CHAPTER XVIII

JAPANESE GODS AND DRAGONS

Japanese Version of Egyptian Flood Myth—A Far Eastern Merodach—Dragon-slaying Story—The River of Blood—Osiris as a Slain Dragon—Ancient Shinto Books—Shinto Cosmogony—Separation of Heaven and Earth—The Cosmic “Reed Shoot” and the Nig-gil-ma—The Celestial Jewel Spear—Izanagi and Izanami—Births of Deities and Islands—The Dragons of Japan—The Wani—Bear, Horse, and other Dragons—Horse-sacrifice in Japan—Buddhist Elements in Japanese Dragon Lore—Indian Nagas—Chinese Dragons and Japanese Water-Snakes.

There is no Shinto myth regarding the creation of man; the Mikados and the chiefs of tribes were descendants of deities. Nor is there a Deluge Myth like the Ainu one, involving the destruction of all but a remnant of mankind. The Chinese story about Nu Kwa, known to the Japanese as Jokwa, was apparently imported with the beliefs associated with the jade which that mythical queen or goddess was supposed to have created after she had caused the flood to retreat, but it does not find a place in the ancient Shinto books. There is, however, an interesting version of the Egyptian flood story which has been fused with the Babylonian Tiamat dragon-slaying myth. Susa-no-wo,1 a Far Eastern Marduk, slays an eight-headed dragon and splits up its body, from which he takes a spirit-sword—an avatar of the monster.

Hathor-Sekhet, of the Egyptian myth, was made drunk, so that she might cease from slaying mankind, and a flood of blood-red beer was poured from jars for that purpose. Susa-no-wo provides sake (rice beer) to intoxicate the dragon which has been coming regularly—apparently once a year—for a daughter of an earth god. When he slays it, the River Hi is “changed into a river of blood”.

Another version of the Egyptian myth, as the Pyramid Texts bear evidence, appears to refer to the “Red Nile” of the inundation season as the blood of Osiris, who had been felled by Set at Nedyt, near Abydos.2 Lucian tells that the blood of Adonis was similarly believed to redden each year the flooded River of Adonis, flowing from Lebanon, and that “it dyed the sea to a large space red”.3 Here Adonis is the Osiris of the Byblians. Osiris, as we have seen, had a dragon form; he was the dragon of the Nile flood, and the world-surrounding dragon of ocean.4 He was also the earth-giant; tree and grain grew from his body.5 The body of the eight-headed Japanese dragon was covered with moss and trees.

Susa-no-wo, as the rescuer of the doomed maiden, links with Perseus, the rescuer of Andromeda from the water-dragon.6 The custom of sacrificing a maiden to the Nile each year obtained in Ancient Egypt. In the Tiamat form of the Babylonian myth, Marduk cut the channels of the dragon’s blood and “made the north wind bear it away into secret places”.7 The stories of Pʼan Ku of China and the Scandinavian Ymir, each of whose blood is the sea, are interesting variants of the legend.8

The Japanese dragon-flood myth is merely an incident in the career of a hero in Shinto mythology, which is a mosaic of local or localized and imported stories, somewhat clumsily arranged in the form of a connected narrative.

Our chief sources of information regarding these ancient Japanese myths are the Shinto works, the Ko-ji-ki and the Nihon-gi.9 Of these works, the Ko-ji-ki (“Records of Ancient Matters”) is the oldest; it was completed in Japanese in A.D. 712; the Nihon-gi (“Chronicles of Japan”) was completed in A.D. 720 in the Chinese language.

Although the myths, formerly handed down orally by generations of priests, were not collected and systematized until about 200 years after Buddhism was introduced into Japan, they were not greatly influenced by Indian ideas. Dragon-lore, however, became so complex that it is difficult to sift the local from the imported elements.

In the preface to the Ko-ji-ki, Yasumaro, the compiler, in his summary, writes:

“Now when chaos had begun to condense, but force and form were not yet manifest, and there was nought named, nought done, who could know its shape? Nevertheless Heaven and Earth first parted, and the Three Deities performed the commencement of Creation; the Passive and Active Essences then developed, and the Two Spirits became the Ancestors of all things.”

