transitions come to us from point to point as being progressive, harmo-

nious, satisfactory. This function of agreeable leading is what we mean by

an idea’s verification. Such an account is vague and it sounds at first quite

trivial, but it has results which it will take the rest of my hour to explain.

Let me begin by reminding you of the fact that the possession of true

thoughts means everywhere the possession of invaluable instruments of

action; and that our duty to gain truth, so far from being a blank command

from out of the blue, or a “stunt” self-imposed by our intellect, can account

for itself by excellent practical reasons.

[Truth as the Useful]

The importance to human life of having true beliefs about matters of fact is

a thing too notorious. We live in a world of realities that can be infinitely

useful or infinitely harmful. Ideas that tell us which of them to expect

count as the true ideas in all this primary sphere of verification, and the

348

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

pursuit of such ideas is a primary human duty. The possession of truth, so

far from being here an end in itself, is only a preliminary means towards

other vital satisfactions. If I am lost in the woods and starved, and find

what looks like a cow-path, it is of the utmost importance that I should

think of a human habitation at the end of it, for if I do so and follow it,

I save myself. The true thought is useful here because the house which

is its object is useful. The practical value of true ideas is thus primarily

derived from the practical importance of their objects to us. Their objects

are, indeed, not important at all times. I may oil another occasion have no

use for the house; and then my idea of it, however verifiable, will be prac-

tically irrelevant, and had better remain latent. Yet since almost any object

may some day become temporarily important, the advantage of having a

general stock of extra truths, of ideas that shall be true of merely possible

situations, is obvious. We store such extra truths away in our memories,

and with the overflow we fill our books of reference. Whenever such an ex-

tra truth becomes practically relevant to one of our emergencies, it passes

from cold-storage to do work in the world, and our belief in it grows ac-

tive. You can say of it then either that “it is useful because it is true” or that

“it is true because it is useful.” Both these phrases mean exactly the same

thing, namely that here is an idea that gets fulfilled and can be verified.

True is the name for whatever idea starts the verification-process, useful is

the name for its completed function in experience. True ideas would never

have been singled out as such, would never have acquired a class-name,

least of all a name suggesting value, unless they had been useful from the

outset in this way.

From this simple cue pragmatism gets her general notion of truth as some-

thing essentially bound up with the way in which one moment in our ex-

perience may lead us towards other moments which it will be worth while

to have been led to. Primarily, and on the common-sense level, the truth

of a state of mind means this function of a leading that is worthwhile.

When a moment in our experience, of any kind whatever, inspires us with a

thought that is true, that means that sooner or later we dip by that thought’s

guidance into the particulars of experience again and make advantageous

connexion with them. This is a vague enough statement, but I beg you to

retain it, for it is essential.

Our experience meanwhile is all shot through with regularities. One bit of

it can warn us to get ready for another bit, can “Intend” or be significant of

that remoter object. The object’s advent is the significance’s verification.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

349

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

Truth, in these cases, meaning nothing but eventual verification, is man-

ifestly incompatible with waywardness on our part. Woe to him whose

beliefs play fast and loose with the order which realities follow in his ex-

perience: they will lead him nowhere or else make false connexions.

By “realities” or “object”’ here, we mean either things of common sense,

sensibly present, or else common-sense relations, such as dates, places,

distances, kinds, activities. Following our mental image of a house along

the cow-path, we actually come to see the house; we get the image’s full

verification. Such simply and fully verified leadings are certainly the orig-

inals and prototypes of the truth-process . Experience offers indeed other

forms of truth-process, but they are all conceivable as being primary veri-

fications arrested, multiplied or substituted one for another.

From the reading. . .

“Truth lives, in fact, for the most part on a credit system.”

[Unverified Truth]

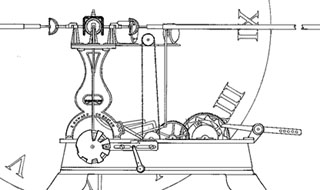

Take, for instance, yonder object on the wall. You and I consider it to

be a “clock,” altho no one of us has seen the hidden works that make it

one. We let our notion pass for true without attempting to verify. If truths

mean verification-process essentially, ought we then to call such unveri-

fied truths as this abortive? No, for they form the overwhelmingly large

number of the truths we live by. Indirect as well as direct verifications

pass muster. Where circumstantial evidence is sufficient, we can go with-

out eye-witnessing. Just as we here assume Japan to exist without ever

having been there, because it works to do so, everything we know con-

spiring with the belief, and nothing interfering, so we assume that thing to

be a clock. We use it as a clock, regulating the length of our lecture by it.

