Step 1

Assess the Potential for Talks

By dint of their training and temperament, mediators like to mediate and negotiators like to negotiate, so it is hardly surprising that when confronted by a proscribed armed group they typical y contemplate the possibility of engaging that group in some form of dialogue. This inclination to talk can be a valuable counterweight to the equal y understandable instinct of most policymakers (and most people in general) to shun and isolate groups that use terror. By raising the notion of engaging proscribed groups, mediators and negotiators present policymakers with another option, one that may be unpalatable in several ways but that may also help the policymakers secure their long-term goals. But talking with terrorists is a dangerous and unpredictable game, and no one should contemplate playing it until they have thoroughly explored the potential of such talks.

Thus, the first question mediators—or negotiators and policymakers— should consider is whether engaging terrorists in some form of dialogue is likely to launch or advance a viable peace process, or impede or fatal y compromise an otherwise promising process, or lead nowhere at al . As they undertake this assessment, they must remember that the key consideration is the fate of the peace process (and the legitimacy of the wider political process) as a whole, not the fate of the proscribed group. For instance, initiating talks with a proscribed group may make the group’s wider constituency readier to contemplate a negotiated solution, but it may also enhance the proscribed group’s power and prestige and thus bolster its ability and incentive to obstruct any settlement that dilutes the proscribed group’s control over its constituency. By the same token, a 15 decision not to talk may keep the terrorists confined to the outer margins of mainstream political discourse, but it may also ensure that terrorist violence and the wider conflict endure for another generation.

In this first step, mediators must seek to determine the potential benefits and risks of talking; the nature of the terrorist group and the groups attitude toward talking; whether the timing is propitious for talks; and the likely impact of talking on other parties (including public opinion, moderates, and international actors).

Consider the Potential Benefits of Engaging

Although the mantric assertion of governments across the world— “We don’t negotiate with terrorists”—suggests otherwise, there can be a wide variety of advantages, both direct and indirect, to talking to proscribed groups.

Making the Terrorists Part of the Solution

The most obvious and profound benefit of talking to groups that use terror is to hasten an end to the violence and produce a sustainable peace. This involves the mediator turning the terrorists from being part of the problem into being part of the solution by involving them in the peace process. It is extremely hard to bring any peace process to a successful and sustainable conclusion without securing the participation of hard-liners—especial y hard-liners with no compunction about using violence—in that process. Not al hard-liners need to be brought into the process, but those who have the power to derail any negotiated agreement need to be made part of the dialogue if their opposition cannot be neutralized in some other fashion.

Weakening Support for Violence and Boosting Moderates

A second direct benefit is that the offer of talks may weaken support for violence not only within the PAG but also within its wider constituency (i.e., the ethnic, religious, political, or social group for whose benefit the PAG claims to be fighting). The prospect of negotiations may inspire moderates within the PAG to assert themselves and push the organization toward the bargaining table. And if negotiations actual y prove rewarding for the moderates (e.g., if the PAG secures concrete concessions, such as the release of its fighters held by the government), they may be able to keep their organization at the bargaining table, where the typical y slow and incremental process of exchanging the gun for the ballot box can begin to gain traction.

Even if this transition does not occur, the mediator can increase its influence on the conflict and/or the PAG by exercising those powers which almost any party acquires when it becomes a negotiating partner: namely, the powers to be heard and to listen, to help shape an agenda, to change perceptions, to confirm or confound prejudices, to elevate or undercut expectations, and so forth.

Conversely, not engaging may limit a government’s influence on a conflict, or even lead to the radicalization of a conflict if the refusal to negotiate empowers the most belligerent elements of a movement by showing that nonviolent means are not available. A refusal to talk may discourage new leaders who might otherwise have preferred peaceful means of change.

After winning the 2006 Palestinian elections, a number of moderates within Hamas sent conciliatory signals to the Quartet (the United States, the European Union, the United Nations, and Russia) indicating that Hamas was prepared to go part of the way to meeting the Quartet’s requirements for recognition. The Quartet, however, insisted that all its conditions be met. Once it became apparent that the international community was not going to lift the economic embargo on the new government, Hamas’s moderates seemed to lose influence to hard-liners within the organization.

While groups that use terror often do not make the successful transition to political parties, even a failed dialogue will introduce a movement and organization to the politics of the larger world, and make clear to terrorist leaders that there are rewards for engagement.

