It will be useful to consider all the main transactions that

a bank (i.e. a retail bank) undertakes, to see when and how money is created

and destroyed. It will be useful also to explore the main transactions of

government in the same way, because government transactions usually involve

banks, and the insights gained can be used in Part 4 to examine how the

government currently raises money and to consider how it might raise money more

beneficially.

The major point to bear in mind is:

New bank money comes into existence whenever a bank

makes a payment in bank money (increase in customer liabilities) and goes out

of existence whenever a bank receives payment in bank money (decrease in

customer liabilities).

Given the above basic principle we can set out the various

transactions that banks undertake:

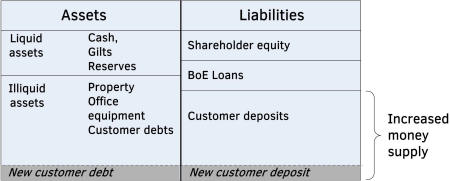

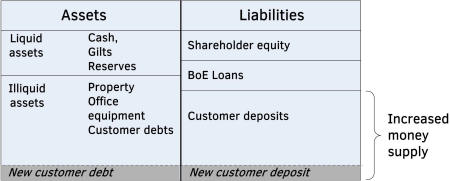

i. Bank loan to a borrower

with an account at the lending bank (figure 44.1): a loan agreement signed by

the borrower is received by the bank's loan account (account debited), creating

an asset for the bank. At the same time bank money is made available to the

customer and recorded as a bank debt in the customer's deposit account (account

credited), creating a liability for the bank. It might appear that since bank

money has been received by the customer the deposit account should be debited,

but remember that it is the customer who has received the money and the

customer is external to the bank. In order for the customer to receive the

money the bank must take it from somewhere, and that somewhere is the customer's

deposit account, so the account is credited.

Figure 44.1: Balance sheet expands, new asset balances new

liability.

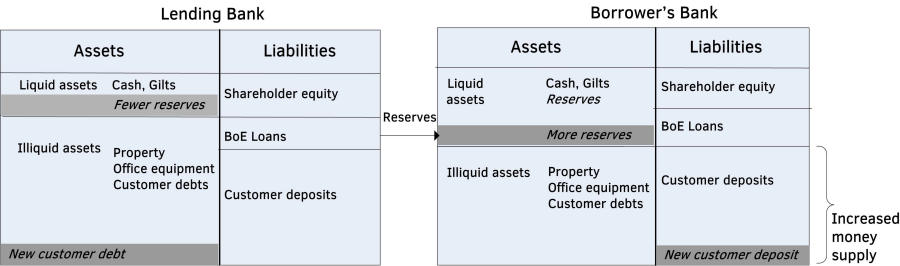

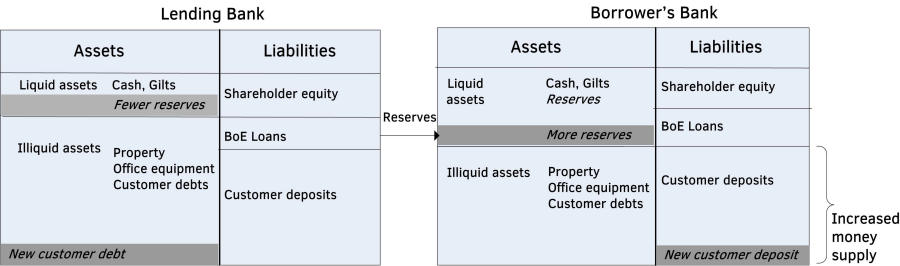

ii. Bank loan to a borrower with

an account at another bank (figure 44.2): the lending bank sends BoE reserves

to the borrower's bank (lending bank reserve account credited so an asset is

destroyed), and the loan agreement signed by the borrower is received by the

lending bank' loan account, which is debited (an equivalent bank asset is

created). When the borrower's bank receives the reserves its reserve account

is debited (an asset is created), and a new debt to the borrower recorded as a

credit in the borrower's deposit account (an equivalent bank liability is

created). The net effect is exactly the same as in case (i): bank money (a

liability) has been created and an equivalent asset in the form of the loan

agreement has also been created. The borrower's bank merely acts as an

intermediary in the process, receiving reserves in return for crediting the

borrower's account.

