The Cost of the South and the Turk Stream

It must be also mentioned that the South Stream pipeline was announced in 2006. The economic climate of 2006 was very different from the economic climate of 2014. In 2006 it might have been possible for Russia to finance a 40 billion dollar pipeline, but this became much harder after the economic crisis of 2008 and especially after the economic sanctions that have been imposed on Russia in 2014. Moreover there is the issue of the falling oil prices that hurt the Russian economy which heavily depends on oil exports. The oil prices are falling because Saudi Arabia increased dramatically her production in order to hurt the Russian and Iranian economies, because the Russians and the Iranians are arming Assad in Syria. Both Russia and Iran depend on their oil exports.

At the following BBC article, titled 'Was Russia's South Stream too big a 'burden' to bear?', December 2014, you can read that the most plausible explanation for the cancellation of the South Stream is Russia's economic problems. According to BBC not only Russia is facing a severe economic crisis but she also needs 100 billion dollars to construct the natural gas pipeline of East Siberia, which will connect Russia and China.

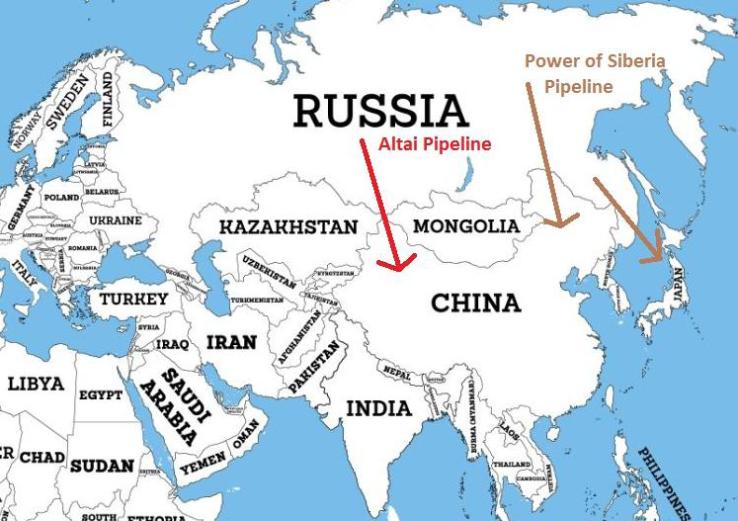

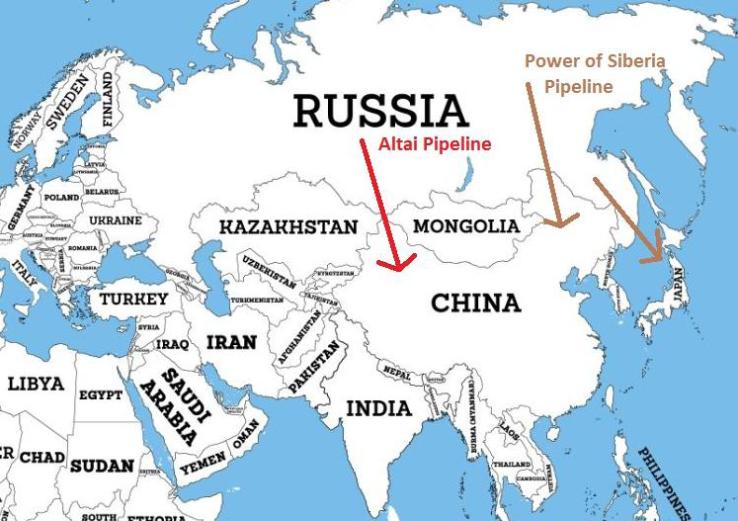

BBC is referring to the recent 400 billion dollar agreement between Russia and China, according to which Russia will start selling China 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas every year for the next 30 years. However for this agreement to materialize a modern pipeline network must be built, which will connect Russia and China, and that's what BBC is talking about. At the following rough map you can see the Altai Pipeline, which will connect Western Siberia and China, and the Power of Siberia Pipeline (POS), which will connect East Siberia and China.

Picture 52

3rd and 4th Paragraphs

'It may be a bluff,' said Martin Vladimirov, an energy specialist at the Centre for the Study of Democracy in Sofia, 'to pressurise the Bulgarian, Serbian, Hungarian and Austrian governments to unite behind accelerating the project, and make a better case for it to the European Commission'.

However, he favours a second explanation, that South Stream is 'simply too big a burden' amid the difficult financial situation facing Russia's state-owned giant Gazprom.

6th and 7th Paragraphs

Instead, Mr Vladimirov believes, Gazprom is looking to new markets, turning its gas strategy eastwards. 'It would need $100bn in the next four to five years to develop the Eastern Siberian fields and construct a pipeline to China,' he says. Scrapping South Stream comes as a setback to the governments in Hungary and Serbia, among the strongest backers of the project, alongside the Austrian company OMV and the Italian ENI.

