PART TWO

V

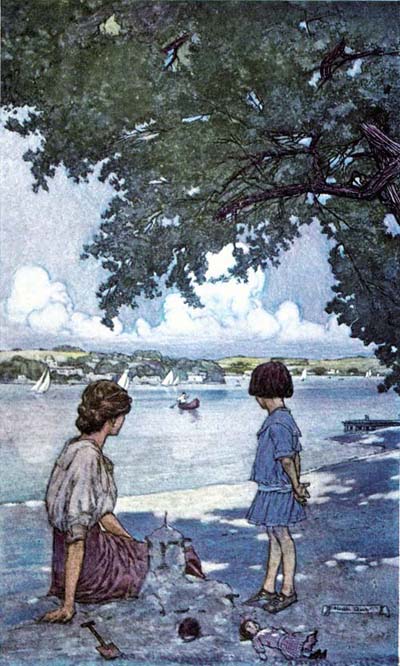

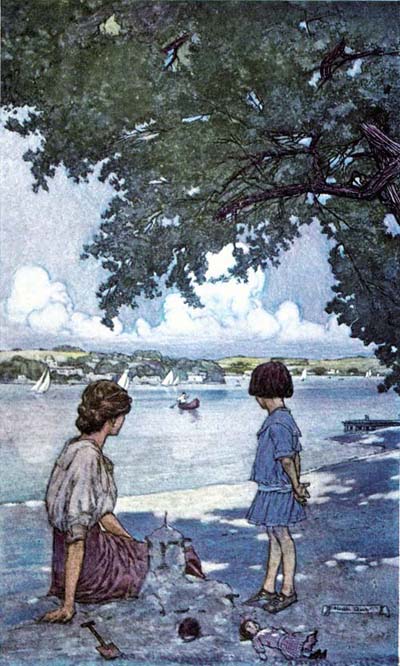

MARIAN and Marjorie had builded a house of sand on a strip of shaded beach, and by the fraudulent use of sticks and stones they had made it stand in violation of all physical laws. Now that the finishing touches had been given to the tower, Marjorie thrust her doll through a window.

“That will never do!” protested Marian. “In a noble château like this the châtelaine must not stand on her head. When the knights come riding, she must be waiting, haughty and proud, in the great hall to meet them.”

“Should ums?” asked Marjorie, watching her aunt gouge a new window in the moist wall so that the immured lady might view the lake more comfortably.

“‘Ums should,’ indeed!”

“Should the lady have coffee-cake for ums tea? We never made no pantry nor kitchen in ums house, and lady will be awful hungry. I’ll push ums a cracker. There, you lady, you can eat ums supper!”

“When her knight comes riding, he will bring a deer or maybe a big black boar and there will be feasting in the great hall this night,” said Marian.

“Maybe,” suggested Marjorie, lying flat and peering into the château, “he will kill the grand lady with ums sword; and it will be all over bluggy.”

“Horrible!” cried Marian, closing her eyes and shuddering. “Let us hope he will be a parfait, gentil knight who will be nice to the lady and tell her beautiful stories of the warriors bold he has killed for love of her.”

“My boy doll got all smashed,” said Marjorie; “and ums can’t come a-widing.”

“A truly good knight who got smashed would arrive on his shield just the same; he wouldn’t let anything keep him from coming back to his lady.”

“If ums got all killed dead, would ums come back?”

“He would; he most certainly would!” declared Marian convincingly. “And there would be a beautiful funeral, probably at night, and the other knights would march to the grave bearing torches. And they would repeat a vow to avenge his death and the slug-horn would sound and off they’d go.”

“And ums lady would be lonesome some more,” sighed Marjorie.

“Oh, that’s nothing! Ladies have to get used to being lonesome when knights go riding. They must sit at home and knit or make beautiful tapestries to show the knights when they come home.”

“Marjorie not like to be lonesome. What if Dolly est sit in the shotum—”

“Château is more elegant; though ‘shotum’ is flavorsome and colorful. Come to think of it ‘shotum’ is just as good. Dolly must sit and keep sitting. She couldn’t go out to look for her knight without committing a grave social error.”

These matters having been disposed of, Marjorie thought a stable should be built for the knights’ horses, and they began scooping sand to that end. Marian’s eyes rested dreamily upon distant prospects. The cool airs of early morning were still stirring, and here and there a white sail floated lazily on the blue water. The sandy beach lay only a short distance from Mrs. Waring’s house, whose red roof was visible through a cincture of maples on the bluff above.