The myth of the separation of Heaven and Earth dates back to remote antiquity in Egypt. Shu, the atmosphere-god, separated the sky-goddess Nut from the earth-god Seb. In Polynesian mythology Rangi (Heaven), and Papa (Earth), from whom “all things originated”, were “rent apart” by Tane-mahuta, “the god and father of forests, of birds, of insects”. But in this case the earth is the mother and the sky the father.10

About the “Three Deities” referred to by Yasumaro, we do not learn much. The idea of the trinity may have been of Indian origin. The Passive and Active Essences recall the male Yang and its female Yin principles of China. These are represented in the Ko-ji-ki by Izanagi (“Male who Invites”) and Izanami (“Female who Invites”).

Dr. Aston translates the opening passage of the Nihon-gi as follows:

“Of old, Heaven and Earth were not yet separated, and the In and the Yo not yet divided. They formed a chaotic mass like an egg, which was of obscurely defined limits, and contained germs. The purer and clearer part was thinly diffused and formed Heaven, while the heavier and grosser element settled down and became Earth. The finer element easily became a united body, but the consolidation of the heavy and gross element was accomplished with difficulty. Heaven was therefore formed first, and Earth established subsequently. Thereafter divine beings were produced between them.”

Here we meet with the cosmic egg, from which emerged the Chinese Pʼan Ku, the Indian Brahma, the Egyptian Ra or Horus, and one of the Polynesian creators. It might be held that China is the source of the Japanese myth, because the In and the Yo are here, quite evidently the Yang and the Yin, representing not Izanagi and Izanami as in the Ko-ji-ki, but the deities of heaven and earth. But the Ko-ji-ki form of the myth may be the oldest, and we may have in the Nihon-gi evidence of Chinese ideas having been superimposed on those already obtaining in Japan, into which they were imported from other areas.

But to return to the Creation myth. An ancient native work, the Kiu-ji-ki, which has not yet been translated into English, refers to seven generations of gods, beginning with one of doubtful sex, in whose untranslatable name the sun, moon, earth, and moisture are mentioned. This First Parent of the deities was the offspring of Heaven and Earth. The last couple is Izanagi and Izanami, brother and sister, like Osiris and Isis, who became man and wife.

According to the Ko-ji-ki the first three deities came into being in Takama-no-hara, the “Plain of High Heaven”. They were alone, and afterwards disappeared, i.e. died. The narrative continues: “The names of the deities that were born next from a thing that sprouted up like unto a reed-shoot when the earth, young and like unto floating oil, drifted about medusa-like,11 were the Pleasant-Reed-Shoot-Prince-Elder-Deity, next the Heavenly-Eternally-Standing-Deity. These two Deities were likewise born alone, and hid their persons.”12 Earth and mud deities followed, and also the other deities who were before Izanagi and Izanami.

It may be that the “reed-shoot” was the Japanese nig-gil-ma. (See Chapter XIII.) As in one of the early [35]Sumerian texts, the mysterious plant, impregnated with preserving and perpetuating “life substance”, was the second product of Creation.

Izanagi and Izanami were told by the elder deities that they must “make, consolidate, and give birth to this drifting land”. They were then given the Ame no tama-boko, the “Celestial Jewel-spear”. It is suggested that the spear is a phallic symbol. The jewel (tama) is “life substance”. Izanagi and Izanami stood on “the floating bridge of heaven”, which Aston identifies with the rainbow, or, as some Japanese scholars put it, the “Heavenly Rock Boat”, or “Heavenly Stairs”, and pushed down the tama-boko and groped with it until they found the ocean. According to the Ko-ji-ki, they “stirred the brine until it went curdle-curdle (koworo-koworo)”, that is, as Chamberlain suggests, “thick and glutinous”. Others think the passage should be translated so as to indicate that the brine gave forth “a curdling sound”. When the primæval waters and the oily mud began to “curdle” or “cook”, the deities drew up the spear. Some of the cosmic “porridge” dropped from the point and formed an island, which was named Onogoro (“self-curdling”, or “self-condensed”). The deities descended from heaven and erected on the island an eight-fathom house13 with a central pillar. Here we meet with the aniconic pillar, the “herm” of Kamschatkan religion, the pillar of the Vedic world-house erected by the Aryo-Indian god Indra, the “branstock” of Scandinavian religion, the pillar of the “Lion Gate” of Mycenæ; the “pillar” is the “world spine”, like the Indian Mount Meru.14 “The central pillar of a house (corresponding to our king-post) is,” writes Dr. Aston, “at the present day, an object of [35]honour in Japan as in many other countries. In the case of Shinto shrines, it is called Nakago no mibashira (‘central august pillar’), and in ordinary houses the Daikoku-bashira.”15

Izanagi and Izanami become man and wife by performing the ceremony of going round the pillar and meeting one another face to face. Their first-born is Hiruko (leech-child). At the age of three he was still unable to stand upright, and was in consequence placed in a reed boat and set adrift on the ocean.

