7 The Economics of the Commons

‘An economist is a man who states the obvious in terms of the incomprehensible.’

- Alfred K. Knopf

‘If all economists were laid end to end, they would not reach a conclusion.’

- Variously attributed

‘History teaches us that men and nations behave wisely once they have exhausted all other possibilities.’

- Abba Eban

‘Capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but… in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable.’

- John Maynard Keynes — ‘The End of Laissez-Faire’.

I started the car one day and a strange clanking noise came from under the bonnet. To make matters worse, it was a foggy morning and I could barely see past my fluffy dice. Probably I should have stopped the car right away and phoned for help, but instead I managed to drive it a short distance to a nearby repair shop. They checked it over and told me that it would be later that day before parts could be obtained and the car back on the road. The office I was renting was some way off and complicated to reach by public transport, plus get back in time to collect the car before the shop closed up. Then I remembered that two artist friends were hosting a lunch in Dundee that day. It was a ‘free lunch’ in a way, but there was something expected from the diners in return — as is the way with free lunches. The task was to complete a questionnaire contrasting emotional and financial economies. I went into Dundee for the lunch.

I took the questionnaire home and became increasingly intrigued. In the end I wrote eight pages in response and took part in a follow-up meeting. This was a little while before the Commons Group got going — but the two artists involved later joined that group, so in a way their free lunch project was preparing the ground.

Despite my best efforts to understand, it was only at a subsequent Commons Group picnic that I got the message that perhaps had been the artists’ intention in the first place. The message? Compassion is the currency of the emotional economy. That thought, in turn, leads to a more general realisation — an economy is a ‘social construct’ — a way of perceiving the world. Other ways to see the world, other economies, are always there, waiting to be seen and explored. Contrary to the way the world is so often seen today, the social always takes precedence over the economic.

Compassion, as the currency of the emotional economy, might seem a bit of an obscure point — but it is that odd little phrase that is really the theme of this whole book. Was it worth the free lunch? Well…

The preceding three chapters have looked at polity and the various options that we have for governing ourselves. We focused in on deliberative democracy in particular — giving everyone a voice — and in so doing, tried to answer one of the questions from the Introduction — Who Decides? We’ve looked at the material economy in an earlier chapter, and in our chapter on the commons, fitted this into a view of nature, and seen the parallels between it and a further economy — the cultural economy of imagination and creativity. In this chapter we will explore two further economies, and fit them together with the material and the cultural so as to see the full composition of societies. As we bring in the ideas about ownership, sharing and the commons, we will try to relate these to this larger view of society. This in turn will allow us to revisit some of the other questions from the Introduction, What do we own? What should we share? What should we make? How should we trade? We will try to get some tentative answers to these questions, before moving on to that wider question of: How should we live? in the next four chapters.

As with Chapter 2, Gandhi’s sin of Wealth without Work is worth keeping in mind for this chapter. His further sin of Commerce without Morality is also relevant.

In our exploration of the commons in Chapter 3, we mentioned that a whole further area of explanation is missing, and it was labelled simply as ‘re-making’. That re-making part is what the two artists in our story above were driving at. Re-making is the social commons and the emotional economy, and this chapter seeks to explore its importance to us and how we might bring it to light.

The Economic Base of Society?

We have seen that it is often the material economy that is regarded as of prime importance in society, especially societies of the developed world. When people speak of ‘the economy’ it is usually just to the material economy of goods and services they are referring. Culture, nature, and the commons are all peripheral, for the most part. Or where they are included, there might be an attempt to fit them into the economic model that defines industrial manufacture — such as ‘creative industries’ — or viewing nature as providing ‘environmental services’. We looked at the parallels back in Chapter 3, and especially in Figure 3.3. Whilst economics includes various schools of thought on these matters, they mostly agree that the big factors in a society circle around labour, production, trade and consumption. Ha-Joon Chang summarises the situation neatly. He says:

‘Every society is seen as being built on an economic base, or mode of production. This base is made up of the forces of production (technologies, machines, human skill) and the relations of production (property rights, employment relationship, division of labour). Upon this base is the super-structure, which comprises culture, politics and other aspects of human life, which in turn affect the way the economy is run.’

