CHAPTER XVIII.

Well, Tamer and I had it all planned to go to Uncle Submit’s whilst Celestine wuz there with her little girl, but at the last minute a letter come from Tamer askin’ me if I wouldn’t come there and visit with Celestine, as she had concluded to invite her there instead of our goin’ to see her. There wuz some views, Tamer said, about their house that Celestine wanted to paint, and had jest as good as told her it would be more agreeable for us all to visit there than at Uncle Submit’s. “Pretty cool in Celestina,” sez Tamer.

She always put on the “teeny,” but, good land! I didn’t. I knew she wuz named Celestine after old Aunt Celestine Butterick. I wuzn’t goin’ to add or diminish from that good old creeter’s name, so I always called her Celestine.

Well, Tamer went on to say that, though it wuz pretty cool in Celestina, but jest like her for all the world, mebby it would be better for us to meet there, as Uncle Submit and Aunt Eunice wuz kinder childish and mebby so many visitors would upset ’em, and Celestina is all took up with her painting, and hain’t any housekeeper, and the hired girl is a real shiftless one. And sez Tamer, “Be sure you come prepared to stay a week, the children are jest cryin’ to have you come. Anna sez, ‘Tell Aunt Samantha she must stay a week anyway,’ and Jack has wrote you a letter which I enclose in this. Cicero would send a message, but he is dretful carried away with a new book he has borrowed, a splendid book, ‘The Serpent Enchantress; or, The Doomed Fly-Away,’ it is perfectly fascinating. I set up last night until four o’clock finishin’ it.”

I gin a deep sithe as I read this sentence. The letter closed with another urgent request for to come when she give me warnin’, she would write the day Celestina come, she said, and it ended

“Yours with devoted love,

“TAMER SMITH.”

I laid down her epistle and took up Jack’s, it wuz printed in big letters, and the page wuz as full of love and longin’ to see me as it wuz with smears and ink blots, and that is goin’ to the very extent of describin’ the love it contained. Bless his dear little warm heart! Well, I spozed I should have to go but thought I wouldn’t talk it over with Josiah till the day drawed near, not wantin’ to precipitate trouble onto him till it wuz necessary, and I knew well how wedded he wuz to my presence.

And the next day I begun quietly and prudently to prepare for the great Charity Bazar of Miss Greene Smythe’s. I bound over my best woosted petticoat that wuz some frayed out round the bottom, and mended a few broken places in the tattin’ that trimmed my white one. I took the lace out of the neck and sleeves of my gray woosted dress, which I laid out to wear instead of my black alpacky, thinkin’ it looked more gay and cheerful and more adapted to the requirements of a fashionable party in high life, I washed the lace carefully and did it up and put it back, crimpin’ it on the edge as I did so. I pondered on the enigma some time whether I should look too gay, and go beyend the other church members present, if I pinned on in front a satin bow of kinder pink ribbon that Maggie had gin me, I held it up to the dress and see in the lookin’-glass it looked well, but mebby a little too flantin’ and frivolous, so I laid it back agin in the draw and made up my mind I would wear my good old cameo pin, knowin’ that wuz safe for a Methodist member to wear anyway, and I didn’t want to cause comments or roust up the envy and jealousy of the other females present.

Anon and pretty soon the night come for the great Bazar for that Heathen, and Josiah and I started in good season, for we didn’t want the mair and colt to be hurried, nor be hurried ourselves. We started about half-past four P. M. I got a early breakfast that mornin’ a-purpose to git a early dinner so’s to git a early supper. We eat supper a quarter past four P. M. with our things all on, and I packed up the dishes in the sink, which I seldom do, but felt that this wuz a extra occasion, and I didn’t want to wash dishes with my mantilly on, the tabs dribblin’ down into the water.