“If knights comes widing to our shotum and holler for ums shootolain, would you holler to come in?” asked Marjorie, from the stable wall.

“It would be highly improper for a châtelaine to ‘holler’; but if I were there, I should order the drawbridge to be lowered, and I should bid my knight lift the lid of the coal-bucket thing they always wear on their heads,—you know how they look in the picture books,—and then ask him what tidings he brought. You always ask for tidings.”

“Does ums? Me would ask ums for candy, and new hats with long fithery feathers; and ums—”

“Hail, ladies of the Lake! May a lone harper descend and graciously vouchsafe a song?”

From the top of the willow-lined bluff behind them came a voice with startling abruptness. In their discussion of the proprieties of château life they had forgotten the rest of the world, and it was disconcerting thus to be greeted from the unknown.

“Is it ums knight come walking?” whispered Marjorie, glancing round guardedly.

Marian jumped up and surveyed the overhanging willow screen intently. She discerned through the shrubbery a figure in gray, supported by a tightly sheathed umbrella. A narrow-brimmed straw hat and a pair of twinkling eye-glasses attached to the most familiar countenance in the Commonwealth now contributed to a partial portrait of the lone harper. Marian, having heard from her sister and Mrs. Waring of the Poet’s advent, was able to view this apparition without surprise.

“Come down, O harper, and gladden us with song!” she called.

“I have far to go ere the day end; but I bring writings for one whom men call fair.”

He tossed a long envelope toward them; the breeze caught and held it, then dropped it close to the château. Marjorie ran to pick it up.

“Miss Agnew,” said the Poet, lifting his hat, “a young gentleman will pass this way shortly; I believe him to be a person of merit. He will come overseas from a far country, and answer promptly to the name of Frederick. Consider that you have been properly introduced by the contents of yonder packet and bid him welcome in my name.”

“Ums a cwazy man,” Marjorie announced in disgust. “Ums the man what told a funny story at Auntie Waring’s party and then runned off.”

The quivering of the willows already marked the Poet’s passing. He had crossed the lake to the Waring cottage, Marian surmised, and was now returning thither.

Marjorie, uninterested in letters, which, she had observed, frequently made people cry, attacked with renewed zeal the problem of housing the knights’ horses, while Marian opened the long envelope and drew out half a dozen blue onion-skin letter-sheets and settled herself to read. She read first with pleasurable surprise and then with bewilderment. Poetry, she had heard somewhere, should be read out of doors, and clearly these verses were of that order; and quite as unmistakably this, of all the nooks and corners in the world, was the proper spot in which to make the acquaintance of these particular verses. Indeed, it seemed possible, by a lifting of the eyes, to verify the impressions they recorded,—the blue arch, the gnarled boughs of the beeches, the overhanging sycamores, the distant daisy-starred pastures running down to meet the clear water. Such items as these were readily intelligible; but she found dancing through all the verses a figure that under various endearing names was the dea ex machina of every scene; and this seemed irreconcilable with the backgrounds afforded by the immediate landscape. Pomona had, it appeared, at some time inspected the apple harvest in this neighborhood:—

The dew flashed from her sandals gold

As down the orchard aisles she sped;—

or this same delightful divinity became Diana, her arrows cast aside, smashing a tennis ball, or once again paddling a canoe through wind-ruffled water into the flames of a dying September sun. Or, the bright doors of dawn swinging wide, down the steps tripped this same incredible young person taunting the waiting hours for their delay. Was it possible that her own early morning dives from Mrs. Waring’s dock could have suggested this!

Marian read hurriedly; then settled herself for the more deliberate perusal that these pictorial stanzas demanded. It was with a feeling of unreality that she envisaged every point the slight, graceful verses described. Where was there another orchard that stole down to a lake’s edge; or where could Atalanta ever have indulged herself at tennis to the applause of rapping woodpeckers if not in the court by the casino on the other side of the lake? The Poet—that is, the Poet All the People Loved—was not greatly given to the invoking of gods and goddesses; and this was not his stroke—unless he were playing some practical joke, which, to be sure, was quite possible. But she felt herself in contact with someone very different from the Poet; with quite another poet who sped Pomona down orchard aisles catching at the weighted boughs for the joy of hearing the thump of falling apples, and turning with a laugh to glance at the shower of ruddy fruit. A lively young person, this Pomona; a spirited and agile being, half-real, half-mythical. A series of quatrains, under the caption “In September,” described the many-named goddess as the unknown poet had observed her in her canoe at night:—

I watched afar her steady blade

Flash in the path the moon had made,

And saw the stars on silvery ripples

Shine clear and dance and faint and fade.

