ECONOMICS

South Africans among the most heavily taxed people in the world

Staff Writer

February 21, 2017

Finance minister Pravin Gordhan is under pressure to find an extra R28 billion in tax revenue – which is likely to come out of the pockets of South Africans who are already among the most heavily taxed people in the world.

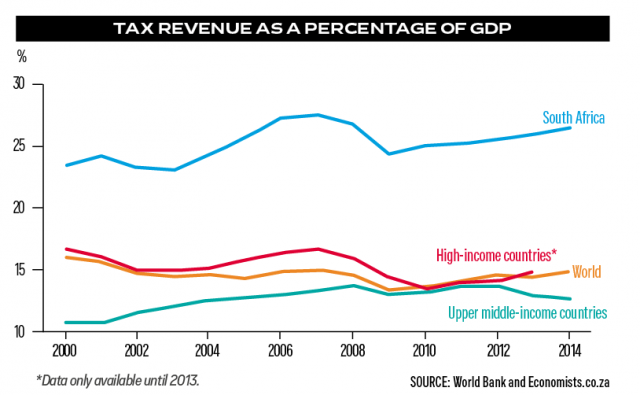

In a column written for Finweek, economist Mike Schussler provided data showing that South Africans are some of the most taxed individuals in the world – sitting well within the top 20, and climbing every year.

According to Schussler, there is a great deal of ‘spin’ involved every year when the budget speech is delivered, focusing on the more positive ‘tax relief’ delivered by government, with little fanfare around the real metrics – how much tax we are paying relative to GDP.

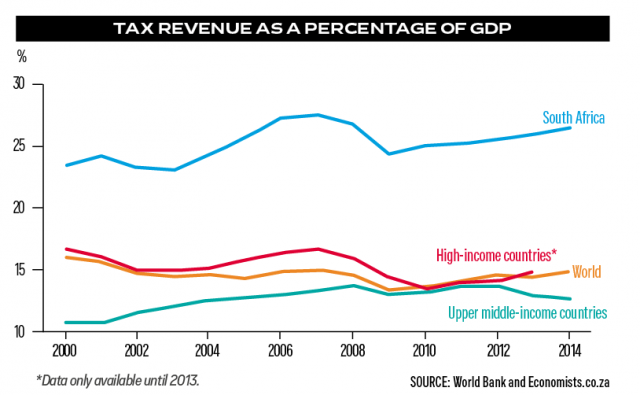

In fact, Schussler said, South Africa’s tax expressed as a percentage of GDP collected is far higher than the global, high income country and the upper-middle income country averages.

“SA has one of the highest overall tax-to-GDP ratios in the world today. World Bank data shows SA is also part of the world’s highest regional tax area,” the economist noted.

“We have been in the top 20 highest tax-to-GDP countries for about a decade now and were always in the top quarter. Now the tax burden is being raised by new taxes such as carbon and sugar taxes.”

Worse still, very little comes of it, Schussler said.

“South Africans get little value for the high tax burden if one compares education and health outcomes across countries. Very large class sizes and too few doctors given the size of the population are just two examples, while our public service wage bill is the fourth highest in the world,” he said.

The situation leads to spiral of decline: “Companies and people who add value do not want to give up so much for so little in return, so the investment dries up as taxes increase, and employment growth suffers, and more people want services.”

More tax = more money to waste

Finance minister Pravin Gordhan is faced with the challenge of covering a R28 billion tax shortfall, with few options on where to turn to get it. The most likely avenues for revenue have been identified in a jump in the fuel levy, heavier sin tax, or other taxes on the wealthy.

DA shadow minister of finance David Maynier and DA MP Alf Lees have suggested that National Treasury should focus on reeling in corruption and wasteful spending before taxing an already heavily taxed nation.

Irregular expenditure in South Africa ballooned to R46.3 billion in the 2015/16 financial year, not including the fruitless and wasteful expenditure added another R1.37 billion to the total.

Despite Gordhan’s previous declarations on government spending, ministers and other public officials have continued to spend millions of rands on luxury vehicles, hotels stays and ‘business trips’, while investigations are uncovering years and years of tender abuse, get-rich schemes, and widespread corruption have been sucking the country dry.

Academics and analysts have suggested that president Jacob Zuma and government in general be supportive of Gordhan’s bid to reel in government spending. To the contrary, however, speculation is rife that Gordhan is the cross-hairs to be booted out of Treasury and replaced with former Eskom head, Brian Molefe.

Pro-Zuma factions within the ruling party have openly criticized and called for Gordhan to be removed from the finance portfolio for impeding “transformation goals”.

The National Treasury under Gordhan has blocked a number of high-cost government programmes, including the R500 billion nuclear build, as well as multi-billion rand government bailouts for state-owned companies.