Well, to go by the crossroad leading to Zoar and turnin’ off by the Cobble Stun schoolhouse, it is only five milds to Edgewater, where Miss Greene Smythe boards for the summer. The big summer hotel there has as much as twenty acres of land round it, all full of trees and windin’ walks and summerhousen, and hammocks and swings and posy beds, and croquet grounds and baseball grounds, where they kick each other about and lame themselves and break bones, and be jest as fashionable as they can be, and have everything else for their comfort. And in front of all is the clear, blue waters of the lake, with boathousen and little boats floatin’ on the surface jest like a flock of white geese down to our pond.

As we driv onto the grounds on a broad gravel walk with brilliant posy beds on each side on’t, I see closter to the house a hull lot of men fixin’ a big tent with flags on’t and puttin’ out rows of little lanterns on strings leadin’ from one tree to another and standin’ out a hull lot of evergreen trees round the big tent and a lot of smaller ones.

The mair sort o’ pricked up its ears at the sight of so many strange things, but kep’ right along on the path like the well principled mair she is. But the colt bein’ younger and not so way-wised, and I don’t believe havin’ the good principle her Ma has, or ever will have, though Josiah sez she is likelier fur than her Ma wuz at her age. But, ’tennyrate she made a dash into the thickest of the crowd, and it wuzn’t till three waiters had been upsot, by bein’ taken in their back onexpected, that my pardner succeeded in catchin’ it. By this time the colt bein’ tangled in the line of lanterns and one foot ketched in the rope of evergreens, she stood still whinnerin’. And the waiters cussin’ and swearin’ fearful, and my pardner goin’ as fur that way as he dast with his professions and religion. He did say “dum” repeatedly, and “gracious Heavens!” and “gracious Peter!” and all these milder terms a deacon can use and not call it swearin’. And I, holdin’ the mair, some excited but keepin’ my conscientiousness pretty well, when a man come runnin’ out from the hotel that seemed to be in authority and he quickly loosed the bands of that colt, and sent the cussin’ waiters about their bizness and advanced onto me, it wuz the landlord, Mr. Grabhull, I knowed him and he knowed me, and he wuz real polite, though he looked cross as a bear, I must say.

And he asked me if I wouldn’t alight, and if he couldn’t help me.

And, thinkin’ I might as well, seein’ I had got there, I did alight and git down, but refused his help, backin’ out and gittin’ down myself with some trouble, for the steps of the democrat are high, and I always use a chair to home to step down on, but wouldn’t ask him for one if I had fell out, thinkin’ we had made him enough trouble already. But the height wuz precipitous and I felt giddy, and, when at last my feet struck solid ground I sez, instinctively, and onbeknown to myself:

“Thank Heaven, as the man said, that my feet are once more on visey versey.” And then, to let him know at once why we wuz there, I took my card of invitation out of my pocket, and sez:

“We have come to Miss Greene Smythe’s Bazar for that Heathen.”

“Oh, yes,” sez he, “and you would like to see her, wouldn’t you!”

And I sez, “Yes.” And he turned towards a more secluded corner nigh to the lake, and I ketched sight of Miss Greene Smythe settin’ in a hammock with three young men hoverin’ round her like small planets round the sun. Them Danglers I had hearn on, I felt sure from their looks, they looked sort o’ danglin’ somehow. Two of ’em wore white flannel and the other dark-blue woolen, with light-yellowish colored shues on all on ’em, kinder slips like, one on ’em had a banjo in his hand and one on ’em seemed to be singin’.

She wuz dressed in white, with a great broad hat all covered with white feathers and streamers and things, and her dress wuz white, too, and she wuz layin’ back in the hammock on some gay-colored cushions as easy as you please, and one of them Danglers had a big fan and wuz fannin’ her. But even as I looked that colt broke away from the landlord, and, bein’ skairt most to death, jest bounded into that peaceful group and scattered it like chaff before a whirlwind. She upset the feller with the banjo, steppin’ right into the fiddle as she jumped clean over the hammock, one heel kickin’ off and goin’ through that great white hat, and stepped into the stomach of the dangler who held the fan and broke off the feller’s song right in the most effective place, for he wuz jest singin’ in a deep beartone:

“Come where my love lies dreaming.”