Then through the windless night I heard

Her song float toward me, dim and blurred;

’Twas like a call to vanished summers

From a lost, summer-seeking bird.

There were many canoes on Waupegan; without turning her head she counted a dozen flashing paddles. And there were many girls who played capital tennis, or who were quite capable of sprinting gracefully down the aisles of fruitful orchards. She had remained at the lake late the previous year, and had perhaps shaken apple boughs when in flight through orchards; and she had played tennis diligently and had paddled her canoe on many September nights through the moon’s path and over quivering submerged stars; and yet it was inconceivable that her performances had attracted the attention of any one capable of transferring them to rhyme. It would be pleasant, though, to be the subject of verses like these! Once, during her college days, she had moved a young gentleman to song, but the amatory verses she had evoked from his lyre had been pitiful stuff that had offended her critical sense. These blue sheets bore a very different message—delicate and fanciful, with a nice restraint under their buoyancy.

While the Poet had said that the author of the verses would arrive shortly, she had taken this as an expression of the make-believe in which he constantly indulged in his writings; but one of the canoes she had been idly observing now bore unmistakably toward the cove.

Marjorie called for assistance and Marian thrust the blue sheets into her belt and busied herself with perplexing architectural problems. Marjorie’s attention was distracted a moment later by the approaching canoe.

“Aunt Marian!” she chirruped, pointing with a sand-encrusted finger, “more foolish mans coming with glad tidings. Ums should come by horses, not by ums canoe.”

“We mustn’t be too particular how ums come, Marjorie,” replied Marian glancing up with feigned carelessness. “It’s the knights’ privilege to come as they will. Many a maiden sits waiting just as we are and no knight ever comes.”

“When ums comes they might knock down our house—maybe?” She tacked on the query with so quaint a turn that Marian laughed.

“We mustn’t grow realistic! We must pretend it’s play, and keep pretending that they will be kind and considerate gentlemen.”

Her own efforts to pretend that they were building a stable for the steeds of Arthur’s knights did not conceal her curiosity as to a young man who had driven his craft very close inshore, and now, after a moment’s scrutiny of the cove, chose a spot for landing and sent the canoe with a whish up the sandy beach half out of the water.

He jumped out and begged their pardon as Marjorie planted herself defensively before the castle.

“Ums can go ’way! Ums didn’t come widing on ums horse like my story book.”

“I apologize! Not being Neptune I couldn’t ride my horse through the water. And besides I’m merely obeying orders. I was told to appear here at ten o’clock, sharp, by a gentleman I paddled over from the village and left on Mrs. Waring’s dock an hour ago. He gave me every assurance that I should be received hospitably, but if I’m intruding I shall proceed farther upon the wine-dark sea.”

THE APPROACHING CANOE

“Is ums name Fwedwick?” asked Marjorie.

Fulton controlled with difficulty an impulse to laugh at the child’s curious twist of his name, but admitted gravely that such, indeed, was the case.

“Then ums can stay,” said Marjorie in a tone of resignation, and returned to her building.

Marian, who, during his colloquy with Marjorie, had risen and was brushing the sand from her skirt, now spoke for the first time.

“It’s hardly possible you’re looking for me—I’m Miss Agnew.”

He bowed profoundly.

“A distinguished man of letters assured me that I should find him here,” the young man explained as he drew on a blue serge coat he had thrown out of the canoe; “but unless he is hiding in the bushes he has played me false. Such being the case I can’t do less than offer to withdraw if my presence is annoying.”

The faint mockery of these sentences was relieved by the mischievous twinkle in his eyes. They were very dark eyes, and his hair was intensely black and brushed back from his forehead smoothly. His face was dark even to swarthiness and his cheek bones were high and a trifle prominent.

He was dressed for the open: white ducks, canvas shoes, and a flannel shirt with soft collar and a scarlet tie.

In spite of his offer to withdraw if his presence proved ungrateful to the established tenants of the cove, it occurred to Marian that he was not, apparently, expecting to be rebuffed. Marjorie, satisfied that the stranger in no way menaced her peace, was addressing herself with new energy to the refashioning of the stable walls along lines recommended by Marian.

