This discussion expands on and reinforces the 'paradox of

thrift' message for the simple three-person economy. I believe that it is worth

labouring the point because it is so important. To begin let's simplify things

in order to highlight the effects.

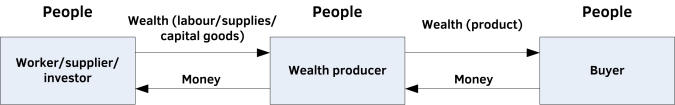

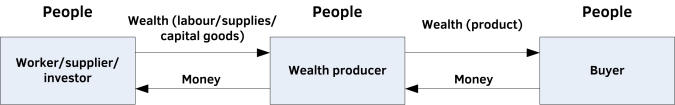

Figure 15.1: A basic transaction structure.

Figure 15.1 indicates simply that regardless of what form

transactions take what happens is that people always transact with other people.

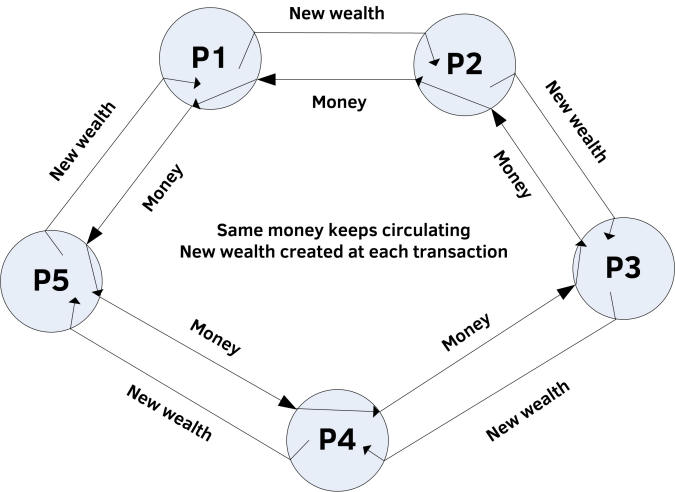

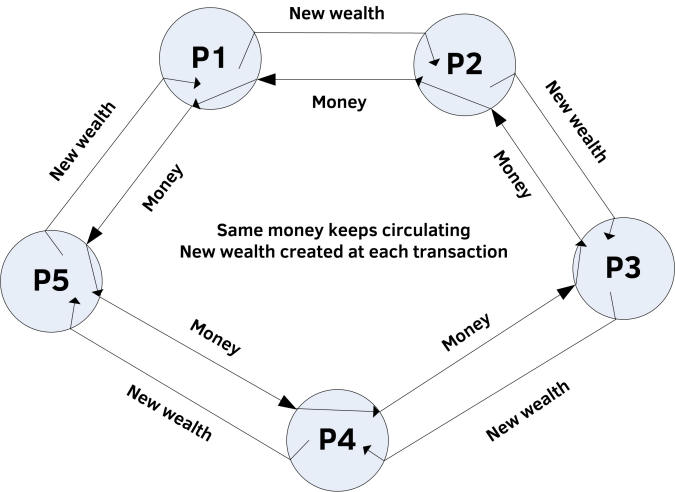

Figure 15.2 completes the circle of transactions which reflects the situation

in a real economy. Although this is a simplified picture it is able to

illustrate the effect of saving money on wealth creation.

Figure 15.2: People transacting with several other people

where the transactions come full circle as they do in a real economy.

Let's say that P5 ('P' is for person), instead of saving

money, decides to save half the wealth that she receives from P4 instead of using

it. She pays P4 the normal sum of money and receives the normal amount of

wealth in return. She puts half on one side for safe keeping and uses the other

half. P4 doesn't care what P5 does with the wealth, her only concern is being

paid for it. P4 uses the money to buy the normal amount of wealth from P3, P3

from P2, P2 from P1, and P1 from P5. Nothing has changed as far as all the

other people are concerned, this little economy keeps on working just as

before, but with P5 saving half the wealth she has bought. P5 can go on saving

bought wealth if she wants to, and so can any or all the others.

All well and good so far, and all is as expected. But now

consider what happens if instead of saving wealth P5 decides to save money. Money

needs to circulate, so saving it can be expected to cause problems, and it does.