Here we have what appears to be a version of the Moses story. The Indian Karna, who is similarly set adrift, was a son of Surya, god of the sun. The Egyptian Horus was concealed after birth on a floating island, and he was originally a solar deity with a star form.16 Ra, the Egyptian sun-god, drifted across the heavens on reed floats before he was given a boat. Osiris was, after death, set adrift in a chest. When the Egyptians paid more attention to the constellations than they did in the early period of their history, they placed in the constellation of Argo the god Osiris in a chest or boat. In the Greek period Canopus, the chief star of the constellation of Argo, is the child Horus in his boat. Horus was a reincarnation of Osiris. The Babylonian Ea originally came to Eridu in a boat, which became transformed into a fish-man. As the sign for a god was a star, Ea was apparently supposed to have come from one. Lockyer refers to Egyptian and Babylonian temples, which were “oriented to Canopus”.17 Sun-gods were the offspring of the mother-star, or their own souls were stars by night. “Hiruko,” says Aston, “is in reality simply a masculine [35]form of Hirume, the sun female.”18 The sun and moon had not, however, come into existence when he was set adrift, and it may be that as the “leech-child” he was a star. He became identified in time with Ebisu (or Yebisu), god of fishermen, and one of the gods of luck.

Izanagi and Izanami had subsequently as children the eight islands of Japan, and although other islands came into existence later, Japan was called “Land-of-the-Eight-great-Islands” (Oho-ya-shima-kuni). “When,” continues the Ko-ji-ki, “they (Izanagi and Izanami) had finished giving birth to countries they began afresh, giving birth to deities (kami).” These included “Heavenly-Blowing Male”, “Youth of the Wind”, the sea-kami, “Great-Ocean-Possessor”, “Foam Calm”, “Foam Waves”, “Heavenly-Water-Divider”, or “Water-Distributor” (Ame-no-mi-kumari-no-kami), and the deities of mountains, passes, and valleys.

According to the Nihon-gi, the gods of the sea to whom Izanagi and Izanami gave birth are called Watatsumi, which means “sea children”, or, as Florenz translates it, “Lords of the Sea”. Wata, so like our “water”, is “an old word for sea”. It is probable that, as De Visser says, “the old Japanese sea-gods were snakes or dragons”.19

