a certain result would follow, while, if we did not, the result would not

follow. For a man may predict an event ten thousand years beforehand,

and another may predict the reverse; that which was truly predicted at the

moment in the past will of necessity take place in the fullness of time.

From the reading. . .

“For a man may predict an event ten thousand years beforehand, and

another may predict the reverse; that which was truly predicted at the

moment in the past will of necessity take place in the fullness of time.”

Further, it makes no difference whether people have or have not actu-

376

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 32. “The Sea-Fight Tomorrow” by Aristotle

ally made the contradictory statements. For it is manifest that the circum-

stances are not influenced by the fact of an affirmation or denial on the

part of anyone. For events will not take place or fail to take place because

it was stated that they would or would not take place, nor is this any more

the case if the prediction dates back ten thousand years or any other space

of time. Wherefore, if through all time the nature of things was so consti-

tuted that a prediction about an event was true, then through all time it was

necessary that that should find fulfillment; and with regard to all events,

circumstances have always been such that their occurrence is a matter of

necessity. For that of which someone has said truly that it will be, cannot

fail to take place; and of that which takes place, it was always true to say

that it would be.

[Potentiality and the Future]

Yet this view leads to an impossible conclusion; for we see that both de-

liberation and action are causative with regard to the future, and that, to

speak more generally, in those things which are not continuously actual

there is potentiality in either direction. Such things may either be or not

be; events also therefore may either take place or not take place. There are

many obvious instances of this. It is possible that this coat may be cut in

half, and yet it may not be cut in half, but wear out first. In the same way,

it is possible that it should not be cut in half; unless this were so, it would

not be possible that it should wear out first. So it is therefore with all other

events which possess this kind of potentiality. It is therefore plain that it

is not of necessity that everything is or takes place; but in some instances

there are real alternatives, in which case the affirmation is no more true

and no more false than the denial; while some exhibit a predisposition and

general tendency in one direction or the other, and yet can issue in the

opposite direction by exception.

Now that which is must needs be when it is, and that which is not must

needs not be when it is not. Yet it cannot be said without qualification that

all existence and non-existence is the outcome of necessity. For there is a

difference between saying that that which is, when it is, must needs be, and

simply saying that all that is must needs be, and similarly in the case of that

which is not. In the case, also, of two contradictory propositions this holds

good. Everything must either be or not be, whether in the present or in the

future, but it is not always possible to distinguish and state determinately

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

377

Chapter 32. “The Sea-Fight Tomorrow” by Aristotle

which of these alternatives must necessarily come about.

From the reading. . .

“It is therefore plain that it is not necessary that of an affirmation and

a denial one should be true and the other false.”

Let me illustrate. A sea-fight must either take place to-morrow or not,

but it is not necessary that it should take place to-morrow, neither is it

necessary that it should not take place, yet it is necessary that it either

should or should not take place to-morrow. Since propositions correspond

with facts, it is evident that when in future events there is a real alternative,

and a potentiality in contrary directions, the corresponding affirmation and

denial have the same character.

This is the case with regard to that which is not always existent or not

always nonexistent. One of the two propositions in such instances must

be true and the other false, but we cannot say determinately that this or

that is false, but must leave the alternative undecided. One may indeed

be more likely to be true than the other, but it cannot be either actually

true or actually false. It is therefore plain that it is not necessary that of

an affirmation and a denial one should be true and the other false. For in

the case of that which exists potentially, but not actually, the rule which

applies to that which exists actually does not hold good. The case is rather

as we have indicated.

Related Ideas

“On Prophesying Dreams” by Aristotle (http://www.classics.mit.edu/ \

aristotle/prophesying.html). Internet Classics Archive. Short reading on

the Aristotle’s analysis of the logic of dreams and future truths from MIT.

Aristotle’s Logic (http://www.plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-logic/).

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. An introduction and overview of

Aristotle’s contribution, including §12 Time and Necessity: Sea-Battle,

by Robin Smith.

378

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 32. “The Sea-Fight Tomorrow” by Aristotle

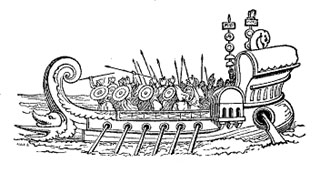

A Greek Galley, S. G. Goodrich, A History of All Nations, 1854

Topics Worth Investigating

1. Is the problem of “future truths” just another variation of the problem

of existential import? Review Immanuel Kant’s selection on “Exis-

tence Is Not a Predicate” and attempt to relate Kant’s argument to Aristotle’s statement: “For events will not take place or fail to take

place because it was stated that they would or would not take place,

nor is this any more the case if the prediction dates back ten thousand

years or any other space of time.” Are Kant’s and Aristotle’s views

compatible?