In earlier chapters I have tried to give a description of this process, seeking mainly to point out the deep reliance on nature and our view of nature, as well as trying to relate things to our understanding of the commons. There are elements neglected or under-emphasised in economics’ description of the material economy, but I am not in any way questioning the basic legitimacy of the description. What this chapter is questioning however, is the idea that the material economy is all that matters — the claim that it is the base of society from which all else is derived.

The True Base of Society

As the narrative describes at the head of this chapter, that the material economy — material wealth and capital — are not the true base of society. Instead I am suggesting it is the social relations that determine the economic relations of a society. We can therefore introduce a further type of commons, mentioned briefly in Chapter 3, but kept back until now — the ‘social commons’, and with that, what has been described as the ‘emotional economy’, compassion, and what I have covered, for now, by the term ‘re-making’. Massimo d’Angelis (Omnia Sunt Communia) describes all this simply as ‘commoning’. Others refer to the ‘informal economy’, or what Ivan Illich refers to as the ‘shadow economy’ — or sometimes it is just called the ‘love economy’. (See Hildur Jackson — Designing your Local Economy in Gaian Economics — Living Well within Planetary Limits.) Labour, production, trade and consumption are the ‘formal relations’ within society. The suggestion is that these formal relations are ultimately based on the social relations — the social commons. Jeremy Rifkin tells us:

‘Without culture it would be impossible to engage in either commerce and trade or governance. The other two sectors require a continuous infusion of social trust to function. Indeed, the market and government sectors feed off social trust and weaken or collapse if it is withdrawn. That’s why there are no examples in history in which either markets or governments preceded culture or exist in its absence. Markets and governments are extensions of culture and never the reverse. They have always been and always will be secondary rather than primary institutions in the affairs of humanity because culture creates the empathic cloak of sociability that allows people to confidently engage each other either in the marketplace or the government sphere.’ Jeremy Rifkin — The Empathic Civilization.1 Meanwhile, Arturo Escobar tells us: ‘Of crucial importance … is the recognition that the base of biological existence is the act of emotioning, and that social coexistence is based on love, prior to any mode of appropriation and conflict that might set in. Patriarchal modern societies fail to realise that it is emotioning that constitutes human history, not reason or the economy, because it is our desires that determine the kinds of worlds we create.’ (Arturo Escobar — Designs for the Pluriverse. My emphases.)

As we’ve seen above, there are numerous terms we could use to describe the emotional economy. One of the terms I have favoured in this book is ‘re-making’. Why re-making? One reason is the link back to the problems inherent in the consumer capitalist society we have created. The way things are produced has alienated us from our making. To work with our hands, to be meaningfully engaged with what we do and to relate to others through our work — these things are the basis of genuine making. And there is a natural affinity between making and re-making, where re-making is the repair and maintenance of our material existence, but also the ‘repair and maintenance’, care and sustenance, of our own bodies and our relationships with others and with the natural world. The other reason for the use of the word re-making is our alienation from the feminine aspect of life. Just as we are separated from our making, we are also separated from the fact that we are made — and made by women. Likewise, it is women who do most of the re-making in our societies. So re-making is quite a deep concept — telling us about our needs for connection to our own natures, to Mother Nature and to the cosmos.