The verification of the assumption here means its leading to no frustration

or contradiction. Verifi- ability of wheels and weights and pendulum is as

good as verification. For one truth-process completed there are a million in

our lives that function in this state of nascency. They turn us towards direct

verification; lead us into the surroundings of the objects they envisage; and

350

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

then, if everything runs on harmoniously, we are so sure that verification

is possible that we omit it, and are usually justified by all that happens.

Truth lives, in fact, for the most part on a credit system. Our thoughts and

beliefs “pass,” so long as nothing challenges them, just as bank-notes pass

so long as nobody refuses them. But this all points to direct face-to-face

verifications somewhere, without which the fabric of truth collapses like a

financial system with no cash-basis whatever. You accept my verification

of one thing, I yours of another. We trade on each other’s truth. But beliefs

verified concretely by somebody are the posts of the whole superstructure.

Clock Mechanism , (detail) National Park Service

Another great reason—beside economy of time—for waiving complete

verification in the usual business of life is that all things exist in kinds and

not singly. Our world is found once for all to have that peculiarity. So that

when we have once directly verified our ideas about one specimen of a

kind, we consider ourselves free to apply them to other specimens without

verification. A mind that habitually discerns the kind of thing before it,

and acts by the law of the kind immediately, without pausing to verify,

will be a “true” mind in ninety-nine out of a hundred emergencies, proved

so by its conduct fitting everything it meets, and getting no refutation.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

351

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

Indirectly or only potentially verifying processes may thus be true as well

as full verification-processes . They work as true processes would work,

give us the same advantages, and claim our recognition for the same rea-

sons. All this on the common-sense level of matters of fact, which we are

alone considering.. . .

[Truth Is Made]

Our account of truth is an account of truths in the plural, of processes

of leading, realized in rebus , and having only this quality in common, that

they pay . They pay by guiding us into or towards some part of a system that

dips at numerous points into sense-percepts, which we may copy mentally

or not, but with which at any rate we are now in the kind of commerce

vaguely designated as verification. Truth for us is simply a collective name

for verification-processes, just as health, wealth, strength, etc. , are names

for other processes connected with life, and also pursued because it pays to

pursue them. Truth is made, just as health, wealth and strength are made ,

in the course of experience.

From the reading. . .

“The ‘absolutely’ true, meaning what no farther experience will ever

alter, is that ideal vanishing-point towards which we imagine that all

our temporary truths will some day converge. ”

Here rationalism is instantaneously up in arms against us. I can imagine a

rationalist to talk as follows:

“Truth is not made,” he will say; “it absolutely obtains, being a unique re-

lation that does not wait upon any process, but shoots straight over the head

of experience, and hits its reality every time. Our belief that yon thing on

the wall is a clock is true already, altho no one in the whole history of the

world should verify it. The bare quality of standing in that transcendent rela-

tion is what makes any thought true that possesses it, whether or not there be

verification. You pragmatists put the cart before the horse in making truth’s

being reside in verification-processes. These are merely signs of its being,

merely our lame ways of ascertaining after the fact, which of our ideas al-

ready has possessed the wondrous quality. The quality itself is timeless, like

352

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

all essences and natures. Thoughts partake of it directly, as they partake of

falsity or of irrelevancy. It can’t be analyzed away into pragmatic conse-

quences.”

The whole plausibility of this rationalist tirade is due to the fact to which

we have already paid so much attention. In our world, namely abounding

as it does in things of similar kinds and similarly associated, one verifica-

tion serves for others of its kind, and one great use of knowing things is

to be led not so much to them as to their associates, especially to human

talk about them. The quality of truth, obtaining ante rem , pragmatically

means, then, the fact that in such a world innumerable ideas work better

by their indirect or possible than by their direct and actual verification.

