A real economy is vastly more complex than our simple

economy and its money is also more complex. Perhaps the biggest difference is

that in the simple economy (with jewellery as money) money was itself wealth - created

by labour - and the money supply could be expanded or contracted at will

simply by producing more or less of it. That was a great strength. The money

supply could respond quickly and easily to any shortage or oversupply, so the

quantity in circulation remained close to the level that the economy required. Money

in a real economy is very different in that it is not wealth and not a product

of labour, so there is nothing that ordinary people can do to bring more into

circulation except by borrowing from banks, and that incurs heavy penalties in

the form of interest payments - more on that in Part 2. Nevertheless in spite

of major differences there are similarities. Saving money has a similar effect

and is discussed in the following two chapters. The required quantity and rate

of spend of money are also similar, in that they should be sufficient to allow

all transactions to take place that people want and have the means for -

meaning that sellers have goods or services to sell, and buyers have saleable

assets (including their own future labour) equal to or in excess of the

transaction value - we'll refer to these as legitimate transactions. Indeed

this is precisely what money is for, to enable people to exchange different

forms of wealth with each other.

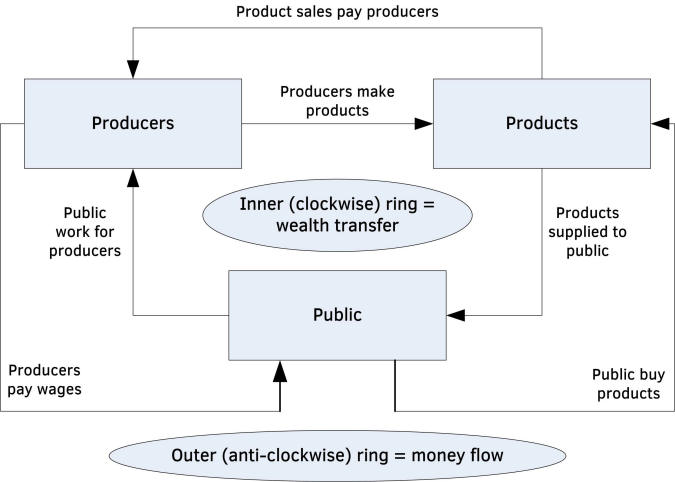

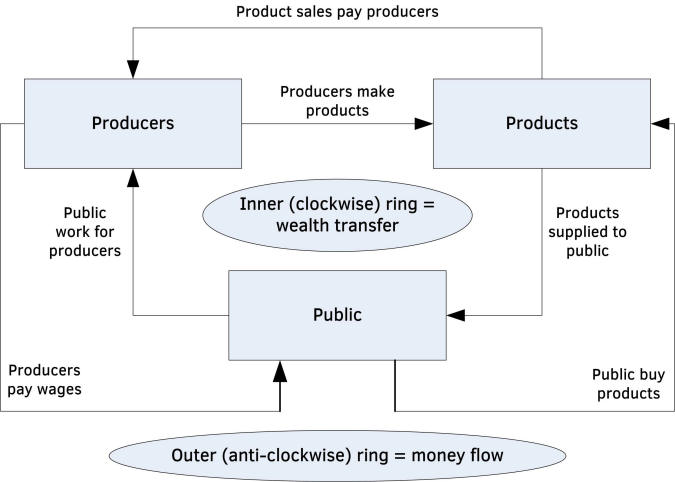

A simple diagram illustrates the flow of money and transfer

of wealth when the economy is working properly.

Figure 14.1: Wealth transfer and money circulation

Although it is the same money that circulates

continually around the economy, it is new wealth that is created in each

transaction. Money circulates but isn't consumed, whereas wealth is consumed or

utilised but doesn't circulate. For wealth to be created, traded, consumed and

utilised money MUST circulate.

A simple story illustrates this important effect. A person

loses a £10 note in a pub one night. When clearing up the landlord finds it and

pockets it. Next morning he spends it on a haircut and the barber then uses it

to buy his lunch from the lady who owns the local cafe. The cafe owner gives

the note to the window cleaner in return for his services, and in the evening

the window cleaner buys a round of drinks with it in the pub. Later that night

the person who lost the note returns and asks the landlord if anyone found it. The

landlord, being honest, says that he found it, and returns it to its original

owner. The £10 note is now back where it started from, having circulated around

the local economy and made possible the creation of £40 worth of wealth in the

form of a haircut, a lunch, window cleaning and a round of drinks. It is the

same money that changes hands in each transaction, but it is new wealth that is

created and consumed. Money's role as a lubricant is clearly seen in this story

- it is the same money that enables every transaction just as it is the same

oil that lubricates the moving parts in every engine revolution.

If we remove the money from the story we can see what each

person gets and gives. The landlord gives a round of drinks and gets a haircut;

the barber gives a haircut and gets a lunch; the cafe owner gives a lunch and

gets her windows cleaned; and the window cleaner cleans windows and gets a

round of drinks. The notable feature is that what everyone gets is from a

different person than the person they gave something to, which is exactly how

the real economy works. It is money that allows multi-person exchanges, which

is quite marvellous when you stop to think about it. We are so used to it that

we take it for granted, but without money it would be impossible to keep track

of who owed what to whom, and therefore very many fewer transactions would be

possible.

