver are referred to as “yellow” and “white” metals existing in Korea, while bronze, when first mentioned, is called the “Chinese metal” and the “Korean metal”.4 “The bronze and iron objects found in the ancient graves have simply,” says Laufer, “been imported from the mainland, and plainly are, in the majority of cases, of Chinese manufacture. Many of these, like metal mirrors, certain helmets, and others, have been recognized as such; but through comparison with corresponding Chinese material, the same can be proved for the rest.”5 At the beginning of our era, the Japanese, as the annals of the Later Han Dynasty of China record, purchased iron in Korea. The Chinese and Koreans derived the knowledge of how to work iron from the interior of Siberia, the Turkish Yakut there being the older and better iron-workers.6

The racial fusion in ancient Japan was not complete. Although the Koreans, Chinese, and Malayans intermarried and became “Japanese”, communities of the Ainu never suffered loss of identity, and lived apart from the conquerors and those of their kinsmen who were absorbed by them.

An outstanding feature of Japanese archæology is that Culture A appears to have been a higher one than Culture B, which is represented by Ainu artifacts. Culture A is that of a pre-Ainu people whom the Ainu found inhabiting parts of the archipelago, and called the Koro-pok-guru. The name signifies “the people having depressions”, and is usually rendered by Western writers as “Pit-dwellers”. In the Japanese writings the Koro-pok-guru are referred to as “the small people” and “earth spiders”.

During the winter season the Koro-pok-guru lived in pit-houses, with conical or beehive roofs. The depth of these earth houses was greater on slopes and exposed heights than on low-lying ground. In summer they occupied beehive houses erected on the level. Their “kitchen-midden” deposits have yielded pottery, including well-shaped vases, and arrowheads of flint, obsidian, reddish jasper or dark siliceous rock. Like the “pit-dwellers” of Saghalin and Kamschatka, the Koro-pok-guru were seafarers and fishers. Their houses were erected on river banks and along the sea coast.

Culture B deposits are devoid of pottery. The Ainu have never been potters; their bowls and spoons were in ancient times made of wood. They claim to have exterminated the Koro-pok-guru, who appear to have had affinities with the present inhabitants of the northern Kuriles, a people of short stature, with roundish heads, the men having short, thick beards, and being quite different in general appearance from the “hairy Ainu” with long, flowing beards. Some communities of Ainu present physical characteristics that suggest the blending in ancient times of the “long beards” and “short beards”. The pure Ainu are the hairiest people in the world. They are broad-headed and have brown eyes and black beards, and are of sturdy build. Their tibia and humerus bones are somewhat flat. In old age some resemble the inhabitants of Great Russia.

The Ainu7 are hunters and fishers. Their women cultivate millet (their staple food) and vegetables, and gather herbs and roots among the mountains. According to their own traditions, they came from Sara, which means a “plain”. Their “culture hero”, Okikurumi, descended from heaven to a mountain in Piratoru,8 having been delegated by the Creator to teach the Ainu religion and law. Before this hero returned to heaven, he married Turesh Machi,9 and he left his son, Waruinekuru, to instruct the Ainu “how to make cloth, to hunt and fish, how to make poison and set the spring-bow in the trail of animals”.

When Okikurumi first arrived among the Ainu, the crust of the earth was still thin and “all was burning beneath”. It was impossible for people to go a-hunting without scorching their feet. The celestial hero arranged that his wife should distribute food, but made it a condition that no human being would dare to look in her face. She went daily from house to house thrusting in the food with her great hands.

An inquisitive Ainu, of the “Peeping Tom” order, resolved to satisfy his curiosity regarding the mysterious food-distributor. One morning he seized her and pulled her into his house, whereupon she was immediately transformed into a wriggling serpent-dragon. A terrible thunderstorm immediately broke out, and the house of “Peeping Tom” was destroyed by lightning.

This is an interesting Far Eastern version of the Godiva legend10 of Coventry.

Greatly angered by the breaking of the taboo, Okikurumi returned to the celestial regions. His dragon-wife is not only a Godiva, but another Far Eastern Melusina.11