In this case the lending bank doesn't create money; it

'buys' the new customer debt with state money - BoE reserves. But, importantly,

that state money isn't given to the customer who takes on the debt; it is

passed to another bank to compensate it for creating money and thereby taking

on a new liability to the customer. Bank money has still been created, but not

by the lending bank. In reality all banks lend money all the time, so for

almost every loan that bank A gives and sends reserves to bank B, bank B also

gives a similar loan and sends reserves to bank A, so the net effect is very

many loans and very little reserve transfer.

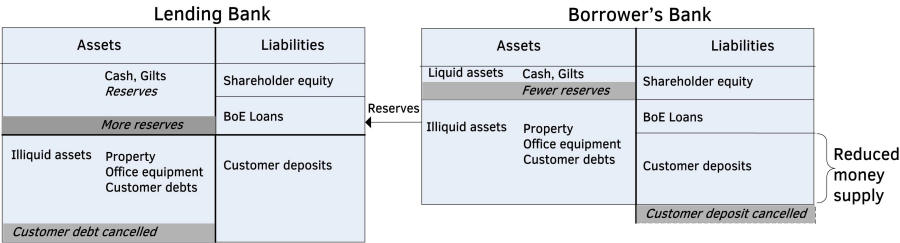

Figure 44.2: No change in lending bank balance sheet; it

gains one asset (customer debt) and loses another (reserves). Borrower's bank

balance sheet expands; it gains an asset (reserves) and a new balancing

liability (customer deposit).

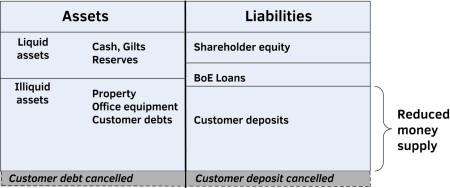

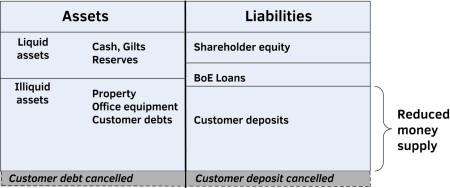

iii. A borrower with an account

at the lending bank repays a loan (figure 44.3): the customer pays the bank

which passes that value to the customer's deposit account (account debited - bank

money representing a bank liability is destroyed), the original loan agreement

is stamped as paid (in effect sold back to the borrower in return for the

repayment) and the bank's loan account is credited (an equivalent asset is

destroyed).

Figure 44.3: Balance sheet shrinks, an asset loss balances

a liability loss.

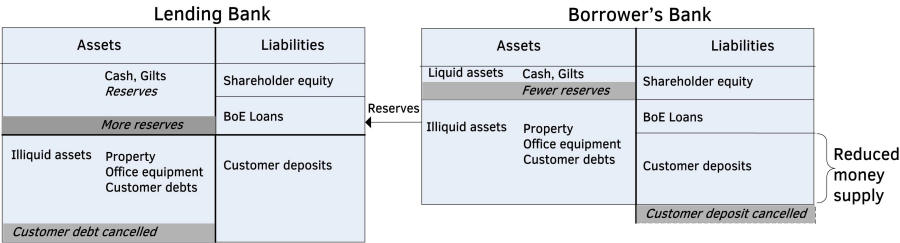

iv. A borrower with an account

at a bank other than the lending bank repays a loan (figure 44.4): the borrower

transfers money from their bank account to the lending bank, which receives

reserves from the borrower's bank and debits its reserve account accordingly

(an asset is created). The original loan agreement is stamped as paid and the

bank's loan account is credited (an equivalent asset is destroyed). The

borrower's bank credits its reserve account (an asset is destroyed) and debits

the borrowers account (an equivalent liability is destroyed). The net effect is

exactly the same as in case (iii): bank money (a liability) has been destroyed

and an equivalent asset in the form of the loan agreement has also been

destroyed. The borrower's bank merely acts as an intermediary in the process,

sending reserves in return for debiting the borrower's account.

Figure 44.4: No change in lending bank's balance sheet, it

gains one asset (reserves) and loses another (customer debt). Borrower's

balance sheet shrinks; it loses an asset (reserves) and loses a liability

(customer deposit).