SA’s woes in four charts as embattled Zuma open Parliament

Ahead of the president’s state of the nation address on Thursday night, four gloomy graphics tell the real story of the country’s economic decline

AM Arabile Gumede

09 February 2017

President Jacob Zuma will need to confront more than opposition lawmakers disrupting his annual state of the nation address (Sona) at the opening of Parliament as he seeks to reassure the nation the economy has turned a corner.

Zuma, who has survived five bids by opposition legislators to force him from office since he took the job in 2009, is scheduled to address the National Assembly at 7pm in Cape Town on Thursday. He has ordered the army to be deployed to "maintain law and order" for the opening of Parliament; the EFF is expected to obstruct proceedings, as its members did in 2016.

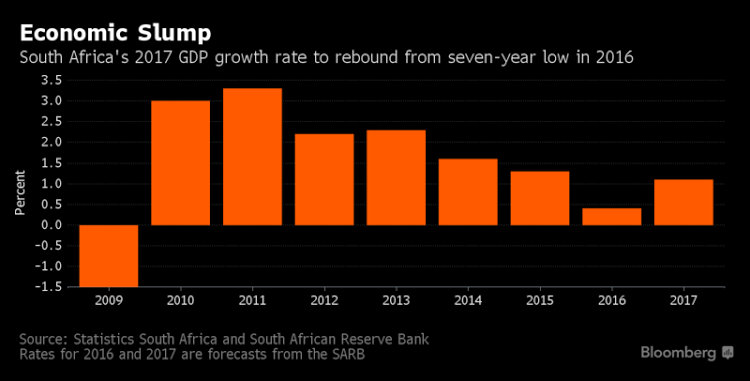

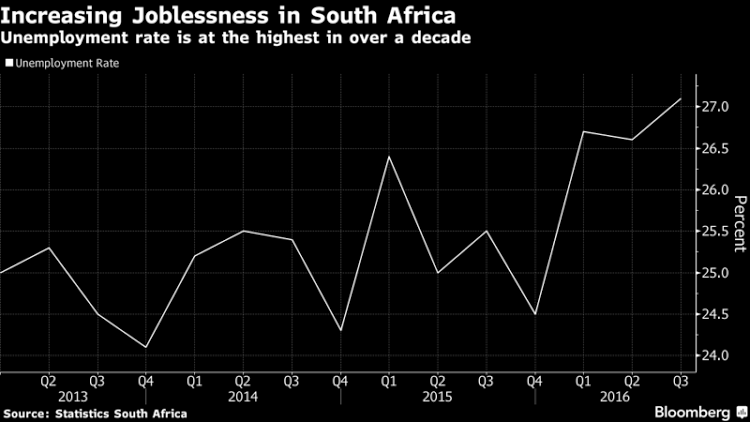

The address comes at a time when unemployment is at the highest in 13 years, economic growth last year was the slowest since a recession in 2009, and the country is struggling to retain its investment-grade credit rating.

These four charts show the economic challenges the nation faces as Zuma addresses lawmakers:

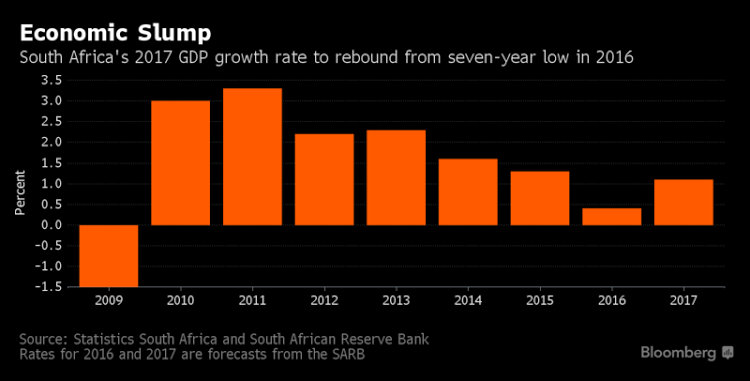

Economic growth slowed to about 0.4% last year, according to central bank estimates. This was due to a drought, weak demand from the nation’s main export partners, and low commodity prices. Political infighting in Africa’s most-industrialized economy, including a police investigation into Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, has also cast a shadow over the state’s efforts to boost confidence and growth.

While the Reserve Bank said on January 24 that the rate of expansion will probably accelerate to 1.1% this year, political uncertainty remains a risk to the economy, said Iraj Abedian, CEO at Pan-African Investments and Research Services in Johannesburg.

"Zuma is at the centre of it," Abedian said on February 7. "Growth at the moment is primarily affected by the fear of political meltdown and an open battle between him and the finance minister."