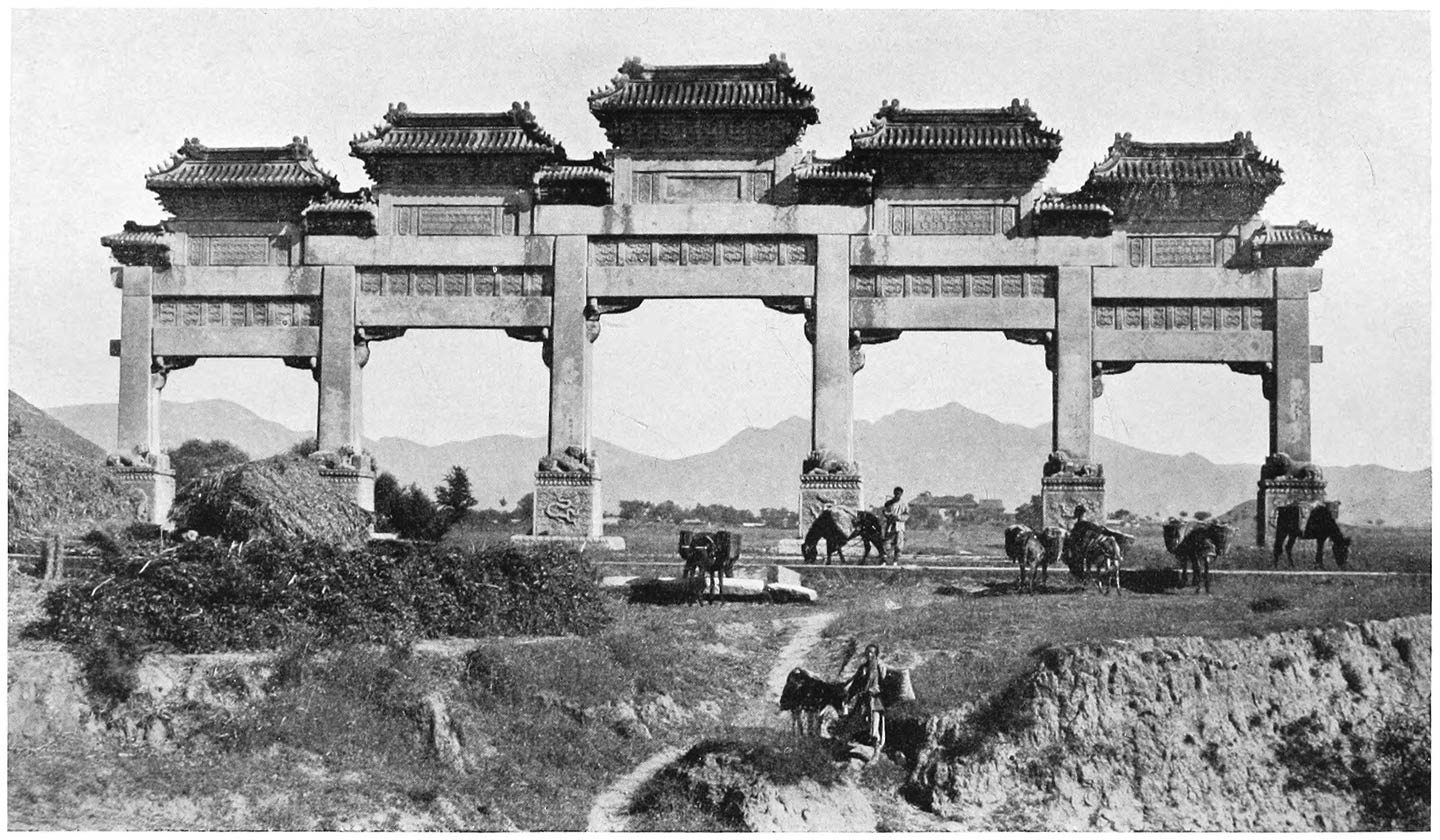

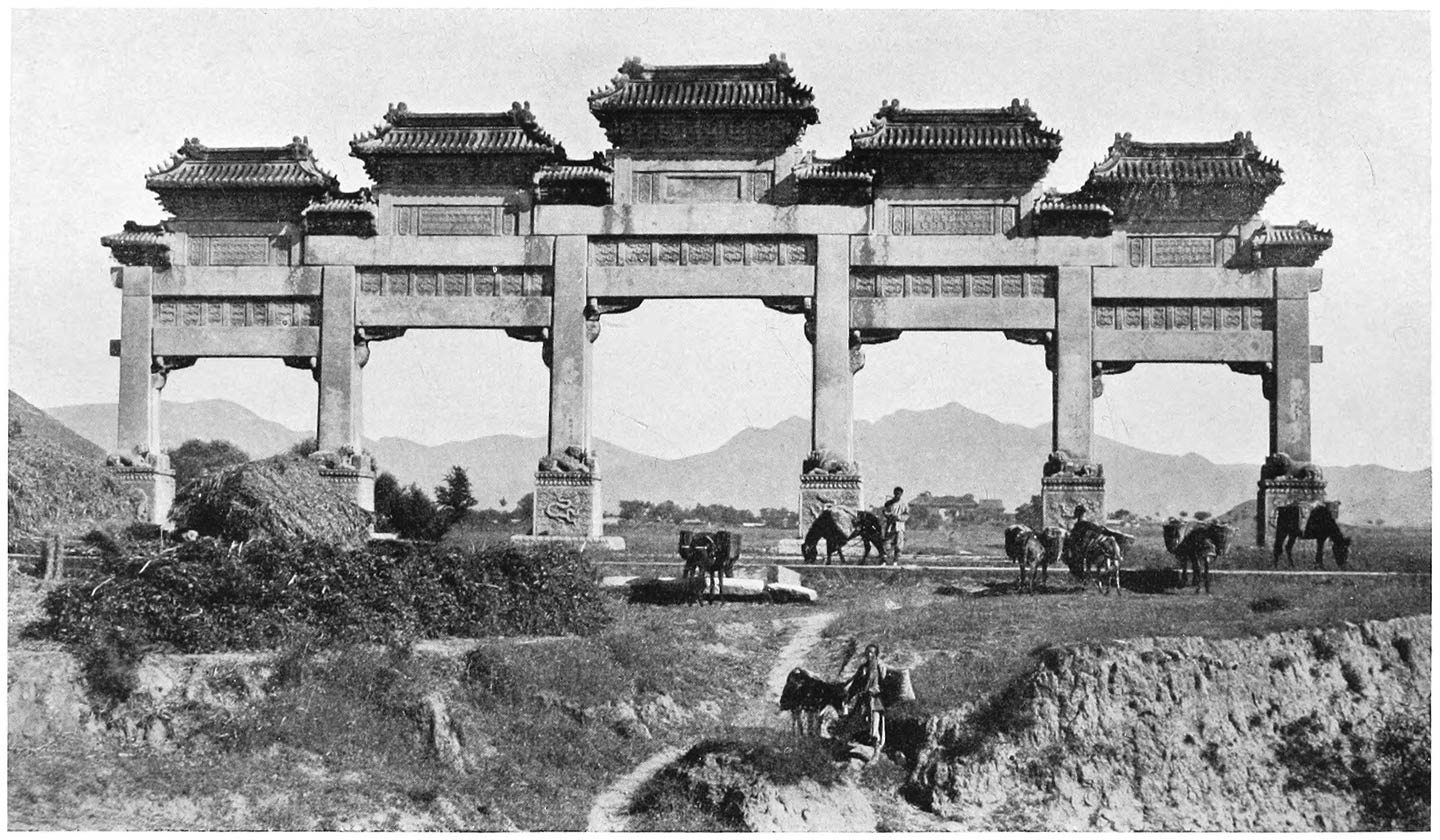

Copyright H. G. Ponting. F.R.G.S.

THE MOST FAMOUS PAI-LO (GODDESS SYMBOL) IN CHINA: AT THE MENG TOMBS, NEAR PEKING

Okikurumi is said to have worn ear-rings. He had therefore a solar connection. The Aryo-Indian hero, Karna, son of Surya, the sun-god, who emerged from an ear of his human mother, Princess Pritha, was similarly adorned at birth with ear-rings. The Ainu have from the earliest times considered it essential that they should all wear ear-rings, and the ears of males and females are bored in childhood. It was similarly a ceremonial practice in ancient Peru to bore the ears of Inca princes. Jacob objected to his wives wearing ear-rings, and buried those so-called “ornaments” with the gods of Laban under an oak at Shechem.12 Bracelets and “ear-ornaments” were similarly favoured as religious charms and symbols by the Ainu.

It is of special interest to note that mummification was practised by some Ainu tribes or families. Whether or not they acquired this custom from the Koro-pok-guru is uncertain. Women tattooed their arms, their upper and lower lips, and sometimes their foreheads. Tattooing and mummification similarly obtained among the Aleutian Islanders. The same peculiar methods of preserving corpses obtained among the Ainu, the Aleutians, and certain Red Indian tribes of North America.13 Another link between the Old and New Worlds is afforded by American-Asiatic bone plate armour.14

Like the Ostiaks and other Siberian tribes, the Ainu worship the bear. Their bear feasts are occasions for heavy drinking and much dancing and singing. Drunkenness is to them “supreme bliss”.

The bear-goddess was the wife of the dragon-god. She had a human lover, and that is why bears, her descendants, “are half like a human being”. [3

The salmon is divine, and its symbol is worshipped. Folk-tales are told regarding salmon taking human shape, as do the seals in Scottish Gaelic stories. As in China and Japan, the fox is the most subtle of all beasts. It supplanted the tiger as chief god, according to an Ainu folk-tale. There is a great tortoise-god in the sea and an owl-god on the land, and their children have intermarried. The cock is of celestial origin. It was, at the beginning, sent down from heaven by the Creator to ascertain what the world looked like, but tarried for so long a time, being well pleased with things, that it was forbidden to return. Hares are mountain deities.