For simplicity the remainder of these examples will just

involve a single bank, other banks may be involved in reality but as above they

only act as intermediaries. Also the effects on assets and liabilities and the

money supply will just be stated rather than illustrated.

v. A borrower pays interest on

a loan: bank money is received by the bank (debited from the borrower's

account - a liability is destroyed), and the bank gives its shareholders the

equivalent value (the shareholders' account is credited - an equivalent

liability is created). Recall that the shareholder equity account is a

liability of the bank because it 'owes' this amount to the shareholders.

vi. A bank pays an employee's

salary: bank money is made available to the employee and the bank debt recorded

in the employee's deposit account (account credited - liability created), and value

is received (debited) from the shareholders' equity account (an equivalent

liability is destroyed). In effect the shareholders have taken on the debt

represented by the employee's salary by reducing their holdings in the bank.

vii. A bank buys office

equipment: bank money is made available to the supplier and the bank debt recorded

in the supplier's deposit account (account credited - liability created), and

the bank's asset account is debited (office equipment received - an equivalent

asset is created).

viii. A bank pays a dividend to

its shareholders: bank money is made available to the shareholders and the bank

debt recorded in the shareholders' deposit accounts (accounts credited -

liabilities created), and value is received by the bank from the shareholders (their

equity account is debited - an equivalent liability is destroyed). In effect

the shareholders have been given value in the form of bank money and in return reduce

their holdings in the bank.

For vi, vii, and viii recall what was said in chapter 39:

bank money created for a bank's own purchases (salaries, bonuses, dividends,

goods and services) is taken from debt interest payments that were destroyed

when received, so there is no net creation of new money for these purchases.

ix. A customer withdraws cash

from an ATM: bank money is received by the bank (debited from the customer's

account - a liability is destroyed), and cash is given to the customer (credited

to its cash account - an equivalent asset is destroyed). Note that a bank can

only obtain cash from the BoE by paying reserves for it; it can't create and

use bank money for the purpose because the BoE doesn't accept bank money. Similarly

if a bank pays cash to the BoE then it receives reserves in exchange. Note that

in this case the bank discharges it's liability to the customer by paying out

state money.

x. A customer pays cash into a

bank account: bank money is made available to the customer and the bank debt recorded

in the customer's deposit account (account credited - liability created), and cash

is received by the bank's cash account (account debited - an equivalent asset

is created).

xi. A customer repays a bank

loan with cash: this is an interesting case in that no bank money is involved;

one bank asset (the customer debt) is exchanged for a new asset (the cash). The

bank money that was created when the loan was originally taken out was

destroyed when the cash was handed over from a bank to a customer, regardless

of who got it and how it found its way to the borrower to repay the bank.

xii. A borrower defaults on a

loan repayment: this is another interesting case in that again no bank money

is involved. The bank money created in response to the original loan remains in

the banking system, but not in the borrower's account because he or she can't

pay. The asset in the form of the loan agreement that the bank thought had

value is now seen to have none, so on the balance sheet the loan account is

credited (an asset is destroyed), and to balance it the shareholder equity

account is debited (an equivalent liability is also destroyed). In effect the

debt is transferred from the original borrower to the shareholders and the bank

itself has lost that amount of value.

The remaining transactions involve government borrowing by

selling and repaying bonds (gilts) to banks and others. They are quite complex

but are included to show the mechanisms involved, and to show that to banks

gilts are just the same as any other debt that they own, in that when banks buy

gilts they do so with created bank money - not as individual banks but in

conjunction with other banks. This will be taken up in chapter 89 on government

borrowing.

