3. Defining the Commons

A few weeks into the Dundee Commons Group and an odd conversation takes place at one of the fortnightly meetings. We had the strange incident with the five-pound notes a few weeks previously. (As told in Chapter 2. Had everyone else sellotaped their notes together?) Now we learn there is a bit of money available to fund the year-long project. We’re all going to be putting in some effort to the project — so should we divvy up this money? There are about twenty of us at this stage, so it doesn’t work out to much. Why bother? — that’s my feeling, as the conversation is drifting on. Then my thoughts start to turn to what a commons should really be doing with money — and indeed stuff generally. I imagine us all getting into the hall next to the café where we are meeting. We have brought our belongings in suitcases, boxes and wheelbarrows. It is all deposited in a large heap on the floor. The lights are switched off. We all undress and add our clothes to the pile of stuff. Then it’s open season, to rummage through the loot and get kitted out with new clothes, books and whatever else takes our fancy. Now that would be a commons! But regrettably it never happened and I still have my own underwear.

A Commons Exists for us Now

Before we embark, I must issue a stodgy pudding warning at this juncture. This commons chapter is probably the most difficult to follow. I have tried to sweep up all the various authors’ thoughts on the meanings of capital and commons and harmonise them into something that I trust is coherent. I hope the reader will persevere through the following pages, so as to get a grounding for the remainder of the book. More palatable puddings follow in later chapters, and take up the ideas introduced here to build towards a new story. Many of the terms introduced in this chapter are also summarised in the Glossary, so it is worth checking back there for an overview, particularly with regard to the various ‘commons’ and ‘capitals’ we will be exploring.

A commons means different things to different people. In this work I am mostly taking it to have the political meaning of shared land and property and shared resources.

In much of the developing world a commons is still the norm rather than the odd aberration that it has come to be in developed nations. I’m suggesting though that for the developed world a commons still exists, but in less recognisable forms. For instance, we accept that most roads are publicly owned, there are public buildings, city squares and pavements. Arguably this is public space rather than commons, but it is still a ‘commonised’ resource. Up to a point, wealth is shared by taxation; in the UK we are not forced to pay directly for public services such as education and health care, so the costs of these facilities are commonised.

So, if we were to be more aware of the commons, we’d see that it does not have to be re-invented where there has previously been nothing remotely considered a commons. It is more a question of shifting the boundaries — literally and metaphorically — as to what is described as commons and what is not. In the light of these thoughts, this chapter asks: What should we share? Are there changes to the way a commons is defined in society that would make us all happier and also protect nature and maintain her and us in ecological stability?

The Tragedy of the Commons

Anyone who has heard the term commons at all is likely to immediately think of the so-called ‘Tragedy of the Commons’. In its modern form, the name comes from an essay by Garrett Hardin. Traditionally, a commons was land available for ordinary people to do such things as graze cattle, collect firewood, forage and plant crops. Over time however, pressure from wealthy landowners resulted in ‘enclosures’, whereby the commoners, starting in England, were increasingly shut out from the land that had previously provided for their sustenance. Hardin, in his essay, takes up the traditional view of the commons and asks us to imagine individuals with cattle that they wish to graze on a particular piece of common land. Each such person, in their own self-interest, would be motivated to increase the number of cattle they graze so as to maximise the benefit derived from the land in the short-term. However, if everyone acts this way, then the land will be over-grazed and everyone will lose out. Hence, the tragedy. Hardin was not simply referring us back to something that might have happened in the past. His essay was really suggesting that we are doing the same thing on a much grander scale in today’s world. Whilst, in the developed world at least, there is little or no common land remaining, nonetheless there are ‘commons’ of fossil fuels, forests, clean water, fish, minerals and ores. In the interests of short-term gain, we burn our way through these and risk our long-term tragedy. (Critics of the Tragedy of the Commons theory point out that societies with common land for grazing or crops never have individuals acting in their own self-interest — there is always a community. But this, whilst true, rather misses the point of Hardin’s argument. The developed world is essentially a world of private interests — a Privatopia — so the Tragedy of the Commons is a very real possibility, indeed an increasing reality.)