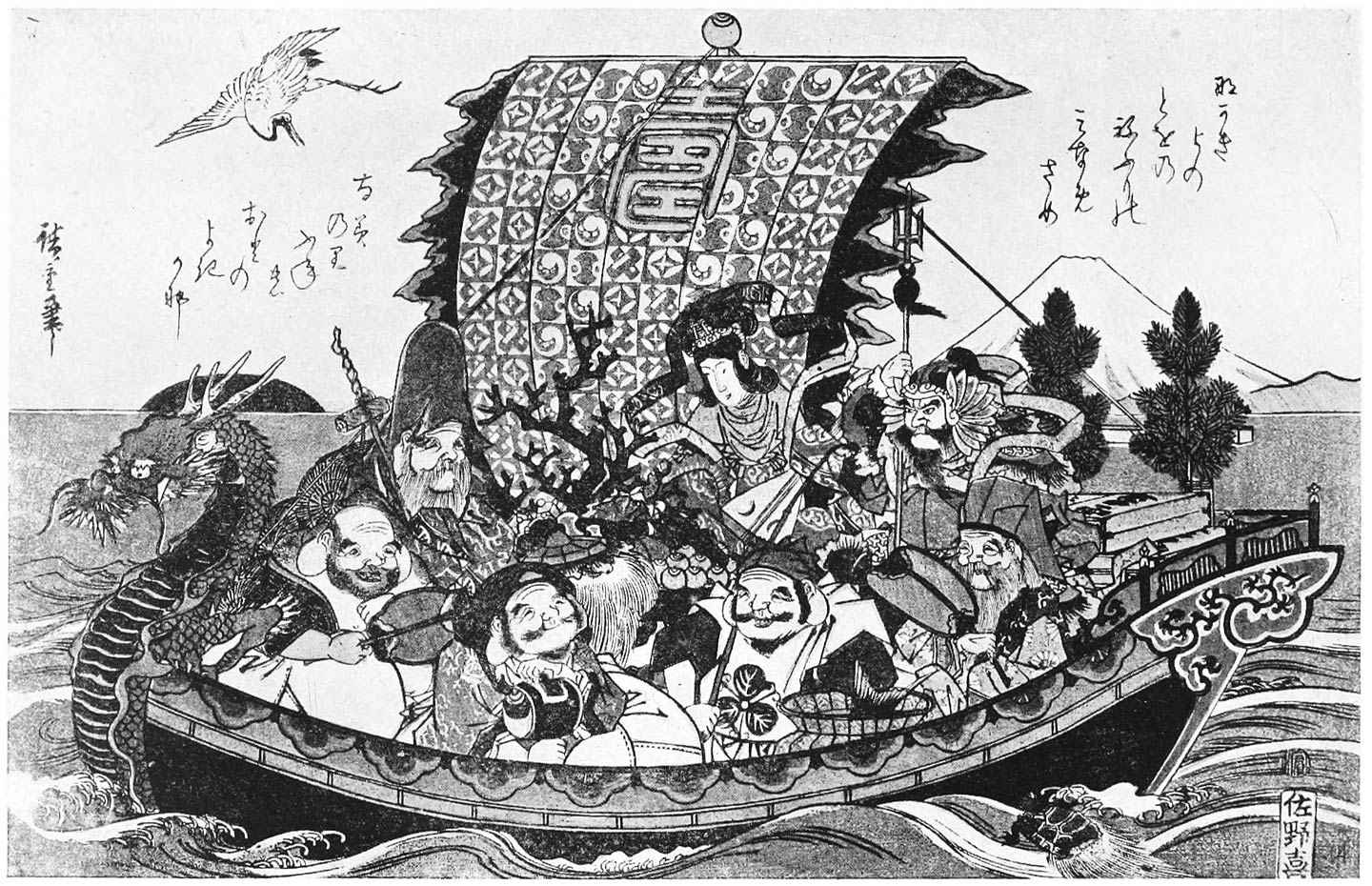

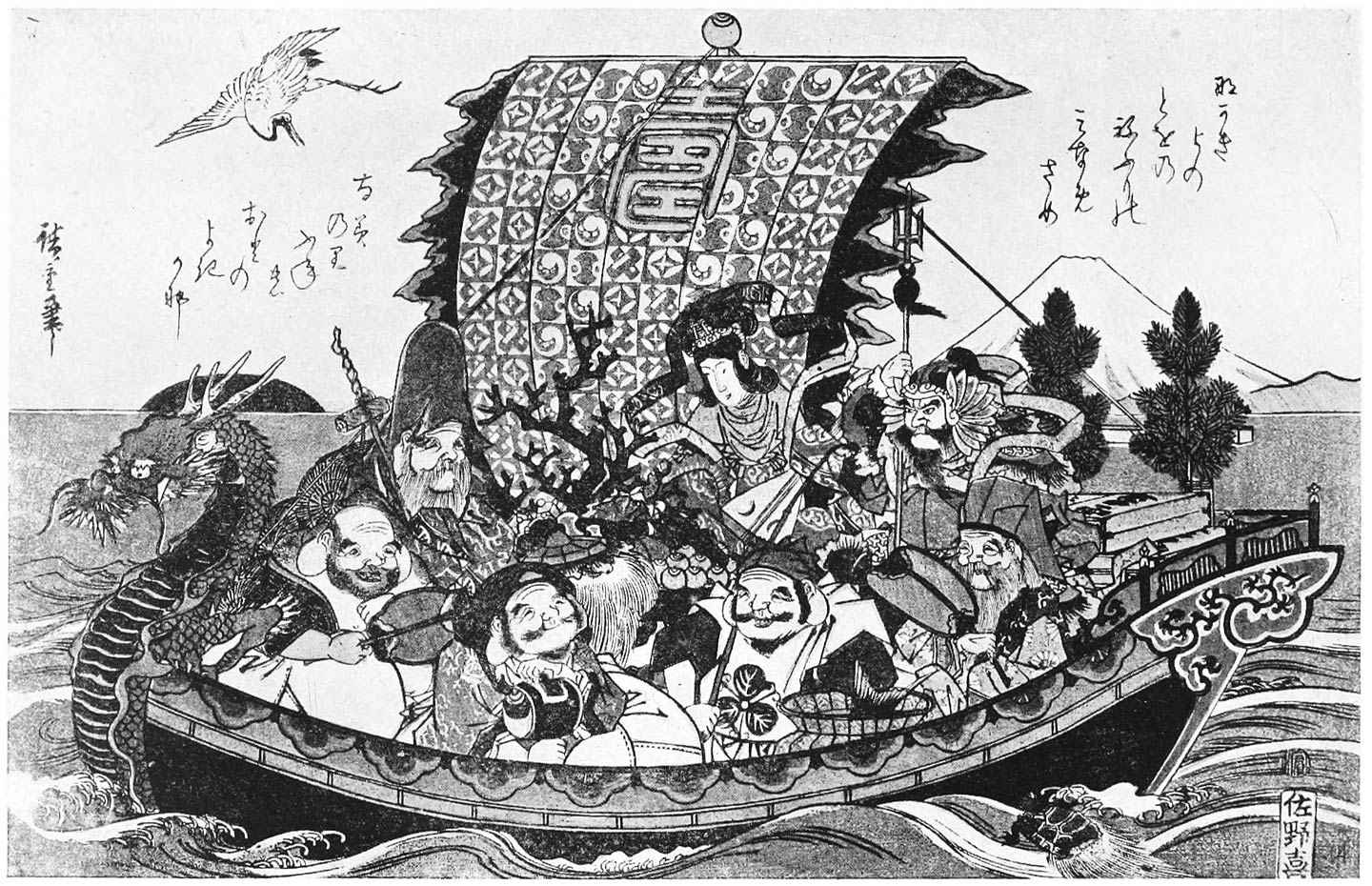

THE JAPANESE TREASURE SHIP

A favourite theme of Japanese art, depicting the Seven Gods (or rather six Gods and one Goddess) of Good Fortune. This illustration is from a woodcut in the British Museum.

In the Ko-ji-ki two groups of eight deities are followed by “the Deity Bird’s-Rock-Camphor-Tree-Boat”, another name for this kami being “Heavenly Bird-Boat”. Then came the food-goddess, “Deity Princess-of-Great-Food”. She was followed by the fire-god, kagu-tsuchi. This deity caused the death of his mother Izanami, having burned her at birth so severely that she sickened [35]and “lay down”. Before she died, an interesting group of deities, making a total of eight from “Heavenly Bird-Boat” to the last named, “Luxuriant Food Princess”, came into being. From her vomit sprang “Metal-Mountain Prince” and “Metal-Mountain Princess”; from her fæces came “Clay Prince” and “Clay Princess” (earth deities); and from her urine crept forth Mitsu-ha no-Me, which Japanese commentators explain as “Female-Water-snake”, or “The Woman who produces the Water”. In the first rendering ha is regarded as meaning “snake” (dragon), and in the second as “to produce”. Neither Florenz nor De Visser can decide which explanation is correct.20 The dragon was, of course, a water-producer, or water-controller, or a “water-confiner”, who was forced to release the waters, like the “drought demon”, slain by the Aryo-Indian god Indra, and the water-confiner of the Nile, whose blood reddened the river during inundation.

When Izanami died, the heart of Izanagi was filled with wrath and grief. Drawing his big sabre, he, according to the Ko-ji-ki, cut off the head of the fire-god; or, as the Nihon-gi tells, cut him into three pieces, each of which became a god. Other gods sprang from the pieces, from the blood drops that bespattered the rocks, the blood that clung to the upper part of the sabre, and the blood that leaked out between the fingers of Izanagi.

