CHAPTER XXI

ANCIENT MIKADOS AND HEROES

End of Dynasty of Susa-no-wo—Dynasty of Sun-goddess—The First Emperor of Japan—Mikado as Descendant of the Sea-god, the “Abundant Pearl Prince”—A Japanese Gilgamesh—Quest of the Orange Tree of Life—The “Eternal Land”—The Polynesian Paradise and Tree of Life—Yamato-Take, National Hero of Japan—Conflicts with Gods and Rebels—Enchantment and Death of Hero—The Bird-soul—Empress Jingo—Mikado deified as God of War—Shinto Religion and Nature-worship—The Goddess Cult in Japan—Adoration of the Principle of Life in Jewels, Trees, Herbs, &c.—Buddhism—Revival of Pure Shinto—Culture-mixing in China and Japan—China “not a nation”.

Many children were born to Ohonamochi, but the Celestials would not give recognition to the Dynasty of Susa-no-wo, and resolved that Ninigi, the august grandchild of the sun-goddess, should rule Japan. Ohonamochi was deposed, and several deities were sent down from heaven to pacify the land for the chosen one.

Ninigi’s wife was Konohana-sakuyahime, and two of their children were Hohodemi, the hunter, and Ho-no-Susori, the fisherman.

It was Hohodemi who wooed and wed the “Abundant Pearl Princess” and lived with her for a time in the land under the ocean.1 After she gave birth to her child, she departed to her own land, deeply offended because her husband beheld her in dragon (wani) shape in the parturition house he had built for her on the seashore.

This child was the father of the first Emperor of Japan, Jimmu Tenno.2 The Mikados were therefore descended from the sun-goddess Ama-terâsu and the Dragon-king of Ocean, the “Abundant Pearl Prince”.

When engaged pacifying the land, Jimmu followed a gigantic crow3 that had been sent down from heaven to guide him. He possessed a magic celestial cross-sword and a fire-striker. His two brothers, who accompanied him on an expedition across the sea, leapt overboard when a storm was raging so that the waves might be stilled. They were subsequently worshipped as gods.

Yamato now becomes the centre of the narrative, Idzumo having lost its former importance.

Jimmu Tenno reigned until he was 127 years of age, dying, according to Japanese dating, in 585 B.C. His successor was Suisei Tenno. There follows a blank of 500 years which is bridged by the names of rulers most of whom had long lives, some reaching over 120 years.

At the beginning of the Christian era, the Mikado was Sui-nin, who died at the age of 141 years. This monarch sent the hero Tajima-mori to the Eternal Land with purpose to bring back the fruit of the “Timeless (or Everlasting) Fragrant Tree”. The Japanese Gilgamesh succeeded in his enterprise. According to the Ko-ji-ki:

“Tajima-mori at last reached that country, plucked the fruit of the tree, and brought of club-moss eight and of spears eight; but meanwhile the Heavenly Sovereign had died. Then Tajima-mori set apart of club-moss four and of spears four, which he presented to the Great Empress, and set up of club-moss four and of spears four as an offering at the door of the Heavenly Sovereign’s august mausoleum, and, raising on high the fruit of the tree, wailed and wept, saying: ‘Bringing the fruit of the Everlasting Fragrant Tree from the Eternal Land, I have come to serve thee.’ At last he [38]wailed and wept himself to death. This fruit of the Everlasting Fragrant Tree is what is now called the orange.”

Chamberlain explains4 that “club-moss oranges” signifies oranges as they grow on the branch surrounded by leaves, while spear-oranges are the same divested of leaves and hanging to the bare twig.

The location of the Eternal Land has greatly puzzled native scholars. Some suppose it was a part of Korea and others that it was Southern China or the Loocho Islands. According to the Nihon-gi, Tajima-mori found the Eternal Land to be inhabited by gods and dwarfs. As it lay somewhere to the west of Japan, it would appear to be identical with the Western Paradise which, according to Chinese belief, is ruled over by Si Wang Mu (the Japanese Seiobo), the “Royal Mother” and “Queen of Immortals”. Instead of the Chinese Peach Tree of Life, the Japanese had in their own Western Paradise the Orange Tree of Life. The orange was not, however, introduced into Japan until the eighth century of our era.5 Whether or not it supplanted in the Japanese paradise an earlier tree, as the cassia tree supplanted the peach tree in the Chinese paradise, is at present uncertain. It may be that the idea of the Western Paradise was introduced by the Buddhists. At the same time, it will be recalled that the Peach Tree of Life grew on the borderland of Yomi, which was visited by Izanagi.