In a book, Filters Against Folly, Hardin goes on to explain a bit more about dealing with the potential tragedy identified in his commons essay.1 Here, he makes the crucial distinction between a managed and an unmanaged commons. Hardin asks, Who benefits? Who pays? He suggests three alternatives — privatise, commonise or socialise. To privatise is to accrue the benefits of what we are doing, and to take responsibility for any losses. (This would be something like a business, acting responsibly, cleaning up any pollution, recycling, avoiding contributing to climate change and not using up resources that cannot be replaced.) To commonise, in Hardin’s terms, is essentially the Tragedy of the Commons scenario. Individuals or businesses privatise profits — so keep them to themselves, and thereby benefit in the short-term — but commonise losses. So, everyone pays for clearing up pollution, adapting to climate change, etc. This is a ‘commons’ of sorts, but it is a blind commons that is forced on us because of the selfishness and irresponsibility of others. To socialise, by contrast, is a ‘managed commons’. The gains and losses are shared out in a conscious and purposeful way. The full quote from Hardin’s book is given in the endnote.

We can see echoes of the same mindset in Adam Smith’s notion that if everyone is working blindly towards their own self-interest this creates — by way of an ‘invisible hand’ — a better society. But this idea is also the very idea that leads to the Tragedy of the Commons.

The important thing to grasp here is that a managed commons offers us the best hope of avoiding disaster in the future and a managed commons relies on community and good governance. So, it’s not that there is no commons right now. It’s that there is a commons of the worst possible kind. All the profit is extracted by a few. All the mess and waste is a shared cost borne by everyone. In summary, we are privatising profits and commonising losses when we could be sharing profits and privatising loss. (Some might have preferred if Hardin had exchanged what he meant by socialise and commonise in his explanations, but hopefully his meaning is still clear. It is a managed commons that Hardin is promoting. In fact, later in life, Hardin reflected that it might have been better for him to have called his essay, ‘The Tragedy of the Unmanaged Commons’.2) We might add here, as is often said, that there is no commons without community; indeed no commons without a suitable economic model to regulate it. Authors Maria Mies and Veronika Benholdt-Thomsen (The Subsistence Perspective) say:

‘In our view, we cannot simply say, “no commons without community”, we must also say, “no commons without economy”, in the sense of oikonomia, ie. the production of human beings within the social and natural household. Hence, reinventing the commons is linked to the reinvention of the communal and the commons-based economy.’ This production of the person is reflected in Sylvia Federici’s observation: ‘If commoning has any meaning it must be the production of ourselves as a common subject.’ (Sylvia Federici — Re-enchanting the World — Feminism and the Politics of the Commons.)

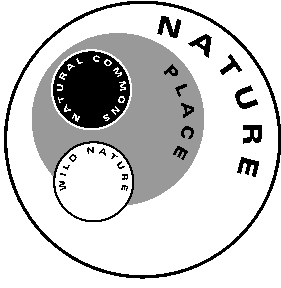

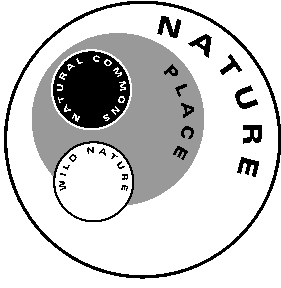

Natural Commons as Resource and Wild Nature

As we’ve seen above, the usual conception of the commons is about land that provides shared grazing for animals or shared space for growing food. And then we hear about ‘enclosures’, where the land becomes private property. Land is taken by those with power and then rented back to those who once used it for free. The idea of enclosure vividly describes the process whereby features of the world that were once wild and free have become commodified.

It is nature that provides the resources of the commons, and it is clearly nature still that provides the resources, even after enclosures have been devised by humans. We did not make a change to this by enclosing land, but we shifted attention from our reliance on nature over to an emphasis on production, rent and profit. The link back to nature became obscured — and this process has only become worse. I am using the term ‘natural commons’ for what nature provides for us — that is — the natural resources we need in order to survive. There are natural resources that can be replaced or replenished, whist other resources that, so far as the Earth is concerned, will be used up forever.

It should be pointed out though, that common land can be owned by someone, either an individual or the government, yet still remain a commons. As the last chapter tried to show, defining the commons is therefore not necessarily about ownership. The key thing is how the land is cared for and how a ‘managed commons’ is achieved.