And, as if in answer, the colt come, one foot come square down into them dreams, if she wuz dreamin’, and tore off more than five yards of lace and ribbons, whilst the other one took off the big hat, as I said, amidst her loud screams. My first thought wuz she would have a coniption fit, and even in that minute, so practical is my mind, I wondered what I should do without catnip or burnt feathers. But even as I thought this she turned towards me and see who I wuz and what had caused the fracas, for Josiah and the landlord wuz follerin’ on in hot pursuit, whilst the old mair stood in the background whinnerin’ to her colt, either in encouragement or remonstrance, I couldn’t tell which.

Miss Greene Smythe looked cross enough to eat a file at that first look, but immegiately the young men sprung up, one gathered up her laces and ribbons and placed ’em in her hands, another her fan and book, and, though I am ready to testify that that first look she gin me wuz mad as a-settin’ hen with a brindle dog round, before I could hardly git the run of that look and set it down in my mind memorandum, she put on a dretful warm smile, yet as queer lookin’ as any I ever see, and I have seen queer lookin’ smiles in my day and gin ’em, too, yes, indeed! and she come forward, holdin’ out her hand with the lace and ribbin danglin’ from it, and sez she, “How good of you to come, you will spend the day with me, won’t you?”

“Spend the day!” sez I, agast at the idee; “why, we have come to your reception and Bazar for that Heathen, but if I had knowed how that colt wuz goin’ to act we would tied it to the fills, we couldn’t leave it to home, for it hain’t weaned. I feel mortified and sorry to think it pitched into you so, and upset them Danglers,” I wuz jest a-goin’ to say, but bethought myself and sez, “them young chaps, I feel dretful sorry, and am willin’ to repair damages jest so fur as I can. I’ll give you one of my hats; and that fiddle,” sez I, “if it needs new strings I stand ready to git ’em, we have got more cats than we need round the barn, and I can furnish a dozen strings as well as not, and I’ll tell the young man so.” And I advanced towards ’em.

But she hurriedly drawed me off the other way, and sez she real warm, “How good of you, how extremely good of you to stay to the reception!” And then she sez, lookin’ round sort o’ helplessly and mournfully towards the Danglers, and then at me agin:

“You—oh!—let me see—yes—you come right up into my room, and dear Mr. Allen must come into the reading room. They have caught the colt, I see; I will rejoin you in a minute.”

And she slipped back to say a few words to them deserted Danglers, who looked as helpless and queer as planets might look when through some upheaval the sun wuz suddenly removed, and they wuz left hangin’ round in space with nothin’ to revolve round. I thought I hearn her say sunthin’ about havin’ to git a little rest, anyway; the idee I thought of anybody goin’ to bed at that time of day, and sunthin’ about seein’ ’em all to-night, and then she said she wouldn’t say good-by, but awe revoir, and they all said it to her, shakin’ hands with her and hangin’ over her hand as if they wuz goin’ to the fur Injys as missionaries liable to be eat up by savages, never to see her agin.

I spoze they referred to the “awe” they felt in seein’ a young colt like that so uncommon active, what the “revoir” meant I don’t know, unless it wuz some man by that name who owned a colt not nigh so smart as ourn. Yes, indeed, that colt well merits Josiah’s enconiums so fur as smartness is concerned. He had led Mr. Grabhull and Josiah a tegus chase, but at last, as I could see, glancin’ towards the lake, Josiah Allen had got a firm grip onto his mane and wuz leadin’ him back, still wearin’ the hat on his foreleg instead of his foretop. The hat wuz spilte.

The smartest creeters have their limitations. That colt could make light of Danglers and fashionable wimmen, step through their hats, tromple on ’em and leap over ’em, scatter ’em like leaves in a high gale, but when he come bunt up aginst the lake and whinnered at it, and it still lay calm and smooth before him and wuzn’t danted, he gin up that the lake wuz too big a job for him to tackle and subdue, so he stood quite meek and wuz ketched. Presently the cavalcade drawed nigh to us, and Miss Greene Smythe repeated her invitation that dear Mr. Allen must come right into the reading room, where he would find all the last papers.

