D-7

Appendix D

Figure D-2. Dynamics of instability

D-37. Grievances are factors that can foster instability. They are based on a groups’ perception that other groups or institutions are threatening its interests. Examples include ethnic or religious tensions, political repression, population pressures, and competition over natural resources. Greed can also foster instability.

Some groups and individuals gain power and wealth from instability. Drug lords and insurgents fall in this category.

D-38. Key actors’ motivations and means are ways key actors transform grievances into widespread instability. Although there can be many grievances, they do not foster instability unless key actors with both the motivation and the means to translate these grievances into widespread instability emerge.

Transforming grievances into widespread violence requires a dedicated leadership, organizational capacity, money, and weapons. If a group lacks these resources, it will not be able to foster widespread instability.

Means and motivations are the critical variables that determine whether grievances become causes of instability.

D-39. Windows of vulnerability are situations that can trigger widespread instability. Even when grievances and means are present, widespread instability is unlikely unless a window of vulnerability exists that links grievances to means and motivations. Potential windows of vulnerability include an invasion, highly contested elections, natural disasters, the death of a key leader, and economic shocks.

D-40. Even if grievances, means, and vulnerabilities exist, instability is not inevitable. For each of these factors, there are parallel mitigating forces:

Resiliencies.

Key actors’ motivations and means.

Windows of opportunity.

D-41. Resiliencies are the processes, relationships, and institutions that can reduce the effects of grievances. Examples include community organizations, and accessible, legitimate judicial structures. Key actors’ motivations and means are ways key actors leverage resiliencies to counter instability. Just as certain key actors have the motivation and means to create instability, other actors have the motivation and the means to rally people around nonviolent procedures to address grievances. An example could be a local imam advocating peaceful coexistence among opposing tribes. Windows of opportunity are situations or events that can strengthen resiliencies. For example, the tsunami that devastated the instable Indonesian D-8

FM 3-07

6 October 2008

Interagency Conflict Assessment Overview

province of Aceh provided an opportunity for rebels and government forces to work together peacefully.

This led to a peace agreement and increased stability.

D-42. While understanding these factors is crucial to understanding stability, they do not exist in a vacuum.

Therefore, their presence or absence must be understood within the context of a given environment.

Context refers to longstanding conditions that do not change easily or quickly. Examples include geography, demography, natural resources, history, as well as regional and international factors.

Contextual factors do not necessarily cause instability, but they can contribute to the grievances or provide the means that foster instability. For example, although poverty alone does not foster conflict, poverty linked to illegitimate government institutions, a growing gap between rich and poor, and access to a global arms market can combine to foster instability. Instability occurs when the causes of instability overwhelm societal or governmental ability to mitigate it.

Assessment

D-43. Assessment is necessary for targeted engagement. Since most stability operations occur in less developed countries, there will always be a long list of needs and wants, such as schools, roads, and health care, within an operational area. Given a chronic shortage of USG personnel and resources, effective stability operations require an ability to identify and prioritize local sources of instability and stability.

They also require the prioritization of interventions based on their importance in diminishing those sources of instability or building on sources of stability. For example, if village elders want more water, but water is not fostering instability (because fighting between farmers and pastoralists over land is the cause), then digging a well will not stabilize the area. In some cases, wells have been dug based on the assumption that stability will result from fulfilling a local want. However, ensuring both farmers and pastoralists have access to water will help stabilize the area only if they were fighting over water. Understanding the causal relationship between needs, wants, and stability is crucial. In some cases, they are directly related; in others, they are not. Used correctly, the TCAPF, triangulated with data obtained from other sources, will help establish whether there is a causal relationship.

D-44. Understanding the difference between symptoms and causes is another key aspect of stability. Too often, interventions target the symptoms of instability rather than identifying and targeting the underlying causes. While there is always a strong temptation to achieve quick results, this often equates to satisfying a superficial request that does not reduce the underlying causes of instability and, in some cases, actually increases instability.

D-45. For example, an assessment identified a need to reopen a local school in Afghanistan. The prevailing logic held that addressing this need would increase support for the government while decreasing support for antigovernment forces. When international forces reopened the school, however, antigovernment forces coerced the school administrator to leave under threat of death, forcing the school to close. A subsequent investigation revealed that the local populace harbored antigovernment sentiments because host-nation police tasked with providing security for the school established a checkpoint nearby and demanded bribes for passage into the village. The local populace perceived the school, which drew the attention of corrupt host-nation police, as the source of their troubles. Rather than improve government support by reopening the school, the act instead caused resentment since it exposed the local populace to abuse from the police.