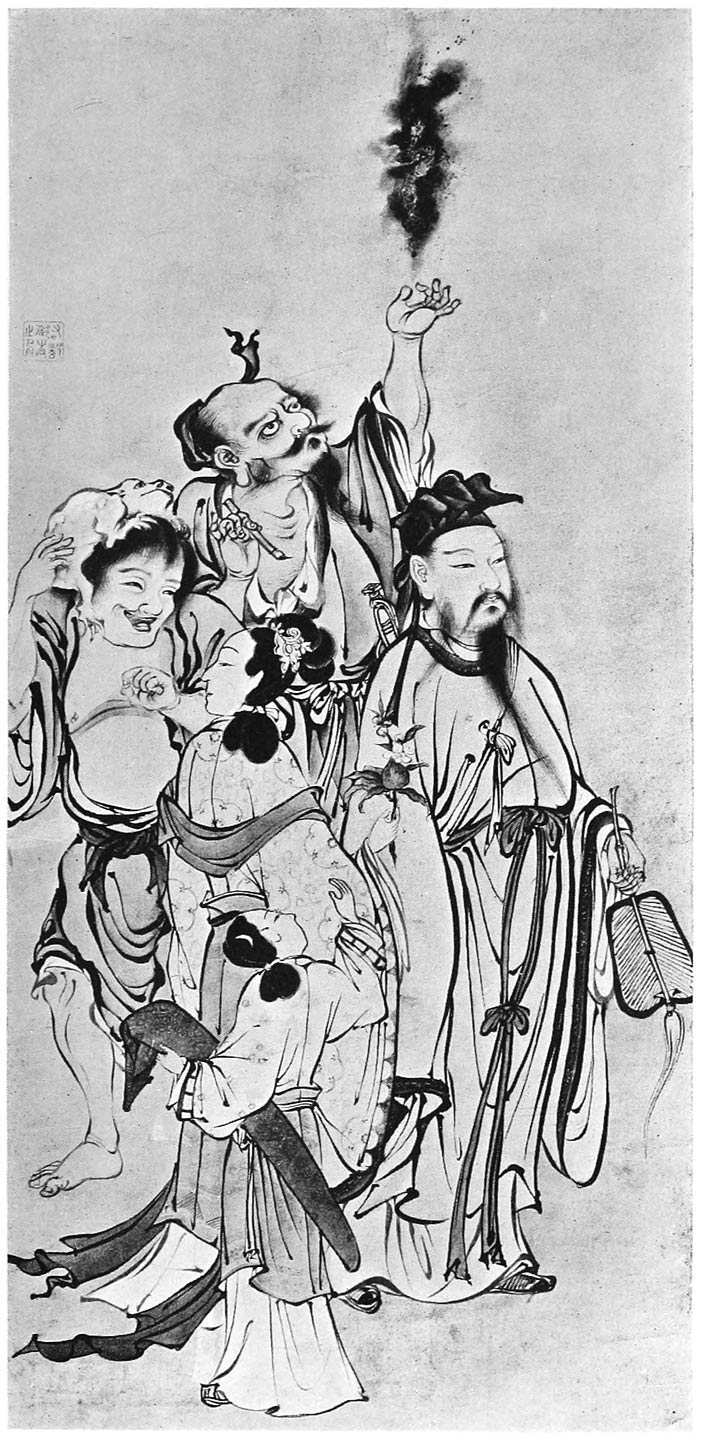

SEIOBO (= THE CHINESE SI WANG MU) WITH ATTENDANT AND THREE RISHI

From a Japanese painting (by Sanraku) in the British Museum

A similar garden paradise was known to the Polynesians, and especially the Tahitians. It was called Rohutu noanoa (“Perfumed or Fragrant Rohutu”). Thither the souls of the dead were conducted by the god [38]Urutaetae. This paradise “was supposed”, writes Ellis,6 “to be near a lofty and stupendous mountain in Raiatea, situated in the vicinity of Hamaniino harbour and called Temehani unauna, ‘splendid or glorious Temehani’. It was, however, said to be invisible to mortal eyes, being in the reva, or aerial regions. The country was described as most lovely and enchanting in appearance, adorned with flowers of every form and hue, and perfumed with odours of every fragrance. The air was free from every noxious vapour, pure, and most salubrious.… Rich viands and delicious fruits were supposed to be furnished in abundance for the frequent and sumptuous festivals celebrated there. Handsome youths and women, purotu anae, all perfection, thronged the place.”

Another Polynesian paradise, called Pulotu, was reserved for chiefs, who obtained “plenty of the best food and other indulgences”. Its ruler, Saveasiuleo, had a human head. The upper part of his body reclined in a great house “in company with the spirits of departed chiefs”, while “the extremity of his body was said to stretch away into the sea in the shape of an eel or serpent”.7

The Japanese had thus, like the Polynesians, a garden paradise and a sea-dragon-king’s paradise, as well as the gloomy Yomi. It may be that the beliefs and stories regarding these Otherworlds were introduced by the earliest seafarers, who formed pearl-fishing communities round their shores. The Ainu believe that Heaven and Hell are beneath the earth, “in Pokna moshiri, the lower world”, but they have no idea what the rewards of the righteous are.8 Nothing is definitely known regarding [38]the beliefs of the earlier and more highly civilized people remembered as the Koro-pok-guru.