Redirecting the Terrorists’ Attention

A third benefit of talking is that while the talks may not lead to a negotiated settlement, the negotiations themselves may come to occupy a significant share of the PAG’s attention and energy, thereby reducing the PAG’s ability and incentive to mount a sustained campaign of high-level violence. A recent study found that about half of terrorist groups involved in negotiations continued to use violence, but the intensity and frequency of the violence declined as talks dragged on.8

The quotidian routine of negotiations may not produce any remarkable breakthroughs, but it can save lives. “Even if it does not result in a resolution to the conflict, engagement can save lives by mitigating the impact of violence on populations. The LTTE cease-fire in Sri Lanka, negotiated through the Norwegian channel, is a case in point. Even low-level engagement can be valuable because it al ows for a presence in the conflict zone that can monitor humanitarian conditions. In Sri Lanka after 2006, the lack of any engagement led to the absence of any human rights monitoring presence.” 9

Acquiring Intelligence

The longer that talks go on, the greater the useful intelligence that mediators and negotiators can acquire. Talking is a good way to find out more about the terrorists’ goals, priorities, and sensitivities—all of which can easily be missed or misconstrued when a group is demonized and isolated. During negotiations with the Provisional IRA and wider nationalist community in Northern Ireland, the British government learned that removing monarchical symbols (such as changing the name of the Royal Ulster Constabulary to the Police Service of Northern Ireland) won them unexpected points with Irish nationalists.

Useful intelligence can also be gleaned about the internal dynamics of the PAG, including the interplay, rivalries, and shifting balances of power among the group’s leadership. Years of negotiations with Palestinian leaders gave the United States a wealth of information about the relative weight of different officials within the PLO. Intelligence rewards may grow even larger if moderate constituents linked to a group can be wooed. The Italian Communists provided vital intel igence in helping the Italian government crush the Red Brigades, as the two organizations had overlapping constituencies.

Enhancing One’s Standing with External Actors

Engagement with a PAG may be valuable for maintaining good relations with a range of external actors, including key allies sympathetic to the terrorists’ political goals, even if there is little hope of the engagement generating a negotiated solution. By announcing that he or she is prepared to talk to the terrorists, the mediator or negotiator can display in a very public fashion that he or she is ready to do whatever it takes to bring peace. And should the PAG resist the mediator’s overtures, the PAG is likely to be seen in a negative light by international opinion, including the opinion of states and diasporas on which the PAG may depend for political, financial, diplomatic, and/or material support.

Recognize the Potential Dangers of Engaging

Despite these potential benefits, talking to groups that use terror has many risks, ranging from political embarrassment to encouraging more violence and even strengthening the group’s capacity for bloodshed. Not surprisingly, these concerns make officials leery of even considering the prospects of negotiations with terrorist groups.

Rewarding Terrorism

The most commonly cited objection to talks with terrorists is that any recognition of a terrorist group—and talks certainly constitute a form of recognition—rewards the use of terrorism. Most terrorist groups crave legitimacy, as their very tactics lead them to be shunned by the world and by many would-be constituents. Even if talks involve no concessions on the part of a government, by recognizing terrorists as worthy interlocutors the government gives them a victory with potential followers and other states. Other terrorists and would-be terrorists may believe that continued or even increased violence may lead to eventual recognition. The danger that engagement may convince observers that terrorism “works” is particularly damaging to governments seeking to discredit the legitimacy of terrorism general y as well as to oppose particular terrorist groups.

Weakening the Stigma of Terrorism

Talks with terrorists may also diminish the stigma of international terrorist listings such as the U.S. State Department’s list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs), the European Union’s list of terrorist individuals and organizations, and India’s Ministry of Home Affairs’ schedule of “Banned Organizations.” In addition to the legal implications of negotiating with a person or organization named on such lists, the lists themselves were established to anathematize terrorist organizations.

Moreover, such listings provide a focal point for international cooperation against terrorist groups. A government or international organization that opts to talk to an entity on one of these lists may weaken the moral sanction of any listing and may encourage other states to make other exceptions, further hindering future cooperation.

However, mediators and negotiators should assess the options for designating terrorist organizations to identify any ways of using the proscription process to incentivize an engagement process. When it began to engage the Maoists after their victory in elections in Nepal in 2008, the U.S. State Department for the first time said that Nepal’s Maoist party was on the “terrorist exclusion list” but was not formal y designated as a “foreign terrorist organization.” This subtle distinction was interpreted by observers as a sign of the U.S. government seeking to encourage the Maoists on their path of political reintegration.10

Undermining One’s Own Standing

Paying the price of recognition might be worthwhile if there was a guarantee of success in the end. But few talks with terrorists produce clear-cut gains and fewer still yield peace agreements. The conditions for ending long-standing conflicts are often difficult or impossible to meet, and terrorism, in particular, needs only a small group of people to continue. Putting a mediator’s or government’s credibility on the line, both at home and overseas, is thus risky, particularly as it may be at the mercy of a small group of diehard killers.