Truth ante rem means only verifiability, then; or else it is a case of the

stock rationalist trick of treating the name of a concrete phenomenal real-

ity as an independent prior entity, and placing it behind the reality as its

explanation. Professor Mach quotes somewhere an epigram of Lessing’s:

Sagt Hänschen Schlau zu Vetter Fritz,

"Wie kommt es, Vetter Fritzen,

Dass grad’ die Reichsten in der Welt,

Das meiste Geld besitzen?"

Hänschen Schlau here treats the principle “wealth” as something distinct

from the facts denoted by the man’s being rich. It antedates them; the facts

become only a sort of secondary coincidence with the rich man’s essential

nature.

In the case of “wealth” we all see the fallacy. We know that wealth is but a

name for concrete processes that certain men’s lives play a part in, and not

a natural excellence found in Messrs. Rockefeller and Carnegie, but not in

the rest of us.

Like wealth, health also lives in rebus . It is a name for processes, as diges-

tion, circulation, sleep, etc. , that go on happily, tho in this instance we are

more inclined to think of it as a principle and to say the man digests and

sleeps so well because he is so healthy.

With “strength” we are, I think, more rationalistic still, and decidedly in-

clined to treat it as an excellence pre-existing in the man and explanatory

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

353

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

of the herculean performances of his muscles.

With “truth” most people go over the border entirely, and treat the rational-

istic account as self-evident. But really all these words in truth are exactly

similar. Truth exists ante rem just as much and as little as the other things

do.

From the reading. . .

“‘The true,’ to put it very briefly, is only the expedient in the way of

our thinking, just as ‘the right’ is only the expedient in the way of our

behaving. ”

The scholastics, following Aristotle, made much of the distinction be-

tween habit and act. Health in actu means, among other things, good sleep-

ing and digesting. But a healthy man need not always be sleeping, or al-

ways digesting, any more than a wealthy man need be always handling

money or a strong man always lifting weights. All such qualities sink to

the status of “habits” between their times of exercise; and similarly truth

becomes a habit of certain of our ideas and beliefs in their intervals of rest

from their verifying activities. But those activities are the root of the whole

matter, and the condition of there being any habit to exist in the intervals.

[Truth as Expedience]

“The true,” to put it very briefly, is only the expedient in the way of our

thinking, just as “the right” is only the expedient in the way of our behav-

ing. Expedient in almost any fashion; and expedient in the long run and

on the whole of course; for what meets expediently all the experience in

sight won’t necessarily meet all farther experiences equally satisfactorily.

Experience, as we know, has ways of boiling over , and making us correct

our present formulas.

The “absolutely” true, meaning what no farther experience will ever alter,

is that ideal vanishing-point towards which we imagine that all our tempo-

rary truths will some day converge. It runs on all fours with the perfectly

wise man, and with the absolutely complete experience; and, if these ide-

als are ever realized, they will all be realized together. Meanwhile we have

354

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

to live to-day by what truth we can get to-day, and be ready to-morrow to

call it falsehood. Ptolemaic astronomy, euclidean space, aristotelian logic,

scholastic metaphysics, were expedient for centuries, but human experi-

ence has boiled over those limits, and we now call these things only rela-

tively true, or true within those borders of experience. “Absolutely” they

are false; for we know that those limits were casual, and might have been

transcended by past theorists just as they are by present thinkers.. . .

[Truth as Good]

Let me now say only this, that truth is one species of good , and not, as is

usually supposed, a category distinct from good, and co-ordinate with it.

The true is the name of whatever proves itself to be good in the way of be-

lief and good, too, for definite, assignable reasons. Surely you must admit

this, that if there were no good for life in true ideas, or if the knowledge of

them were positively disadvantageous and false ideas the only useful ones,

then the current notion that truth is divine and precious, and its pursuit a

duty, could never have grown up or become a dogma. In a world like that,

our duty would be to shun truth, rather. But in this world, just as certain

foods are not only agreeable to our taste, but good for our teeth, our stom-

ach and our tissues; so certain ideas are not only agreeable to think about,

or agreeable as supporting other ideas that we are fond of, but they are

also helpful in life’s practical struggles. If there be any life that it is really

better we should lead, and if there be any idea which, if believed in, would

help us to lead that life, then it would be really better for us to believe in

that idea, unless, indeed, belief in it incidentally clashed with other greater

vital benefits.