This in turn resulted in increased support for antigovernment forces, which were perceived as protecting the interests of the local populace. While the assessment identified a need to reopen the school, the act did not address a cause of instability. At best, it addressed a possible symptom of instability and served only to bring the true cause of instability closer to the affected population.

The Population

D-46. The population is the best source for identifying the causes of instability. Since stability operations focus on the local populace, it is imperative to identify and prioritize what the population perceives as the causes of instability. To identify the causes of instability, the TCAPF uses the local populace to identify and prioritize the problems in the area. This is accomplished by asking four simple, standardized questions.

(See paragraph D-49.)

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

D-9

Appendix D

Measures of Effectiveness

D-47. A measure of effectiveness is the only true gauge of success. Too often, the terms “output” and

“effect” are used interchangeably among civilian agencies. However, they measure very different aspects of task performance. While “outputs” indicate task performance, “effects” measure the effectiveness of activities against a predetermined objective. Measures of effectiveness are crucial for determining the success or failure of stability tasks. (See chapter 4 for a detailed discussion of the relationship between among assessment, measures of performance, and measures of effectiveness.)

THE TACTICAL CONFLICT ASSESSMENT AND PLANNING FRAMEWORK PROCESS

D-48. The TCAPF consistently maintains focus on the local populace. Organizations using the TCAPF

follow a continuous cycle of see-understand-act-measure. The TCAPF includes four distinct, but interrelated activities:

Collection.

Analysis.

Design.

Evaluation.

Collection

D-49. Collecting information on the causes of instability within an operational area is a two-step process.

The first step uses the following four questions to draw critical information from the local populace: Has the population of the village changed in the last twelve months?

What are the greatest problems facing the village?

Who is trusted to resolve problems?

What should be done first to help the village?

D-50. Has the population of the village changed in the last twelve months? Understanding population movement is crucial to understanding the operational environment. Population movement often provides a good indicator of changes in relative stability. People usually move when deprived of security or social well-being. The sudden arrival of dislocated civilians can produce a destabilizing effect if the operational area lacks sufficient capacity to absorb them or if there is local opposition to their presence.

D-51. What are the greatest problems facing the village? Providing the local populace with a means to express problems helps to prioritize and focus activities appropriately. The local populace is able to identify their own problem areas, thus avoiding mistaken assumptions by the intervening forces. This procedure does not solicit needs and wants, but empowers the people to take ownership of the overall process.

D-52. Who is trusted to resolve problems? Identifying the individuals or institutions most trusted to resolve local issues is critical to understanding perceptions and loyalties. Responses may include the host-nation government, a local warlord, international forces, a religious leader, or other authority figure. This question also provides an indication of the level of support for the host-nation government, a key component of stability. This often serves as a measure of effectiveness for stability tasks. It also identifies key informants who may assist with vetting or help to develop messages to support information engagement activities.

D-53. What should be done first to help the village? Encouraging the local populace to prioritize their problems helps to affirm ownership. Their responses form the basis for local projects and programs.

D-54. A central facet of the collection effort is determining the relationship between the symptoms and cause of the basic problem; understanding why a symptom exists is essential to addressing the cause. For example, an assessment completed in Afghanistan identified a lack of security as the main problem within a specific operational area. Analysis indicated this was due a shortage of host-nation security forces in the local area and an additional detachment of local police was assigned to the area. However, the assessment failed to identify the relationship between the symptom and cause of the problem. Thus, the implemented solution addressed the symptom, while the actual cause remained unaddressed. A subsequent assessment D-10

FM 3-07

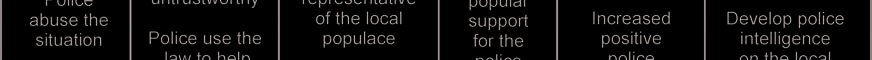

6 October 2008

Interagency Conflict Assessment Overview

revealed that the local police were actually the cause of the insecurity: it was common practice for them to demand bribes from the local populace while discriminating against members of rival clans in the area. By addressing the symptom of the problem rather than the cause, the implemented solution actually exacerbated the problem instead of resolving it.