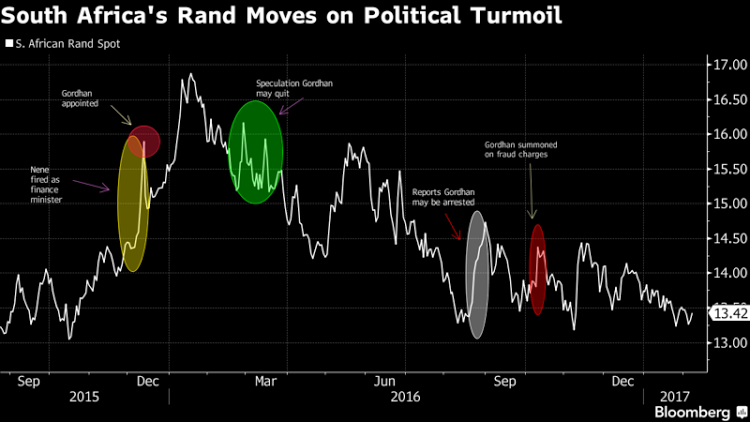

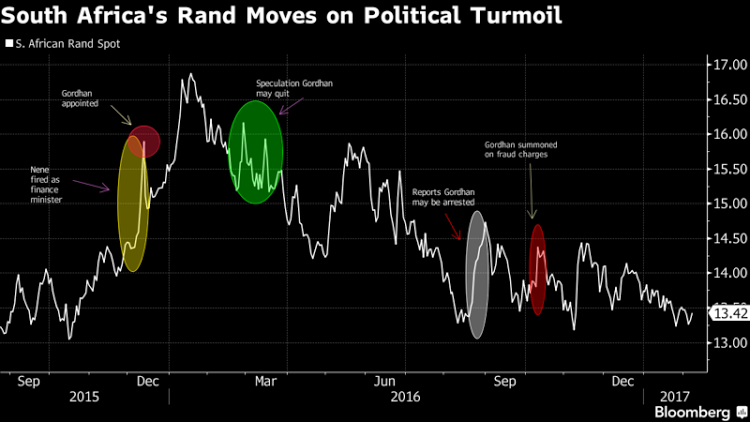

SA’s rand moves on political turmoil.

Zuma and Gordhan, who will present his budget on February 22, have been at loggerheads since his reappointment to the Treasury in 2015, disagreeing about how the tax-collection agency is managed and over Zuma’s nuclear-power expansion plans, which Gordhan says the country may not be able to afford. This, and a police investigation into Gordhan for allegedly overseeing the setting up of a spy unit at the SA Revenue Services during his time as its commissioner, hurt the rand. The local currency plunged more than 3% against the dollar on the day Gordhan was summoned to appear in court on fraud charges.

"It’s a bit of tug of war at the moment, because the rand’s fundamentals are looking quite positive, but you do have political risk," Russell Lamberti, a chief strategist at ETM Investment Services in Cape Town, said. "There is risk that the rand falls off with some bad political decision, but I think those will be short-lived."

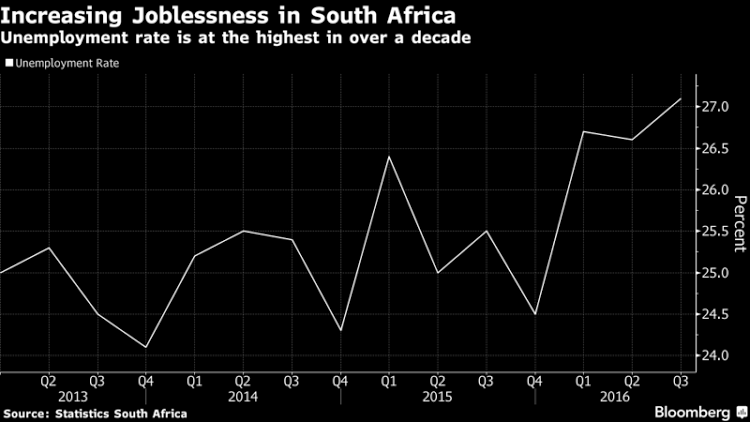

Increasing joblessness in SA.

Unemployment in SA increased to 27.1% in the quarter until September, the highest since 2003, according to data from the International Monetary Fund. According to statistics agency data, 38% of people between 15 and 34 are unemployed. This highlights the economy’s skills shortage, while poverty levels and anger over rising tuition costs have led to violent protests by students.

"There is very little that inspires businesses to hire in the current economy and the lack of policy stability is not helping either," Azar Jammine, chief economist at Econometrix in Johannesburg, said.