“The ways of the Poet are inscrutable,” observed Fulton; “he told me your name and spoke in the highest terms of your kindness of heart and tolerance of stupidity.”

“He was more sparing of facts in warning me of your approach. He said your name would be Frederick, as though the birds would supply the rest of it.”

“Very likely that’s the way of the illustrious—to assume that we are all as famous as themselves; highly flattering, but calculated to deceive. As the birds don’t know me, I will say that my surname is Fulton. A poor and an ill-favored thing, but mine own.”

“It quite suffices,” replied Marian in his own key. “We have built a château,” she explained, “and the châtelaine is even now gazing sadly upon the waters hoping that her true knight will appear. We have mixed metaphor and history most unforgivably—a French château, set here on an American lake in readiness for the Knights of the Round Table.”

“We mustn’t quibble over details in such matters; it’s the spirit of the thing that counts. I can see that Marjorie isn’t troubled by anachronisms.”

The blue sheets containing, presumably, this young man’s verses, were still in her belt, and their presence there did not add to her comfort. Of course he might not be the real author of those tributes to the lake’s divinities. His appearance did not strongly support the suspicion. The young man who had sent her flowers accompanied by verses on various occasions was an anæmic young person who would never have entrusted himself to so tricksy a bark as a canoe. Frederick Fulton was of a more heroic mould; she thought it quite likely that he could shoulder his canoe and march off with it if it pleased him to do so. He looked capable of doing many things besides scribbling verses. His manner, as she analyzed it, left nothing to be desired. While he was enjoying this encounter to the full, as his ready smile assured her, he did not presume upon her tolerance, but seemed satisfied to let her prescribe the terms of their acquaintance. This was a lark of some kind, and whether he had connived at the meeting, or whether he was as much in the dark as she as to the Poet’s purpose in bringing them together, remained a mystery.

She found a seat on a log near the engrossed Marjorie, and Fulton settled himself comfortably on the sand.

“This has been a day of strange meetings,” he began. “I really had no intention of coming to Waupegan; and I was astonished to find our friend the Poet on the hotel veranda this morning. He had told me to come;—it was rather odd—”

“Oh, he told you to come!”

“In town, two days ago he suggested it. I wonder if he’s in the habit of doing that sort of thing.”

“It would hardly be polite for me to criticize him now that he has introduced us. I fear we shall have to make the best of it!”

“Oh, I wasn’t thinking of it in that way!”

They regarded each other with searching inquiry and then laughed. Her possession of the verses had already advertised itself to him; she saw his eyes rest upon them carelessly for an instant and then he disregarded them; and this pleased her. If he were their author—if, possibly, he had written them of her—she approved of his good breeding in ignoring them.

“I know this part of the world better than almost any other,” he went on, clasping his hands over his knees. “I was born only ten miles from here on a farm; and I fished here a lot when I was a boy.”

“But, of course, you’ve escaped from the farm into the larger world or the Poet wouldn’t know you.”

“Well, you see, I’m a newspaper reporter down at the capital and reporters know everybody.”

“Oh, the Poet doesn’t know everybody; though everybody knows him. Perhaps we’d better pass that. Tell me some more about your early adventures on the lake.”

“You have heard all that’s worth telling. We farm boys used to come over and fish before the city men filched all the bass and left only sunfish and suckers. Then I grew up and went to the State Agricultural School—to fit me for a literary career!—and I didn’t get here again until last fall when my paper gave me a vacation and I spent a fortnight at the farm and used to ride over here on my bicycle every morning to watch the summer resorters and read books.”

“It’s strange I never saw you,” said Marian, “for I was here last fall. My own memories of the pioneers go back almost to the Indians. My father used to own that red-roofed cottage you see across the lake; and I’ve tumbled into the water from every point in sight.”

“September and June are the best months here, I think. It was all much nicer, though, before the place became so popular.”

“Hardly a gracious remark, seeing that Marjorie and I are here, and all these cottagers are friends of ours!”

“I haven’t the slightest objection to you and Marjorie. You fit into the landscape delightfully—give it tone and color; but I was thinking of the noisy people at the inns down by the village. They seem rather unnecessary. The Poet and I agreed about that this morning while we were looking for a quiet place for an after-breakfast smoke.”

“It must be quite fine to know him—really know him,” she said musingly.

“Yes; but before you grow too envious of my acquaintance I’ll have to confess that I’ve known him less than a week.”

