CHAPTER III

ANCIENT MARINERS AND EXPLORERS

The Chinese Junk—Kufas—The Ancient “Reed Float” and Skin-buoyed Raft—“Two floats of the Sky”—Dug-out Canoes—Where Shipping was developed—Burmese and Chinese Junks resemble Ancient Egyptian Ships—Cretan and Phœnician Mariners—Africa circumnavigated—Was Sumeria colonized by Sea-farers?—Egyptian Boats on Sea of Okhotsk—Japanese and Polynesian Boats—Egyptian Types in Mediterranean and Northern Europe—Stories of Long Voyages in Small Craft—Visit of Chinese Junk to the Thames—Solomon’s Ships.

Further important evidence regarding cultural contact in early times is afforded by shipping. How came it about that an inland people like the primitive Chinese took to seafaring?

The question that first arises in this connection is: Were ships invented and developed by a single ancient people, or were they invented independently by various ancient peoples at different periods? Were the Chinese junks of independent origin? Or were these junks developed from early models of vessels—such foreign vessels as first cruised in Chinese waters?

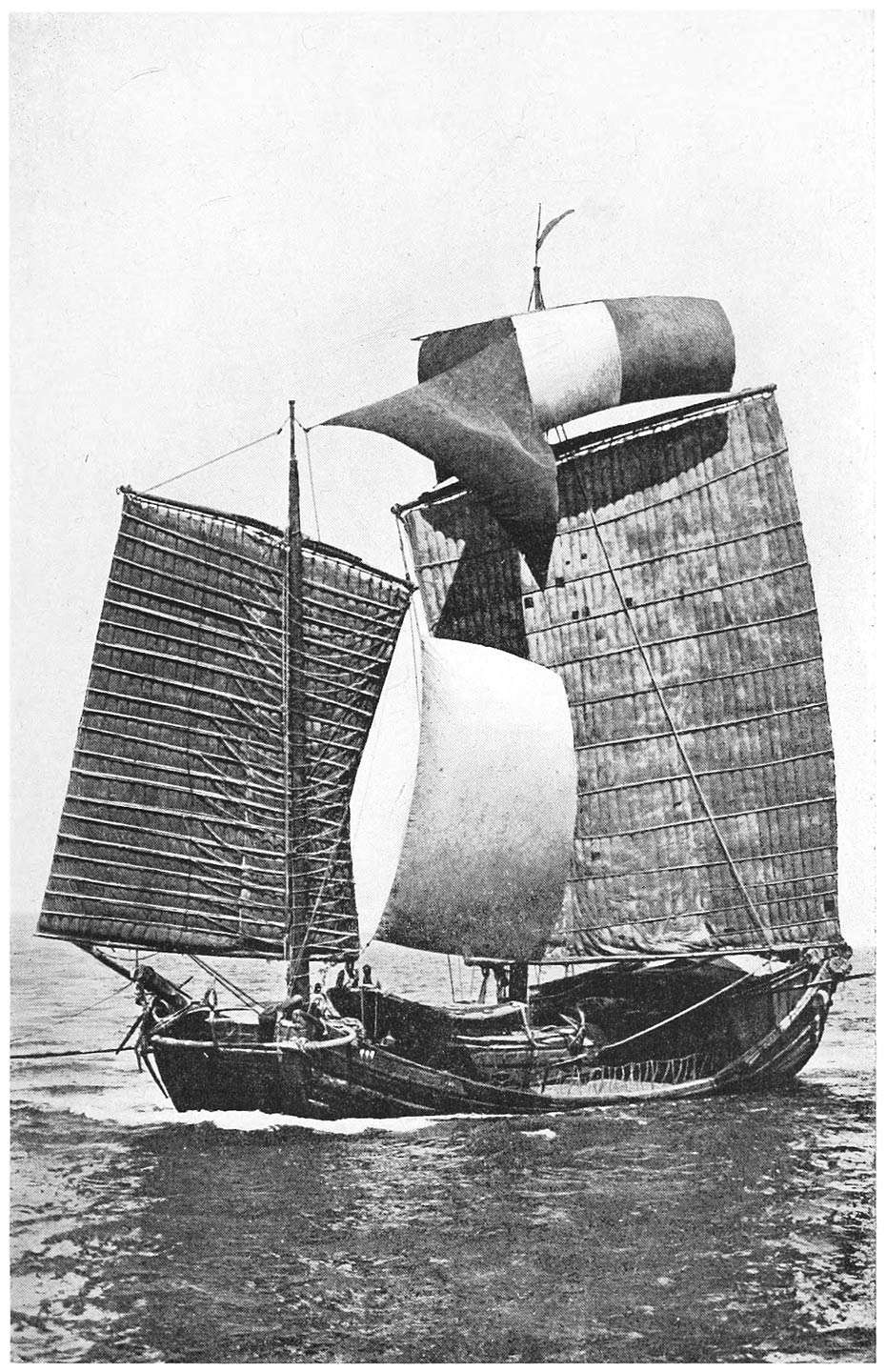

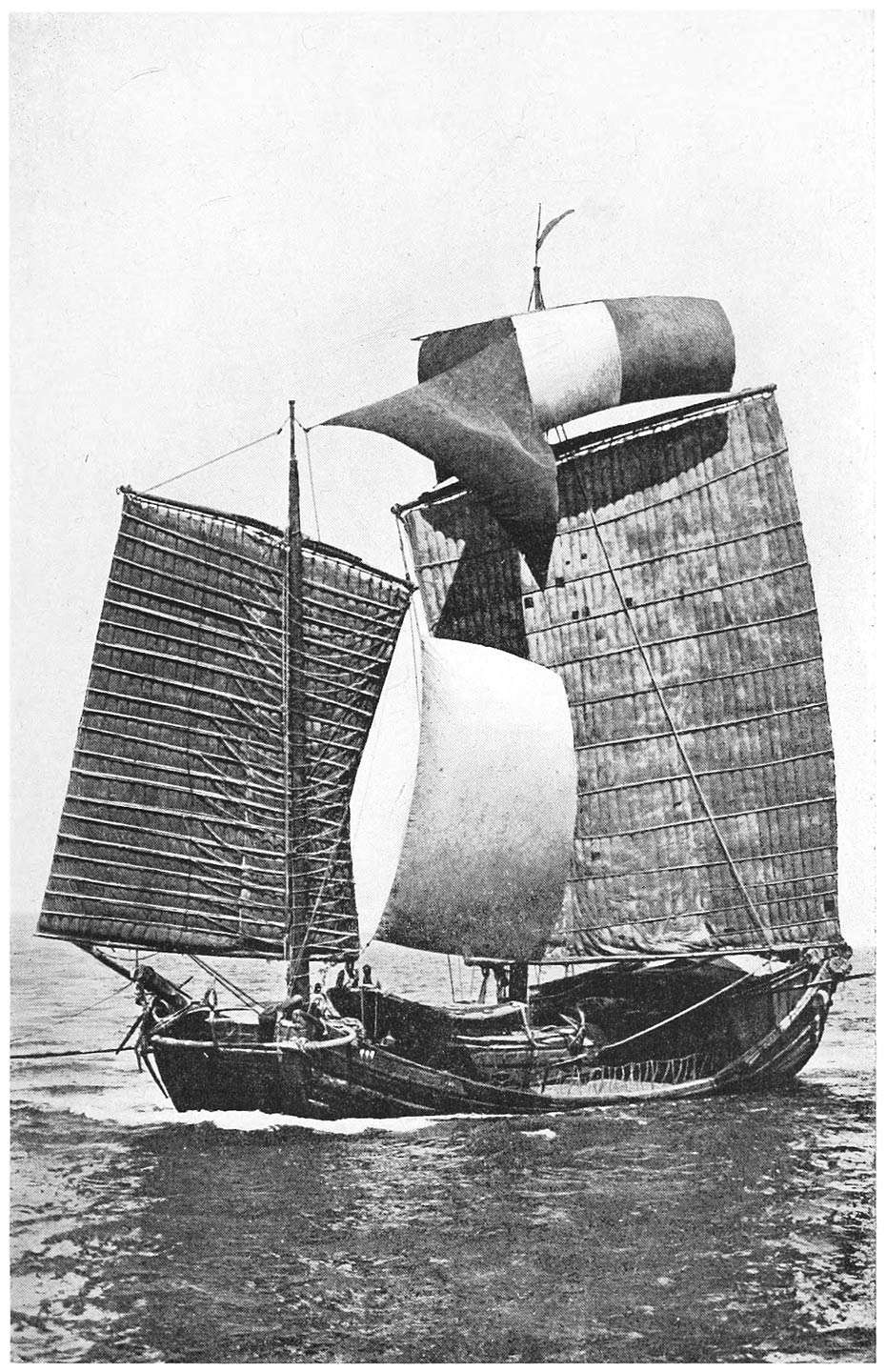

Chinese junks are flat-bottomed ships, and the largest of them reach about 1000 tons. The poops and fore-castles are high, and the masts carry lug-sails, generally of bamboo splits. They are fitted with rudders. Often on the bows appear painted or inlaid eyes. These eyes are found on models of ancient Egyptian ships.

Photo. Underwood

A MODERN CHINESE JUNK ON THE CANTON RIVER