The Mikado Sui-nin was succeeded by the Mikado Kei-ko, who died in A.D. 130, aged 143 years. One of his sons, Yamato-Take, is a famous legendary hero of Japan. He performed many heroic deeds in battle against brigands and rebels. At Ise he obtained from his aunt, Yamato-hime, the priestess, the famous Kusanagi sword, and a bag which he was not to open except when in peril of his life. He then set out to subdue and pacify all savage deities and unsubmissive peoples. The ruler of Sagami set fire to a moor which Yamato entered in quest of a “Violent Deity”. Finding himself in peril, he opened the bag and discovered in it a fire-striker (or fire-drill). He mowed the herbage with the dragon-sword, and, using the fire-striker, kindled a counter-fire, which drove back the other fire. The Kusanagi (herb-quelling) sword takes its name from this incident. Yamato-Take afterwards slew the wicked rulers of that land. He also slew a god in the shape of a white deer which met him in Ashigara Pass. He lay in ambush, and with a scrap of chive9 hit the deer in the eye and thus struck it dead. Then he shouted three times “Adzuma ha ya” (Oh, my wife!). The land was thereupon called Adzuma.

Then follows the mysterious story of the death of the hero. He went to the land of Shinanu, in which Ohonamochi had taken refuge when Japan was being subdued for the ruler chosen by the sun-goddess, and where, being pursued and threatened with death, Ohonamochi consented to abdicate and take up his abode in a temple. The country takes its name from shina, a tree resembling the lime,10 and nu or no, “moor”. Yamato-Take entered [38]this land through Shinanu Pass (Shinanu no saka), between the provinces of Shinano and Mino. He overcame the deity of the pass, and went to dwell in the house of Princess Miyazu, of fragrant and slender arms. She welcomed him with love. In the house of the princess he left the Kusanagi sword, and went forth against the deity of evil breath (or influence) on Mount Ibuki. As he climbed the mountain he met a white boar, big as a bull. Believing it was a messenger of the deity, he vowed he would slay it when he returned, and continued to climb the mountain. But the boar was not a messenger; it was the very deity in person, and it sent a heavy ice-rain.11 The rain-smitten and perplexed hero was thus misled by the deity.

On descending the mountain, Yamato-Take reached the fresh spring of Tama-kura-be (the “Jewel-store-tribe”). He drank from it, and revived somewhat. The spring was afterwards called Wi-same (the “well of awakening” or “resting”).

Then Yamato-Take departed, and reached the moor of Tagi,12 lamenting the loss of bodily strength. He passed on to Cape Wotsu in Ise, and there found a sword he had left at a pine tree, and sang:

“O pine tree, my brother,

If thou wert a person,

My sword and my garments

To thee would I give”.

Having sung this song, he proceeded on his way, yearning for his native land, delightful Yamato, situated [38]behind Mount Awogaki. His next song was one of love and regret.

“How sweet o’er the skies

From Yamato, my home,

Do its white clouds arise,

Do its white clouds all come.”

His sickness and weariness made him feel more and more faint, and he sang in his distress:

“Oh! the sharp sabre-sword

I left by the bedside

Of Princess Miyazu—

The sabre-sword”.13

Yamato-Take sank and died as soon as he had finished his song.

In time his wives came and built for him a mausoleum, weeping and moaning the while, because he could not hear them or make answer. Then Yamato-Take was transformed into a white bird,14 which rose high in the air and flew towards the shore. The wives pursued the bird with lamentations and entered the sea. They saw the bird flying towards the beach, and followed it. For a time it perched on a rock. Then it flew from Ise to Shiki, in the land of Kafuchi, where a mausoleum was built for it, so that it might rest.15 But the white bird rose again to heaven and flew away. It was never again seen.

After Mikado Kei-ko, father of Yamato-Take, had passed away, Sei-mu reigned until he was 108 years old. Then followed the Mikado Chiu-ai. His capital was in the south-west on the island of Kyushu. A message [38]came from the goddess through the Empress Jingo, who was divinely possessed, promising him Korea, “a land to the westward” with “abundance of various treasures, dazzling to the eye, from gold and silver downwards”.

The Mikado refused to believe there was a land to the west, and declared that the gods spoke falsely. Soon afterwards the heavenly sovereign was struck dead.

Now the Empress Jingo was with child. Having received the instructions of the deities to conquer Korea for her son, she delayed his birth by taking a stone and attaching it to her waist with cords. Korea was subdued, the Empress having made use of the “Jewels of flood and ebb”, as related in a previous chapter. Her child was born after she returned to Japan.