The oldest trees are the oak and pine, and they are therefore sacred, and the oldest and most sacred herb is the mugwort. In Kamschatka the pine is associated with the mugwort. The mugwort is connected with goddesses of the Artemis order.15 Sacred, too, was the willow, and specially sacred the mistletoe that grew on a willow tree. An elixir prepared from the mistletoe was supposed to renew youth, and therefore to prolong life and cure diseases. Siberians venerate the herb willow.16 The drink prepared from it was a soporific for human beings, wild animals, and deities. Far Eastern deities had apparently to be soothed as well as invoked as, it may be recalled, was Hathor-Sekhet in the Egyptian “flood myth”, when she was given beer poured out from jars, so that she might cease from slaughtering mankind.17

When the Ainu performed religious ceremonies, shavings and whittled sticks of willow were used, and libations of intoxicating liquors provided. Deities were made drunk, as in Babylonia,18 and then provided with a [3 soothing anti-intoxicant. The Ainu set up their willow sticks at wells and around their dwellings. They had no temples, and when they worshipped the sun, a shaven willow stick was placed at the east end of a house.

The moon-god came next in order to the sun-god. The fire-god was invoked to cure disease. There was a subtle connection between fire and mistletoe, perhaps because fire was obtained by friction of soft and hard wood, and an intoxicating elixir prepared from a tree or its parasite was believed to be “fire water”—that is, “water of life”. Offerings were made to gods of ocean, rivers, and mountains.

The world was supposed to be floating on and surrounded by water, and to be resting on the spine of a gigantic fish which caused earthquakes when it moved. There were two heavens—one above the clouds and another in the Underworld. A hell, from which the volcanoes vomit fire, was reserved for the wicked.