2. When Aristotle writes, “propositions whether positive or negative are

either true or false, then any given predicate must either belong to

the subject or not. . . ,” he is stating the so-called law of the excluded

middle: any proposition ( i.e. a sentence with a truth value) is either

true or false but not both. The law of the excluded middle is a founding

principle of classical logic. Investigate whether or not fuzzy logics or

multivalued logics reject this principle.

3. Study carefully the first sentence in the reading selection. Is Aristotle

presupposing that meaningful statement must be a description of an

existing subject? Explain.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

379

Chapter 32. “The Sea-Fight Tomorrow” by Aristotle

4. How is the problem of statements about the future related to the phi-

losophy of fatalism? Some people stoically say, “Whatever will be,

will be. There’s no sense in worrying about it.” Show how Aristotle’s

view, if true, would disprove such a fatalistic doctrine.

380

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 33

“What Makes a Life

Significant?” by William

James

William James, Thoemmes Press

About the author. . .

William James (1842-1910), perhaps the most prominent American

philosopher and psychologist, was an influential formulator and

spokesperson for pragmatism. Early in his life, James studied art, but

later his curiosity turned to a number of scientific fields. After graduation

from Harvard Medical College, James’ intellectual pursuits broadened

to include literary criticism, history, and philosophy. He read widely

and contributed to many different academic fields. The year following

381

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

graduation, James accompanied Louis Agassiz on an expedition to

Brazil.1 As a Harvard professor in philosophy and psychology, James

achieved recognition as one of the most outstanding writers and lecturers

of his time.

About the work. . .

In his Talks to Students,2 James presents three lectures to students—two

of them, being “The Gospel of Relaxation,” and “On a Certain Blindness

in Human Beings.” The third talk is the one presented here. His second,

“On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings,” has as its thesis that the worth

of things depends upon the feelings we have toward them. Read it online

as a companion piece to this reading at the William James Website noted

below in the section entitled “Related Ideas.”

From the reading. . .

“Every Jack sees in his own particular Jill charms and perfections to

the enchantment of which we stolid onlookers are stone-cold.”

The Selection from “What Makes Life a

Significant?”

[Life’s Values and Meanings]

IN my previous talk, “On a Certain Blindness,” I tried to make you feel

how soaked and shot-through life is with values and meanings which we

fail to realize because of our external and insensible point of view. The

meanings are there for the others, but they are not there for us. There lies

1.

See the short essay, “In the Laboratory With Agassiz,” by Samuel H. Scudder, in

Chapter 1.

2.

William James. Talks to Students. 1899.

382

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

more than a mere interest of curious speculation in understanding this. It

has the most tremendous practical importance. I wish that I could convince

you of it as I feel it myself. It is the basis of all our tolerance, social, reli-

gious, and political. The forgetting of it lies at the root of every stupid and

sanguinary mistake that rulers over subject-peoples make. The first thing

to learn in intercourse with others is non-interference with their own pecu-

liar ways of being happy, provided those ways do not assume to interfere

by violence with ours. No one has insight into all the ideals. No one should

presume to judge them off-hand. The pretension to dogmatize about them

in each other is the root of most human injustices and cruelties, and the

trait in human character most likely to make the angels weep.

Every Jack sees in his own particular Jill charms and perfections to the

enchantment of which we stolid onlookers are stone-cold. And which has

the superior view of the absolute truth, he or we? Which has the more vital

insight into the nature of Jill’s existence, as a fact? Is he in excess, being in

this matter a maniac? or are we in defect, being victims of a pathological

anæsthesia as regards Jill’s magical importance? Surely the latter; surely to

Jack are the profounder truths revealed; surely poor Jill’s palpitating little

life-throbs are among the wonders of creation, are worthy of this sympa-

thetic interest; and it is to our shame that the rest of us cannot feel like

Jack. For Jack realizes Jill concretely, and we do not. He struggles toward

a union with her inner life, divining her feelings, anticipating her desires,

understanding her limits as manfully as he can, and yet inadequately, too;

for he is also afflicted with some blindness, even here. Whilst we, dead

clods that we are, do not even seek after these things, but are contented

that that portion of eternal fact named Jill should be for us as if it were

not. Jill, who knows her inner life, knows that Jack’s way of taking it—so

importantly—is the true and serious way; and she responds to the truth

in him by taking him truly and seriously, too. May the ancient blindness

never wrap its clouds about either of them again! Where would any of us

be, were there no one willing to know us as we really are or ready to repay

us for our insight by making recognizant return? We ought, all of us, to

realize each other in this intense, pathetic, and important way.