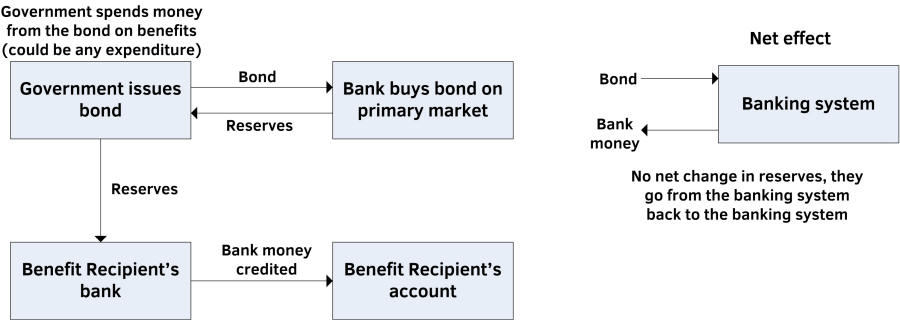

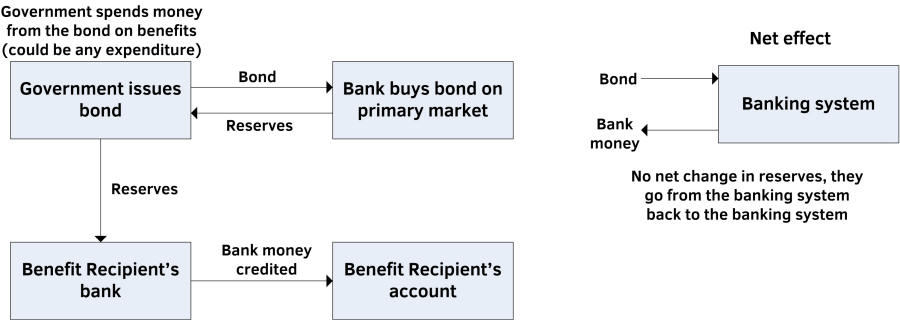

xiii. A bank buys a government

bond directly from the government (i.e. on the primary market): government

bond purchase is very important for banks because they can be used as

collateral for loans of reserves, so if the bank can create money to buy them

then it is in effect able to create the means to obtain reserves at no cost. However,

since one organisation with a reserve account (the bank) is dealing with

another organisation with a reserve account (the government), no bank money is

involved. The bank merely transfers reserves to the government in return for

the bond (its reserve account is credited (an asset is destroyed) and its bond

account is debited (an equivalent asset is created). It seems therefore that a

bank can't create money to buy a bond. However, if we pursue the matter further

we see that the government wants the money in order to spend it in the economy,

on public servant salaries, benefits, the NHS, subsidies and many other things.

When it spends this money bank money is created - reserves are

transferred from government to the recipient's bank (increase in bank assets),

and the bank credits the recipient's account with new bank money (increase in

bank liabilities). Hence the banking system as a whole can create money

to buy bonds, though the original bank that bought the bond won't necessarily

be the bank that creates the money. What has happened, after the money from the

bond has been spent by the government, is that the banking system has created

the money to buy the bond, and thereafter enjoys the interest that is paid on

the bond from the taxpayer - for nothing in return - nice! Also, perhaps even

more importantly, it has increased its stock of high quality assets, and

thereby improved its position with respect to the capital and liquidity ratios

that banks are bound by, and as a result it can lend more and further increase

profits. Although this process involves the banking system as a whole, all the

players are involved so they all share the benefits. This is shown in figure

44.5.

Figure 44.5: How the banking system creates the money to

buy government bonds on the primary market.

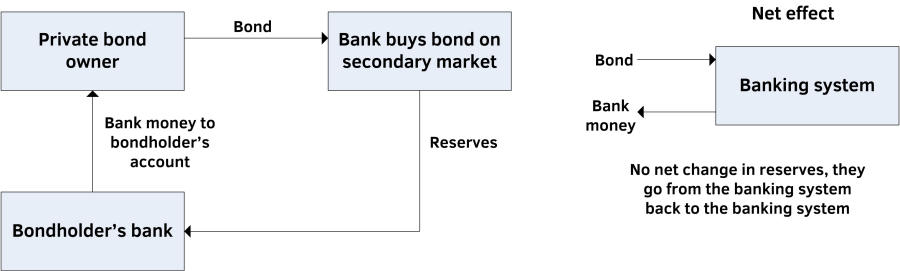

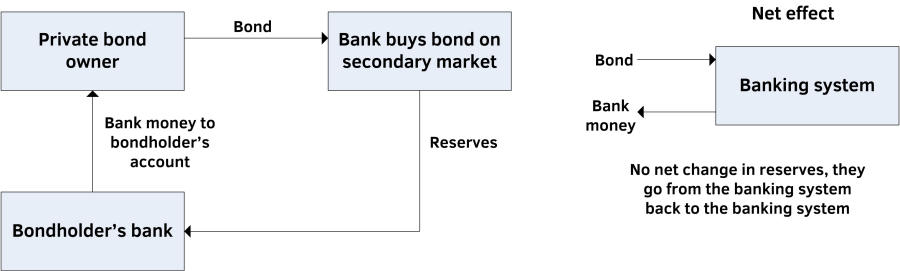

xiv. A bank buys a bond on the

secondary market (i.e. from someone other than the government): here the bank

creates the money directly by crediting the account of the seller (a liability

is created), and debits its bond account (an equivalent asset is created). The

bond seller might well bank with a different bank than the bank that buys the

bond, as shown in figure 44.6, in which case reserves are transferred to the

seller's bank which then creates the money to credit the seller's account. In

either case money has been created by the banking system, although the bond

buying bank might well not be the bank that creates it.

Figure 44.6: How the banking system creates the money to

buy government bonds on the secondary market.

However the banking system obtains government bonds,

either on the primary or secondary market, it has created the money to buy them.