When talks fail, those who advocated them risk looking naïve, unwise, or worse—accomplices, albeit unwitting, of a terrorist group that thrives on public attention and official recognition. The backlash from both domestic constituencies and international actors can fatal y affect a mediator’s effectiveness.

Even success, if and when it comes, often is incremental rather than complete: a challenge that increases the political price of talks. Some groups may accept a cease-fire or other conditions for talks but engage in activities that suggest a change of heart remains far off. When the IRA accepted a cease-fire in September 1994, it kept its cell structure and logistics network and continued such brutal behavior as beating supposed col aborators and criminals with iron bars. Even after talks had progressed for several years, it made no effort to shut down its infrastructure of cel s or decommission any weapons, including its stockpiles of Semtex and mortars.

Undercutting Moderates

If mediators and negotiators who support engagement risk looking foolish when talks lead nowhere, the moderates within a PAG who championed the idea of talking risk being sidelined within or sanctioned by their organization, or even murdered by their harder-line colleagues. When talks lead nowhere, the door opens for hard-liners to assume or reassume control of policy within the PAG. Greater violence is usual y the result.

Talks with the United Kingdom in the early 1970s discredited older members of the IRA and led to the rise of a younger, more radical cadre who continued violence with little progress for over twenty years. The roots of the rise of Hamas and its ability to oust the PLO from power in the Gaza Strip lie in the failure to implement the Oslo Accords, which the PLO had negotiated but which Hamas had always opposed.

Creating Splinter Movements

But while deadlock is often costly, progress in the talks can be equal y or even more damaging in cases where the internal coherence of the PAG is weak. Those negotiating for the PAG may have control over or the support of most members of their group, but the closer a negotiated settlement comes, the more likely it is that a splinter group opposed to the making of any concessions will break off and create a yet more violent terrorist entity. In other cases, the PAG negotiators do not even control the majority of the group’s members and cannot deliver their acceptance of any negotiated agreement, so any concessions granted in exchange for talks become worthless.

Giving Terrorists Breathing Space

Some terrorist groups may enter talks and even proclaim a cease-fire with no intention of permanently renouncing violence. Because terrorist groups grow stronger by demonstrating their staying power, simply buying time in the face of an aggressive government counterterrorism campaign can be immensely valuable to them.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam repeatedly used cease-fires to rearm and regroup for their next offensive. In 1998 the Basque separatist movement ETA announced a cease-fire because of outrage—including among its own constituents—at ETA’s murder of a local politician. When ETA broke the cease-fire in 2000, its leaders claimed it had been a tactical trick to counter Spanish and French pressure. What ETA had wanted was not a peace process but a chance to work with and radicalize constitutional Basque nationalists. When the nationalist front failed to win substantial electoral support among Basque citizens, ETA resumed its terrorist activities.11

Some organizations raise money or otherwise develop their institutional capacity during a lull. Gerry Adams, one of the leaders of Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA, raised $1 mil ion in a trip to the United States in 1995, money that helped sustain the organization’s capacity for violence.

* * * *

Assessing the potential advantages and disadvantages of talking with terrorists is essential, but what does one do with the knowledge acquired during such an assessment? How, in other words, does one balance benefits and risks? The answer is twofold. First, evaluate the risks and benefits in relation to the specific characteristics of the terrorist movement one is confronting. Second, set the benefits and risks within the broader context of the conflict. The remainder of this chapter discusses what to look for in terms of both specific features and the broader context.

Assess the Willingness and Capability of the PAG to Negotiate a Deal

A thorough analysis of a movement’s goals, history, leadership, and constituencies is essential to determining its willingness and capability to engage in dialogue. If it leads to a conclusion that talks are possible and desirable, this assessment should also be used to build the foundation of a strategy for talking.

Evaluate the Terrorists’ Goals and Ideology

Can the PAG’s aims (e.g., changes to a political system, territorial ambitions) be achieved through negotiation or is the group fundamental y nihilistic or absolutist (e.g., it will settle for nothing less than the destruction or total capitulation of its enemies)? An unambiguous answer to this question may by itself dictate the mediator’s or negotiator’s decision to talk or not. After al , a group committed to the total eradication of a political system (e.g., al-Qaeda with its avowed goal of replacing nation-states in the Muslim world with a new Islamic caliphate free of any external influence) has in effect nothing to discuss with the supporters of that political system.

