A man walked into a bar & ordered a pint. The beer

cost £3 but the man had no money so he gave the barman an IOU.

A month later he returned and paid the barman £2.90.

"This is 10p short." said the barman.

"Not so," said the man. "I lent you an IOU

for a month so you owe me interest on it, I deducted 10p and now we're

straight."

"What?" said the barman, his face growing

increasingly purple. "You expect me to pay interest on an IOU? You cheeky

b-----d! You didn't lend me anything. I did the lending, I lent you a pint and

by rights I should charge you interest on that!"

"Not so," said the man. "I did indeed lend

you an IOU, just as banks lend IOUs all the time, and they charge interest

without anyone raising any objections. I'm merely adhering to standard banking

procedure."

The arguments set out here represent the solution to a

conundrum. Given that banks aren't deprived of anything when they credit

borrowers' accounts (because they create credit on the spot out of thin air - in

effect they issue IOUs - see chapter 39), and given that borrowers enjoy real

benefits when they buy things with the borrowed IOUs, who is deprived of the

things that benefit the borrowers? The things bought by borrowers certainly

don't materialise out of thin air like bank IOUs, so someone must have given

them up, but who? And did they receive any compensation for doing so?

I believe that the analysis presented here reveals an

enormous subsidy from society to banks that remains hidden because it represents

another outcome of the widespread belief that money is wealth (see chapter 1). It

adds very significantly to the existing well-known subsidies due to periodic

bailouts, deposit protection guarantees, and the cartel subsidy (caused by the difficulty

that would-be new entrants to banking face allowing charges to be higher than

they otherwise would be - see chapter 46).

Banks create new money by issuing IOUs in return for loan

agreements - they merely acknowledge that they owe a borrower a certain sum of money,

and the borrower is able to pass on that IOU to anyone else in the economy in

return for wealth. A bank IOU is merely an acknowledged debt, recorded in the

bank's computers, but a debt that can be spent as money because everyone trusts

the bank's ability to repay it in cash on demand. If cash consists of tokens,

then bank IOUs consist of promises to pay tokens. Not only do we believe that

tokens are wealth, we believe that promises to pay tokens are wealth too!

It should be stressed that banks are not deprived of

anything when they create bank money because the money didn't exist before the

borrower signed the loan agreement.

Let's work through the process of bank lending. Banks create

IOUs and lend them out as money for many purposes, then destroy them when they

are returned to the bank as a repaid debt. While the rate of creating new IOUs

exceeds the rate of destruction of old IOUs the quantity of money in the

economy expands, and when the rates are reversed it contracts. In a steady

state both rates are equal, and the quantity of money neither expands nor

contracts. The steady state provides a very useful starting point for analysis

because it allows us to remove money from consideration to show what happens to

wealth in isolation. We can then use the insights gained to consider the impact

of non-steady-state conditions.

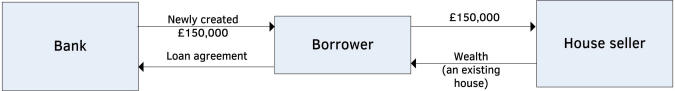

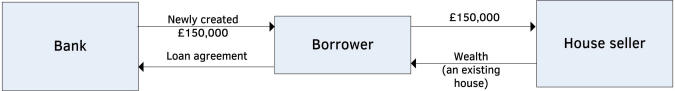

Consider a bank loan of £150,000 for a house purchase. The

bank creates the money in return for a loan agreement, and the borrower uses

the money to buy a house, as shown in Figure 48.1. For the duration of the loan

the borrower pays interest to the bank.