“Is the World there?” sez Josiah, prickin’ up his ears at the idee, he wuz all tuckered out and wanted to set down and rest. “Oh, yes,” sez she, “the Weekly, the Daily, and the Sunday World. I will have a couple of waiters bring those papers to you,” sez she.

“Yes,” sez I, “they are hefty.”

Well, I see that Josiah wuz full of happiness in a quiet corner of that big readin’ room overlookin’ the lake, for there wuzn’t hardly a soul in it at that time, and his beloved papers stacked up in front of him some like a small haystack, he wuz fairly overrunnin’ with contentment. Mr. Grabhull had led the colt towards the stables, havin’ persuaded it to lay off its hat, and one of the waiters wuz leadin’ the old mair.

Then I turned and silently follered Miss Greene Smythe up to her room. Lots of men wuz to work hangin’ draperies and puttin’ flowers up on the walls, and strings of evergreens and ribbins and makin’ it dretful pretty. But Miss Greene Smythe led the way through ’em all into what she called her boodore, and there she gin me a rockin’ chair and I sot down, she asked me to lay off my things, but I told her I guessed I wouldn’t take off my bunnet, bein’ as I would have to put it on so quick, but I loosened the strings and took off my mantilly, carefully foldin’ the tabs as I did so and holdin’ it in my lap. She called a fashionably dressed girl with a cap on, who wuz to work on a pile of satin drapery when we went in, to come and take my mantilly. But I told her I jest as lives hold it in my lap, as I should want to put it on so soon.

She looked sort o’ wonderin’ and went back to her work. I see, on lookin’ closter, that it wuz a dress of pale-blue satin with a deep velvet train, and she wuz puttin’ on the waist strings of gems of all colors, and that skirt! I am tellin’ you the livin’ truth, that velvet train wuz as long as from our bedroom to the parlor door, and I d’no but it wuz as long as from our bedroom acrost the hall into the spare room, ’tennyrate it wuz the longest skirt I ever see or expect to see, all lined with pale-pink satin.

Miss Greene Smythe sez, “I am to be Queen Elizabeth in full court dress. Here is my collar,” sez she, “and my crown,” and she showed a immense collar of white lace and a crown all covered with precious stuns in flowers and figgers, it fairly glittered and shone like the posy bed in the early mornin’ when the dew is shinin’ on it.

“I have combined,” sez she, “a Bazar, a reception, and a fancy dress ball, for there will be dancing after supper is served.”

“What time is supper?” sez I, for I scented trouble ahead.

“Oh, about one,” sez she.

Sez I aghast, “Do you mean one o-clock at night?”

“Yes,” sez she.

“What time do you begin the doin’s?” sez I.

“Oh, the Bazar will be opened at ten, the reception at twelve, the dancing beginning after supper, about two o-clock.”

“For the land’s sake!” sez I; “for the land’s sake!” and I leaned back in my chair perfectly overcome by the programmy. And sez I, “What time do you end up?”

“Oh, we may be through about sunrise, but if it is later it is no matter, for the rooms will be darkened and we can dance until nine o’clock, if we choose.”

I wuz speechless with my emotions; I couldn’t quell ’em and didn’t want to, but Miss Greene Smythe didn’t notice ’em, for she seemed all took up tellin’ her maid where to put the gorgeousest of the gems she wuz sewin’ onto the satin, and then she sez sunthin’ about seein’ Medora a minute and handed me a hull lapfull of books and magazines, and sayin’ sunthin’ to the girl about refreshments, she left the room. I wuz settin’ tryin’ to read them magazines she had piled in my lap, but I didn’t git much interested in ’em, for they wuz all about fashions and boleros, which I had always thought wuz some kind of a Mexican steer, but found out it wuz sunthin’ to wear, and reveres, which sounded well, but meant fashionable clothing, and so on lots of other strange names and descriptions, but I didn’t care much for ’em.