“A great deal can happen in a week,” she remarked absently.

“A great deal has!” he returned quickly.

This seemed to be rather leading; but a cry for help from Marjorie provided a diversion.

Fulton jumped up and ran to the perplexed builder’s aid, neatly repaired a broken wall, and when he had received the child’s grave thanks reseated himself at Marian’s feet. The blue onion-skin paper had disappeared from her belt; he caught her in the act of crumpling the sheets into her sleeve.

With their disappearance she felt her courage returning. His confessions as to the farm, the university, the newspaper—created an outline which she meant to encourage him to fill in. Journalism, like war and the labors of those who go down to the sea in ships, suggests romance; and Marian had never known a reporter before.

“I should think it would be great fun working on a newspaper, and knowing things before they happen.”

“And things that never happen!”

She was quick to seize upon this.

“The imagination must enter into all writing—even facts, history. Bryant was a newspaper man, and he wrote poetry, but I heard in school that he was a very good editor, too.”

“I’m not an editor and nobody has called me a poet; but the suggestion pleases me,” he said.

“If our own Poet offered you a leaf of his laurel, that would help establish your claims,—set you up in business, so to speak.”

“I should hasten to return it before it withered! My little experiments in rhyme are not of the wreath-winning kind.”

“Then you do write verses!”

“Yards!” he confessed shamelessly.

She was taken aback by this bold admission. His tone and manner implied that he set no great store by his performances, and this piqued her. It seemed like a commentary on her critical judgment which had found them good. Fulton now became impersonal and philosophical.

“It’s a great thing to have done what our Poet has done—give to the purely local a touch that makes it universal. That’s what art does when it has heart behind it, and there’s the value of provincial literature. Hundreds of men had seen just what he saw,—the same variety of types and individuals against this Western landscape,—but it was left for him to set them forth with just the right stroke. And he has done other things, too, besides the genre studies that make him our own particular Burns; he has sung of days like this when hope rises high, and sung of them beautifully; and he has preached countless little sermons of cheer and contentment and aspiration. And he’s the first poet who ever really understood children—wrote not merely of them but to them. He’s the poet of a thousand scrapbooks! I came up on a late train last night and got to talking to a stranger who told me he was on his way to visit his old home; pulled one of the Poet’s songs of June out of his pocket and asked me to read it; said he’d cut it out of a newspaper that had come to him wrapped round a pair of shoes in some forsaken village in Texas, and that it had made him homesick for a sight of the farm where he was born. The old fellow grew tearful about it, and almost wrung a sob out of me. He was carrying that clipping pinned to his railway ticket—in a way it was his ticket home.”

“Of course our Poet has the power to move people like that,” murmured Marian. “It’s genius, a gift of the gods.”

“He’s been able to do it without ever cheapening himself; there’s never any suggestion of that mawkishness we hear in vaudeville songs that implore us to write home to mother to-night! He takes the simplest theme and makes literature of it.”

Marian was thinking of her talk with the Poet at Mrs. Waring’s garden-party. Strange to say, it seemed more difficult to express her disdain of romance and poetry to this young man than it had been to the Poet. And yet he evidently accepted unquestioningly the Poet’s philosophy of life, which she had dismissed contemptuously, and in which, she assured herself, she did not believe to-day any more than she did a week ago. The incident of a pilgrim from Texas with a poem attached to his railway ticket had its touch of sentiment and pathos, but it did not weigh heavily against the testimony of experience which had proved in her own observation that life is perplexing and difficult, and that poetry and romance are only a lure and mesh to delude and betray the trustful.

“Poets have a good deal to fight against these days,” she said, wishing to state her dissent as kindly as possible. “The Bible is full of poetry, but it has lost its hold on the people; it’s like an outworn sun that no longer lights and warms the world. I wish it weren’t so; but unfortunately we’re all pretty helpless when it comes to the iron hoofs of the Time-Spirit.”

“Oh!” he exclaimed, sitting erect, “we mustn’t make the mistake of thinking the Time-Spirit a new invention. We’re lucky to live in the twentieth century when it goes on rubber heels;—when people are living poetry more and talking about it less. Why, the spirit of the Bible has just gone to work! I was writing an account of a new summer camp for children the day before I came up—one of those Sunday supplement pieces around a lot of pictures; and it occurred to me as I watched youngsters, who had never seen green grass before, having the time of their lives, that such philanthropies didn’t exist in the good old days when people dusted their Bibles oftener than they do now. There’s a difference between the Bible as a fetish and as a working plan for daily use. Preaching isn’t left to the men who stand up in pulpits in black coats on Sundays; there’s preaching in all the magazines and newspapers all the time. For example, my paper raises money every summer to send children into the country; and then starts another fund to buy them Christmas presents. The apostles themselves didn’t do much better than that!”