The whole world has been at least indirectly affected by human activity. Chemicals in the air and water and changes to the atmosphere are all-pervasive and likely to increase in the foreseeable future. Even so, places that are as much untouched by humanity as possible are, I believe, critically important. The term I’m using in this work for such places is ‘wild nature’. Those places where, as yet, the human footprint is light, need to be preserved and protected at all costs. Wild nature belongs as much to the other fauna and flora with which we share this world as it belongs to us. Wild nature is where the privileges all belong to the animals, birds, insects, trees and plants that live there, instead of to us humans. If we go to such places at all, it is only to visit, or perhaps there are indigenous people living there, so close to nature that their footprint is exceptionally light. Wild nature, then, is not a ‘common wealth’ in the sense of offering us resources for food, energy, minerals or whatever. Its value is not even by way of absorbing Carbon Dioxide and regulating rainfall and its run-off and in preserving and making soil. Its real value is just for itself, and for its beauty and its nourishment to the human soul. Chapter 8 — Nature — considers these matters in more detail. American biologist E. O. Wilson has the idea of ‘half Earth’ — leaving (or, giving back) half the Earth to nature and using only the remaining half for humans. (At the time of writing, humans take up about two thirds of available land area — in the 1960’s it was only around one third.)

It might be argued that indigenous peoples, and even people who abandon ‘developed’ society and choose to live ‘off-grid’, are not necessarily going to draw the sharp distinction between ‘wild nature’ and ‘natural resources’ that I am suggesting here. It is a fair point, but for one thing, the numbers of such people are very small, so their impact is minimal. For another thing, the belief systems of indigenous people (and even some off-gridders) will often mean they live in a careful balance with nature. Even though that balance may not be as I have defined it here, I think something similar is implicit. Indigenous people often have a relationship and reciprocity with nature that ‘developed’ societies have largely lost and which would be difficult to replicate.

The relationship of nature, place, the natural commons and wild nature are shown in the figure below.

Figure 3.1 Nature, Place, Natural Commons, Wild Nature

The Commons, Wealth and Capital

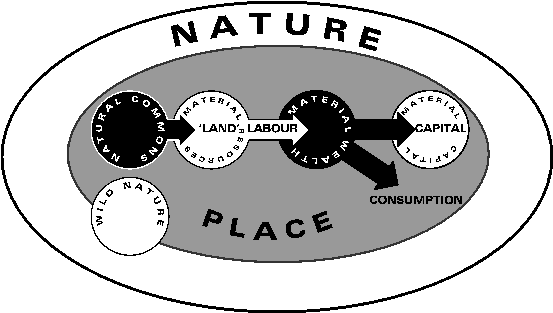

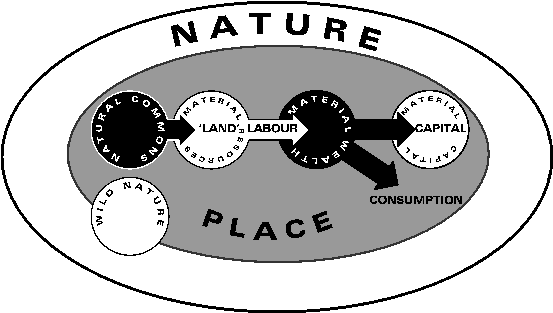

I have chosen to identify nature as partly a resource and partly as wild nature in order to clarify what is going on when we look to her for our sustenance. The resource aspect of nature — what I’m calling the natural commons — is what was traditionally just called ‘Land’ by economists, as we discussed in the previous chapter. I have separated this out from wild nature. Wild nature, as we’ve said above, belongs to the animals, the birds, the fish, the trees and the plants. We humans may find beauty and rest within wild nature, but not ‘resources’ in the traditional sense. Inevitably there is some cross-over. Old growth forests, for instance, sit on the borderline between what might be a resource and what might be preserved as wild nature. The important thing is to be conscious about what we are doing — to have a ‘managed commons’ of resources, in Hardin’s terms — rather than blindly and inadvertently destroying both wild nature and the natural commons. The first act of managing is to make clear this split between what is reasonable to be used and what needs to remain untouched.3

Classical economics recognises that for wealth to be wealth, some kind of work needs to be done in order to render natural resources useable. Some of this wealth is then consumed directly whilst some is retained as ‘capital’ for future use. We need to introduce human work and labour then in order to produce wealth and capital. All capital is wealth, but not all wealth is capital. This process was illustrated in Figure 2.1 in the last chapter. The figure below combines Figure 2.1 with Figure 3.1 to show how the two relate.