There is still some social relations involved in the material economy, for instance, the relationship of workers to their employers, businesses to their customers and suppliers, and employees with other members of staff. Indeed, it is these elements that were of key importance to Marx, so it is not fair to say that social relations are entirely irrelevant to economics as things stand now. For Marx and Engels, it seems to have been a bit of both the formal relations and the social relations. But, as the structure (ie. the economics) came to dominate, and continues to dominate, so it is that ‘economic thought’ (accountants’ truth!) is applied to more and more areas of human endeavour. The structure dominates, the super-structure is ignored or even swallowed up. A better way to describe this would be to say that it is only the purely formal, material and financial transactions that are taken account of in the material economy. (We might add that the relations, as well as being transactional, may also be exploitative, patronising and instrumental.) The rest is downplayed or ignored. It is the recognition of the critical importance of the ‘emotional economy’ — especially those neglected aspects of ‘maintenance’, and often trivialised factors of creativity — that are important for a new story. The United Nations High Commission for Human Rights estimates that if, for instance, household labour were accounted for in our economies, it would represent between 10 and 39% of GDP. ‘To ask for capitalism to pay for care is to call for the end to capitalism.’ (Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things.)

If economics — and especially, the material economy — were really the driving force of society, then changing economics would change culture. But instead the suggestion is that if social relations were to change then economics would follow.2 Capitalism would morph into a new model. That key dichotomy that we have met in previous chapters — whether we need to change people or change our environment and structures — is therefore back with us in another form. If the social commons is really the driving force of society, and we feel that society needs improving, then we need to look, at least, at how culture might change in order to improve. And in looking at how we might change culture we may have to look at what we are like as individuals, and how we, in turn, may need to change.

Let’s continue our discussions by looking at what we neglect when focusing only on the material economy.

What we Neglect — Wild Nature and the Emotional Economy

Back in Chapter 3, I suggested that we needed to split our view of nature to include what we need to provide for ourselves as natural resources and what we choose to preserve, untouched, as wild nature. Wild nature, I suggested, is preserved for its own sake, as well as for the sake of the flora and fauna and the more abstract values of human flourishing. I related this split back to garden and wilderness, the reader may remember. We humans need to tend our gardens and leave the wilderness to do what it will. With regard to wild nature, we make two errors. Sometimes, we try to take all of it as resources — make it all garden — and don’t leave enough for the remainder of Earth’s inhabitants to live their lives. The other way we neglect wild nature is to disregard its importance for keeping everything going. Although looking at the commons has helped us in our understanding of our relationship with nature we can still end up just seeing the commons as another way of describing natural resources. So we need to broaden the idea of the commons — beyond just seeing them only as shared resources. As described by Massimo d’Angelis (Omnia Sunt Communia) the commons is also its social relations and our acts of commoning.

This leads to our other area of neglect — the whole area of compassion. Compassion sits outside the material and cultural economies, but plays a vital role in their continued functioning. I’ve taken up the terms from Charles Eisenstein (Sacred Economics) and from other authors in referring to the role of compassion and caring as the social commons, the emotional economy and re-making. In a sense, the material economy treats both wild nature and the social commons as ‘positive externalities’ — in other words, things provided for free by the wider environment, that material and cultural industries rely on in their production processes. The terms, emotional economy, social commons, and indeed, social capital, are not ideal descriptions. For one thing, as we discussed above, there is still an element of the social involved with material capital. For another thing, re-making covers a wide range of activities, from maintenance and reproduction, through to conviviality, friendship, relationships, intimacy and love, so describing this as an economy or as capital is a bit strange. Maybe, even those mundane chores that we do for ourselves and for others though, are done in love, as Marjorie Kelly suggests (Owning our Future). I’ll keep using the terms emotional economy, social commons and re-making as we go forward, and I hope the reader will keep in mind the broad reach that these terms encompass.