Well, I had turned ’em over and had jest lit on sunthin’ so important that they put it even into a fashionable magazine, a long description of a football race and a college athletic contest in which two young men had got maimed for life and one killed outright, and more’n two hundred drunk as fools, and I wuz readin’ it with horrow when my companion come up crazy with a new idee, he had heard there wuz goin’ to be a fancy ball, and he wanted to join it in costoom and attend the ball.

Sez I, “Josiah Allen, I shall not stay here till twelve P. M., but, if I wuz goin’, I should go as myself, and not as anybody else.”

“Why,” sez he, “the fancy dress is goin’ to be first. We can jine in that and then go home, for I don’t want to dance,” sez he.

“I should think as much,” sez I coldly; “a deacon, and most dead with rheumatiz, to say nothin’ of the grandchildren, why,” sez I, “one pigeon wing, or one goin’ down through the middle, or all hands round, would crumple you right up and be the death of you.”

“Well, I told you explicitly that I didn’t lay out to dance, nor didn’t ask you to.”

Sez I coldly, “If you did it would be a outlay of politeness that would be throwed away. Dance!” sez I, “when I can’t git up or set down without groanin’, and my principles like iron.”

“Well, well, who said they wuzn’t? I told you we wouldn’t dance this evenin’, but,” sez he impressively, “we can dress up fancy, or I can, and swing out for once and be fashionable and gay.”

“I would like to know where you can git your things to swing out in, and what character you would represent and what dress you would go in.”

“Well,” sez he, crossin’ his legs and lookin’ real contented and happy, “I thought I would go as a child.”

“As a child!” sez I, astounded at his idee.

“Yes,” sez he, “as a babe. I have planned it all out; I could slip over to the store, this summer store they have got here to accommodate the boarders, and buy twenty yards or so of sheetin’, you could use it afterwards for sheets, you know, and you could pin it onto me and tie it round the waist with a pale-blue sash. I could buy a couple of yards of blue cambric and you could tear it into, and tie it round my waist with a big bow, and there I would be a babe.”

“What would you do with your whiskers?” sez I coldly. “And your wrinkles and your gray bald head?”

“By Jimminy!” sez he, “I forgot them.”

He see himself, as quick as his attention wuz drawed to it, that a babe in long white dresses ortn’t to have gray whiskers and a bald head.

“Well,” sez he, “what do you say to a Pirate or a Bandit chief? I could buy a piece of red and yeller creeton, figgered, and a piece of striped for a sash. They’re always depictered in dime novels as bein’ very dressy with feathers, and I could kinder jam in the top of my hat and put some feathers in it, I could buy a couple of turkey wings of Nate Enders, he deals in turkeys, and I have to go most to his house to go to the store—what do you say, Samantha? Or, would you go as a Shepherd Boy, or how would you go?”

I wuz wore out, and I sez, “I would go as a natteral fool, Josiah, and you wouldn’t have to buy anything or change a mite to do it.”

“Yes, there it is; keep right on, I never knew it to fail in my life; I never yet got a chance to enter fashionable life and show off a little but you tried to break it up.” Sez he still more pitiful, “I always wanted to look fancy, Samantha, and you’ve never seemed willin’. I don’t say that you are jealous of my looks, for I don’t think you are any such a woman, but I will say it looks queer, but now there is a chance for me to look gay, and I am goin’ to embrace it.”

Jest that minute the girl with the cap on come into the room agin, and I nudged him to keep still, but he wouldn’t. I enticed him over to the winder and argued with him there. My voice wuz real low, but he wuz so excited and spoke so loud the girl must have got a inklin’ of what he wuz sayin’, and, seein’ the dilemma I wuz in, she spoke right up and sez with her queer little axent:

“They wuz not all to appear in Fancy Dress, it wuz for the young mostly, the aged were not expected to appear in costume.”

And that madded Josiah more than ever; he duz want to appear young; he don’t grow old as graceful as I could wish, and he hollered out:

“Where are your aged folks? I don’t see any. I am in the prime of life myself, and, as for Samantha, she don’t have to wear a cap, anyway.”