During the first Han dynasty (about 206 B.C.) junks of “one thousand kin” (about 15 tons) were regarded as very large vessels. In these boats the early Chinese navigators appear to have reached Korea and Japan. But long before they took to the sea there were other mariners in the China sea.

The Chinese were, as stated, originally an inland people. They were acquainted with river kufas (coracles) before they reached the seashore. These resembled the kufas of the Babylonians referred to by Herodotus, who wrote:

“The boats which come down the river to Babylon are circular, and made of skins. The frames, which are of willow, are cut in the country of the Armenians above Assyria, and on these, which serve for hulls, a covering of skins is stretched outside, and thus the boats are made, without either stem or stern, quite round like a shield.”1

These kufas are still in use in Mesopotamia. They do not seem to have altered much since the days of Hammurabi, or even of Sargon of Akkad. The Assyrians crossed rivers on skin floats, and some of the primitive peoples of mid-Asia are still using the inflated skins of cows as river “ferry-boats”. But such contrivances hardly enter into the history of shipping. The modern liner did not “evolve” from either kufa or skin float. Logs of wood were, no doubt, used to cross rivers at an early period. The idea of utilizing these may have been suggested to ancient hunters who saw animals being carried down on trees during a river flood. But attempts to utilize a tree for crossing a river would have been disastrous when first made, if the hunters were unable to swim. Trees are so apt to roll round in water. Besides, they would be useless if not guided with a punting-pole, expertly manipulated. Early man must have learned how to navigate a river by using, to begin with, at least two trees lashed together. In Egypt and Babylonia we find traces of his first attempts in this connection. The reed float, consisting of two bundles of reeds, and the raft to which the inflated skins of animals were attached to give it buoyancy, were in use at an early period on the Rivers Nile and Euphrates. A raft of this kind had evidently its origin among a people accustomed, as were the later Assyrians, to use skin floats when swimming across rivers. There are sculptured representations of the Assyrian soldiers swimming with inflated skins under their chests.

The reed float was in use at a very early period on the Nile. Professor Breasted says that the two prehistoric floats were “bound firmly together, side by side, like two huge cigars”, and adds the following interesting note: “The writer was once without a boat in Nubia, and a native from a neighbouring village at once hurried away and returned with a pair of such floats made of dried reeds from the Nile shores. On this somewhat precarious craft he ferried the writer over a wide channel to an island in the river. It was the first time that the author had ever seen this contrivance, and it was not a little interesting to find a craft which he knew only in the Pyramid texts of 5000 years ago still surviving and in daily use on the ancient river in far-off Nubia.”