Figure 48.1

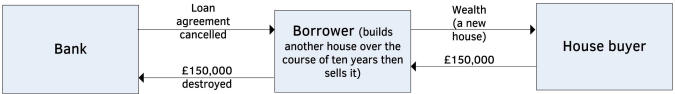

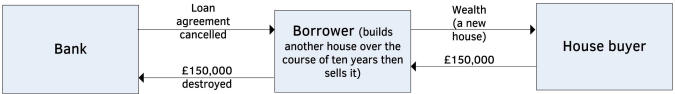

To keep it simple let's say that this is an interest-only

loan, where the borrower pays it back as a lump sum at the end of the term of

(say) ten years. In normal circumstances wealth in the form of labour is sold

continuously in return for money, which is saved or invested so as to repay the

loan at the end of the term. Here, instead of selling labour the borrower uses

it to build another house during the term and at the end sells it for £150,000.

This is done to keep the money-raising transaction simple - just one

transaction is required to raise the money to repay the loan rather than many

smaller transactions over a longer period of time, which wouldn't change the underlying

process but would make the illustration more complex.

The repayment transactions are shown in Figure 48.2. At the

end of the term the borrower has finished building the house and sells it,

using the money received to repay the bank which in return cancels the loan

agreement. In the diagram the loan agreement is shown as being returned to the

borrower, but in reality the bank merely notifies the borrower that it has been

repaid which amounts to the same thing.

Figure 48.2

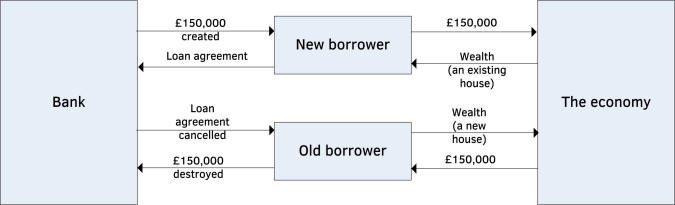

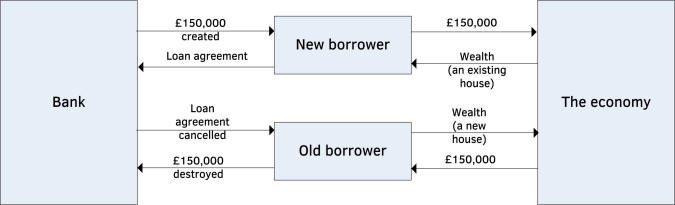

In order to see what is happening in terms of wealth

transfer as a result of all these transactions we need to arrange things so

that everything that isn't wealth can be removed from the picture, and to do

that we need to replicate a steady state on a small scale. We do so by combining

both the loan and the repayment in a single diagram, using an old borrower who

repays a loan at the same time as a new borrower takes out an equivalent new

loan. Additionally we can combine the house seller and house buyer into a

single entity which is the economy, since all wealth is both bought from and

sold back to the economy. This is shown in Figure 48.3.

Figure 48.3

Here, before any transactions take place, there is no money.

In the first transaction the new borrower asks for a loan, signs a loan

agreement and has his or her account credited with £150,000. In the second

transaction a house is bought from someone in the economy who has one to sell. At

this stage the money has merely passed through the hands of the new borrower in

its entirety. In the third transaction the same amount of money passes from a

house buyer in the economy to the old borrower, and in the fourth transaction

from the old borrower back to the bank. When the bank gets the money it is

destroyed, so after all four transactions once again there is no money. Money

has been created, passes through all participants in its entirety and is

finally destroyed. In relation to the effects of the transactions therefore we

can remove money altogether, because there is no net change with respect to

money. But that's not all. Before the transactions the bank had one loan

agreement for £150,000, and afterwards it again has one for the same amount, so

there is no change with respect to loan agreements and they too can be removed.

And even that isn't all. The bank itself is now divorced from all changes so it

can be removed as well.

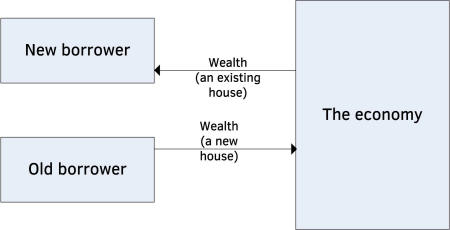

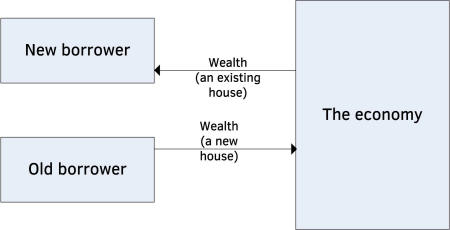

What we are left with is the wealth transfer diagram shown

in Figure 48.4. What was apparently complex is now seen to be very simple.