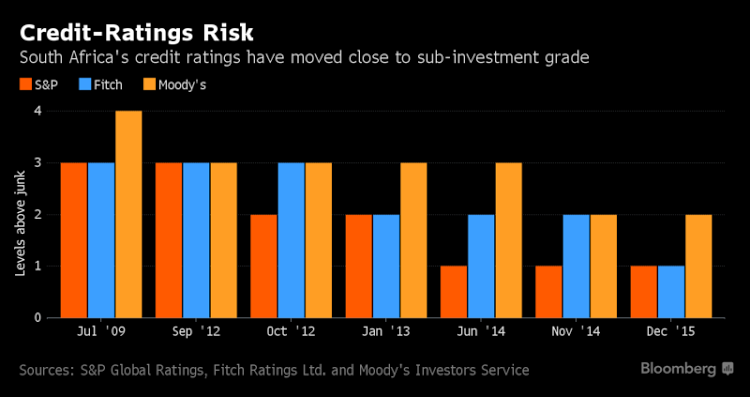

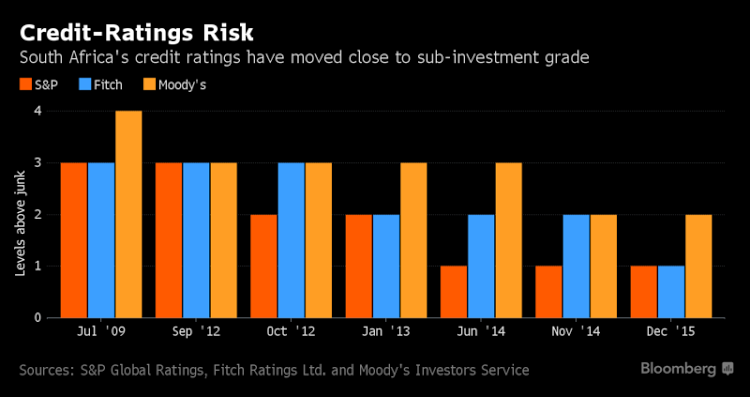

Credit-rating risk.

Slow economic growth and political infighting are some of the key factors rating companies have highlighted as risks to SA’s investment-grade credit rating. While S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings kept their assessments of the nation’s foreign-currency debt at one level above junk late last year, and Moody’s Investors Service’s assessment is one step higher, there is still a chance that SA’s debt will be downgraded this year, according to ETM’s Lamberti.

"The downgrade is tied to how bad the politics and political decisions could be," Lamberti said. "The story with the ratings agencies isn’t really going to change."

Selling our children short again

By Bryan Britton

27 December 2016

By 1994 the Apartheid Government had borrowed against South Africa’s future in an attempt to uphold the untenable principle of separate development. At that time with a debt ratio of about 50% of GDP, our children were faced with a life of repaying their errant parents debt well into the future.

Under the conservative stewardship of first Nelson Mandela and after him Thabo Mbeki, Finance Minister Trevor Manual was allowed to reel in excess expenditure and prudently repay the country’s debt.

By the time Jacob came to power Manuel had performed a minor miracle in reducing the National Debt to Gross Domestic Product ratio to below 30%. South Africa was once again looking attractive to foreign investors and Foreign Direct Investment, upon which the South African Economy critically relies, was looking bullish.

With Zuma at the helm the wheels came off.

With a Debt to GDP ratio back up near fifty percent our children’s’ futures are once more in hock. Additionally, with Zuma relentlessly pursuing a nuclear build program, which the country does not need and certainly cannot afford, our kids, Black, Colored, Asian and White, do not have a future in South Africa.

Zuma has probably already invested the commission on the nuclear deal with his pension manager. And, thereafter greed begets the other six deadly sins.

I have this to say to Zuma: ‘Pay back the money’.

Foreign investors pull plug on SA investments.

Dwaine van Vuuren

President Jacob Zuma and his buddies in the ANC might be impressing Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters supporters with talk of radical economic transformation to slay the imaginary beast of white monopoly capital. But their rhetoric, together with seemingly endless revelations of corruption, is sending foreign investors to distant climes. This worrying development is highlighted in a series of charts put together by Dwaine van Vuuren, a full time trader and stock market researcher. In graphs first published by Sharenet, Van Vuuren outlines the details of how money is moving out of South African assets. Investors are responding to the risks that credit ratings agencies have been highlighting for some time. These include: the country’s exceptionally high unemployment rate; an economy under pressure; perilous government finances; mushrooming red-tape that adds a significant burden to business operations; and political tensions. The rand has been depreciating, but it is no longer a “political shock-absorber”, cautions Van Vuuren. The astute investor reminds his followers that emerging markets have been beneficiaries of a trend in which global investors have been seeking higher income outside low-return developed markets – with the exception of South Africa. Van Vuuren reckons it is not too late to turn this situation around so that money starts flowing back into South African assets. The causes for foreign investors hunting elsewhere for opportunities are all factors we can control because they are domestic – they aren’t related to the global financial crisis, he says. – Jackie Cameron

Dwaine van Vuuren is a full-time trader, global investor and stock-market researcher. His passion for numbers and keen research & analytic ability has helped grow RecessionALERT.com (US based) and PowerStocks Research into companies used by hundreds of hedge funds, brokerage firms, financial advisers and private investors around the world. An enthusiastic educator, he will have you trading and investing with confidence & discipline.

