Motivation & the Birth of Gods

As an exercise of consciousness, imagine that you’re an all-knowing, all-powerful god. What would you do with that unlimited power? If you could do anything and everything you wanted and didn't have to answer to anybody or anything, what would you do? What would you change?

A common answer might involve a universe of happiness, where nobody could hurt anybody, and everyone could have anything they want, even if that’s just a few friends and a sunny field of grass. But what seems a simple question elicits some telling responses. One such response was “If I was God I would do exactly what he is doing now, which is seeing who has the faith to believe in me since I created you and act accordingly…”

Isn't it coincidental that gods are no smarter than the men that invented them? Throughout history, instead of just accepting reality, the inventors of gods unsuccessfully tried to reconcile a higher power and divine purpose and wisdom, with a cruel, unjust world ruled by selfishness. It's a bit of a mystery why creationists insist that the universe and life are by the design of an all-knowing god when anyone with a semblance of intelligence would create a world of happiness and pleasure as opposed to this world of pain and suffering. And those that don’t recognize the pain and suffering in this world are merely fools lost in their own selfish desire.

Why do people with the same universal needs vary so wildly in their temperment, and not recognize the same universal needs of others? To understand human behavior requires broader perspective; with a little more insight than the simple concept that all is planned and proceeding according to some mythical purpose. That’s not the reality of life. Life is driven by desire, not by design. Humanity is an amalgam of animated form and motivating idea. To understand any action; whether it be conscious behavior or otherwise, its cause must be determined. Every utterance and action has a motive; every effect has a cause. It’s the essence of motivating desire that determines how people feel, think and act. And it happens all too often that people invite adversity by accepting the results of actions without taking into consideration the true motives behind them.