If you say that this is absurd, and that we cannot be in love with everyone

at once, I merely point out to you that, as a matter of fact, certain persons

do exist with an enormous capacity for friendship and for taking delight

in other people’s lives; and that such persons know more of truth than if

their hearts were not so big. The vice of ordinary Jack and Jill affection is

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

383

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

not its intensity, but its exclusions and its jealousies. Leave those out, and

you see that the ideal I am holding up before you, however impracticable

to-day, yet contains nothing intrinsically absurd.

We have unquestionably a great cloud-bank of ancestral blindness weigh-

ing down upon us, only transiently riven here and there by fitful revela-

tions of the truth. It is vain to hope for this state of things to alter much.

Our inner secrets must remain for the most part impenetrable by others, for

beings as essentially practical as we are necessarily short of sight. But, if

we cannot gain much positive insight into one another, cannot we at least

use our sense of our own blindness to make us more cautious in going

over the dark places? Cannot we escape some of those hideous ancestral

intolerances; and cruelties, and positive reversals of the truth?

From the reading. . .

“. . . I merely point out to you that, as a matter of fact, certain persons do

exist with an enormous capacity for friendship and for taking delight

in other people’s lives; and that such persons know more of truth than

if their hearts were not so big. ”

For the remainder of this hour I invite you to seek with me some principle

to make our tolerance less chaotic. And, as I began my previous lecture by

a personal reminiscence, I am going to ask your indulgence for a similar

bit of egotism now.

A few summers ago I spent a happy week at the famous Assembly

Grounds on the borders of Chautauqua Lake. The moment one treads

that sacred enclosure, one feels one’s self in an atmosphere of success.

Sobriety and industry, intelligence and goodness, orderliness and ideality,

prosperity and cheerfulness, pervade the air. It is a serious and studious

picnic on a gigantic scale. Here you have a town of many thousands of

inhabitants, beautifully laid out in the forest and drained, and equipped

with means for satisfying all the necessary lower and most of the

superfluous higher wants of man. You have a first-class college in full

blast. You have magnificent music—a chorus of seven hundred voices,

with possibly the most perfect open-air auditorium in the world. You have

every sort of athletic exercise from sailing, rowing, swimming, bicycling,

to the ball-field and the more artificial doings which the gymnasium

384

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

affords. You have kindergartens and model secondary schools. You have

general religious services and special club-houses for the several sects.

You have perpetually running soda-water fountains, and daily popular

lectures by distinguished men. You have the best of company, and yet

no effort. You have no zymotic diseases, no poverty, no drunkenness,

no crime, no police. You have culture, you have kindness, you have

cheapness, you have equality, you have the best fruits of what mankind

has fought and bled and striven for under the name of civilization for

centuries. You have, in short, a foretaste of what human society might be,

were it all in the light, with no suffering and no dark corners.

I went in curiosity for a day. I stayed for a week, held spell-bound by the

charm and ease of everything, by the middle-class paradise, without a sin,

without a victim, without a blot, without a tear.

The Boat Landing, Lake Chautauqua, New York, Library of Congress

And yet what was my own astonishment, on emerging into the dark and

wicked world again, to catch myself quite unexpectedly and involuntarily

saying: “Ouf! what a relief! Now for something primordial and savage,

even though it were as bad as an Armenian massacre, to set the balance

straight again. This order is too tame, this culture too second-rate, this

goodness too uninspiring. This human drama without a villain or a pang;

this community so refined that ice-cream soda-water is the utmost offer-

ing it can make to the brute animal in man; this city simmering in the tepid

lakeside sun; this atrocious harmlessness of all things,—I cannot abide

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

385

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

with them. Let me take my chances again in the big outside worldly wilder-

ness with all its sins and sufferings. There are the heights and depths, the

precipices and the steep ideals, the gleams of the awful and the infinite;

and there is more hope and help a thousand times than in this dead level

and quintessence of every mediocrity.”