“Of course there are many agencies and a great deal of generosity,” replied Marian colorlessly. The young men she knew were not in the habit of speaking of the Bible or of religion in this fashion. Religion had never made any strong appeal to her and she had dabbled in philanthropy fitfully without enthusiasm. Fulton’s direct speech made some response necessary and she tried to reply with an equally frank confidence.

“I suppose I’m a sort of heathen; I don’t know what a pantheist is, but I think I must be one.”

“Oh, you can be a pantheist without being a heathen! There’s a natural religion that we all subscribe to, whether we’re conscious of it or not. There’s no use bothering about definitions or quarreling with anybody’s church or creed. We’re getting beyond that; it’s the thing we make of ourselves that counts; and when it comes to the matter of worship, I suppose every one who looks up at a blue sky like that, and knows it to be good, is performing a sort of ritual and saying a prayer.”

There was nothing in the breezy, exultant verses she had thrust into her sleeve to prepare her for such statements as these. While he spoke simply and half-smilingly, as though to minimize the seriousness of his statements, his utterances had an undeniable ring of sincerity. He was provokingly at ease—this dark young gentleman who had been cast by the waters upon this tranquil beach. He was not at all like young men who called upon her and made themselves agreeable by talking of the theater or country club dances or the best places to spend vacations. She could not recall that any one had ever spoken to her before of man’s aspirations in the terms employed by this newspaper reporter.

Marjorie, having prepared for the stabling of all the king’s horses and all the king’s men, announced her intention of contributing a wing to the château. This called for a conference in which they all participated. Then, when the addition had been planned in all soberness and the child had resumed her labors, Marian and Fred stared at the lake until the silence became oppressive. Marian spoke first, tossing the ball of conversation into a new direction.

“You have confessed to yards of verses,” she began, gathering up a handful of sand which she let slip through her fingers lingeringly, catching the grains in her palm. “I’ve seen—about a yard of them.”

Clearly flirtation was not one of his accomplishments. His “Oh, I’ve scattered them round rather freely,” ignored a chance to declare gracefully that she had been the inspiration of those lyrics, written in a perfectly legible hand on onion-skin letter-sheets, that were concealed in her sleeve. His indifference to the opening she had made for him piqued her. She was quite dashed by the calm tone in which he added, with no hint of sidling or simpering:—

“I’ve written reams of poems about you.” (He might as well have said that he had scraped the ice off her sidewalk or carried coal into her cellar, for all the thrill she derived from his admission.) “I hope you won’t be displeased; but when I was ranging the lake last September we seemed to find the same haunts and to be interested in the same sort of thing, and it kept me busy dodging you, I can tell you! I exhausted the Classical Dictionary finding names for you; and it wasn’t any trouble at all to make verses about you. I was really astonished to find how necessary you were to the completion of my pen-and-ink sketches of all this,”—a wave of the arm placed the lake shores in evidence,—“I liked you best in action; when the spirit moved you to run or drive your canoe over the water. You do all the outdoor things as though you had never done anything else; it’s a joy to watch you! I was sitting on a fence one day over there in Mrs. Waring’s orchard and you ran by,—so near that I could hear the swish of your skirts,—and you made a high jump for a bough and shook down the apples and ran off laughing like a boy afraid of being caught. I pulled out my notebook and scribbled seven stanzas on that little incident.”

Any admiration that was conveyed by these frankly uttered sentences was of the most impersonal sort conceivable. She was not used to being treated in this fashion. Even his manner of asking her pardon for his temerariousness in apostrophizing her in his verses had lacked, in her critical appraisement of it, the humility a self-respecting young woman had a right to demand of a young poet who observes her without warrant, is pleased to admire her athletic prowess, her ways and her manners, and puts her into his verses as coolly as he might pick a flower from the wayside and wear it in his coat.

“Then you used me merely to give human interest to your poems; any girl running through Mrs. Waring’s orchard and snatching at the apples would have done just as well?”

“Oh, I shouldn’t say that,” he replied, unabashed; “but even the poorest worm of a scribbler