“No, Moseer,” sez she, real polite, but she contended firm as iron, bein’ my friend, as I could see, that “Madam and Moseer would not be expected to appear in costoom.”

“Well, Modom can do as she is a mind to,” sez he, mocking the girl’s way of pronouncin’ Madame, and it did sound some like swearin’, but I didn’t mind, “Modom can do as she is a mind to, but I am goin’ in costoom.”

But I whispered to him and sez, “When perfect strangers warn you for your good, Josiah Allen, mebby you’ll listen to ’em if you won’t to me.” I won’t put down the words he replied to me in a savage whisper, nor his answer to my arguments, no it hain’t best, he is my pardner, and I took him for better or worse, and why should I flinch when the worst appears? No, I will pass over the time till I got him subsided in a big armchair by my side (no wonder he wuz tired) readin’ a portion of his World that he had brung up in his hand.

The girl looked feelin’ly at me as he sot there, still mutterin’ occasionally, and she went out, and a little while after a waiter appeared with a tray full of good vittles, splendid. Whether that girl is married or single, she knows men’s naters and what is the soothinest emolyent to apply to ’em. As he helped himself to the third helpin’ of nice, tender chicken with accompaniments of creamed potatoes and toast and coffee, good as I can make a most, his mean relaxed and he put on a less madder look, and as he took the fourth slice of some good cake and jelly, his axent wuz almost tender as he sez, “Well, Samantha, my dear, when had we better go down and jine the party?”

“There hain’t any party to jine now, but if you feel like it we will go down pretty soon and walk round the grounds and along the lake till the company comes, and,” sez I, “if I had mistrusted before I left home that this thing didn’t begin till after bedtime, I wouldn’t have stirred a step, and wouldn’t, anyway, if it hadn’t been for that Heathen, but sence we are here we might as well stay and see some of it, and then go home.”

“Yes,” sez he, “it won’t be no worse than watch meetin’, anyway.”

So this programmy wuz carried out by us. We walked round the grounds, by this time all alive with men and wimmen and waiters runnin’ every which way, puttin’ up lamps and lanterns and awnin’s, and fixin’ booths and seats, etc., etc., and I thought to myself how much that Heathen is havin’ done for him, and I wondered if he realized it and appreciated it as he ort to.

We walked round till we got tired and then sot down on a bench by the lake shore, and, bein’ tired, I d’no but we fell into a drowse, ’tennyrate we rested real good. The gentle swash of the waves on the pebbly beach sounded sort o’ soothin’ and refreshin’, jinin’ in as it did with the soft night wind that wuz blowin’ in from the west. Pretty soon the sun went down into the lake that looked as if we might walk away on it clear into Glory if we tried to, and then the stars come out and glistened in the clear sky overhead, and the crescent moon hung in the east like a great silver hammock for angels to lay down in and rest their wings some. And almost simeltaneous with the stars overhead come the lightin’ of a thousand lights around us, behind us, and before us, sparkling, glittering, shining lights of all shapes and colors glancin’ through the evergreen boughs and soft foliage, and hung in long lines of brilliant color from tree to tree. The hotel looked as if it wuz a sea of light inside, and the big tent looked as brilliant as Aladin’s palace, and the long line of little booths on each side looked, too, as if they had been brought from Arabia and sot down there, so strange and brilliant they looked with gorgeous curtains and tables all heaped up with beautiful objects to sell and lights sparklin’ everywhere.