Like the Chinese, the Ainu tell stories of visits paid to Paradise. A man, whose wife had been spirited away, appealed to the oak-god, who provided him with a golden horse on which he rode to the sky. He reached a beautiful city in which people went about singing constantly. They smelled a stranger, and, the smell being offensive to them, they appealed to the chief god to give him his wife. The god promised to do so if the visitor would agree to go away at once. He consented readily, and returned to the oak-god, who told him his wife was in hell, and that the place was now in confusion because the chief god had ordered a search to be made for her. Soon afterwards the lost woman was restored to her husband. This man was given the golden horse to keep, and all the horses in Ainu-land are descended from it.

Another man once chased a bear on a mountain side. [3 The animal entered a cave, and he followed it, passing through a long, dark tunnel. He reached the beautiful land of the Underworld. Feeling hungry, he ate grapes and mulberries, and, to his horror, was immediately transformed into a serpent. He crawled back to the entrance and fell asleep below a pine tree. In his dream the goddess of the tree appeared. She told him he had been transformed into a serpent because he had eaten of the food of Hades, and that, if he wished to be restored to human shape, he must climb to the top of the tree and fling himself down. When he awoke, the man-serpent did as the goddess advised. After leaping from the tree top, he found himself standing below it, while near him lay the body of a great serpent which had been split open. He then went through the tunnel and emerged from the cave. But later he had another dream, in which the goddess appeared and told him he must return to the Underworld because a goddess there had fallen in love with him. He did as he was commanded to do, and was never again seen on earth.

A story tells of another Ainu who reached this Paradise. He saw many people he had known in the world, but they were unable to see him. Only the dogs perceived him, and they growled and barked. Catching sight of his father and mother he went forward to embrace them, but they complained of being haunted by an evil spirit, and he had to leave them.

The Ainu have a Deluge Myth which tells that when the waters rose the vast majority of human beings were destroyed. Only a remnant escaped by ascending to the summit of a high mountain.19

Although the Ainu claimed to have exterminated the Koro-pok-guru, it is possible that they really intermixed with them and derived some of their religious ideas and myths from them, and that, in turn, the Japanese were influenced by both Ainu and Koro-pok-guru ideas and myths. The aniconic pillars and the female goddess with fish termination (the Dragon Mother) figure in Japanese as well as Ainu religion. Both are found in Kamschatka, too. Dr. Rendel Harris, commenting on the pillar and fish-goddess idols of the Kamschatdals,20 recalls “the various fish forms of Greek and Oriental religions, the Dagon and Derceto of the Philistines, the Oannes of the Assyrians,21 Eurynome of the Greek legends, and the like”. The pillar, sometimes shown to be clad with ivy, links with the symbols of Hermes and Dionysos. He adds: “The Kamschatdals and other Siberian tribes manufacture for themselves intoxicating and stupefying drinks which have a religious value, and are employed by their Shamans in order to produce prophetic states of inspiration”. The Japanese manufactured sake from rice with precisely the same motive, and, like the Ainu, offered their liquor to the gods.

What attracted the Koro-pok-guru and the Ainu to Japan? As we have seen (Chapter III), the primary incentive for sea-trafficking and prospecting by sea and land was the desire to obtain wealth in the form of pearls, precious stones, and metals. Now, pearls are found round the Japanese coasts. Marco Polo has recorded that in his day the people of Japan practised the mortuary custom (obtaining also in China) of placing pearls in the mouths of the dead. “In the Island of Zipangu22 (Japan),” he says, “rose-coloured pearls were abundant, and quite as valuable as white ones.” Kaempfer, writing in the eighteenth century, stated that the Japanese pearls were found in small varieties of oysters (akoja) resembling the Persian pearl oyster, and also in “the yellow snail-shell”, the taira gai (Placuna), and the awabi or abalone (Haliotis). A pearl fishery formerly existed in the neighbourhood of Saghalin Island. As pearls have from the earliest times been fished from southern Manchurian rivers, in Kamschatka, and on the south coast of the Sea of Okhotsk, it may be that the earliest settlers in Japan were prehistoric pearl-fishers. It is of special interest to note here that, according to G. A. Cooke, pearls and ginseng (mandrake) were formerly Manchurian articles of commerce.23 The herbs and pearls were, as we have seen, regarded as “avatars” of the mother-goddess.

In Korea ginseng is cultivated under Government supervision. “It is”, Mrs. Bishop writes,24 “one of the most valuable articles which Korea exports, and one great source of its revenue.” A basket may contain ginseng worth £4000. “But,” she adds, “valuable as the cultivated root is, it is nothing to the value of the wild, which grows in Northern Korea, a single specimen of which has been sold for £40! It is chiefly found in the Kang-ge Mountains, but it is rare, and the search so often ends in failure, that the common people credit it with magical properties, and believe that only men of pure lives can find it.” The dæmon who is “the tutelary spirit of ginseng … is greatly honoured” (p. 243). A ready market is found in China for Korean ginseng. “It is a tonic, a febrifuge, a stomachic, the very elixir of life, taken spasmodically or regularly in Chinese wine by most Chinese who can afford it” (p. 95).