In the Pyramid texts there are references to the reed floats used by the souls of kings when being ferried across the river to death. The gods “bind together the two floats for this King Pepi”, runs a Pyramid text. “The knots are tied, the ferry-boats are brought together”, says another, and there are allusions to the ferryman (the prehistoric Charon) standing in the stern and poling the float. Before the Egyptian sun-god was placed in a boat, he had “two floats of the sky” to carry him along the celestial Nile to the horizon.2

The “dug-out” canoe was probably developed from the raft. Men who drifted timber down a river may have had the idea of a “dug-out” suggested to them by first shaping a seat on a log, or a “hold” to secure the food-supply for the river voyage. Pitt Rivers suggests that after the discovery was made that a hollowed log could be utilized in water, “the next stage in the development of the canoe would consist in pointing the ends”.3

In what locality the dug-out canoe was invented it is impossible to say with absolute certainty. All reliable writers on naval architecture agree, however, that Egypt was the “cradle” of naval architecture.4

“For the development of the art of shipbuilding,” says Chatterton, “few countries could be found as suitable as Egypt.… The peacefulness of the waters of the Nile, the absence of storms, and the rarity of calms, combined with the fact that, at any rate, during the winter and early spring months, the gentle north wind blew up the river with the regularity of a Trade Wind, so enabling the ships to sail against the stream without the aid of oars—these were just the conditions that many another nation might have longed for. Very different, indeed, were the circumstances which had to be wrestled with in the case of the first shipbuilders and sailormen of Northern Europe.”5

The early Egyptians were continually crossing the river. When they began to convey stones from their quarries, they required substantial rafts. Egyptian needs promoted the development of the art of navigation on a river specially suited for experiments that led to great discoveries. The demand for wood was always great, and it was intensified after metal-working had been introduced, because of the increased quantities of fuel required to feed the furnaces. It became absolutely necessary for the Egyptians to go far afield in search of timber. The fact that they received supplies of timber at an early period from Lebanon is therefore of special interest. Their experiences in drifting rafts of timber across the Mediterranean from the Syrian coast apparently not only stimulated naval architecture and increased the experiences of early navigators, but inaugurated the habit of organizing seafaring expeditions on a growing scale. “Men”, says Professor Elliot Smith, “did not take to maritime trafficking either for aimless pleasure or for idle adventure. They went to sea only under the pressure of the strongest incentives.”6

The Mediterranean must have been crossed at a very early period. Settlements of seafarers took place in Crete before 3000 B.C.7 On the island have been found flakes of obsidian that were imported at the dawn of its history from the Island of Melos. No doubt obsidian artifacts were used in connection with the construction of vessels before copper implements became common.

The earliest evidence of shipbuilding as an organized and important national industry is found in the Egyptian tomb pictures of the Old Kingdom period (c. 2400 B.C.). Gangs of men, under overseers, are seen constructing many kinds of boats, large and small. There are records of organized expeditions dating back 500 years earlier. Pharaoh Snefru built vessels “nearly one hundred and seventy feet long”. He sent “a fleet of forty vessels to the Phœnician coast to procure cedar logs from the slopes of Lebanon”.8 Expeditions were also sent across the Red Sea. Vessels with numerous oars, and even vessels with sails, are depicted on Egyptian prehistoric pottery dating back to anything like 6000 B.C. In no other country in the world was seafaring and shipbuilding practised at such a remote period.

The earliest representations of deep-sea boats are found in Egypt. One is seen in the tomb of Sahure, of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2600 B.C.). A great expedition sailed to Punt (Somaliland) during the reign of Queen Halshepsut (c. 1500 B.C.). Five of the highly-developed vessels are depicted in her temple at Deir-el-Bahari. It is of interest to compare one of these vessels with a Chinese junk. “Between the Chinese and Burmese junks of to-day and the Egyptian ships of about six thousand years ago there are”, writes E. Kebel Chatterton, “many points of similarity.… Until quite recently, China remained in the same state of development for four thousand years. If that was so with her arts and life generally, it has been especially so in the case of her sailing craft.” Both the Chinese junk and the ancient Egyptian ship “show a common influence and a remarkable persistence in type”.9