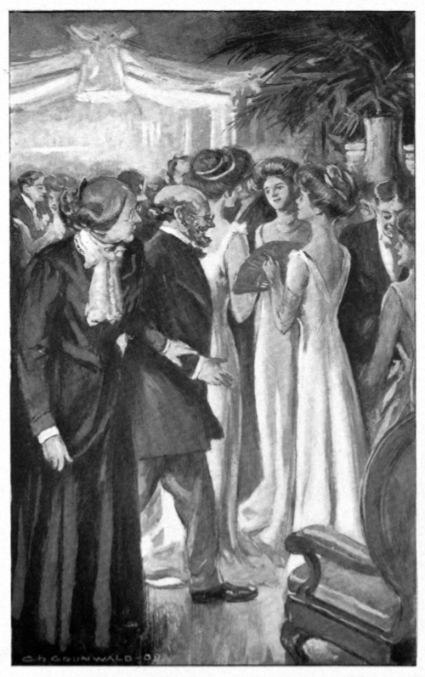

Well, by the time we got rousted up and walkin’ round and viewin’ the seen the music had struck up in a tent by itself, enchantin’ music that seemed to roust up our souls and bodies, too. Pretty girls and handsome wimmen wuz standin’ behind the tables in them little booths sellin’ their wares for the benefit of that Heathen to the brilliant crowd that wuz beginnin’ to fill the walks and tents, a brilliant crowd indeed, for every costoom of every age wuz represented.

And they wuz so beautiful, and the music wuz so soft and enchantin’, that I did wish that Heathen could have looked on that seen that wuz bein’ done for him. I believe it would have shamed him if he had any shame, and he wouldn’t eat up any more missionaries, not for some time, anyway, but then, as I told Josiah, he probable wouldn’t feel to home here and probable wuzn’t dressed decent for the occasion.

And he sez, pintin’ to a woman who wuz walkin’ round locked arms with a man and holdin’ a gold eyeglass to her eye, “I d’no but he would feel to home with her.”

And, as I looked on her, I see my pardner wuz right, her waist wuz jest a mockery of a waist, a belt and a string over her shoulder wuz about all, and her arms bare to her shoulders, only some gloves drawed on part way. I drawed him away at a good jog and walked him into what I thought wuz a place of safety, but, good land! I see I had got him into a worse place by far, for whereas there had been only one female heathen, as you may say, here wuz more than a dozen. I was so took up with the seen that I didn’t realize what wuz about us till I hearn Josiah gin a low chuckle, and I sez:

“What is the matter, Josiah Allen?”

And he sez, “Oh, nothin’.” But as I looked round I see plain what he wuz chucklin’ over, and I hurried him away. As we went, he sez:

“You no need to worried, Samantha, about that naked Heathen not feelin’ to home.”

“Well,” sez I, “they have got clothes enough on from their waist down.” I will stand up for my sect, anyway.

“Yes,” sez Josiah, “if these wimmen and girls would take some of the silk and gauzes that are straingin’ down on the ground to cover up their nakedness they would look better, enough sight.”

Sez I, “You hain’t obleeged to look on ’em.”

“Well,” sez he, real impatient, “put girl blinders on me if you want to, but I have got to look round some till you do.”

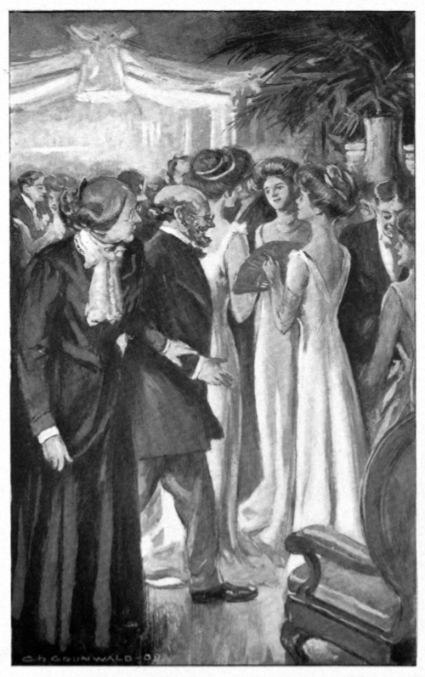

I DRAWED HIM AWAY AT A GOOD JOG, AND WALKED HIM INTO WHAT I THOUGHT WUZ A PLACE OF SAFETY.

And I sez, “We will go into the booths and trade a little.” Here he groaned pitiful, but I reminded him that the Heathen had got to be helped some by us, and he sez, “That Heathen has more done for him than I have, enough sight.”