Figure 48.4

This shows that in a steady state wealth is taken from the

economy and transferred to new borrowers at the same rate as it is received by

the economy from old borrowers - but it is deprived of wealth for the duration

of every loan. The economy gives up something of substance - wealth - in return

for something of no substance - bank IOUs, and only gets that substance back at

the end of each loan term when it buys the wealth back, giving up bank IOUs in

return for wealth. The real lender therefore isn't the bank, which doesn't lend

anything of substance, it is the economy, or in other words, society, which

does.

But what happens when bank lending isn't in a steady state?

When the rate of bank lending is greater than the rate of repayment more bank

IOUs are being supplied by banks to the economy via new borrowers than are

being repaid from the economy to banks via old borrowers, so as the new

borrowers spend the IOUs they take wealth from society faster than old

borrowers supply it back to society, and the wealth depletion is replaced by

borrowed money in the form of bank IOUs, which increase within society as

wealth decreases. When the rates are reversed more wealth is supplied to

society from old borrowers than society supplies to new borrowers, and the

wealth increase is offset by a decrease in borrowed money in the economy in the

form of bank IOUs.

In all cases wealth has been supplied by society in

return for bank IOUs acting as money, so it is society that is deprived of

wealth as a result of banks' lending, whereas banks are deprived of nothing. It

is society that does the real lending. As long as we think that money and

wealth are equivalent we don't notice that anything has been lost.

Since it is society that does the real lending it is

entitled to compensation in the form of interest, but it gets nothing, banks

pocket the interest and no-one even notices the sleight of hand!

In spite of the above reasoning you might point out,

correctly, that banks and borrowers are part of society too, so where is the

injustice? The injustice is that banks represent only a very small segment of

society, but they receive the compensation that is due to the whole of society.

The borrowers are neither advantaged nor disadvantaged. Although they hold the

borrowed wealth they pay interest on the value of that wealth, but they pay it

to banks instead of to society, which is the rightful recipient.

The trick works because whenever a borrower buys something

it is an individual who receives the borrowed money, and to that individual

money and wealth are equivalent because they can spend it whenever they like so

they don't feel deprived. It is the economy as a whole that is deprived because

as was shown in chapter 1 money is not equivalent to wealth for the

economy. At any point in time an economy only has so much wealth available, and

that is all we have to play with, however we may buy and sell it between

ourselves.

When banks lend money and borrowers spend it no

individual seller of wealth feels disadvantaged, but the economy as a whole is

disadvantaged.

The 'point in time' qualification is very important, because

targeted spending of new money can bring new wealth into existence in the future,

provided that there is spare capacity available to create it - unemployed

people, idle tools, idle machinery and unused raw materials, and that feature

of money reinforces our belief that there is no deprivation. In fact that's why

banks like to think of themselves as 'wealth creators', and indeed why many

people think of them in that way too, and believe that banks are necessary for

that reason. What they all fail to acknowledge is that it is spare capacity

that creates wealth, not banks. What banks and new money do is to allow spare

capacity to become wealth production. Without spare capacity new money can't

bring more wealth into existence because the economy is already producing as

much as it can, all new money then does is cause inflation. Provided that spare

capacity exists new money will turn it into wealth wherever the money comes

from (see chapters 17 & 18).

Banks certainly aren't necessary in order to create money. The

Bank of England on behalf of society can create it just as easily, at practically

no cost, and free of interest-bearing debt (and does so in the case of notes,

coins and reserves). This money can then be handed to government to spend in

the normal way into the economy. In that way the benefits that arise from money

creation are enjoyed by society and not by private interests. Positive Money

has set out in detail how this could work in its book 'Modernising Money'(Jackson

& Dyson 2012).