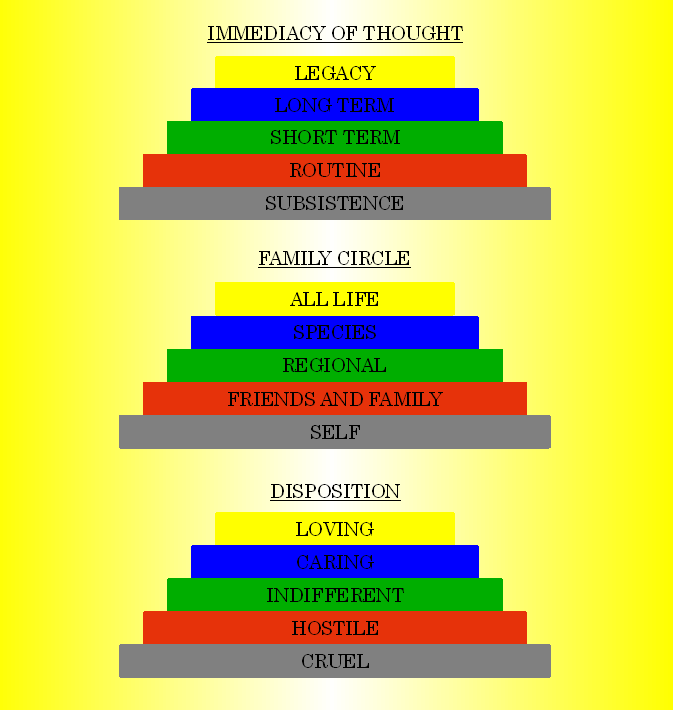

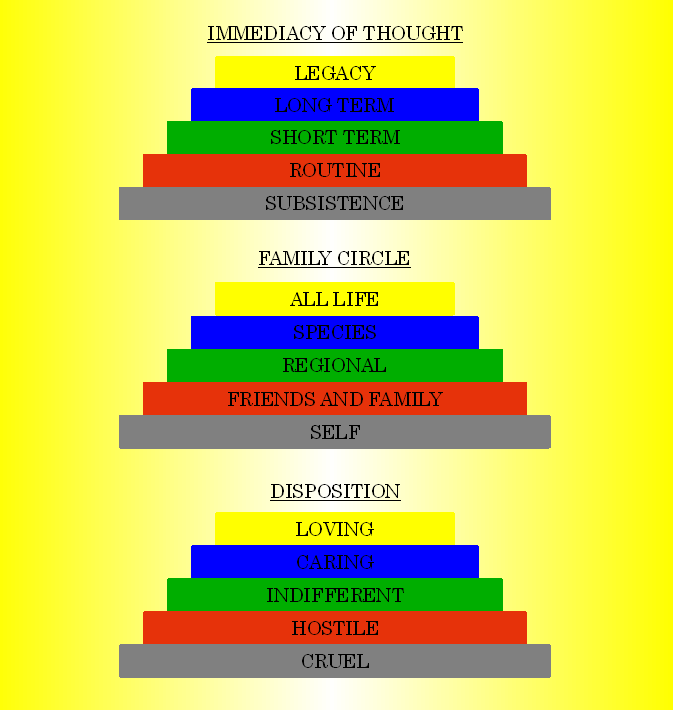

As far as motivation goes, there are many types, some of which correspond to differing levels of thought. Immediacy is the consideration of time and distance in the thought process. The most basic motivation is survival, as the dead neither need nor want. Immediate threats to health and safety receive top priority. Only after safety is secured can attention be practically turned to matters of physical desire and comfort, such as routine matters of housing and food acquisition. Beyond survival and physical needs people engage in short-term goals such as advancing their career and establishing a competitive advantage. Eventually, given the right opportunity, people set about long-term planning. Today that planning might be for retirement, saving for education, or perfecting a craft, but it might also include historical achievements, or contriving political or economic conquest. And a few thoughtful people at the top of the Immediacy Pyramid will choose their actions based on multi-generational, or legacy considerations they hope will have effects well beyond their own time and place.

Beyond classifying the timeliness of consideration, it’s also important to understand the distinction among subjects of concern. The term Family Circle can describe the breath of individuals whose well-being is favorably considered in one’s thought process. As with immediacy, there’s a wide range of concern people display for the health and happiness of others that defines the character of the individual. The most primitive of our kind care only about themselves; and of just slightly higher worth are those that care about friends and family. Above them are people that consider effects to broad groups such as a race, species or political subdivisions. Still others may care for some species, like horses and dogs, while not considering others, such as cows and pigs. And unfortunately it’s a rare person that cares about Health and Happiness for all the innocent earthlings. It’s that simple missing concern for others that accounts for the crime, violence and iniquity in civilization.

The third category of character distinction can be labeled Disposition. This category goes beyond time and subject to better describe one’s attitude toward others. In determining effect, family circle is crucial to establishing justness, and immediacy influences the scale of action. But the degree of depravity or magnanimity is often defined by the disposition of the actor. The worst character is so merciless and vile as to be labeled cruel. Less abusive savages are considered hostile, while indifferent people are neither friend nor foe. And better mannered people rise to the level of caring or even loving.

The very worth of people is determined by how well they rise above selfish desire, as reflected by their impact on others. Every purposeful evil of the world today; be it stealing or homicide, assault or simple insult; is the result of selfishness: the true root of all evil and deliberate iniquity; the desire to put one’s self before, seek leverage over, and take advantage of others. Selfishness plagues personal relationships, society, and all life on Earth. And it’s an inborn instinct as basic as any human emotion or behavior, though it must be overcome to achieve true personal growth and mutual benefit.

Not only perspective, but even justice is individual because the ability to experience pleasure or pain; the ability to feel emotion or contemplate reason; are products of advanced nervous system development. And due to the simple fact that nervous systems aren’t shared among individuals, people haven’t the ability to see, hear, feel and think the sights, sounds, sensations and thoughts of others.

By that limitation people and other animals are alone in their unique experiences; in their individual perceptions. Likewise, desires are similarly unique to individuals. But people can grow in goodness by seeking to understand and share the experiences and desires of others. Even though people may understand the benefits of cooperation and common generosity, they're handicapped by singular perspective and challenged to overcome it and grow beyond the self.

Perception is most certainly not, however, absolute in its restriction. People can see the pain of others, they can see the commonalities of all life, but selfishness has been compounded and furthered through the power of ignoble people spreading selfish ideas; some of which predate civilization because self-preservation and self-advancement was common to individuals well before any form of consideration.