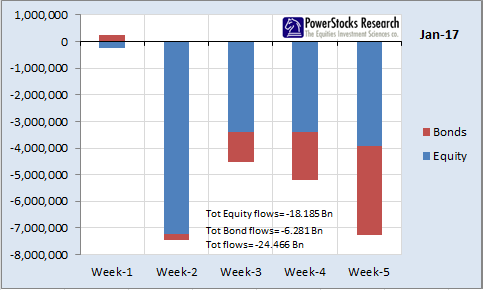

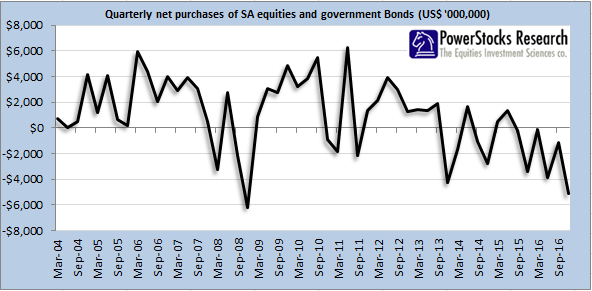

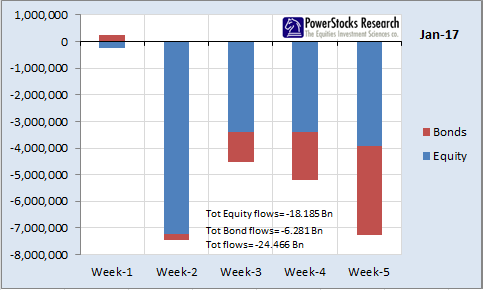

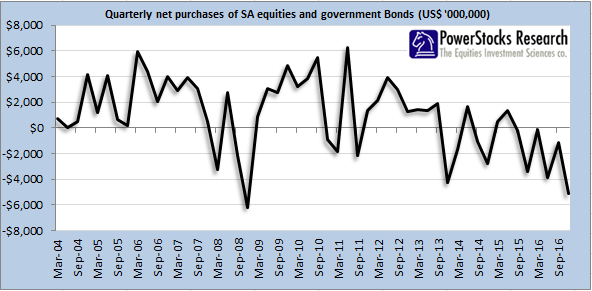

Whilst our past two articles covered faint green shoots to the current malaise our stock market and economy finds itself in, foreigners were still net sellers of R24.4bn in JSE shares and SA government bonds in January 2017. JSE shares accounted for 74% of the outflows:

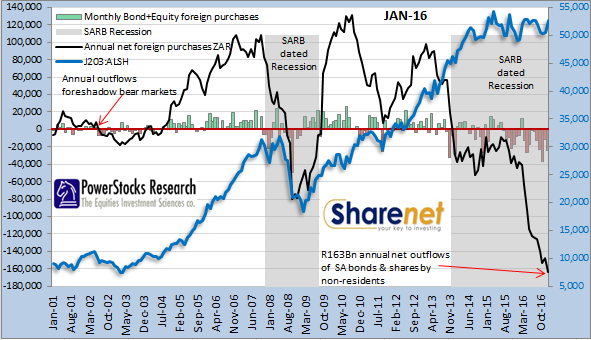

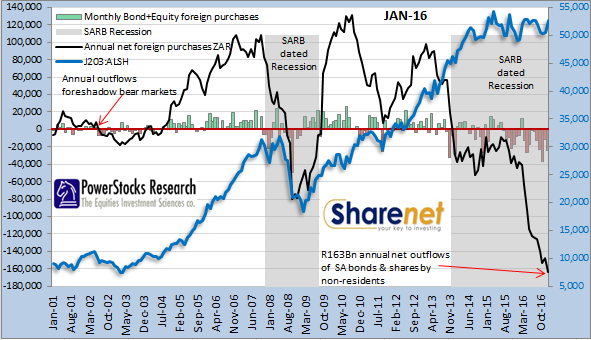

This brings the total rolling annual (12-month) outflows to R163bn:

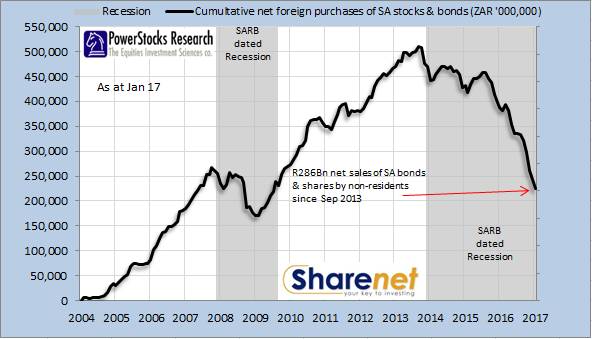

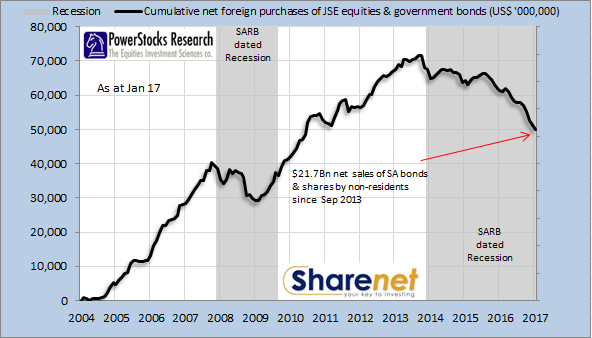

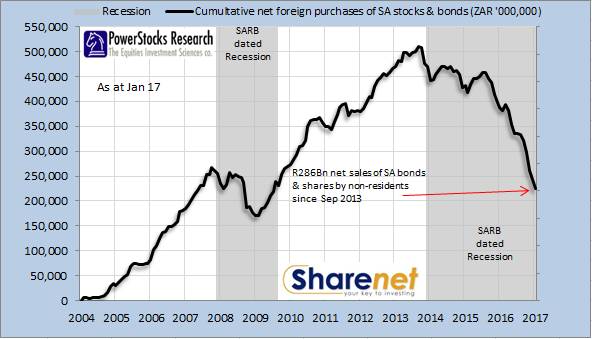

But here is the real eye-opener. Since the September 2013 foreign-flows peak, achieved 2 months before SA fell into a business cycle recession, foreigners have dumped a unprecedented net R286bn in SA equities and government bonds:

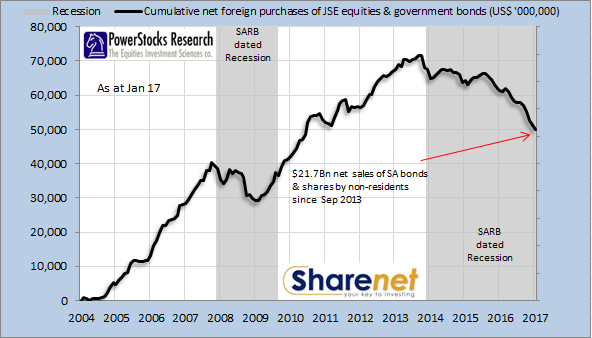

Now the Rand depreciated a massive 60% from 2014 to 2016, so let’s view these outflows in dollars to eliminate the effects of the Rand:

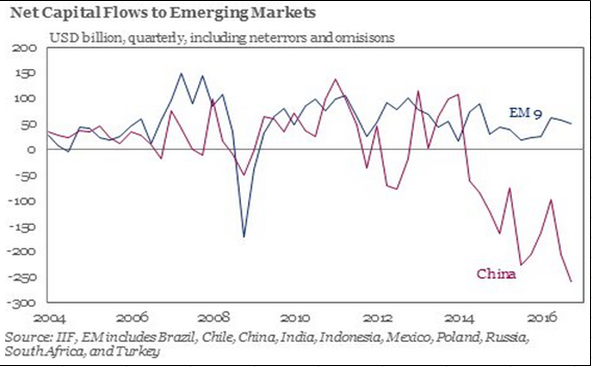

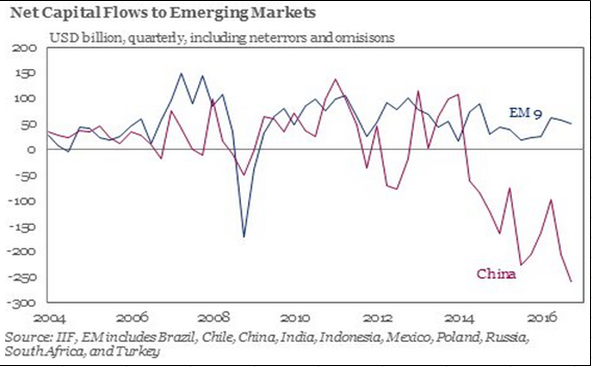

Now many commentators will say that SA is just an unwilling participant in a general emerging market (EM) risk-off and we mustn’t read anything into this. Not so. Whilst EM overall has indeed experienced outflows, these have been isolated to China. If you take China out the equation, EM as a group has experienced inflows for every quarter since the end of the financial crises in 2009:

Let’s look at SA, in US$ on a quarterly basis since 2004:

Why foreigners would be voting with their feet and become large-scale net sellers of our stocks and bonds if we are not caught up in a general EM outflow scenario? The only answer is LOCAL FACTORS. We know what those are, since they are the very things the ratings agencies have been hammering home for the last two years:

- SA’s working age population is growing faster than its economy, and unemployment is at 13-year highs and growing.