At any time we can get an indication of the total value of

wealth that society has been deprived of, it is a significant proportion of the

total value of bank IOUs in the economy. Page 113 of Jackson & Dyson 2012

states: 'Between 1970 and 2012 banks increased the money supply from £25

billion to £2,050 billion - an 82 fold increase.' Therefore in 2012 society

had lent a significant proportion of £2 trillion worth of wealth without any

compensation! The amount of bank money not associated with lent wealth was

that used purely for financial transactions. Money used in financial

transactions and its impact on the economy is discussed in chapters 23 and 24

and in Werner 2012.

The value of wealth that you personally have

lent without compensation is a significant proportion of the bank money that

you have in your possession.

We should acknowledge that banks do provide a useful service

so they are entitled to be paid fees for that service (though the work involved

is only very loosely related to the size and duration of the loans and is

largely done by computers, so such fees should not be in the form of loan

interest), and they are also entitled to recover loan default costs because

they represent real risks to banks. A loan that isn't paid back leaves the bank

with a liability that it must meet from its own resources - see chapter 44. Default

costs are closely related to the size and duration of the loans so they should

be in the form of loan interest. What they are not entitled to is the opportunity

cost of the loans that they make. When something is lent by someone other

than a bank, the lender is deprived of its use for the duration of the loan. Its

use is handed over to the borrower until it is paid back. This applies to money

or anything else. In deciding to lend money the lender loses the opportunity to

spend it, and this lost opportunity is known as the opportunity cost of the

loan. The lender is therefore entitled to compensation by recovering the

opportunity cost from the borrower, who enjoys the opportunity to spend it in

place of the lender. In the case of bank lending the money didn't exist until

it was created in return for a loan agreement, so there was no opportunity for

the bank to do anything else with it. Positive Money has given an indication of

how big this benefit is to banks. It states that before the Bank of England

lowered interest rates in 2008 UK banks received just over £213 billion in

interest payments (Jackson & Dyson 2012 p156). From this we should deduct

the amount they pay out in interest on deposits, and also reasonable service and

default costs. The amount left is very substantial indeed and accounts for the

bulk of bank profits, exorbitant manager and director salaries and bonuses, and

staff costs for people not involved in servicing bank loans - loan service

costs are legitimate and recovered from the service fees. If society was to

receive the opportunity-cost interest as it should, then it is likely that it

would fund a very substantial proportion of the NHS. Note that this situation

only arises for banks. When non-bank lenders lend money the money has been

obtained by selling wealth, so society is not deprived of anything as a result

of the loan.

Let's say that inflation erodes the value of money by 50%

over the loan term. Apart from interest the borrower is only obliged to pay

back the original amount of the loan to the bank, regardless of what inflation

or deflation has done to its value in wealth terms in the meantime. If £150,000

is borrowed from the bank and a house is bought with that money, then at the

end of the term £150,000 is only worth half a house, so the borrower only has

to repay wealth to society to the value of half a house rather than a full

house, because half a house's worth of wealth can be sold at that time for £150,000,

which is what the borrower owes to the bank. Therefore it is wealth lenders -

society - rather than banks that lose out by inflation, because they only get

back a proportion of what they lent, in the above case only half. The

beneficiaries of their loss are borrowers, who gain substantially in wealth

without having to trade any wealth for it, which is clearly inappropriate.

Not only does society receive no compensation for

lending wealth when banks lend money, it also loses out to the extent of inflation

over the loan term.

Of course the opposite would occur if there was deflation,

but governments go to great lengths (for good reasons) to avoid deflation,

whereas they are content (also for good reasons) to allow low levels of

inflation, which over the course of loan terms - often 25 years or more - can

grow to very high levels. For example: 2% inflation for 25 years amounts to an

increase in price of 64%.