I hope that a parallel is now clear between how our economics regards nature and how it regards this re-making that we have been discussing. Wild nature is there all along, supporting everything we do, but often unacknowledged. Meanwhile, compassion and caring are there too, supporting the economies, but likewise going unacknowledged. Looking back at Figure 3.3, readers may have been somewhat puzzled, not to say, horrified, at the inclusion of the terms, ‘wild body’ and ‘wild mind’ in the diagram. The two economies, material and cultural, could well have been illustrated without this intrusion of hippydom and everything would have been fairly uncontroversial. Well, the reason is that these two neglected areas of society that we have been discussing, wild nature and compassion, are intimately linked. We could, if space had allowed, add further arrows to our diagram. What is the ultimate source of what is referred to as ‘labour’ in the material economy and ‘work’ in the cultural economy? It is wild body and wild mind. These in turn rely, for their sustenance, on both wild nature and the re-making of ourselves by way of compassion. Ultimately all of these things are ‘embodied’. Our modern societies have however, separated us from our wildness — stuffed us into classrooms, offices and factories and institutionalised our minds. Some have suggested that the cultural economy produces things beyond its imputs from nature — that to some extent, our abstract world of thoughts, ideas, imagination and creativity is independent of natural resources. The intention of such an idea is that we could have a sustainable economy without an ever-increasing reliance on limited physical resources. But no, this is not going to work. The abstract economy of culture, is just that, abstract, and cannot produce anything without its reliance on nature. We do the same with the financial economy — believing it can somehow, in and of itself, produce more wealth. It cannot. Someone, somewhere has to pay for the ‘wealth’ the financial economy claims to create, and that wealth again has its ultimate source in wild body and wild mind.

Once again, I’d like to make clear that I am not seeking to change economics, only to expand our view of where all its inputs are coming from, if you will, and to shed some light on matters that are currently downplayed or neglected. If we were to fully address matters in relation to wild nature, be fully responsible in terms of what we take from nature by way of natural resources, and fully cleaned up after ourselves, by way of recycling and stopping pollution, this would not change economics. It would be, perhaps, an additional cost to the economy. As Richard Swift points out (SOS, Alternatives to Capitalism) these additional costs ultimately get passed on to the consumer, and thus the poor will suffer more than the rich. But does this mean we should not seek the changes? It could be argued that everything and anything that leads to higher costs causes more problems to the poor than to the rich. But that is not a reason for not making the change. Instead, it would be a reason for balancing things out with a fairer distribution of wealth through taxation or by some other means. If the natural commons are not taken properly into account, then the devastation that will be caused in the longer term will be even more of a problem to the poor than doing something about the problems now. And then there will not be a way back — we cannot tax our way out of ecological collapse. We could also point out that the extra costs envisaged by Swift and others could be, at worst, only temporary problems. It might be that an economy that really took proper cognisance of wild nature would ultimately be more prosperous rather than less.

Value

One of the discussions about capitalism, that we will pick up on below, is to ask when normal trading turned into capitalism proper. One answer given to this question is related to value. The idea is that at one time — and even now, in some countries — goods were produced solely for the purpose of being useful, and often by the person who would be using them. So, they had ‘utility value’. There came a point however, when selling goods to others became more important than merely providing for one’s own basic needs, or the basic needs of one’s family or small community. This, in turn, is known as ‘exchange value’. Common sense tells us that we might well spend a great deal of time and effort fashioning some tool or weapon for our own use and, in a way, as our time is not dictated by a financial world, the degree of effort is not too important. Okay, so the tool-maker might have spent the time fishing, or hunting, or just sleeping, but no-one’s counting. In an industrial society however, the costs and time involved in producing goods for exchange become increasingly important. A business has to weigh up how much it pays for materials, labour, its buildings, energy costs and so on, and then determine whether it can still sell its product and make enough money to survive. Economists see, in particular, the cost of labour to be critically important in this analysis, so, in their terms, it is the labour expended on producing a product that creates its value. (It is ‘concrete labour’ that produces utility value — and abstract labour that produces ‘exchange value’. The names given by economists reinforce the idea that we are separated — abstracted — from our making by entering into an exchange economy.) This proposes a labour-based theory of value. For our purposes, in this chapter, this leads to two observations.