Saving money is very much more likely than saving wealth because money can be

exchanged for anything. She pays P4 half the normal sum of money and buys half

the normal amount of wealth from P4. P5 is happy with that, she didn't expect

any more than half the wealth, after all that's her sacrifice for saving the

money. But what about P4? P4 isn't happy at all. P4 has only sold half the

wealth she has produced so the other half remains unsold. Even worse she can

now only afford to buy half the wealth that P3 has produced, so half of P3's

wealth remains unsold, and the same for P2 and P1. When P1 comes to buy the

wealth that P5 has produced again she can only buy half the wealth so half of

P5's wealth remains unsold. The net effect is that everyone is left with unsold

stock and only P5 has any extra money. If P5 had intended to keep saving money

then she now finds that she can't because her income has dropped by half. Let's

say she spends all her remaining income because she can't cut back any more, so

she buys the unsold stock that P4 was left with after the first round. Similarly

P4 buys P3's unsold stock, P3 buys P2's, P2 buys P1's, and P1 buys P5's. Now

there is no unsold stock, but only half the money circulating in the economy. As

a result all decide to cut back on production to avoid being left with unsold

stock, and the economy eventually settles down with each producing half the

normal amount of wealth and half the original money circulating. The economy is

now stable again, but P5 can't save any more money, and by saving just half of

one payment great damage has been done to everyone including P5, and there is

only half the employment there was originally. This is again Keynes' paradox of

thrift that was referred to earlier. Saving money is another example of the

confusion between money and wealth. We think that saving money is the same as

saving wealth, but as we have seen it as anything but.

When spending drops the economy declines until

production matches the new lower level of spending.

This is a simplified illustration and having so few

participants exaggerates the effects, but the mechanism it illustrates is

accurate and the paradox is very real and very damaging, and is exactly what

happens when people stop spending for any reason, and not just any form of

spending, but spending on new wealth production. It is what causes recessions

and depressions.

Whenever someone cuts back on spending on newly

created wealth, either someone else must spend to make up the difference or

there will be unused services or unsold stock, which will only clear when

production has been scaled back to match the reduced level of spending, the

result of which is unemployment.

This outcome is not widely recognised. It illustrates

clearly the dangers of treating money as wealth, as most people including

economists and especially politicians do all the time. The essential factor

that makes it happen is saving that which is intended for trade - i.e. money -

rather than saving that which is bought for use - i.e. wealth. Hence it is very

much more likely in economies that use money - regardless of the form that it

takes - because to have the same effect in a barter economy one would have to

save the wealth that one produced for sale to others instead of using it

to buy wealth from others, and that is much less likely because if that wealth

was wanted for saving then sufficient would be produced both to meet one's own

saving requirements and to use for buying wealth from others. In a barter

economy the wealth used to buy things is produced by the buyer - its

availability is within the buyer's own control, whereas in a money economy the

money used to buy things can't be produced by the buyer, it has to be obtained

from someone else - from money received as income.

Storing wealth for use in the future rather than using it

now is a prudent thing to do as it increases security, providing a buffer

against unforeseen events that can damage later production. Storing money seems

to serve the same purpose in that it provides entitlement to future wealth, but

it is not at all the same thing because as we have seen money is needed to

provide another person's income, and the more that is stored the less future

wealth that person can create. So although storing money seems logical and

makes sense for the individual, it is counter-productive for the economy as a

whole. If a lot of people store money at the same time then the only way that

the economy can avoid harm is if someone else (normally the government) spends

sufficiently to compensate.

Delaying use by storing wealth for the future is

prudent, but storing money for future wealth entitlement is counter-productive

because it reduces the amount of wealth that can be created.

The foregoing arguments show why the gold standard - when

money was fully guaranteed by gold - was a very poor basis for an economy. The

supply of money depended on the supply of gold, and when that was in short

supply - due to spending on too many imports or hoarding at times of

uncertainty about the future - wealth creation necessarily slowed down and

people suffered as a result. The only way to get more money into the economy

was for the rulers to take it from the hoarders (difficult because gold is easy

to hide) and spend it, export more goods to earn gold from abroad, or conquer

foreign countries and take control of their gold. It led to a world of hostile

competition

In 1924 in his influential publication 'Monetary Reform',

Keynes famously said in response to those who advocated a return to the gold

standard:

If we restore the gold standard, are we to return also

to the pre-war conceptions of bank rate, allowing the tides of gold to play

what tricks they like with internal price level, and abandoning the attempt to

moderate the disastrous influence of the credit-cycle on the stability of

prices and employment? ... In truth the gold standard is already a barbarous

relic. (Keynes 1924 p172)