In Japan, ginseng, mushroom, and fungus are, like pearls, promoters of longevity, and sometimes, says Joly, “masquerade as phalli”: they are “Plants of Life” and “Plants of Birth”, like the plants searched for by the Babylonian heroes Gilgamesh and Etana, and like the dragon-herbs of China.25

In Shinto, the ancient religion of the Japanese, prominence is given to pearls and other precious jewels, and even to ornaments like artificial beads, which were not, of course, used merely for personal decoration in the modern sense of the term; beads had a religious significance. A sacred jewel is a tama, a name which has deep significance in Japan, because mi-tama is a soul, or spirit, or double. Mi is usually referred to as an “honorific prefix” or “honorific epithet”, but it appears to have been originally something more than that. A Japanese commentator, as De Visser notes, has pointed out in another connection26 that mi is “an old word for snake”, that is, for a snake-dragon. Mi-tama, therefore, may as “soul” or “double” be all that is meant by “snake-pearl” or “dragon-pearl”.27 The pearl, as we have seen, contained “soul substance”, the “vital principle”, the blood of the Great Mother, like the “jasper of Isis” worn by women to promote birth, and therefore to multiply and prolong life; in China and Japan the pearl was placed in the mouth of the dead to preserve the corpse from decay and ensure longevity or immortality. The connection between jewels and medicine is found among the Maya of Central America. Cit Bolon Tun (the “nine precious stones”) was a god of medicine. The goddess Ix Tub Tun (“she who spits out precious stones”) was “the goddess of the workers in jade and amethysts”. She links with Tlaloc’s wife.

According to Dr. W. G. Aston28 tama contains the root of the verb tabu, “to give”, more often met with in its lengthened form tamafu. “Tama retains its original significance in tama-mono, a gift thing, and toshi-dama, a new year’s present. Tama next means something valuable, as a jewel. Then, as jewels are mostly globular in shape,29 it has come to mean anything round. At the same time, owing to its precious quality, it is used symbolically for the sacred emanation from God which dwells in his shrine, and also for that most precious thing, the human life or soul.… The element tama enters into the names of several deities. The food-goddess is called either Ukemochi no Kami or Uka no mi-tama.” Phallic deities are also referred to as mi-tama. The mi-tama is sometimes used in much the same sense as the Egyptian Ka: it is the spirit or double of a deity which dwells in a shrine, where it is provided with a shintai (“god body”)—a jewel, weapon, stone, mirror, pillow, or some such object.

The jewels (tama) worn by gods and human beings were not, as already insisted upon, merely ornaments, but objects possessing “soul substance”. These are referred to in the oldest Shinto books. In ancient Japanese graves archæologists have found round beads (tama), “oblong perforated cylinders” or “tube-shaped beads” (kuda-tama), and “curved” or “comma-shaped30 beads” (maga-tama). According to W. Gowland, “the stones of which maga-tama are made are rock-crystal, steatite, jasper, agate, and chalcedony, and more rarely chrysoprase and nephrite (jade)”. He notes that “the last two minerals are not found in Japan”.31

Henri L. Joly, writing on the tama, says32 it is also “represented in the form of a pearl tapering to a pointed apex, and scored with several rings. It receives amongst other names Nio-i-Hojiu, and more rarely of Shinshi, the latter word being used for the spherical jewel, one of the three relics left to Ninigi no Mikoto33 by his grandmother, Amaterâsu.34 The necklace of Shinshi, mentioned in the traditions, was lost, and in its place a large crystal ball, some three or four inches in diameter, is kept and carried by an aide-de-camp of the Emperor on State occasions.”

The pearl (tama) is “one of the treasures of the Takaramono, a collection of objects associated with the Japanese gods of luck, which includes the hat of invisibility (Kakuregasa), a lion playing with a jewel, a jar containing coral, coins, &c.; coral branches (sangoju), the cowrie shell (kai), an orange-like fruit, the five-coloured feather robe of the Tennins, the winged maidens of the Buddhist paradise, copper cash, &c.”35 But although the tama may correspond to the mani of the Indian Buddhists, it was not of Buddhist origin in Japan; the Buddhists simply added to the stock of Japanese “luck jewels”.

The tama of jade has raised an interesting problem. Nephrite is not found in Japan. “It is difficult”, says Laufer, “to decide from what source, how and when the nephrite or jadeite material was transmitted to Japan.” Referring to jade objects found in the prehistoric Japanese graves, he says: “The jewels may go back, after all, to an early period when historical intercourse between Japan and China was not yet established; they36 represent two clearly distinct and characteristic types, such as are not found in the jewelry of ancient China. If the Japanese maga-tama and kuda-tama would correspond to any known Chinese forms, it would be possible to give a plausible reason for the presence of jade in the ancient Japanese tombs; but such a coincidence of type cannot be brought forward. Nor is it likely that similar pieces will be discovered in China, as necklaces were never used there anciently or in modern times. We must therefore argue that the two Japanese forms of ornamental stones were either indigenous inventions or borrowed from some other non-Chinese culture sphere in south-eastern Asia, the antiquities of which are unknown to us.”37