The first observation about the labour theory of value is that it is not so obvious that the value of a particular product is really just related to the wages of the labourer, from the buyer’s point of view. Natural assets, for instance, have a value even when there is very little work involved in gathering them. The value of money also affects the price of commodities, so also does the way those commodities are perceived by the buyer — for instance, jewellery, artworks etc, can have a price well above their content in labour, because of the way they are valorised by society. As noted above, the theory separates the worker from their product — we became alienated from our making. And from the buyer’s, or the consumer’s point of view, the product ceases to have anything of the labourer within it — the product has become mere commodity, and as such, holds only a ‘commodity value’ or, ‘extrinsic value’.

The second observation — and most important to our discussion — is that the true cost of labour is not really recognised in this analysis. The reason is that the wage given to the worker is, in theory, at least sufficient for the worker to ‘reproduce’ themselves, and therefore to return to work the following day and continue in the production process. (The ‘real’ price of labour is the commodities for which the labour can be exchanged. The ‘nominal’ price of labour is the monetary value of those commodities.) But this act of ‘reproduction’ (what I am referring to as ‘re-making’ in this book) is only seen in terms of how much it costs for someone to live a reasonable life in society. As we’ve explored above, it disregards the input of compassion, friendship, love, community, solidarity and all the other elements that go to make up the social commons. As we touched on earlier, the production process therefore takes these as a ‘positive externality’, in other words, it profits from what the wider community provides for it free of charge. (Pollution, by contrast, is known as a ‘negative externality’, something bad added to society, but for which, again, the economy does not pay.)

In contrast to the extrinsic value of commodities, there is ‘intrinsic value’. I have mentioned intrinsic value previously in relation to wild nature — saying that nature has a value just for itself. We can expand this idea here to include, firstly, ourselves, as part of wild nature. Then, from the discussion above, I hope the reader will see that there is intrinsic value to our ‘making’, to the things that we produce, either for our own use or to barter or sell to others. There is intrinsic value also in the ideas we have — our imagination and creativity — the cultural commons. And finally, there is intrinsic value in our social relations — what I have called our ‘re-making’ — the social commons. The material economy monetises the natural commons (or that part of it we use as resources). We are a little more hesitant about monetising the cultural economy — or, creativity and imagination — but we have noted the parallels between the cultural and the material economies earlier in the work. What about monetising the emotional economy? A little is already monetised — the ‘services’ side of the material economy, often termed ‘social care’. But the rest is free — or, a gift — it has intrinsic value. Perhaps care, emotion, affection, compassion and love just have a deeper level of abstraction and will always resist commodification and monetisation.

For economics, every value can be translated into a monetary value — everything is commodified. So some might think it is entirely appropriate for economics to disregard the ideas I have described above. But the danger then is that we disregard the very things that give us sustenance. Anything that stands outside the process of commodification tends to get ignored. Before we move on, we need to get a handle on how this commodification and monetisation works in practice.

Value and Money — The Financial Economy

Back in Chapter 2, it was with some reluctance that we noted there is a separate financial economy, and indeed that it is often referred to as ‘capital’. (Henry George reminds us: ‘nothing can be capital […] that is not wealth — that is to say, nothing can be capital that does not consist of actual, tangible things…’ George continues: ‘…the stocks, bonds, etc., which constitute another great part of what is commonly called capital, are not capital at all; but, in some of their shapes, these evidences of indebtedness so closely resemble capital and in some cases actually perform, or seem to perform, the functions of capital…’ (Henry George — Progress and Poverty. We should note however that Marx, and many recent economists, make a very close link between capital and money, so the question is not entirely settled.) The story at the head of this chapter is contrasting two economies — the financial and the emotional — and contrasting money, as currency, with compassion, as a form of ‘currency’ for the social commons. So, before we go on, we need to get more of an idea of how money functions in the economy.