“Are we to believe”, a reader asks, “that the ancient Egyptian navigators went as far as China? Is there any proof that they made long voyages? Were the ancient Egyptians not a people who lived in isolation for a prolonged period?”10

It is not known definitely how far the ancient Egyptian mariners went after they had begun to venture to sea. But one thing is certain. They made much longer voyages than were credited to them a generation ago. The Phœnicians, who became the sea-traders of the Egyptians, learned the art of navigation from those Nilotic adventurers who began to visit their coast at a very early period in quest of timber; they adopted the Egyptian style of craft, as did the Cretans, their predecessors in Mediterranean sea trafficking. By the time of King Solomon the Phœnicians had established colonies in Spain, and were trading not only from Carthage in the Mediterranean, but apparently with the British Isles, while they were also active in the Indian Ocean. They were evidently accustomed to make long voyages of exploration. At the time of the Jewish captivity, Pharaoh Necho (609–593 B.C.) sent an expedition of Phœnicians from the Red Sea to circumnavigate Africa. They returned three years later by way of Gibraltar. But their voyage excited no surprise in Egypt.11 It had long been believed by the priests that the world was surrounded by water. Besides, these priests preserved many traditions of long voyages that had been made to distant lands.

There are those who believe that the early Egyptian mariners, who were accustomed to visit British East Africa and sail round the Arabian coast, founded the earliest colony in Sumeria (ancient Babylonia) at the head of the Persian Gulf. The cradle of Sumerian culture was Eridu, “the sea port”. The god of Eridu was Ea, who had a ship with pilot and crew. According to Babylonian traditions, he instructed the people, as did Osiris in Egypt, how to irrigate the land, grow corn, build houses and temples, make laws, engage in trade, and so on. He was remembered as a monster—a goat-fish god, or half fish, half man. Apparently he was identical with the Oannes of Berosus. It may be that Ea-Oannes symbolized the seafarers who visited the coast and founded a colony at Eridu, introducing the agricultural mode of life and the working of copper. Early inland peoples must have regarded the mariners with whom they first came into contact as semi-divine beings, just as the Cubans regarded Columbus and his followers as visitors from the sky. The Mongols of Tartary entertained quaint ideas about the British “foreign devils” after they had fought in one of the early wars against China. M. Huc, the French missionary priest of the congregation of St. Lazarus, who travelled through Tartary, Tibet, and China during 1844–6, had once an interesting conversation with a Mongol, who “had been told by the Chinese what kind of people, or monsters rather, these English were”. The story ran that the Englishmen “lived in the water like fish, and when you least expected it, they would rise to the surface and cast at you fiery gourds. Then as soon as you bend your bow to send an arrow at them, they plunge again into the water like frogs.”12

Those who suppose that the Sumerians coasted round from the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea, landed on the barren African coast, and, setting out to cross a terrible desert, penetrated to the Nile valley along a hitherto unexplored route of about 200 miles, have to explain what was the particular attraction offered to them by prehistoric Egypt if, according to their theory, it was still uncultivated and in the “Hunting Age”. How came it about that they knew of a river which ran through desert country?

It is more probable that the Nilotic people penetrated to the Red Sea coast, and afterwards ventured to sea in their river boats, and that, in time, having obtained skill in navigation, they coasted round to the Persian Gulf. In pre-Dynastic times the Egyptians obtained shells from the Red Sea coast.