However, even many seeming absolutists are prepared to negotiate sometimes on some issues. Some absolutists may be “total” and others “conditional,” that is, while their purposes are beyond immediate negotiation and often millennial, some are beyond contact and communication whereas others may be, or become, open to some discussion and eventual y moderation of their means and even their ends. Attempts to deal with “total absolutists” are pointless, but efforts to identify potential “conditional absolutists” are not, especial y if they can be encouraged to see the hopelessness of their situation and the potential hopefulness in responding to negotiations.

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Northern Uganda is “the archetype of an irrational organization, with a radical theocratic ideology and extremely brutal methods of rebel ion,” but it is nonetheless “amenable to moderation through political bargaining—that is, in exchange for a deal at the International Criminal Court, which has indicted its top leaders.”12 Even though the LRA has been declared a terrorist organization by the U.S. government, the U.S. State Department decided to accept an invitation to become an official observer at peace talks involving the LRA, in hopes that the talks would result in the dissolution of the LRA.13

A distinction also needs to be made between the terrorists themselves (those who carry out attacks) and their operatives or organizers. The organizers do not blow themselves up. They are usually highly rational and strategic calculators. That is not to say they are necessarily interested in negotiating: their goals may be too extreme and they may regard negotiation and the compromises involved in it as anathematic and counterproductive to their strategy of asymmetrical warfare. But some of the organizers who dispatch suicide bombers are not so averse to talking.

When assessing goals and ideology, consider whether the movement adheres to a broad program of written principles and how important its foundational documents are to its political program. Not all terrorist movements have adopted a set of written principles or a political manifesto; and the absence of such a document usual y reflects the undemocratic nature of an organization or its lack of mass appeal.

But many terrorist movements or organizations do adhere to a set of political principles designed to attract fol owers. The publication of such a document, however, is not always indicative of its desire for political accommodation, or minimal y, its wil ingness to engage in a dialogue. A close study of a terrorist movement’s founding document—as wel as an investigation of how it was written and by whom—can provide substantive clues on its political goals. Conversely, movements may claim that their founding charters are no longer relevant or that they are wil ing to modify the radicalism contained therein. Some such claims do indeed attest to a significant shift in a PAG’s political goals, but other claims may be little more than negotiating ploys.

Considerable controversy has surrounded the issue of amending the Palestinian National Charter—the constitution of the PLO—which, inter alia, denies Israel’s right to exist. At various times since 1998 the PLO’s leadership has claimed that clauses within the charter have been nul ified or abrogated to meet American and Israeli demands. Other parties have not been convinced by these assertions. Former CIA Director James Woolsey has said: “Arafat has been like Lucy with the football, treating the rest of the world as Charlie Brown. He and the PNC keep tel ing everyone they’ve changed the charter, without actual y changing it.”

A PAG’s political strategy, as well as its principles, should also be assessed. The latter may indicate a philosophical embrace of inclusiveness but the former may point out that such inclusiveness is more rhetorical than actual. For instance, a mediator may conclude that it is not worth the effort of engaging a group that extols democracy in the abstract but whose strategy suggests that in practice, were it ever to win elections, it would promptly abandon further elections.

A mediator should also consider non-ideological goals. Movements associated with criminal activities such as narcotrafficking and smuggling may have little to gain from a diplomatic settlement because their il egal activities would be prohibited by a functioning system. However, in cases where their business is not incompatible with rule of law, it might be possible to co-opt or reach an accommodation with movements that have their eye on the bottom line rather than those driven by political grievances.

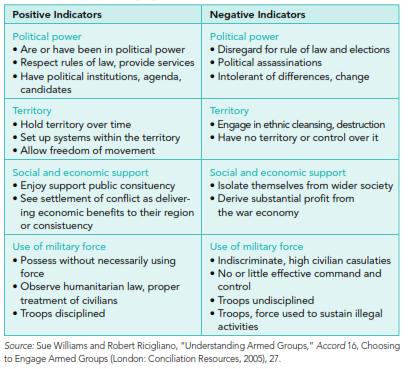

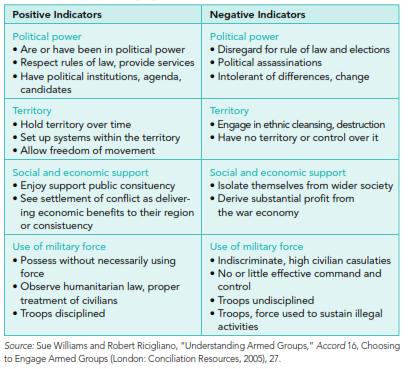

Figure 1 reproduces a chart, published by Conciliation Resources, of some of the other non-ideological indicators of a PAG’s readiness to engage in a peace process.