Starting from nothing more than increasingly complex molecular interactions that provided a basis of ongoing animation and development, all of the knowledge and belief that people have ever gained, going back to reptilian ancestors and beyond, had to first be learned through observation, trial and error, and reason. The most primitive learning results from simple external stimuli. Examples of which are pain, fear and the watching others. It took a very, very long time, but eventually archaic people developed enough mental capacity to actually reason; instead of simply reacting to stimuli. In addition, different individuals had to learn the same things many times over before ever developing the communication skills necessary to effectively share knowledge and ideas.

Reasoning is synonymous with an internal motivation to learn, or figure things out. But, as an individual, early man’s perceptions were his own and so his interest was for himself. As an individual he could be oblivious to others. The first result of that singular perception that comes to mind is a lack of consideration and compassion for others. But there’s another important legacy of that self-absorption which still burdens society. To understand modern motivation it must be remembered that because he lived in an egocentric world early man didn’t just wonder why things happened; he wondered why things happened to him.

Coupled with his limited perception, early man had little experience, and very basic motivations. The quest for survival and fear of numerous serious health risks were still primary among his interests. He saw lightning but didn’t know why it might strike him. He saw fire but didn’t know why it might burn him. He saw rain and wondered why it might flood his home and why it might then abandon him for months at a time; whilst another man might see no rain at all and wonder why the river rose up against him without warning.

Whatever the phenomena, whether it be exploding mountains blasting smoke, ash and rocks into the sky or an angry Earth rumbling in displeasure as it opened and swallowed villages whole; when observation failed to answer his questions, early man was left to draw on his own experience, and project his personality into the subject of his curiosity. That practice of projection; of assigning one’s own values and opinions to things and events of mystery, has been instrumental in shaping history through man’s collective perception of reality. Because early man might strike at someone in anger, he believed an angry sky might strike at him with lightning. And because he related pain and hurtfulness with vengeance, he projected vengeful motive onto dangerous natural phenomena, that are, of course, totally void of consciousness.

In time, ancient man projected his personality into more than actions, but into objects as well. And his fanciful spirits grew more complex and powerful. Before he knew what was happening, he was imagining spirits everywhere he looked, though they could be neither seen nor heard. Supernatural agents ranged from spirits in objects that imbued special characteristics in matter, to ultimate realities pervading the entire universe; and from competing tribal gods to ultimate gods with neither beginning nor end and no limit to their power. In fanciful attempts to explain the unknown, man gave birth to gods and created that odd unreality to which they belong: religion.

And those simple, fragile gods; subject to the slight and whim of their creators and followers, whereby many were consigned to perpetual oblivion; slowly grew in importance. They began to take over the lives of men, growing stronger than men; stronger than any man; strong enough to command armies and consume nations. Those little spirits that flitted about the shadows of the unknown grew to become the powerful ideas that motivate and subjugate mankind.

But superstition born of ancient man can be recognized and neutralized by his descendants. Of man’s unreasonable, illogical creations, the sixteenth century philosopher Michel de Montaigne remarked, “Man is certainly stark mad; he cannot make a worm, and yet he will be making gods by the dozens.” And the 19th century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, observed that “All religions bear traces of the fact that they arose during the intellectual immaturity of the human race.”

And quite simply, religion was invented as a crutch for minds unable to come to grips with reality. Had people stopped at trying to explain what could be observed, and limited themselves to actual experience without resorting to fantasy, they would have been able to correct their own errors much sooner. But, their curiosity wasn’t limited to events they could see, it extended to matters of pure speculation. The death of loved ones grieved our ancestors, it set their hearts heavy and burned their minds with mourning. As people grew more inquisitive they contemplated the end of life; even coming to obsess over their own certain deaths.