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-30289412

Below you can see a rough map of Siberia. Siberia is the Russian territory that extends from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Picture 53

At the following Natural Gas Europe article, titled 'ENI may Cap South Stream Participation', November 2014, you can read that ENI, the Italian energy giant which held 20% of the shares of the South Stream project, announced that it would leave the South Stream project if the cost kept rising. Note that ENI's largest shareholder is the Italian government which holds 30% of ENI's shares. After the cancellation of the South Stream in December 2014, Russia bought the shares of the South Stream that were held by ENI, in order to compensate the company for its losses.

1st Paragraph

ENI has indicated that it may leave the Gazprom led South Stream gas pipeline project should the Italian state-controlled energy be required to commit greater financial resources that initially expected.

http://www.naturalgaseurope.com/eni-south-stream-financing

It is generally accepted that the South Stream was never an economic project. Russia and Europe needed the South Stream in order to overcome the crises in the Russian-Ukrainian relations which in the past have left many European countries without natural gas supplies. Russia also wanted the South Stream in order to make it harder for a competing pipeline to be built and compete with Gazprom in Europe. Therefore it is clear that the South Stream was a political and not an economic project.

At the following London School of Economics article, titled 'Who are the winners and losers from the cancellation of the South Stream pipeline', you can read that the South Stream was a political project, and its main purpose was to prevent the construction of Nabucco, and that the Turk Stream is also a political project, and its purpose is to prevent the construction of TANAP.

11th, 12th and 13th Paragraphs

At this stage, it is more difficult to tell whether Russia and the European Union will gain or lose from the cancellation of South Stream. As far as Russia is concerned, this may sound paradoxical, as the project was Moscow‘s brainchild. Gazprom has lost an opportunity to further strengthen its position in the EU energy market. However, from an economic viewpoint, the construction of South Stream made little sense at a time when European gas demand is dwindling and gas prices are low. South Stream was primarily a political project and had already achieved one of its key political aims: derailing the Nabucco project and perpetuating the European Union‘s dependence on Russian gas. Moreover, Putin‘s decision to shift gas exports toward Turkey may have a similar political function: a new Russia-Turkey pipeline may compete with TANAP and reduce its economic viability. To pursue this aim, Moscow has already put pressure on Turkmenistan not to supply TANAP (Azeri gas supplies are limited and Turkmeni gas would strengthen the economic rationale of the pipeline).

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/12/18/who-are-the-winners-and- losers-from-the-cancellation-of-the-southstream-pipeline/

Similarly to the South Stream and the Turk Stream pipelines, the pipelines supported by the US and EU are geopolitical projects too. That's the reason it was so difficult for Nabucco to come to life, even though it was supported by the EU and the US. Nabucco did not have much commercial rational, and that's also the reason TANAP faces so many difficulties. However TANAP makes more economic sense when compared to the South and the Turk Stream, because the countries of the Caspian and the Middle East are not connected to Europe through a pipeline network, while Russia is already very well connected to Europe through various pipeline networks.

But in a market economy, where geopolitics would not matter, and economic nationalism would not exist, the Caspian countries could send their natural gas to Europe through Russia. That would cost much less because Russia is already connected to Europe (see following map).

Picture 54

Unfortunately economic nationalism does not allow the market to take care of global energy. As long as this economic nationalism exists in the energy sector world wars will keep braking out. Anyway this is not an essay about economics but about geopolitics. I want to mention one more article from the New York Times, titled 'Russia Presses Ahead With Plan for Gas Pipeline to Turkey', January 2015. You can read that under the current financial conditions it makes sense for Russia to go for the Turk Stream, which will only cost 10 billion dollars, instead of the South Stream, which would cost 40 billion dollars. According to the New York Times Turkey is more interested on discounts for the natural gas that she already imports from Russia than on the Turk Stream.

13th and 14th Paragraphs

Energy economics played a role, too. The price of natural gas in Europe has dropped along with the cost of crude oil, and slow industrial demand is expected to mean sluggish growth for the European gas market. Russia‘s finances have been hit by falling oil prices. So a new pipeline estimated to cost as much as $40 billion to deliver gas mainly to small European countries like Hungary and Serbia made little sense. Industry analysts estimate that the cost of Turkish Stream would be about $10 billion for Gazprom, which so far has spent an estimated $4.7 billion on the Black Sea project.

20th Paragraph

To avoid wasting years of preparation and lengthy contract negotiations, Gazprom has quickly secured control of the Dutch company. In late December Gazprom said it was buying out its Western partners: Italy‘s oil giant, Eni; the French utility Électricité de France; and BASF‘s Wintershall oil and gas subsidiary. The companies said they would be compensated for their cash outlays so far, an estimated $750 million.

26th and 27th Paragraphs

Another potential sticking point is Turkey itself. For one thing, the country obtains about 60 percent of its gas from Russia, a dependence the government is not necessarily eager to increase.

Talks between Russian and Turkish officials on matters like the precise route and financial terms of a deal are said to be proceeding slowly. That is partly because the Turkish government appears to be trying to use Gazprom‘s need for a face-saving alternative to South Stream as leverage to negotiate lower prices for Russian gas, according to a Turkish official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the negotiations.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/22/business/international/russia-presses-ahead- with-plan-for-gas-pipeline-to-turkey.html