As a result it gets interest from the taxpayer on a zero risk asset, the

taxpayer gets nothing in return, and at the same time the banking system is

able to increase its lending.

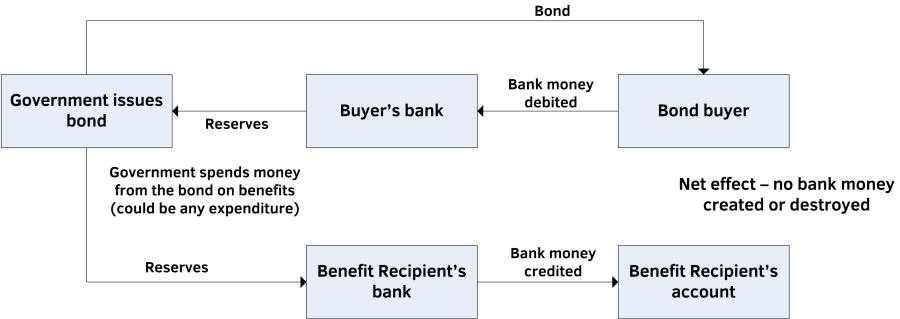

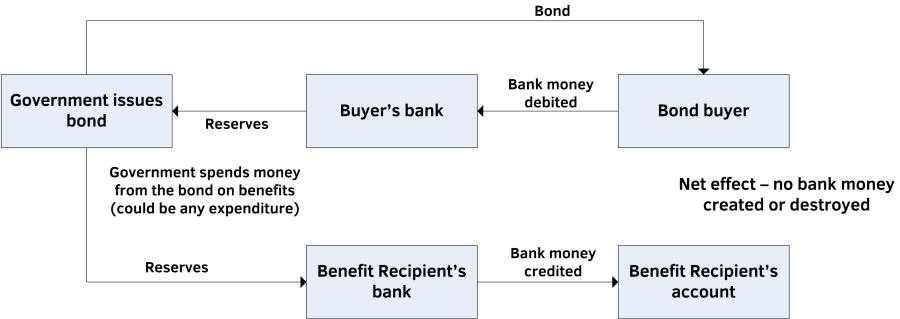

xv. A non-bank company buys a

bond on the primary market: the company pays money to the government and its

bank transfers the corresponding reserves. Bank money is destroyed in this

process, but is recreated when the government spends the money raised in the

economy. Hence there is no net effect on the money supply in this process. The

same applies if a non-bank company (or individual) buys a bond on the secondary

market. Here bank money merely changes hands and the bond also changes hands. See

figure 44.7.

Figure 44.7: If a non-bank company buys a bond on the

primary market then there is no effect on the money supply. The same applies if

it is bought on the secondary market.

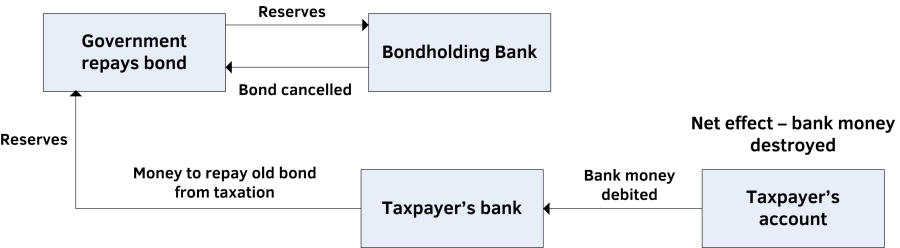

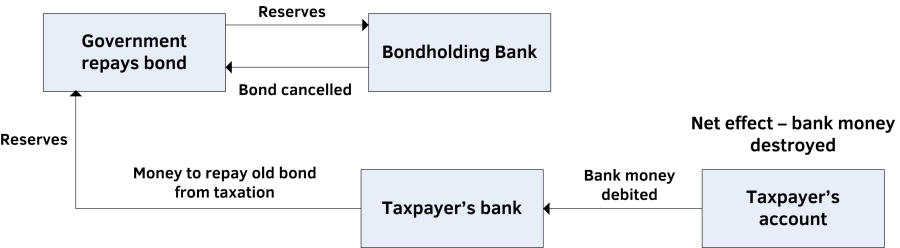

xvi. The government repays a

bond owned by a bank on maturity: the government transfers reserves to the

bank and the bond is cancelled. The bank's reserve account is debited (an asset

is created) and its bond account credited (an equivalent asset is destroyed). Hence

no bank money is involved directly, but in order to repay the bond the

government has to raise the money, either by issuing a new equivalent value

bond or by taxation. Figure 44.8 shows the effect if the money is raised from

taxation. Here bank money is destroyed because bank money is debited from the

taxpayers' account, but isn't credited anywhere else. If the money to repay the

bond is raised by issuing a new bond, then the overall effect depends on

whether it is bought by a bank or a non-bank. If bought by a bank then there is

no net change (no bank money is involved, reserves are transferred from the new

bond-buying bank to the government which transfers them to the bank holding the

maturing bond), and if bought by a non-bank then money is destroyed in the same

way as it is if taken from taxation.