Preventing any private company from creating money would

ensure that lenders only lend pre-existing money, obtained by having sold

wealth to society, so society would no longer lose because of inflation. Of

course inflation might still cause lenders to lose and borrowers to gain, but

such risks are routinely taken into account in setting the terms of loan

contracts and society is not involved.

After all that you might still be inclined to say 'So what?

I thought it was the interest payer who provided banks' unearned income but now

I see that it's society. Banks still get something for nothing so what

difference does it make?'

The difference is that interest payers know what they have

to pay at the outset and consent to paying it. In fact borrowers normally

approach banks for money rather than the other way round. Banks don't normally

force anyone to borrow money. While private banking persists borrowers should

indeed pay interest, but to society, not to banks. Society on the other hand

does not consent to lending wealth without compensation. In effect it is

cheated out of its rightful due because of ignorance as to what is really

happening.

The fact that bank lending cheats society shows that

no amount of regulation tightening would leave society unharmed while banks are

able to lend IOUs and charge opportunity-cost interest. It might reduce the

risk of financial instability but it would do nothing to stop banks taking that

which belongs to society.

It is a difficult process to accept because it's so

counter-intuitive. It's one thing to accept that banks create rather than lend

money, but quite another to accept that wealth is lent, especially when the

lenders are given money and can spend it on whatever they want. No individual

is deprived of anything because they have money; it's society that

suffers the deprivation, though that's a difficult form of deprivation to pin

down conceptually. Therefore to show how it works a more localised example will

be used in which the mechanics of the process are worked through.

Consider a gardener who grows 40kg of potatoes for her

family each year. A newcomer comes along wanting a share of potatoes for his

family but without anything to trade for them. The gardener agrees to lend the

newcomer 20kg of potatoes on condition that he prepares some land and works

hard for a year and grows 60kg of cauliflowers, 20kg to repay the loan of

potatoes, 20kg for himself for the following year, and 20kg to exchange with

the gardener for potatoes for the following year. Thereafter they will each

grow 40kg of their own vegetables and exchange half with the other.

So far so good.

Now let's start again but this time the newcomer isn't

alone, a banker comes along too. The banker claims to have a very large stock

of gold coins safely locked away in a secure vault but in truth only has one. This

is the now familiar deception that banking is based on. Neither the gardener

nor the newcomer has any reason to disbelieve the claim because the banker is

clearly very wealthy and gives every impression of having a vast quantity of

gold. The banker explains that there is no need to borrow potatoes; instead he

will lend the newcomer enough money to buy the potatoes. The local community

uses gold coins as money, and one coin is worth 5kg potatoes. Instead of

lending coins the banker writes out and signs four elaborate tokens, each worth

one coin, explaining that these are more convenient than coins, but if required

he will be happy to exchange any for coins at any time - though he only has a

single gold coin and hopes that he will not be asked to exchange more than one

token, otherwise he will have to borrow the excess from other bankers and pay

interest on them, albeit at a much lower rate than he intends to charge the

newcomer. The tokens are lent to the newcomer on condition that he pays 25% in

interest to the banker after a year. The pair accept the banker's word about

the tokens and in return for the four tokens the newcomer receives 20kg

potatoes from the gardener.

The gardener has no need to exchange any tokens so at the

year-end she still has all four tokens. Note again that as before she is

deprived of 20kg of potatoes for the loan period, but this time she doesn't

realise it because she has money in the form of tokens.

At the end of the year, as before, the newcomer has grown

60kg of cauliflowers; 20kg to sell back to the gardener for four coins or

tokens, 20kg for his family for the following year, and 20kg to exchange for

potatoes for the following year. The gardener pays the newcomer for 20kg of

cauliflowers using the original four tokens, and the newcomer pays them back to

the banker plus a gold coin as interest.

To summarise, the essential points of the story are as

follows:

·

the gardener was deprived of real wealth (potatoes) for one year

without any compensation;

·

the banker was not deprived of any wealth at any time (all he

lent was paper);

·

the newcomer had to do extra work to earn the coin paid as

interest to the banker;

·

the banker gained gold to the value of one coin without having to

do any work;

·

in a fair world the gardener would be entitled to interest

because she was the one who was deprived for the duration of the loan and

deserved compensation for that deprivation.