Such was the sudden right-about-face performed for me by my lawless

fancy! There had been spread before me the realization—on a small,

sample scale of course—of all the ideals for which our civilization has

been striving: security, intelligence, humanity, and order; and here

was the instinctive hostile reaction, not of the natural man, but of a

so-called cultivated man upon such a Utopia. There seemed thus to be

a self-contradiction and paradox somewhere, which I, as a professor

drawing a full salary, was in duty bound to unravel and explain, if I could.

So I meditated. And, first of all, I asked myself what the thing was that was

so lacking in this Sabbatical city, and the lack of which kept one forever

falling short of the higher sort of contentment. And I soon recognized that

it was the element that gives to the wicked outer world all its moral style,

expressiveness and picturesqueness,—the element of precipitousness, so

to call it, of strength and strenuousness, intensity and danger. What ex-

cites and interests the looker-on at life, what the romances and the statues

celebrate and the grim civic monuments remind us of, is the everlasting

battle of the powers of light with those of darkness; with heroism, reduced

to its bare chance, yet ever and anon snatching victory from the jaws of

death. But in this unspeakable Chautauqua there was no potentiality of

death in sight anywhere, and no point of the compass visible from which

danger might possibly appear. The ideal was so completely victorious al-

ready that no sign of any previous battle remained, the place just resting on

its oars. But what our human emotions seem to require is the sight of the

struggle going on. The moment the fruits are being merely eaten, things

become ignoble. Sweat and effort, human nature strained to its uttermost

and on the rack, yet getting through alive, and then turning its back on its

success to pursue another more rare and arduous still—this is the sort of

thing the presence of which inspires us, and the reality of which it seems

to be the function of all the higher forms of literature and fine art to bring

home to us and suggest. At Chautauqua there were no racks, even in the

place’s historical museum; and no sweat, except possibly the gentle mois-

ture on the brow of some lecturer, or on the sides of some player in the

ball-field.

386

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

Such absence of human nature in extremis anywhere seemed, then, a suf-

ficient explanation for Chautauqua’s flatness and lack of zest.

But was not this a paradox well calculated to fill one with dismay? It looks

indeed, thought I, as if the romantic idealists with their pessimism about

our civilization were, after all, quite right. An irremediable flatness is

coming over the world. Bourgeoisie and mediocrity, church sociables and

teachers’ conventions, are taking the place of the old heights and depths

and romantic chiaroscuro. And, to get human life in its wild intensity, we

must in future turn more and more away from the actual, and forget it, if

we can, in the romancer’s or the poet’s pages. The whole world, delightful

and sinful as it may still appear for a moment to one just escaped from

the Chautauquan enclosure, is nevertheless obeying more and more just

those ideals that are sure to make of it in the end a mere Chautauqua As-

sembly on an enormous scale. Was im Gesang soll leben muss im Leben

untergehn. Even now, in our own country, correctness, fairness, and com-

promise for every small advantage are crowding out all other qualities.

The higher heroisms and the old rare flavors are passing out of life.3

With these thoughts in my mind, I was speeding with the train toward Buf-

falo, when, near that city, the sight of a workman doing something on the

dizzy edge of a sky-scaling iron construction brought me to my senses very

suddenly. And now I perceived, by a flash of insight, that I had been steep-

ing myself in pure ancestral blindness, and looking at life with the eyes

of a remote spectator. Wishing for heroism and the spectacle of human

nature on the rack, I had never noticed the great fields of heroism lying

round about me, I had failed to see it present and alive. I could only think

of it as dead and embalmed, labelled and costumed, as it is in the pages of

romance. And yet there it was before me in the daily lives of the laboring

classes. Not in clanging fights and desperate marches only is heroism to

be looked for, but on every railway bridge and fire-proof building that is

going up to-day. On freight-trains, on the decks of vessels, in cattleyards

and mines, on lumber-rafts, among the firemen and the policemen, the de-

mand for courage is incessant; and the supply never fails. There, every day

of the year somewhere, is human nature in extremis for you. And wherever

a scythe, an axe, a pick, or a shovel is wielded, you have it sweating and

3.

This address was composed before the Cuban and Philippine wars. Such out-

bursts of the passion of mastery are, however, only episodes in a social process which

in the long run seems everywhere heading toward the Chautauquan ideals.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

387

Chapter 33. “What Makes a Life Significant?” by William James

aching and with its powers of patient endurance racked to the utmost under

the length of hours of the strain.