Figure 3.2 Natural Commons -> Resource + Work/Labour = Wealth ->

Capital + Consumption

An important point to note here — which I will discuss again below — is that our material economy with its capital, wealth and consumption, is not somehow ‘outside’ nature. Everything we do is within nature, even although many of the products of human endeavour — including our waste products and pollution — may seem ‘un-natural’. Environmentalists often balk at this conclusion, and perhaps the reason is that by calling everything ‘nature’ this might mean that those who exploit and/or destroy eco-systems then have an ‘excuse’ for their activities. But, in balance, I think describing everything as nature forces us to consider all of our activities as taking place within eco-systems, and this is a positive move.

Widening the Commons

As I’ve suggested earlier, the terms capital and commons have been expanded to include a variety of different things. Physical capital is sometimes used as an alternative term for the material resources nature provides. Human capital describes our ability to do work, essential, of course, for us to reproduce society through new goods and services. Cultural capital may be a term used to describe the contribution of intelligence, imagination and creativity. (It might be mentioned that imagination and creativity can be used for bad ends as well as good — so, presumably — ‘negative capital’. But in this work I am taking the terms to mean their more usual designation as something positive — something that builds rather than destroys.) Social capital is the value inherent in community that might be realised by way of voluntary work, informal help between neighbours and so on (sometimes referred to as ‘horizontal’ relations, in contrast to more formal work, which is termed ‘vertical’). Financial capital — dealt with more fully in Chapter 7 — recognises how integral money is to the flow of the economy, but also has a life of its own. Perhaps this proliferation of different capitals is a source of confusion. However, authors are perhaps attempting to show that the wealth of a culture owes as much to abstract qualities, such as compassion, imagination and social connections, as it does to physical resources. It might be that this suggests an attempt to quantify the less physical contributions and reduce them to number crunching. So the danger of the ‘capitals’ is that everything gets reduced to economics — or, elevated to economics — depending on your perspective. Along with this, it brings the notions of commodity, scarcity, transactional relationships and cost-benefit analyses. Maybe there is some justification for this with natural and cultural capital, but less so with social capital. But I think the intent of those authors who expand the meaning of capital is to show the richness of human culture and how the economy is actually built off a foundation of social connections. This is the more positive motivation that I have followed here.

To summarise the further definitions of capital:

Physical Capital — What I’ve called Natural Resources, or Material Wealth.

Human Capital — Value innate to people, including labour and work.

Cultural Capital — Intelligence, imagination and creativity

Social Capital — The value in the connections between people — as described by Robert Putman (Bowling Alone). See Chapter 7.

Financial Capital — Sometimes just used to refer to money, but better if it refers to the flow of money in the economy, as a support for the flow of physical resources, material wealth, consumption and material capital. See endnote4 and Chapter 7.

As with capital, there has also been a recent move to widen the meaning of commons, from the natural commons to the inclusion of human imagination and creativity. For the term natural commons itself — sometimes this is used to refer to all of nature. As discussed above however, I have suggested that we divide off part of nature as the commons part so as to recognise it is not all just a resource. But again, I don’t wish to quibble too much over definitions. The fact that many are describing nature in some way as a commons is to be greatly welcomed. The flexibility of all these terms — the commons and the capitals — is probably annoying to academics, but should remind us that all these things are fluid and waiting for us to resolve them into concrete decisions — indeed, our missions and aims will evolve over time, and the definitions we are discussing here will also evolve — it is always a process and not a destination.