What is really happening is that we are all working

for each other, both in this story and in the real economy, and money is the

lubricant that makes it possible.

The above story illustrates another important point. For the

economy to benefit new wealth must be created and become available for use. Money

for new wealth is payment for the time, effort and expense involved in creating

it. When existing wealth is bought (wealth that has already been bought by

someone else when it was new) it doesn't affect the economy because the economy

has just as much wealth after the exchange as before it. All that happens is

that money and existing wealth change owners.

All wealth in the story is new wealth. When existing

products are exchanged the only new wealth, if any, is the service of making

the products available to buy, not the products themselves. Therefore a good

second-hand car dealer provides the service of bringing a range of cars

together, cleaning, repairing and servicing them, having them tested and

provided with roadworthiness certificates, providing warranties and advertising

them for sale. This service represents the new wealth that is created, which is

exchanged for an income when buyers buy the cars. The dealer's profit is the

excess of income over the cost of the cars together with all other associated

expenses and that profit represents payment for the service that the dealer

provides. In this case the service (new wealth) provided by the dealer for a

particular car is consumed as soon as the car is bought, as are many services,

but it nevertheless added to total wealth prior to its consumption - as indeed

does all wealth. The cars themselves don't represent new wealth because when

they were new they were sold to someone else, who merely transferred them to

the dealer in exchange for money.

It is important to separate spending on new wealth

creation from spending on existing wealth transfer. Only the first adds to

total wealth and therefore benefits the economy. The second adds no new wealth

so it does nothing for the economy though it does benefit the parties directly

involved.

If I sell my car to a friend then no new wealth is created,

all that happens is that the car (existing wealth) and money change hands. The

economy isn't affected by this exchange. This also applies if the car I sell to

my friend has serious faults that I keep quiet about and charge twice the price

it is really worth. I have made a profit by deception but that profit isn't

income in exchange for new wealth because my friend, who is now my ex-friend,

hasn't received anything in exchange for it except perhaps the satisfaction of

giving me a black eye! In effect the profit represents a money transfer

(extraction) by exploitation. In this case my deception becomes clear soon

enough, but in many transactions deception or information hiding is much more

subtle, especially in banking and financial trading as will be explained later,

and as a result the bulk of what is thought to be new wealth represented by the

services that those sectors provide is really extraction of existing wealth

from others by exploitation. This is considered in detail in Part 2.

Making a profit from another's ignorance is not

wealth creation; it is wealth extraction by exploitation.

Recall that wealth extraction is charging more for a product

or service than a fully informed and unexploited buyer would be willing to pay.

When money is taken out of the picture and wealth alone is

considered it is clear that the economy is a giant human-powered wealth creating

and using machine, where people work continuously to produce the products that

people need and want, and people continuously use them. Provided that the

machine keeps on producing and using then all is well. To keep the machine

working we need a means of persuading people to create wealth and to part with

it to others without immediately receiving an equivalent quantity of wealth in

return (that would be barter and as already discussed barter is very difficult

and usually impractical). Hence what is needed is trust, the giver of wealth

needs to trust that he or she will receive back the value of that wealth in due

course, and that's what money provides. As long as people believe that money

will retain its value then to an individual or business money is just as good

as wealth and people have no difficulty in exchanging wealth for money. All

that is needed therefore is for there to be sufficient trust, embodied in

money, to allow all legitimate transactions to take place. It sounds simple -

and it could be - but it isn't.

Sadly controlling the money supply in a real economy, given

the way the system works, is very difficult indeed. This is why inflation and

deflation strike such fear into all participants in the economy, especially

governments, which can stand or fall on the behaviour of the money supply, as

indeed can businesses, families and individuals.

This is a very peculiar situation. We have a system that has

been invented and designed by humans - there is nothing natural about money -

and yet it behaves as though it was a natural phenomenon like the weather,

beyond human control. Governments try to exercise a measure of control in the

form of fiscal policy - taxing, borrowing and spending; and central

banks try to exercise a measure of control in the form of monetary policy

- setting the bank rate (the interest rate charged to commercial banks for BoE reserves

- see chapters 39 and 41) and buying and selling securities such as government

bonds and sometimes other assets in the market. However these merely provide

fine-tuning and are only successful in the absence of major economic turbulence

brought on by external shocks (natural disasters, raw material shortages,

pandemics etc.) and internal events (asset bubbles bursting, excessive lending

and borrowing, major debt defaults, currency attacks by speculators etc.). In

these circumstances the levers available to government and central banks prove

hopelessly inadequate, and the economy and everyone in it are tossed about like

small boats on a stormy sea. The means by which governments and central banks

try to control the money supply, why they are inadequate, and how it could be

made so much better are examined in chapters 86 and 100.