- The SA economy is going nowhere, and its growth rate is far below its African and EM averages.

- Government finances are perilous – its debt is at record levels and growing, State owned enterprises (SOE’s) are bleeding us dry and corruption/wasteful expenditure is widespread and unchecked.

- Lack of clear policies across various sectors has led to a plunge in confidence and a widespread private sector investment strike.

- Government, Business & Labour focusing on narrow self-interests instead of working together in unison for the best of the country as a whole.

- Most interventions by the government in the economy are focused on regulation and red tape as opposed to growth enhancement and confidence building.

- Protracted political tensions generate policy uncertainty and impede structural reforms.

- The economy has failed to benefit from the collapsing Rand (the Rand is no longer a traditional shock-absorber.)

The sad thing is that these are mostly factors within our control – not external factors we have no control over. And we must stop blaming the global financial crises – that ended over 6 years ago.

Inflows are but one of 8 major items the stock market and economy needs to give a boost. But even with outflows, if enough other items start showing green shoots we may be able to overcome the effects of mild outflows.

World Bank to SA parliamentarians: The key to economic growth is private investment

Marianne Merten

15 Feb 2017 1 Reaction

Amid the niceties that accompany briefings to parliamentary committees, the World Bank on Wednesday delivered a hard message: stop investment tax incentives in sectors where they don’t work, such as mining, and move them to manufacturing, agriculture, trade and construction which are generating jobs and add value. Reversing the decline in direct and private investment was key to job creation and boosting economic growth, the World Bank said, as the current negative investment levels meant South Africans have got poorer every year since 2012.

The issue of direct and private investment is a prickly pear. Policy uncertainty, a volatile currency, political interference and state capture are often cited as obstacles both domestically and internationally by bodies such as ratings agencies.

Trade union federation Cosatu and others point out that South Africa’s own corporate sector is holding back an estimated R600-billion that could and should be invested locally. And most recently, fingers are being pointed at white monopoly capital by those determined to establish an alternate narrative to the prevalence of politically connected tenderpreneurs.

Government, while maintaining it has the correct policies to sell “Team South Africa” internationally that have staved off ratings downgrades in 2016, also highlights its own prowess: state-driven investment through its R1-trillion infrastructure programme and job opportunities through government initiatives such as the Expanded Public Works Programme.

All this unfolds in a deeply fractured political landscape. And last week’s presidential State of the Nation Address (SONA) emphasized the radical socio-economic transformation to change the structural inequalities that the ANC lekgotla resolved on, some four years after radical transformation was adopted by the governing ANC at its December 2012 national conference.

On Wednesday, a week before Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan delivers Budget 2017, the message from World Bank Group Programme Leader: Equitable Growth, Finance and Institutions, Sébastien C. Dessus, was clear: private investment is vital to achieve the National Development Plan’s (NDP) aim to reduce poverty, inequality and unemployment by 2030.

“Key to accelerate (economic) growth is private investment. Private consumption is very much constrained by the debt of households, by unemployment of the households,” said Dessus. “By better targeting of investment tax incentives, poverty can be reduced through job creation at no additional fiscal cost.”

Private investment, supported through tax incentives, would have a significant impact amid economic growth expectations at best described “modest” and “fragile” at between 1.1% and 1.8% over the next two years.

Yet the current incentive structure appears to be insufficiently focused for economic development. Mining, with its set of incentives, generates a social return 3.4 times lower than manufacturing for investors looking to get a 10% return on investment. Or to put it bluntly: despite incentives, mining investments generate lower social returns than investments in manufacturing, trade, agriculture and services.

In those sectors the multiplier effect of investment on job creation is the greatest – and should therefore be supported, according to Dessus. While some of South Africa’s existing investment tax incentives are working, and generating benefits such as jobs, some are not. “It they are not delivering, it is a waste of resources.”

He reserved comments on the motor industry incentives of the Industrial Policy Action Plan (Ipap), which government has touted as successful on the back of multimillion-rand investments by international motor manufacturers. As these incentives were introduced only two years ago, and more research was needed.

However, Dessus cautioned about corporate concentration, saying it would be naïve to think these companies “do not take advantage”, impacting on economic growth through higher input costs and barriers to entry by smaller enterprises. In South Africa, 1% of the top companies generate 60% of added value and 50% of jobs. “The future of South Africa’s economy will depend on how these firms behave,” he said.

About 600,000 jobs must be created annually to achieve the NDP goals, but only around 250,000 have been achieved on average every year since 2012, according to Dessus. This echoes National Treasury indicators in last year’s Budget. Job creation in the first three quarters of 2015 stood as 19,000 in the formal sector and 273,000 in the informal sector, the 2016 Budget Review said, adding, “The number of South Africans categorised as long-term unemployed 5.7% higher than in 2014.”