At what period India was first reached is uncertain. When Solomon imported peacocks from that country (the land of the peacock), the sea route was already well known. It is significant to find that all round the coast, from the Red Sea to India, Ceylon, and Burma, the Egyptian types of vessels have been in use from the earliest seafaring periods. The Burmese junks on the Irawadi resemble closely, as has been indicated, the Nile boats of the ancient Egyptians.13 The Chinese junks were developed from Egyptian models. More antique Egyptian boats than are found on the Chinese coast are still being used by the Koryak tribe who dwell around the sea of Okhotsk. Mr. Chatterton says that the Koryak craft have “important similarities to the Egyptian ships of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties (c. 3000–2500 B.C.). Thus, besides copying the ancients in steering with an oar, the fore-end of the prow of their sailing boats terminates in a fork through which the harpoon-line is passed, the fork being sometimes carved with a human face which they believe will serve as a protector of the boat. Instead of rowlocks they have, like the early Egyptians, thong-loops through which the oar or paddle is inserted. Their sail, too, is a rectangular shape of dressed reindeer skins sewed together. But it is their mast that is especially like the Egyptians and Burmese.” This mast is made of three poles “set up in the manner of a tripod”. The double mast was common in ancient Egypt, but Mr. Chatterton notes that Mr. Villiers Stuart “found on the walls of a tomb belonging to the Sixth Dynasty (c. 2400 B.C.) at Gebel Abu Faida, the painting of a boat with a treble mast made of three spars arranged like the edges of a triangular pyramid”.14 Thus we find that vessels of Egyptian type (adopted by various peoples) not only reached China but went a considerable distance beyond it. Japanese vessels still display Egyptian characteristics. In the Moluccas and Malays the ancient three-limbed mast has not yet gone out of fashion. Polynesian craft were likewise developed from Egyptian models. William Ellis, the missionary,15 noted “the peculiar and almost classical shape of the large Tahitian canoes”, with “elevated prow and stern”, and tells that a fleet of them reminded him of representations of “the ships in which the Argonauts sailed, or the vessels that conveyed the heroes of Homer to the siege of Troy”.

Various writers have called attention to the persistence of Egyptian types in the Mediterranean and in northern Europe. “In every age and every district of the ancient world”, wrote Mr. Cecil Torr, the great authority on classic shipping, “the method of rigging ships was substantially the same; and this method is first depicted by the Egyptians.”16

The Far Eastern craft went long distances in ancient days. Ellis tells of regular voyages made by Polynesian chiefs which extended to 300 and even 600 miles. A chief from Rurutu once visited the Society Islands in a native boat built “somewhat in the shape of a crescent, the stem and stern high and pointed and the sides deep”.17 Sometimes exceptionally long voyages were forced by the weather conditions of Oceania. “In 1696”, Ellis writes, “two canoes were driven from Ancarso to one of the Philippine Islands, a distance of 800 miles.” He gives other instances of voyages of like character. A Christian missionary, travelling in a native boat, was carried “nearly 800 miles in a south-westerly direction”.18 Reference has already been made to the long and daring voyage made by the Phœnicians who circumnavigated Africa. Another extraordinary enterprise is referred to by Pliny the elder,19 who quotes from the lost work of Cornelius Nepos. This was a voyage performed by Indians who had, before 60 B.C., embarked on a commercial voyage and reached the coast of Germany. It is uncertain whether they sailed round the Cape of Good Hope and up the Atlantic Ocean, or went northward past Japan and discovered the north-east passage, skirting the coast of Siberia, and sailing round Lapland and Norway to the Baltic. They were made prisoners by the Suevians and handed over to Quintus Metellus Celer, pro-consular governor of Gaul.

In 1770 Japanese navigators reached the northern coast of Siberia and landed at Kamchatka. They were taken to St. Petersburg, where they were received by the Empress of Russia, who treated them with marked kindness. In 1847–8 the Chinese junk Keying sailed from Canton to the Thames and caused no small sensation on its arrival. This vessel rounded the Horn and took 477 days to complete the voyage.

Solomon’s ships made long voyages: “Once every three years came the navy of Tarshish, bringing gold, and silver, ivory, and apes, and peacocks”.20

As in the case of the potter’s wheel, cultural elements were distributed far and wide by the vessels of the most ancient of mariners. Before tracing these elements in China, it would be well to deal with the motives that impelled early seafarers to undertake long and adventurous voyages of exploration and to found colonies in distant lands.