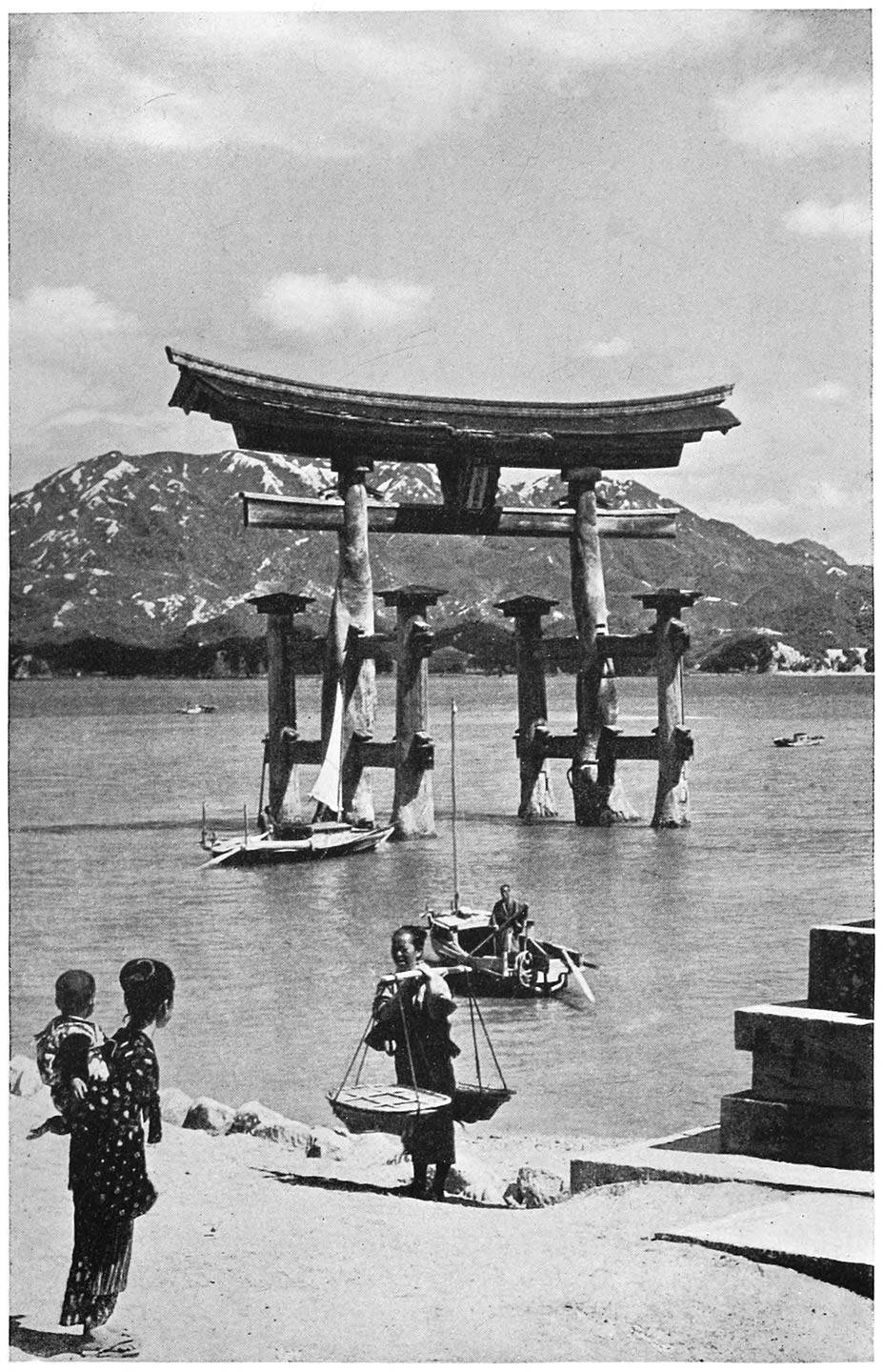

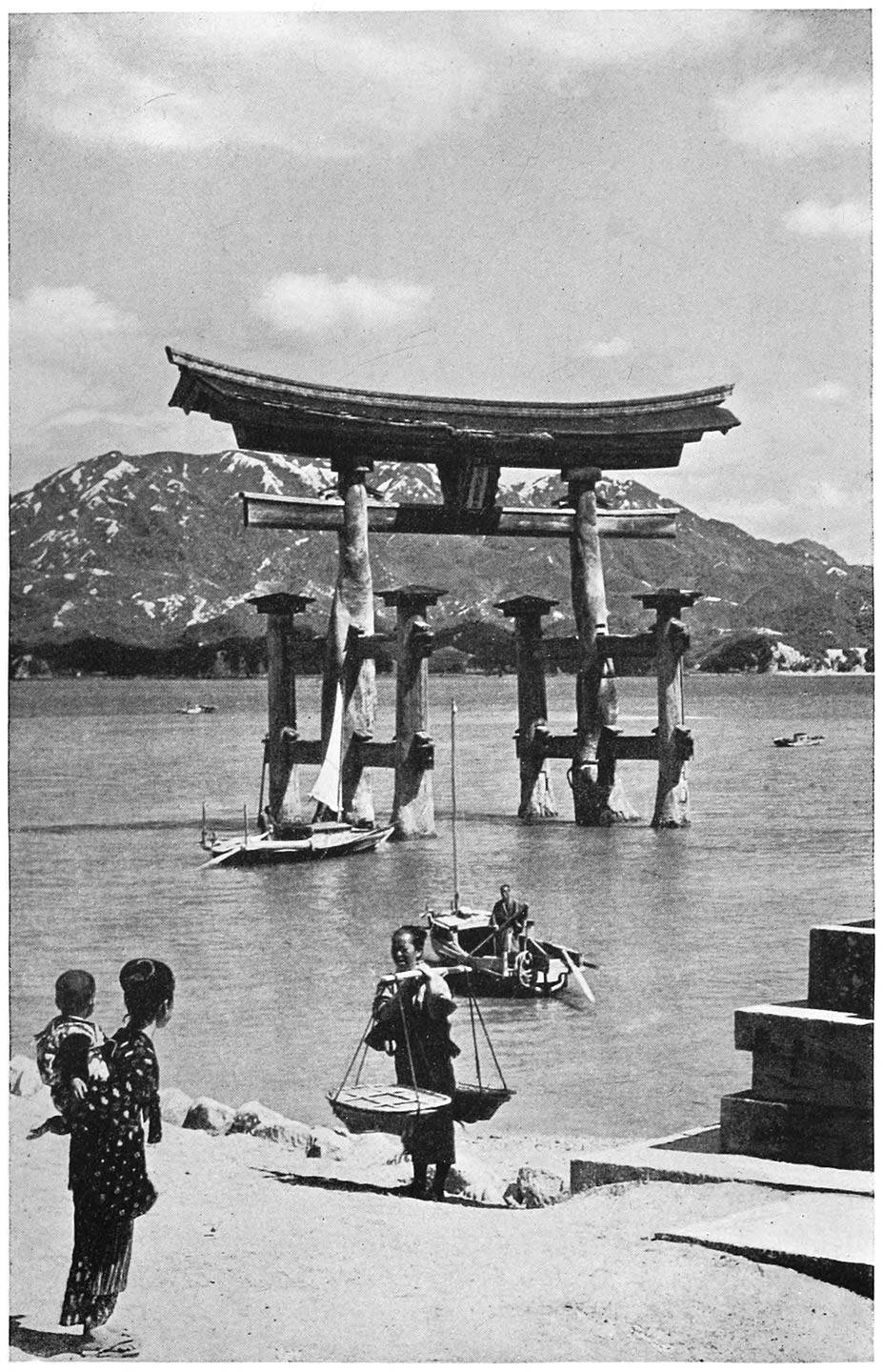

Copyright H. G. Ponting. F.R.G.S.

THE FAMOUS OLD TORI-WI (GODDESS SYMBOL), MIYAJIMA, JAPAN

Miyajima or Itskushima (“Island of Light”) is one of the San-Kei or “Three most beautiful scenes of Japan”. The island is sacred to Benten, the Goddess of the Sea, of Beauty, of Wealth—one of the seven Divinities of Luck (see “The Japanese Treasure Ship”,).

The tama is of great importance in Shinto religion. At Ise,38 “the Japanese Mecca”, which has long been visited by pious pilgrims, a virgin daughter of the Mikado used to keep watch over the three imperial insignia—the mirror, the sword, and the jewel (tama)—which had been handed down from Mikado to Mikado. There were no idols in the temples. The Shintai was carefully wrapped up and kept in a box in the “holy of holies”, a screened-off part of the simple and unadorned wooden and thatched little temple. The temple was entered through a gateway—the tori wi, a word which means “bird-perch”, in the sense of a hen-roost. “As an honorary gateway”, says Dr. Aston, “the tori-wi is a continental institution identical in purpose and resembling in form the toran of India, the pailoo of China, and the hong-sal-mun of Korea.”39 When this symbol of Artemis40 was introduced into Japan is uncertain. “Rock gates” were of great sanctity in old Japan. There is one at Ise—the “twin-rocks of Ise”.