·

In other words the banker took the interest that was due to the

gardener.

I believe that an examination of this question opens up the

possibility of a solution to many of the world's most pressing problems. The

deprivation suffered was at the level of society as a whole, and society didn't

even notice! The fact is that society not only has a vast store of existing

wealth ready to lend but also a vast store of spare capacity ready to be

released to create more wealth. All that is needed in either case is money -

mere tokens - and that's what banks provide. Let's just take away for a moment

the opportunity-cost interest that banks receive and consider what happens. Banks

make money available almost free of charge to anyone who is

creditworthy. In effect creditworthy people can have almost free money on

condition that they pay it back in due course.

Many of those borrowers buy existing wealth, and many of the sellers of that

wealth buy other existing wealth, but sooner or later much of the money will be

spent on the creation of new wealth, and use up spare capacity in doing so. As

has already been argued in chapter 22 spare capacity is waste - waste that we

didn't even recognise as such - so bank money allows us to avoid waste, and

that is a very good thing. Spare capacity is freely available for use, money

costs nothing, but together they create wealth. This brings us right back to

the insight that emerged in chapter 3 - Surplus wealth, specialisation and

trade are the basis of civilisation, and consist simply of people working in

co-operation to do and make things for others.

In effect we are able to turn tokens into wealth -

base metal into gold - we have realised the alchemist's dream!

There's one last mental step that we need to take and that's

to bypass banks altogether and have the state create money and use it to release

the wealth-creating ability of spare capacity. We can use that wealth for

ourselves or others, or, better still, both at the same time. Consider the BoE

giving newly created money - not lending it - to poor countries, on condition

that they spend it on UK wealth. They import UK goods and services that help

their country develop. The money that was given comes back to the UK, where it

creates employment and uses up spare capacity. The income multiplier (see

chapter 17) works its magic and the UK benefits enormously as well as the poor

country - as long as there is spare capacity to be absorbed.

If you are inclined to think that this can't possibly work -

and I wouldn't blame you because it really does seem too good to be true

- then we already have a shining example. It is exactly what the US did after

the Second World War in implementing the Marshall Plan. They gave us and other

war-torn countries free money, and both we and they benefited enormously -

because everyone had plenty of available spare capacity. Between us all we

turned US dollars into jobs, wealth and prosperity - magic! The Marshall Plan

is discussed further in chapter 67 subsection 67.2.1 - 'The Miraculous Power of

Gifts', and giving or lending money to poor countries is discussed in chapter

76 section 76.2. It seems like magic, but only because we don't recognise the

waste that spare capacity represents. Spare capacity is wealth that is freely

available. The capacity is already there, all it needs is to be released, and

all that takes is money - mere tokens - which are also freely available.

Of course it all has to stop when all the spare capacity has

been used up, because thereafter additional money just creates inflation. But

we have a great reservoir of spare capacity that we don't even recognise as

such. It is in redeploying all the wealth extractors and their employees as real

wealth creators, and redeploying all those whose efforts create bad wealth (see

chapter 7). Add to that the 5% acknowledged unemployed and massive underemployment

and we see that we aren't about to run out of spare capacity anytime soon. These

aspects are discussed further in chapter 100 sections 100.10 and 100.11.

A final word should be added about the pub story at the

beginning of the chapter. In it the person supplying the wealth (the barman)

pays interest on the IOU he received because the customer claimed that it was

borrowed by the barman. In making that claim he was overplaying the role of

lending. In fact the IOU was payment for goods received, and as such shouldn't

warrant the payment of interest. If instead a third person wrote out the IOU

for the man in return for a promise to repay, then that person, in applying

standard banking procedure, could charge the man interest on it. That would have

been more true to life but wouldn't have made as effective an illustration of

how inappropriate it is to charge interest on an IOU.