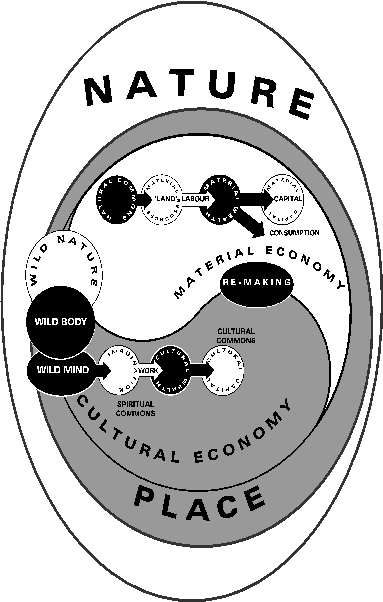

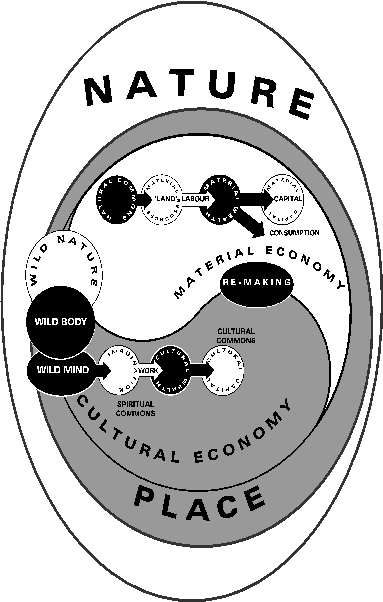

The definitions of the more abstract commons I am taking mostly from Charles Eisenstein (Sacred Economics). Eisenstein identifies a cultural commons of intelligence, inventiveness and technical know-how, a spiritual commons of imagination and creativity and a social commons of compassion and sharing. To summarise the definitions of commons:

Natural Commons — Sometimes referring to all of nature, but preferably referring to that part of nature that humans need for our sustenance, so is used as a material resource.

Cultural Commons — Eisenstein refers to intellectual property and creative copyright here, but I prefer to use the term to refer to the actual wealth produced, as in invention, art, music, literature and celebration, rather than the copyrighting of these. (Perhaps we should also include trademarks, patents and trade secrets, to be concise.)

Spiritual Commons — Imagination and creativity.

Social Commons — Compassion, gifts and sharing.5

Putting all this together:

Figure 3.3 The Material and Cultural Economies, showing the mirror progression from ‘Resource’ to ‘Capital’

The thing to note again, as with the previous figure, is how everything is held in nature — there is no ‘outside’. So, whilst we have considered splits in nature, these are just convenient ways for us to analyse the world and our activities within it. The other thing I’m trying to show in this figure is that there is a flow from ‘resources’ to ‘product’ in the more abstract world of culture, that mirrors the flow in the material world of manufacture and consumption. I hope this parallel is made clear by the diagram and by the two parallel flows. Where I have been able, in the figure above, I have shown how the various alternative definitions of capital and commons fit into these flows. The whole diagram is split into two types of economy — material and cultural.

I have added a few more ideas to the figure. For one thing, I’ve suggested that imagination and creativity are products of ‘wild mind’, which is itself a derivative of wild nature. I’ve also shown ‘wild body’ — balanced between the material and the cultural economies — and again a link between ourselves and wild nature. The reason for this, apart from my own affection for the terms — is to show how everything links back to nature. The cultural world is not as abstracted from our bodies and from the natural world, as is sometimes suggested. Nature underlies everything — we are all one ecology.

The reader will notice a few of the capitals and commons missing. These will be addressed in later chapters. For now, I have added one further bubble — Re-making, which appears to be floating alone outwith the flows of the two economies. This innocent word is essential for both economies to function — and its full implications are explored in Chapter 7.

Also, I want to briefly point out that those two main economies, the material and the cultural, are shown as linear processes. This is rather typical of our Western thought patterns, where things come from ‘nothing’ and are ultimately ‘consumed’ or destroyed. Everything else in the diagram seems to be floating around these linear processes. We could say that the way we try to organise all our economies is wanting to force us into these same linear arrangements that we ascribe to the material and the cultural. This sets up an awkward tension in the figure. There will be more to say on this in Chapter 7.

The parallels between the material economy and the cultural might suggest that culture is an ‘industry’ and its functioning mirrors very much the behaviour of the material economy. This might not be a problem for many — indeed it might be a welcome reflection, in their view, that there is a natural order in the way human culture functions, that operates across the broad range of human endeavour. However, for others, the commoning that we have spoken of with regard to natural resources above, takes on an even more important role when it comes to culture. As we’ve seen in the definitions from Eisenstein referenced above, there is a desire to group activities into new definitions of commons. These ideas can be grouped under the collective term, creative commons, and require some further exploration.

The Creative Commons

Just when you thought we’d mentioned every type of commons, along comes another! The term ‘creative commons’ has started to be used to refer to intellectual property and artistic copyright, so it may safely be regarded as a collective term for the cultural and spiritual commons, following the definitions above — hence, intelligence, creativity, imagination and technical know-how.