The mirror was the shintai (god-body) of the sun-goddess; the sword was the shintai of the dragon; and the jewel (tama) was the shintai of the Great Mother, who was the inexhaustible womb of nature. At sacred Ise, the chief deities worshipped were Ama-terâsu, the goddess of the sun, and Toyouke-hime, the goddess of food.41 The high-priest was the Mikado, who was a Kami (a god), and called “the Heavenly Grandchild”, his heir being “august child of the sun”, and his residence “the august house of the sun”.42 After the Mikado had ascended the throne, the Ohonihe (great food offering) ceremony was performed. It was “the most solemn and important festival of the Shinto religion”, says Aston, who quotes the following explanation of it by a modern Japanese writer:

“Anciently the Mikado received the auspicious grain from the Gods of Heaven and therewithal nourished the people. In the Daijowe (or Ohonihe) the Mikado, when the grain became ripe, joined unto him the people in sincere veneration, and, as in duty bound, made return to the Gods of Heaven. He thereafter partook of it along with the nation. Thus the people learnt that the [34]grain which they eat is no other than the seed bestowed on them by the Gods of Heaven.”

The Mikado was thus, in a sense, a Japanese Osiris.

Shinto religion was in pre-Buddhist days a system of ceremonies and laws on which the whole social structure rested. The name is a Chinese word meaning “the way of the gods”, the Japanese equivalent being Kami no michi. But although the gods were numerous, only a small proportion of them played an important part in the ritual (norito), which was handed down orally by generations of priests until after the fifth century of our era, when a native script, based on Chinese characters, came into use.