D-55. The second step of collection involves conducting targeted interviews with key local stakeholders, such traditional leaders, government officials, business leaders, and prominent citizens. These interviews serve two purposes. First, targeted interviews act as a control mechanism in the collection effort. If the answers provided by key stakeholders match the responses from the local populace, it is likely the individual understands the causes of instability and may be relied upon to support the assessment effort. However, if the answers do not match those of the local populace, that individual may be either an uninformed stakeholder or possibly part of the problem. Second, targeted interviews provide more detail on the causes of instability while helping determine how best to address those causes and measure progress toward that end.

D-56. Information obtained during collection is assembled in a formatted TCAPF spreadsheet. This allows the information to be easily grouped and quantified to identify and prioritize the most important concerns of the population.

Analysis

D-57. During analysis, the information gained through collection is compiled in a graphical display. (See figure D-3.) This display helps identify the main concerns of the population and serves a reference point for targeted questioning. The TCAPF data is combined with input from other staff sections and other sources of information—such as intergovernmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and private sector entities. All this input is used to create a prioritized list of the causes of instability and sources of resiliency that guide the conduct of stability operations.

Figure D-3. Analyzing causes of instability

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

D-11

Appendix D

Design

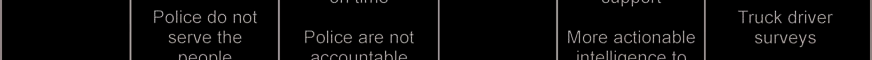

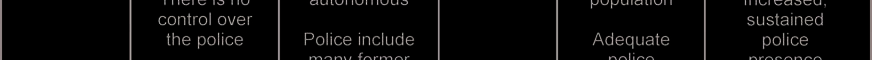

D-58. The design effort is informed through analysis, the results of which are used to create a tactical stability matrix for each of the causes of instability. (See table D-1.) After identifying the causes of instability and sources of resiliency, a program of activities is designed to address them. Three key factors guide program design, which ensures program activities:

Increase support for the host-nation government.

Decrease support for antigovernment forces.

Build host-nation capacity across each of the stability sectors.

Table D-1. Tactical stability matrix

D-59. The tactical stability matrix and program activities form the basis for planning within an operational area. The plan targets the least stable areas and ensures instability is contained. It is nested within the higher headquarters plan and details how specific stability tasks will be integrated and synchronized at the tactical level. The TCAPF data is collated at each echelon to develop or validate assessments performed by subordinate elements.

Evaluation

D-60. The TCAPF provides a comprehensive means of evaluating success in addressing the sources of instability. Through measures of effectiveness, analysts gauge progress toward improving stability while diminishing the sources of instability. Measures of effectiveness are vital to evaluating the success of program activities in changing the state of the operational environment envisioned during the design effort.

D-61. While evaluation is critical to measuring the effectiveness of activities in fostering stability, it also helps to ensure the views of the population are tracked, compared, measured, and displayed over time. Since these results are objective, they cannot be altered by interviewer or analyst bias. This creates a continuous narrative that significantly increases situational awareness.

Best Practices and Lessons Learned

D-62. Capturing and implementing best practices and lessons learned is fundamental to adaptive organizations. This behavior is essential in stability operations, where the ability to learn and adapt is often the difference between success and failure. The TCAPF leverages this ability to overcome the dynamics of the human dimension, where uncertainty, chance, and friction are the norm. Examples of best practices and lessons learned gained through recent experience include the following:

D-12

FM 3-07

6 October 2008

Interagency Conflict Assessment Overview

Activities and projects are products that foster a process to change behavior or perceptions.

Indicators and measures of effectiveness identify whether change has occurred or is occurring.

Perceptions of the local populace provide the best means to gauge the impact of program

activities.

Indicators provide insight into measures of effectiveness by revealing whether positive progress is being achieved by program activities. (See paragraph 4-69 for a discussion on the role of indicators in assessment.)

“Good deeds” cannot substitute for effectively targeted program activities; the best information engagement effort is successful programming that meets the needs of the local populace.

Intervention activities should—

Respond to priority issues of the local populace.

Focus effort on critical crosscutting activities.

Establish anticorruption measures early in the stability operation.

Identify and support key actors early to set the conditions for subsequent collaboration.

Intervention activities should not—

Mistake “good deeds” for effective action.

Initiate projects not designed as program activities.

Attempt to impose “Western” standards.

Focus on quantity over quality.

SUMMARY

D-63. The TCAPF has been successfully implemented in practice to identify, prioritize, and target the causes of instability in a measurable and immediately accessible manner. Since it maximizes the use of assets in the field and gauges the effectiveness of activities in time and space, it is an important tool for conducting successful stability operations.

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

D-13

This page intentionally left blank.