At these levels, job creation falls short of what is needed to achieve NDP goals. In addition, concerns are being raised over the ballooning public sector wage. While Budget 2016 announced that vacant posts outside crucial sectors like health, teaching and policing were frozen in efforts to cut costs, the outcome of this on government’s cost cutting remains to be seen.

But it wasn’t just about private investment at Wednesday’s World Bank briefing to the standing committee on appropriations. Policy certainty – it seems South Africa’s consultative processes generate confusion among those abroad – was important, but so was quality education.

According to the World Bank’s South Africa Economic Update Issue 9, the South African education sector faces many challenges “in ensuring all children have the knowledge, skills and attributes they need to be successful workers and citizens”. And this is not only because around half of those who start school drop out before reaching matric. “Only 24% of Grade 5 children can answer correctly the following question: ‘Pam has ZAR40. She spends ZAR28. How much money does she have left?’”

Education had one of the largest government expenditure bills, next only to Social Services which pays out social grants to 17-million poor South Africans. This trend is expected to continue in next Wednesday’s Budget.

A tough balancing act in a tough domestic and global economic climate is expected: some R28-billion needs to be found, most likely through additional taxes, as revenue collection has fallen short.

For the past two years National Treasury held off on introducing a carbon tax, an incentive to reduce greenhouse gasses. Although the sugar tax was mooted for implementation from April 2017, the law needed to do so is still in draft form as Parliament is holding public hearings. It was expected to raise up to R11-billion.

It will be up to the finance minister to ensure South Africans swallow what no doubt will be a bitter-sweet pill. But the World Bank message on private investment as crucial to boost economic growth to redress unemployment, poverty and inequality, may be a bitter pill for a government that has taken political pride in being the main mover in addressing developmental challenges. DM

Swelling the state coffers for dysfunctional, corrupt emptying

By Dawie Roodt*

whatsapp

Ineptocracy – it’s an appropriate term used by economist Dawie Roodt, especially as Pravin Gordhan prepares to swell the State coffers (at considerable extra cost to the mostly-efficient private sector), which are then quickly emptied by mostly-unaccountable bureaucrats. He’s obviously run repeatedly headlong into mindless red tape and, like many of us, has watched the civil service grow bloated and more mindless, consuming a huge portion of the State fiscus while delivering bang for buck that would put you and I into liquidation. As professional politicians and career bureaucrats collude to regulate and dominate our lives at national, provincial and municipal level, tying us up in oft-unnecessary red tape to justify their jobs, parastatals pretending to be businesses swallow billions of taxpayer rands mainly through pure inefficiency, but also through corruption and ‘snouting’ by well connected, equally dysfunctional service providers. Accountability – the cornerstone of any efficient business – goes by the wayside as the goal to enrich as many close pals as possible too often becomes the driving force of operations. The goods and services for which all these entities supposedly exist become a vague concept that might raise a frown were any ‘customer’ to query their absence at the front desk. – Chris Bateman

It’s budget time again and economists and analysts are expected to say what they think the minister of finance will announce in his speech. This is also a time when economists get the opportunity to “advise” on all things fiscal: taxes, state spending, borrowing, debt, key ratios and mysterious things designated by incomprehensible acronyms. So here I go; but first some context.

Lest we forget, the state is there to serve the people. But civil servants (a contradiction) and their bosses, the politicians, have morphed into a social class of their own. Especially since World War II, a new phenomenon has emerged: the rise of the career bureaucrat and the professional politician.

More magic available at www.zapiro.com

Much of this happened because of the ideas of influential thinkers. Of these thinkers, one individual stands out, John Maynard Keynes. Without going into too much detail, his main thesis was that economies often experience insufficient demand. Under such circumstances, it is acceptable for “governments” (states) to boost demand (spend more). Since then it has become mainstream for governments to get actively involved in the economy, not in providing goods and services as such, but to emphasise and augment demand.

And they took to their new role with gusto. State spending ballooned, creating the ideal breeding ground for rent seekers; the career bureaucrat and the professional politician (another contradiction). Governments dramatically increased in size and so too did the tax burden and state debt. Today “governments” are by far the most important economic force in just about all countries of the world and consequently, the productive sector – the private sector – carries a massive and rising tax burden. In fact, I think that the Trump- and Brexit phenomenon (and more shocks are likely this year) is partly because people now recognize the new “uber” class for what it is – a suppressive force that imposes an unsustainable tax burden – and the people are getting restless.

South Africa is no different. The relative size of the state has increased massively in recent decades. “The state”, of course, is much more than just what the minister of finance is going to talk about in the budget. The state also includes the provinces, local authorities and the parastatals. In fact, the new ruling class has become so interventionist that the definition of “the state” must be extended, for the state now regulates all our economic, social and normal day-to-day activities. The state is everywhere! And to add to this burden, the professional polit