Old Shinto was concerned chiefly with the food-supply, with child-getting, with the preservation of health, and protection against calamities caused by floods, droughts, fire, or earthquakes. It has little or nothing to say regarding the doctrine of immortality. There was no heaven and no hell. The spirits of some of these deities who died like ordinary mortals went to the land of Yomi, as did also the spirit of the Mikado, but little is told regarding the mysterious Otherworld in which dwelt the spirits of disease and death. “In one passage of the Nihon-gi,” says Aston,43 “Yomi is clearly no more than a metaphor for the grave.” It thus resembled the dark Otherworld or Underworld of the Babylonians, from which Gilgamesh summoned the spirit of his dead friend, Ea-bani.44 No spirit of a god could escape from Yomi after eating “the food of the dead”. When the Babylonian god Adapa, son of Ea, was summoned to appear in the Otherworld, his father warned him not to accept of [34]the water and food which would be offered him.45 The goddess Ishtar was struck with disease when she entered Hades in quest of her lover, the god Tammuz, and it was not until she had been sprinkled with the “water of life” that she was healed and liberated.46

The Mikado, being a god, had a spirit, and might be transferred to Yomi or might ascend to heaven to the celestial realm of his ancestress, the sun-goddess. Some distinguished men had spirits likewise. But there is no clear evidence in the Ko-ji-ki or the Nihon-gi that the spirits of the common people went anywhere after death, or indeed, that they were supposed to have spirits. Some might become birds, or badgers, or foxes, and live for a period in these forms, and then die, as did some of the gods. There are no ghosts in the early Shinto books.47

The ancient Pharaohs of Egypt, like the ancient Mikados of Japan, were assured of immortality. The mortuary Pyramid Texts “were all intended for the king’s exclusive use, and as a whole contain beliefs which apply only to the king”. There are vague references in these texts to the dead “whose places are hidden”, and to those who remain in the grave.48 The fate of the masses did not greatly concern the solar cult.

Before dealing with the myths of Japan, it is necessary to consider what the term kami, usually translated “gods”, signified to the devotees of “Old Shinto”. The kami were not spiritual beings, but many of them had spirits or doubles that resided in the shintai (god body). Dr. Aston reminds us that although kami “corresponds in a general way to ‘god’, it has some important limitations. The kami are high, swift, good, rich, living but not [34]infinite, omnipotent, or omniscient. Most of them had a father and mother, and of some the death is recorded.”49 It behoves us to exercise caution in applying the term “animistic” to the numerous kami of Japan, or in assuming that they were worshipped, or reverenced rather, simply because they were feared. Some of the kami were feared, but the fear of the gods is not a particular feature of Shinto religion with its ceremonial hand-clappings and happy laughter.

Dr. Aston quotes from Motöori, the great eighteenth century Shinto theologian, the following illuminating statement regarding the kami:

“The term kami is applied in the first place to the various deities of heaven and earth who are mentioned in the ancient records as well as to their spirits (mi-tama) which reside in the shrines where they were worshipped. Moreover, not only human beings, but birds, beasts, plants, and trees, seas and mountains, and all other things whatsoever which deserve to be dreaded and revered for the extraordinary and pre-eminent powers which they possess are called kami. They need not be eminent for surpassing nobleness, or serviceableness alone. Malignant and uncanny beings are also called kami if only they are objects of general dread. Among kami who are human beings, I need hardly mention, first of all, the successive Mikados—with reverence be it spoken.… Then there have been numerous examples of divine human beings, both in ancient and modern times, who, although not accepted by the nation generally, are treated as gods, each of his several dignity, in a single province, village, or family.”

In ancient Egypt the reigning monarch was similarly a god—a Horus while he lived and an Osiris after he died, while a great scholar like Imhotep (the Imuthes of the Greeks in Egypt who identified him with Asklepois) might be deified and regarded as the son of Ptah, the god [34]of Memphis. Egypt, too, had its local gods like Japan; so had Babylonia.

The Japanese theologian proceeds to say:

“Amongst kami who are not human beings, I need hardly mention Thunder (in Japanese Nuru kami or the sounding-god). There are also the Dragon and Echo (called in Japanese Ko-dama or the Tree Spirit), and the Fox, who are kami by reason of their uncanny and fearful natures. The term kami is applied in the Nihon-gi and Manjoshiu to the tiger and the wolf. Isanagi (the creator-god) gave to the fruit of the peach and to the jewels round his neck names which implied that they were kami.”50

Here we touch on beliefs similar to those that obtained in China where the dragon and tiger figure so prominently as the gods of the East and the West. The idea that the peach was a kami appears to be connected with the Chinese conception of a peach world-tree, a form of the Mother Goddess, the fruit of which contains her “life substance” or shen as do the jewels like the pearl and jade objects; the peach is a goddess symbol as the phallus is a symbol of a god.

Motöori adds:

“There are many cases of seas and mountains being called kami. It is not their spirits which are meant. The word was applied directly to the seas or mountains themselves as being very awful things.”51

There were a beneficent class and an evil class of kami. Beneficent deities provided what mankind required or sought for; they were protectors and preservers. Four guardians of the world were called “Shi Tenno”. They were posted at the cardinal points like the Chinese Black Tortoise (north), the Red Bird (south), the White Tiger (west), and the Blue or Green Dragon (east). The Japanese colour scheme, however, is not the same as the Chinese. At the north is the blue god Bishamon or Tamoten; at the south the white-faced warrior Zocho; at the west the red-faced Komoku with book and brush or a spear; and at the east the warrior with green face, named Jikoku, who is sometimes shown trampling a demon under foot.

In India the north is white and the south black, and in Ceylon the Buddhist colours of the cardinal points are yellow (north), blue (south), red (west), and white (east).

Although it is customary to regard the coloured guardians of the Japanese world as of Buddhist origin, it may well be that the original Japanese guardians were substituted by the Hindu and Chinese divinities imported by the Buddhists. The dragon-gods of China and Japan were pre-Buddhistic, as De Visser has shown,52 but were given, in addition to their original attributes, those of the naga (serpent or dragon) gods introduced by Buddhist priests.