According to the Nihon-gi, the blood dripping from the upper part of the sword became the gods Kura-okami, Kura-yama-tsumi, and Kura-mitsu-ha. The meaning of the character kura is “dark”, and Professor Florenz explains it as “abyss, valley, cleft”,21 and notes that okami means [35]“rain” and “dragon”. According to De Visser, Kura-okami is a dragon- or snake-god who controls rain and snow, and had Shinto temples “in all provinces”. Another reading in the Nihon-gi states that one of the three gods who came into being from the pieces of the fire-god’s body was Taka-okami, a name which, according to a Japanese commentator, means “the dragon-god residing on the mountains”, while Kura-okami means “the dragon-god of the valleys”.22 The second god born from the blood drops from the upper part of the sword, Kura-yama-tsumi, is translated “Lord of the Dark Mountains”, and “Mountain-snake”; and the third, Kura-mitsu-ha, is “Dark-water-snake” or “Valley-water-snake”. According to the Ko-ji-ki, the deities Kura-okami and Kura-mitsu-ha came from the blood that leaked out between Izanagi’s fingers.

It is of interest to note here that other dragon deities to which Izanagi and Izanami gave origin, included the mizuchi or “water fathers”, which are referred to as “horned deities”, “four-legged dragons”, or “large water-snakes”. As Aston notes,23 these “water fathers” had no individual names; they were prayed to for rain in times of drought. Another sea-dragon child of the great couple was the wani, which appears to have been a combination of crocodile and shark. Aston thinks that wani is a Korean word. De Visser, on the other hand, is of opinion that the wani is the old Japanese dragon-god or sea-god, and that the legend about the Abundant Pearl Princess (Toyo-tama-bime)24 who had a human lover and, like Melusina, transformed herself from human shape into that of a wani (Ko-ji-ki) or a dragon (Nihon-gi), was originally a Japanese serpent-dragon, which was “dressed in Indian garb by later generations”.25 Florenz, the German Orientalist, thinks the legend is of Chinese origin, but a similar one is found in Indonesia. “Wani,” De Visser says, “may be an Indonesian word,” and it is possible, as he suggests, that “foreign invaders, who in prehistoric times conquered Japan, came from Indonesia and brought the myth with them.”26

There is a reference in the Nihon-gi (Chapter I) to a “bear-wani, eight fathoms long”, and it has been suggested that “bear” means here nothing more than “strong”.27 The Ainu, however, as we have seen (Chapter XVII), associated bear and dragon deities; the bear-goddess was the wife of the dragon-god, and that goddess had, like the Abundant Pearl Princess, a human lover. “Bear-wani” may therefore have been a bear-dragon. There was a dragon-horse “with a long neck and wings at its sides”, which flew through the air, and did not sink when it trod upon the water,28 and there were withal Japanese crow-dragons, toad-dragons, fish-dragons, and lizard-dragons.

The horse played as prominent a part in Japanese rain-getting and rain-stopping ceremonies as did the bear among the Ainu. White, black, or red horses were offered to bring rain, but red horses alone were sacrificed to stop rain. Like the Buriats of Siberia and the Aryo-Indians of the Vedic period, the Japanese made use of the domesticated horse at the dawn of their history. No doubt it was imported from Korea. There is evidence that at an early period human beings were sacrificed to the Japanese dragon-gods of rivers, lakes, and pools. Human sacrifices at tombs are also referred to. In the Nihon-gi, under the legendary date 2 B.C., it is related that when a Mikado died his personal attendants were buried alive in an upright position beside his tomb.29

In his notable work on the dragon, M. W. de Visser30 shows that the Chinese ideas regarding their four-legged dragon and Indian Buddhist ideas regarding nagas were introduced into Japan and fused with local ideas regarding serpent-shaped water-gods. The foreign elements added to ancient Japanese legends have, as has been indicated, made their original form obscure. In the dragon place-names of Japan, however, it is still possible to trace the locations of the ancient Shinto gods who were mostly serpent-shaped. An ancient name for a Japanese dragon is Tatsu. De Visser notes that Tatsu no Kuchi (“Dragon’s mouth”) is a common place-name. It is given to a hot spring in the Nomi district, to a waterfall in Kojimachi district, to a hill in Kamakura district, where criminals were put to death, and to mountains, &c., elsewhere. Tatsu ga hana (“Dragon’s nose”) is in Taga district; Tatsukushi (“Dragon’s skewer”) is a rock in Tosa province; and so on. Chinese and Indian dragons are in Japanese place-names “ryu” or “ryo”. These include Ryo-ga-mine (“Dragon’s peak”) in Higo; Ryu-ga-take (“Dragon’s peak”) in Ise; Ryu-kan-gawa (“Dragon’s rest river”) in Tokyo, &c.

The worship of the Water Fathers or Dragons in Japan was necessary so as to ensure the food-supply.