Appendix E

Humanitarian Response Principles

BACKGROUND

E-1. Even in those situations where military forces are not directly involved, a focused and integrated humanitarian response is essential to reestablishing a stable environment that fosters a lasting peace to support broader national and international interests. Providing humanitarian aid and assistance is primarily the responsibility of specialized civilian, national, international, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations and agencies. Nevertheless, military forces are often called upon to support humanitarian response activities either as part of a broader campaign, such as Operation Iraqi Freedom, or a specific humanitarian assistance or disaster relief operation. These activities consist of stability tasks and generally fall under the primary stability task, restore essential services. This appendix outlines the guiding principles used by the international community to frame humanitarian response activities.

E-2. Generally, the host nation or affected country coordinates humanitarian response. However, if the host nation or affected country is unable to do so, the United Nations often leads the international community response on its behalf. The principles that guide the military contribution to that response are fundamental to success in full spectrum operations. These principles reflect the collective experience of a diverse group of actors in a wide range of interventions conducted over decades across the world. They help to shape the humanitarian component of stability operations.

E-3. United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/182 governs the humanitarian response efforts of the international community. It articulates the principal tenets for providing humanitarian assistance—

humanity, neutrality, and impartiality—while promulgating the guiding principles that frame all humanitarian response activities. These guiding principles are drawn from four primary, albeit separate, sources:

InterAction and the Department of Defense.

International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

Oslo Guidelines.

Interagency Standing Committee.

INTERACTION AND THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

E-4. InterAction is the largest coalition of U.S.-based nongovernmental organizations focused on the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people. Collectively, its members work in every developing country.

Members meet people halfway in expanding opportunities and support gender equality in education, health care, agriculture, small business, and other areas.

RECOMMENDED GUIDELINES

E-5. The following guidelines facilitate interaction between American forces and nongovernmental humanitarian agencies (NGHAs). This latter group engages in humanitarian relief efforts in hostile or potentially hostile environments. Simply, these guidelines recognize that military forces and NGHAs often occupy the same space, compete for the same resources, and will likely do so again. When they share an operational area, both should strive to follow these guidelines; they recognize that extreme circumstances or operational necessity may require deviation. When aid organizations deviate from established guidelines, they must make every effort to explain their reasoning.

E-6. Military forces use the following guidelines consistent with protection, mission accomplishment, and operational requirements:

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

E-1

Appendix E

When conducting relief activities, military personnel wear uniforms or other distinctive clothing to avoid being mistaken for NGHA representatives. These personnel do not display NGHA

logos on any clothing, vehicles, or equipment. This does not preclude the appropriate use of symbols recognized under the law of war, such as a red cross. U.S. forces may use the red cross on military clothing, vehicles, and equipment when appropriate.

Military personnel visits to NGHA sites are by prior arrangement.

NGHA views on the bearing of arms within NGHA sites are respected.

NGHAs have the option of meeting with military personnel outside military installations for information exchanges.

Military forces do not describe NGHAs as “force multipliers” or “partners” of the military, or in any fashion that could compromise their independence or their goal to be perceived by the

population as independent.

Military personnel and units avoid interfering with NGHA relief efforts directed toward

segments of the civilian population that the military may regard as unfriendly.

Military personnel and units respect the desire of NGHAs not to serve as implementing partners for the military in conducting relief activities. However, individual nongovernmental

organizations may seek to cooperate with the military. In this case, such arrangements will be carried out while avoiding compromise of the security, safety, and independence of the NGHA community at large, NGHA representatives, or public perceptions of their independence.

E-7. NGHAs should observe the following guidelines:

NGHA personnel do not wear military-style clothing. NGHA personnel can wear protective

gear, such as helmets and protective vests, provided that such items are distinguishable in color or appearance from military-issue items.

Only NGHA liaison personnel—and not other NGHA staff—may travel in military vehicles.

NGHAs do not co-locate facilities with facilities inhabited by military personnel.

NGHAs use their own logos on clothing, vehicles, and buildings when security conditions

permit.

Except for liaison arrangements, NGHAs limit activities at military bases and with military personnel that might compromise their independence.

NGHAs may, as a last resort, request military protection for convoys delivering humanitarian assistance, take advantage of essential logistic support available only from the military, or accept evacuation assistance for medical treatment or for evacuating a hostile environment. Providing such military support to NGHAs is not obligatory but rests solely within the discretion of the military forces. Often it will be provided on a reimbursable basis in accordance with applicable U.S. law.