Empress Jingo is further credited with subduing and uniting the Empire of Japan, and again establishing the central power at Yamato. She lived until she was 100 years old.

Her son Ojin Tenno,16 who had a dragon’s tail, lived until he was 110 years old, and died in A.D. 310. He was worshipped after death as a war-god, and the patron of the Minamoto clan. His successor, Nin-toku, who died at the age of 110, was the last of the mythical monarchs, or of the monarchs regarding whom miraculous deeds are related. Japanese history begins and myth ends about the beginning of the fifth century of the Christian era.

The cult of Hachiman (Ojin Tenno) came into prominence in the ninth century with the rise of the Minamoto family; its original seat was Usa, in Buzen province. Hachiman’s shintai (“god body”) is a white stone, or a fly-brush, or a pillow, or an arm-rest. [38]

Jimmu Tenno, the Empress Jingo, and Yamato-Take were similarly deified and worshipped. A ninth century scholar, Sugahara Michizane, was deified as Temmangû, god of scholars. Living as well as dead Mikados were kami (deities). “The spirits of all the soldiers who died in battle,” writes Yei Ozaki,17 “are worshipped as deified heroes at the Kudan shrine in Tokyo.”

The worship of human ancestors in Japan is due to Chinese influence, and had no place in old Shinto prior to the sixth century. In the Ko-ji-ki and Nihon-gi the ancestors of the Mikados and the ruling classes are the deities and their avatars. As we have seen, the Mikados were reputed to be descended from the sun-goddess, and from the daughter of the Dragon King of Ocean, called the “Abundant-Pearl Princess”, a Japanese Melusina.

It is far from correct, therefore, to refer, as has been done, to Shinto religion as “the worship of nature-gods and ancestors”. Even the term “nature-worship” is misleading. The adoration in sacred shrines of the mi-tama (the “August jewel”, or “Dragon-pearl”, or “spirit”, or “double”) of a deity is not “the worship of Nature”, but the worship of “the imperishable principle of life wherever found”. At Ise, the “Mecca” of Japan, the goddess cult is prominent. Both the sun-goddess and the food-goddess are forms of the Far Eastern Hathor, the personification of the pearl, the shell, the precious jewel containing “life substance”, the sun mirror, the sword, the pillow, the standing-stone, the holy tree, the medicinal herb, the fertilizing rain, &c. The Mikado, as her descendant, was the living Horus, an avatar of Osiris; after death the Mikado ascended, like Ra, to the celestial regions, or departed, like Osiris, to the Underworld of [38]the Dead. The Mikado of Japan, like the Pharaoh of Egypt, was a Son of Heaven.

After Buddhism had been introduced into Japan in the sixth century, it was fused with Shinto. The Shinto deities figured as avatars of Buddha in the cult of Ryobu-Shinto. Even the Mikados came under the spell of Buddhism.

In the eighteenth century began the movement known as the “Revival of Pure Shinto”. It was promoted chiefly by Motöori and his disciple Hirata. In time it did much to bring about the revolution which restored to supreme political power, as the hereditary high priest and living representative of the sun-goddess, the Mikado of Japan. Shinto is the official religion of modern Japan; but Buddhism, impregnated with Shinto elements, is the religion of the masses. “Pure Shinto”, however, was not “pure” in the sense that Motöori and Hirata professed to believe. It was undoubtedly a product of culture mixing in early times. “The Ko-ji-ki and Nihon-gi,” as Laufer says, “do not present a pure source of genuine Japanese thought, but are retrospective records largely written under Chinese and Korean influence, and echoing in a bewildering medley continental-Asiatic and Malayo-Polynesian traditions.”18 In China, Korea, Polynesia, &c., a similar process of culture mixing can be traced. Buddha and Mohammed were not the earliest founders of cults which have left their impress on the religious systems of the Far East. Vast areas were influenced by the cultures of Ancient Egypt and Babylonia.

The history of civilization does not support the hypothesis that the same myths and religious practices were of spontaneous generation in widely-separated countries. Culture complexes cannot be accounted for or explained away by the application of the principles of biological evolution. As has been shown in these pages, there are many culture complexes in China and Japan, and many links with more ancient civilizations.

Touching on the problem of culture mixing in China, Laufer writes:

“In opposition to the prevalent opinion of the day, it cannot be emphasized strongly enough on every occasion that Chinese civilization, as it appears now, is not a unit and not the exclusive production of the Chinese, but the final result of the cultural efforts of a vast conglomeration of the most varied tribes, an amalgamation of ideas accumulated from manifold quarters and widely differentiated in space and time; briefly stated, this means China is not a nation, but an empire, a political, but not an ethnical unit. No graver error can hence be committed than to attribute any culture idea at the outset to the Chinese, for no other reason than because it appears within the precincts of their empire.”19