Figure 1. Indicators Regarding Opportunities for and Constraints on Armed Groups’ Engagement

Assess the Terrorists’ Constituency

Does the movement or organization have a constituency? What specific constituencies does a movement represent? Where are they located? How strong is their influence on a movement’s leadership?

These may well be among the most important questions that can be answered by the mediator or negotiator. If a terrorist movement or organization has no constituency, then it is likely to be less amenable to compromise and less vulnerable to popular pressure. Its leadership is likely to be self-selected, its claim to legitimacy less certain. It will be unable to answer the most obvious political question posed to any movement, organization, or party: Whom do you represent?

How the movement is funded can say a lot about whether it truly represents a wider constituency, one whose interests must be reflected in the peace process if sustainable peace is ever to be achieved. A movement or organization funded through criminal activities—counterfeiting, fraud, drug running and the like—may wel have only a small constituency and may wel oppose any peace process that threatens to crack down on organized crime. In general, the more diverse the funding base of a movement, the more diverse its constituency. A movement or organization funded through money raised from a broad diaspora constituency, for instance, usual y reflects the existence of broad support for its political agenda.

Assess the Group’s Leadership and Discipline

A failure to understand a movement’s leadership can lead to fundamental misunderstandings of that movement’s mindset. During an exchange between a retired senior American official and the leaders of Hamas in Damascus, the American was surprised to learn that not only were none of the movement’s most senior leaders religious, but nearly all of them held doctorates in the sciences.

To avoid such misapprehensions—and the strategic miscalculations they can inspire—the mediator should not only research the backgrounds and beliefs of a PAG’s leaders but also assess how an organization’s decisions are made: Is the movement or organization’s leadership elected or appointed, and by whom? Is a movement’s decision-making process democratic, consensual, or driven by a single leader? Is the movement’s leadership educated, is it religious, or did it arise as a result of a fight among factions?

A deeply rooted organization—one that is not simply a network like al- Qaeda—will have a complex leadership structure with a wide diversity of voices, experiences, and backgrounds. In general, the more complex the leadership, the more deliberate and careful their dialogue will be and the more thought-through their political positions. An organiation, incapable of making fast and unambiguous decisions on political questions, should not be considered negatively. Rather, it should be seen as a movement whose leadership is capable of intensive and careful debate and, hence, making the transition from revolutionary movement to political party. A self-appointed leadership can make decisions quickly, but without any broad support. An elected leadership cannot.

Determine how much control the leadership has over the movement as a whole and over rivals within it. Can the leadership impose a shift to negotiations and deliver the movement’s acceptance of any agreement? Can a movement control its most radical elements? Hizbal ah proved able to shut down radicals on its flanks who chal enged it to continue more revolutionary policies in the mid-1990s.

Even when a leadership favors negotiations and can corral its hard- liners, it can only become an effective negotiating partner if it also has the necessary resources (e.g., funds with which to finance the cost of transporting its representatives to negotiations and accommodating them comfortably and securely) and expertise (e.g., in formulating coherent negotiating positions and responding to the other side’s proposals).

Some leaders are willing and able to shift their organization from war to peace; others are locked, psychological y and/or political y, into an antagonistic, distrustful, zero-sum mind-set. Yasser Arafat found it exceedingly difficult to make the transition. Even after more than six years of direct negotiations with Israel, at the Camp David II negotiations in July 2000 commentators noted Arafat’s “isolation and deepening sense of being pressured by sinister Israeli-U.S. col usion, and his refusal to accept what were in his eyes insulting terms that did not go far enough in fulfil ing Palestinian aspirations but yet engendered his own personal standing in the Arab and Muslim worlds.”14 Nelson Mandela, in contrast, had firm control of the ANC and was wil ing to reach out to white moderates, averting the massive bloodshed and migration that characterized many African transfers of power.

When leaders resist the idea of talking, see if the lower ranks are more amenable. Top-level leaders may be too ideological y inflexible to make negotiation a productive possibility, but their lieutenants and followers are unlikely to form a monolithic bloc and may be more open to the idea of talking. It is almost always worth exploring the various levels of leadership to find people who are disil usioned with the group’s cause, tired of the conflict, or simply ambitious and ready to negotiate if it will advance their standing within the group.

Assess Attitudes