Could anything be done to counter the inevitable finality of death? The question tore at people's emotions like wolves on a carcass; it haunted them like a grim reaper, stalking their every move, lurking in the shadows, just waiting for one unsuspecting moment of weakness. The loss of children, parents, friends, brothers and sisters was too much to bear. Death seemed so cruel and so unfair that people simply resorted to fantasy and ignored reality to alleviate their fear and frustration. Looking back at primitive man’s reaction to fear of the unknown, it’s easy to see why Thomas Edison declared “religion is all bunk, born of our desire to go on living.” The loss of everything people worked a lifetime to accomplish, and every memory and bond among friends, was so disheartening, so frightful, that simple man, in weakness, couldn’t resist grasping at any contrivance of eternal life. That’s why Karl Marx stated that religion was the opium of the people and Sigmund Freud compared it to a childhood neurosis.

The tragedy of entrenched ideology was set in motion early on. Children were hostage to the perspectives and beliefs of their parents. Premature conviction, the acceptance of doctrine that could not be observed, prevented people from continuing to search for the truth. Worse yet, people began to make decisions justified by their own pathetic myths.

By convincing themselves of their own truth, ancient people set life on Earth on an even more difficult path where error would be compounded by zeal. When people became entrenched in their beliefs they sought to impose them on others. And as truth was lost, it was hatred passed down through generations; with erroneous, even evil practices being demanded, disseminated and defended by all available means. Ancient zealots left future generations with archaic rules, invocations to errant and rampant violence, a warped sense of justice, and unfounded arrogance.

Before ancient people left written records, they’d compounded their errors many times over. Not content to just invent gods, people were concocting intricate relationships in the spirit world and elaborate rituals to appease their evermore peculiar gods; the gods that didn’t seem to be responding to their pleas. How can it be that any thinking being might cry out in a vacuum and imagine an answer from nothing? What’s worse, their fantasies of gods and demons fighting over mankind were the subject of the bulk of early writing. In the history of the world there’s never been a fraud like religion. Is it any wonder at all that people would be easy targets of hucksters, charlatans, and frauds; when they so enthusiastically embrace an empty promise of eternal glory? If a man wants something enough, can he not be convinced he shall have it?

Devilish absurdities were set in stone by devout followers that took what they were told to heart like they had seen it for themselves and then passed it to others with similar earnestness. The 19th century American speaker Robert G. Ingersoll characterized the passing of ideas between generations. He said, “For the most part we inherit our opinions. We are the heirs of habits and mental customs. Our beliefs, like the fashion of our garments, depend on where we were born. We are molded and fashioned by our surroundings.” Unfortunately, people fiercely resist learning what they think they already know, and in efforts to maintain their own position and perspective they have campaigned violently to prevent others from seeking the truth.

Ideas of gods and supernatural phenomena became more powerful than the simple minds they controlled. Priests were appointed to specialize in supplicating the gods. Those priests became early examples of “experts” with a biased interest in propagating their own position. Priests’ livelihoods, even their lives in many instances, were dependent on the religious conviction of the kings they served. Should the rulers of the land lose faith in the effectiveness of priests, then the priests were of little use and might as well themselves be sacrificed.

Unbeknownst to the common follower, seeking his own salvation, religious leaders had deeply vested mortal interest in multiplying the complexity and mystery of their craft. The more demanding and elusive the gods became, the more the services of the priests were needed. And by shaping gods into jealous, vengeful monsters, the priests gained a defense against expectations. They could then absolve themselves of failure by casting blame on the rulers and citizens for not satisfying the excessive requirements of fickle gods.

As people consumed with controlling matters they couldn’t even influence, religious leaders were captives of the gods of imagination, they were absorbed by the desperate culture, and hadn’t the wherewithal to distance themselves from their own fantasy. It was those experts and fervent devotees that couldn’t see the light for the shadows, the forest for the trees, the truth for the castle in the sky. And it has been to those mental toddlers that the masses have looked to for guidance.

In their selfish desires they resorted to murdering their fellow earthlings in ridiculous exercises of futility designed to buy the favor of their imaginary lords. And people were so disturbed and delusional that fathers sacrificed their own children. Those were not rational people possessing refined character, capable of high thought, and privy to divine inspiration. They were savages that couldn’t rise above superstition to free themselves of destructive dogma. Is it not concerning that humanity could be so base to believe in such nonsense? And is it not more concerning to realize the great tenacity with which people cling to their fortitude of ignorance?