Money wasn’t always the problem it is turning out to be. As we’ll hopefully see below, the financial economy is there to serve the material economy — to oil its wheels, so to speak — and allow for all the exchanges and operations needed for the smooth-running of society. Money, primarily, is a medium of exchange — it is a veil between us and the simple exchange of goods and services that it allows. As a medium of exchange, the value of money is itself arbitrary. Setting its value against something else, such as gold, is likewise arbitrary, because the value of that other thing is just a social construct — an agreement within society as to what constitutes stored value. If a society fails, then the value of money can plummet or become non-existent, as has happened from time to time throughout history.

Money is further premised on trust in the future. Trust in money means that it is a store of value. Trust in credit, for instance, amounts to believing that someone, somewhere — probably the person who has borrowed the money — will produce goods and services to earn money to pay back their loan. So money is a standard of deferred payment. This process need not involve ‘growth’ necessarily, or indeed the exploitation of non-renewable commons, but, of course, very often it does.

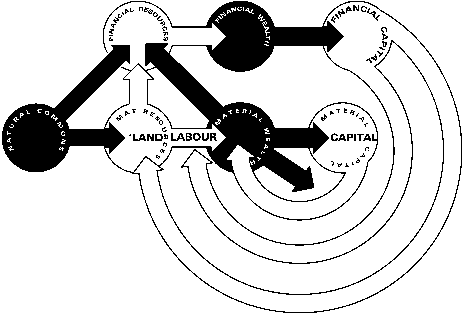

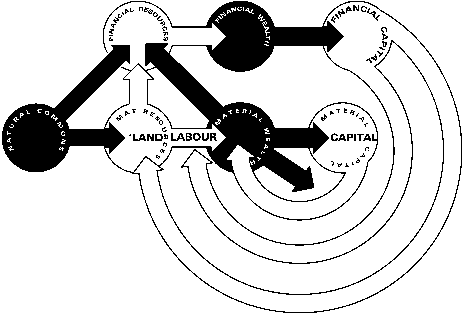

The figure below builds on the figures in Chapter 3, to show the financial economy.

Figure 7.1

The figure is really just showing that there is a flow of money around the material economy, keeping the process going, and in this sense, the use of money is a benign use. Changing our views, for instance, with regard to wild nature, would not alter the basic functioning of the economy and would not alter the flow of money to support it — the same structure would still pertain, but society’s increased care of wild nature would nonetheless greatly improve our lives.

With all of the above thoughts in mind, we can return now to some of those questions raised in the Introduction.

What Should we Own?

Whilst governments usually have policies in place to combat monopolies, the biggest monopoly of all is allowed to play out without much comment or criticism — it is, of course, the speculation in land and property. Chapter 2 on ownership looked, in particular, at land. The chapter suggested that ownership itself is less of an issue than the notion of being a steward or custodian of land, and thereby having a measure of responsibility with regard to how the land is used. Chapter 3, on the commons, expanded this thought to include all areas of commons — the oceans, the air, fish stocks, ores, minerals, forests, and so on. Chapter 3 suggested that since these resources could be considered as held in common by all of us, then anyone who taps into them should pay something back to the rest of the population.

In Chapter 4, on polity, we saw how the question of ownership is an important factor in the type of governance system we may choose to adopt. Some systems reject all forms of ownership and suggest everything in life is shared. Other systems, meanwhile, regard ownership as a primary right of the individual and see governments responsible for protecting that right — even if this means that distribution to the less fortunate members of society is thereby curtailed.

In this chapter, and from the perspective of the material economy, we’ve seen that if owners of land, and all businesses that extract resources from nature, are required to pay something back to the community for this privilege, then this does not change economics, it simply means that additional costs are added to the business as a result. What was once a positive externality is now a further cost that needs to be met. This might mean that the process, whatever it may be, becomes uneconomic, so the business will either have to find ways to reduce costs in other areas of its production, or it will have to change to producing something else that does not incur such heavy production costs.

So, nothing changes in economics, but a lot may change by recognition of a commons. Two points can then be raised. Firstly, if we were g