From the reading. . .

“True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and

verify. False ideas are those that we cannot. ”

“What would be better for us to believe!” This sounds very like a definition

of truth. It comes very near to saying “what we ought to believe”; and in

that definition none of you would find any oddity. Ought we ever not to

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

355

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

believe what it is better for us to believe? And can we then keep the notion

of what is better for us, and what is true for us, permanently apart?

Pragmatism says no, and I fully agree with her. Probably you also agree,

so far as the abstract statement goes, but with a suspicion that if we practi-

cally did believe everything that made for good in our own personal lives,

we should be found indulging all kinds of fancies about this world’s af-

fairs, and all kinds of sentimental superstitions about a world hereafter.

Your suspicion here is undoubtedly well founded, and it is evident that

something happens when you pass from the abstract to the concrete, that

complicates the situation.

I said just now that what is better for us to believe is true unless the belief

incidentally clashes with some other vital benefit. Now in real life what

vital benefits is any particular belief of ours most liable to clash with?

What indeed except the vital benefits yielded by other beliefs when these

prove incompatible with the first ones? In other words, the greatest enemy

of any one of our truths may be the rest of our truths. Truths have once for

all this desperate instinct of self-preservation and of desire to extinguish

whatever contradicts them.

Related Ideas

William James (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/james/). Stanford Ency-

clopedia of Philosophy : Summary content of James’ biography, writings,

and bibliography.

William James (http://www.emory.edu/EDUCATION/mfp/james.html).

Professor Frank Pajares at Emery University includes letters, essays,

reviews, texts, links, and other resources.

356

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

Harvard Medical School , (detail) NIH

Topics Worth Investigating

1. Can you identify any differences between James’ description of the

pragmatic theory of truth as represented in this reading with C. S.

Peirce’s oft-quoted statement of pragmatism? C. S. Peirce wrote:

Consider what effects which might conceivably have practical bearings

we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then our conception

of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.2

2. Discuss whether or not you think James would concur with Friedrich

Nietzsche’s famous statement on truth:

Truth is the kind of error without which a certain species of life could

not live. The value for life is ultimately decisive.3

2.

Charles Sanders Peirce. “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” in Philosophical Writ-

ings of Peirce . Ed. J. Buchler. New York: Dover, 1955.

3.

Friedrich Nietzsche. The Will to Power (1885). Trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.

J. Hollingdale. Ed. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Random House, 1967.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

357

Chapter 30. “Pragmatic Theory of Truth” by William James

3. Compare Emerson’s epistemological pragmatism as shown in the fol-

lowing quotation with James’ characterization of the “absolutely” true

as “that ideal vanishing-point towards which we imagine that all our

temporary truths will some day converge”:

We live in a system of approximations. Every end is prospective of some

other end, which is also temporary; a round and final success nowhere.

We are encamped in nature, not domesticated.4

4. James writes:

I said just now that what is better for us to believe is true unless the belief

incidentally clashes with some other vital benefit. . . . In other words, the

greatest enemy of any one of our truths may be the rest of our truths.

Discuss whether this concession to the coherence theory of truth re-

quires that pragmatism is merely the free play inherent in the practi-

cal, circumstantial application of the coherence theory of truth.

4.

Ralph Waldo Emerson. “Nature” in Essays: Second Series Boston: James

Munroe and Co., 1844.

358

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 31

“"What Is Truth?” by

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell , India Post

About the author. . .

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) excelled in almost every field of learning:

mathematics, science, history, religion, politics, education, and, of course,

philosophy. During his life, he argued for pacificism, nuclear disarmament,

and social justice. In fact he lost his teaching appointment at Trinity Col-

lege, Cambridge because of his pacificism.

An early three-volume technical work written with A. N. Whitehead

sought to prove that the fields of mathematics could be derived from

359

Chapter 31. “"What Is Truth?” by Bertrand Russell

logic. The anecdote is told by G. H. Hardy1 where Russell reported he

dreamed that Principia Mathematica , his three-volume massive study,

was being weeded out by a student assistant from library shelves two

centuries hence.

About the work. . .

In the chapter "Truth and Falsehood" in his

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Page 12 Page 13 Page 14 Page 15 Page 16 Page 17 Page 18 Page 19