In the last chapter, we looked at ideas around the ownership of land and saw that one claim to ownership was on the basis of ‘improvement’. The idea was that if someone spent time and effort clearing a piece of ground of rocks and undergrowth, for instance, and then planted crops, the effort alone was sufficient for the person to claim ownership. (See John Locke.) In Classical economics, a similar argument is made to arrive at a general definition of wealth. Effort must be put in for wealth to be created. (Figure 2.1)

For imagination and creativity and their concomitant intellectual and creative copyright, we might take that same argument of improvement and apply it to the more abstract ideas of creativity and know-how. Minds need to be trained and the ideas of our imaginations take a lot of effort to bring to fruition as an invention, an artwork or a book. We might conclude therefore that the ‘improvement’ invested to bring something from an idea to an invention or a product mirrors the process of bringing natural resources into material wealth. The wealth that is created is cultural wealth and the capital derived from this is cultural capital.

Alternatively — and this is what is often behind the proposal for a creative commons — there is sometimes the wish that all cultural wealth should be a gift. Indeed, the term ‘creative commons’ tends to conflate imagination and creativity with their output — the cultural wealth — and downplays all the effort that goes into bringing the promptings of imagination to birth as actual inventions, artworks, music and so forth. It is an argument therefore against creative copyright and intellectual property rights. Personally, I have no quibble with those who wish to offer their gifts without remuneration. But I feel that the parallels of material wealth and capital with creative wealth and capital are worth making. The story at the head of the chapter was about that play-off between ‘gifting’ our creativity and deserving some kind of payment for the work rendered in bringing projects to fruition. I have to tell you that despite the trivial sums of money involved, it was quite a heated debate! A nerve had been touched. For artists engaged in social justice, this is a critical issue, so we can appreciate the challenge they have in resolving such questions. They may wish to see the cultural commons as emblematic of a ‘gift economy’, an idea we will be exploring in Chapter 7.

The creative commons sits on the border between the material economy (where most things are commodified) and the social commons (where most things are gifts). In fact, culture is a way that the importance of the social commons can be brought to light. There is a further way to look at things, which might be helpful. The reader may recall that in the previous chapter we considered the difference between ‘property’ and ‘possession’ with regard to land. The first term regarded land simply as commodity. The second recognised a social responsibility that went along with ownership; a responsibility that is expressed well by the notions of stewardship and custodianship. The debates over intellectual property rights and artistic copyright get very complex. The notion of stewardship may be a way that we can cut through these arguments to a sensible balance. As with land ownership, it is not ownership itself that is the real problem, it is how that ownership relates us to society. Social relations feature as much in the cultural economy as in the material — arguably more so. Could we find a way of rewarding the efforts of those who generate cultural wealth that also recognises the social aspect of what they produce? Could we have intellectual and artistic possession, rather than property — and what would this mean? The reader will appreciate, I’m sure, that a lot hinges on what we are like as people and how our societies function. I’m not going to explore this too much further here. However, I think one useful parallel can be drawn between the culture of today and how we treat the culture of the past.

Commons and Cultural Heritage

Some material production of past generations starts to be regarded as cultural wealth and of course artworks, literature and music endure beyond the lives of their creators. The cultural wealth feeds back to us as a resource, both in terms of artefacts and also physical places — buildings and landscapes. We often see these as a shared inheritance. This is partly because their creators are no longer around to benefit from what they have produced and also because communities, and sometimes nations, rightly regard such things as part of their culture. In the UK, we have protection for historic buildings by awarding them listed status, whilst whole areas of towns and cities may be protected in Conservation Areas. Landscapes, meanwhile, benefit from a variety of safeguards such as ‘Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty’, National Parks and ownership by the National Trust. Sometimes when historic buildings are under threat in other countries, concerns are raised, indeed there are places that have World Heritage Status to protect them. Likewise, artefacts in museums and art galleries can be the subject of national and international interest when they are bought and sold or moved to new locations.

Historic artefacts, buildings and landscapes can often still be owned by someone and the owners may derive benefit from their ownership. Such owners are not the creators of their property, but they may well be its protectors and custodians. We see items that were once the products of human creativity moving gradually into a kind of common ownership. The more significant those things are considered to be, the wider the pool of people who regard them as somehow a shared inheritance. In this process any current owners seem to have an ever greater degree of trust and responsibility placed upon them for what they ‘possess’.

I hope the parallel with intellectual property and artist copyright is clear. As with cultural heritage, our contemporary cultural wealth could be treated with similar kinds of mutual agreements and shared responsibilities. Indeed, we can refer this right back to our material economy, and recognise the shared responsibilities around the natural commons and wild nature.

The Prospects for Common Good Laws

According to Montesquieu: ‘the state owes all citizens a secure subsistence, food, suita