Figure 44.8: Government repays a bond held by a bank from

taxation - bank money is destroyed.

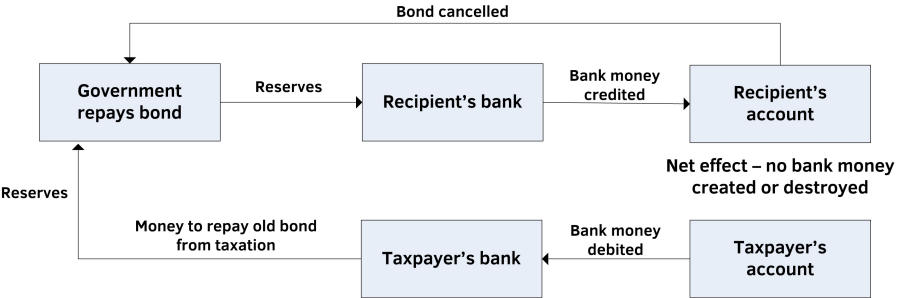

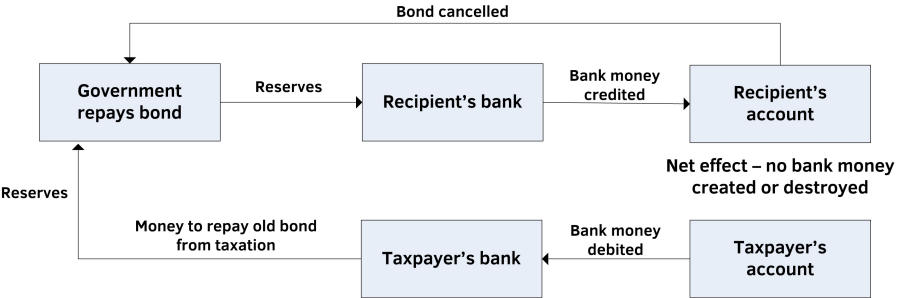

xvii. The government repays a

bond owned by someone other than a bank on maturity: the government cancels

the bond and transfers reserves to the bank of the bond owner which debits its

reserve account (an asset is created), and the bond owner's bank creates bank

money by crediting the bond owner's account (an equivalent liability is

created). Hence bank money has been created. However, again the government must

raise the money to repay the bond as above. Figure 44.9 shows the effect if the

money is raised from taxation. Here bank money is destroyed as before so there

is no net effect - bank money is created for the maturing bond holder and

destroyed for the taxpayer. If the money to repay the bond is raised by issuing

a new bond, then the same applies as discussed above - the overall effect being

to create money if it is bought by a bank but no effect if bought by a non-bank.

Figure 44.9: Government repays a bond held by a non-bank

from taxation. No bank money is created or destroyed.

Isn't it strange that the state refuses to create

money for itself, preferring instead to borrow money created out of thin air by

private companies, when taxpayers have to pay heavily for this 'service'? See

also chapter 89.

Although the mechanisms of bond sale and repayment when

banks are and are not involved are complex, the overall outcome is simple and

exactly the same as when a bank buys or sells any other type of debt other than

when dealing with another bank - banks don't create bank money for each other. The

point made earlier about new bank money coming into existence whenever a bank

makes a payment in bank money and going out of existence whenever a bank

receives payment in bank money can now be restated in terms of debts:

When a bank buys a debt from anyone other than another

bank, bank money is created and lasts as long as the debt lasts. When a bank

sells such a debt then bank money is destroyed. If any other person or

organisation buys or sells a debt then there is no net effect on bank money.

A bank buying a debt includes accepting a signed mortgage or

other form of loan agreement as well as buying a government bond, and selling a

debt includes a mortgage or other debt being paid off (in effect the bank sells

the original agreement back to the borrower in return for the repayment), and

in the case of a government bond the bank sells the maturing bond back to the

government in return for reserves.