Any civil-military coordination must avoid jeopardizing the longstanding local network and trust that humanitarian agencies created and maintained.

NEEDS-BASED ASSISTANCE FREE OF DISCRIMINATION

E-45. Humanitarian assistance is provided based on needs of those affected, taking into account the local capacity already in place to meet those needs. The independent assessment and humanitarian assistance are given without adverse discrimination of any kind. Assistance is given regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, social status, nationality, or political affiliation of the recipients. All populations in need receive aid equitably.

CIVILIAN-MILITARY DISTINCTION IN HUMANITARIAN ACTION

E-46. At all times, agents of aid clearly distinguish between combatants and noncombatants. They identify those actively engaged in hostilities as well as civilians and others who do not or no longer directly participate in the armed conflict. The latter group may include the sick, wounded, prisoners of war, and demobilized ex-combatants. The law of armed conflict protects noncombatants by providing immunity from attack. Thus, humanitarian workers must never present themselves or their work as part of a military operation, and military personnel must refrain from presenting themselves as civilian humanitarian workers.

OPERATIONAL INDEPENDENCE OF HUMANITARIAN ACTION

E-47. In any civil-military coordination, humanitarian actors take the lead role in undertaking and directing humanitarian activities. The agents preserve independence of humanitarian action and decisionmaking both at the operational and policy levels. Humanitarian organizations do not implement tasks on behalf of the military nor represent or implement their policies. Basic requisites must not be impeded. These requisites can include freedom of movement for humanitarian staff, freedom to complete independent assessments, freedom to select staff, freedom to identify beneficiaries of assistance based on their needs, or free flow of communications between humanitarian agencies as well as with the media.

SECURITY OF HUMANITARIAN PERSONNEL

E-48. Any perception that humanitarian actors are affiliated with the military could impact negatively on the security of humanitarian staff and their ability to access vulnerable populations. However, relief workers must identify the most expeditious, effective, and secure approach to ensure the delivery of vital assistance to vulnerable target populations. They balance this approach against the primary concern for ensuring staff safety. The decision to seek military-based security for humanitarian workers should be viewed as a last resort option when other staff security mechanisms are unavailable, inadequate, or inappropriate.

DO NO HARM

E-49. Considerations on civil-military coordination must be guided by a commitment to “do no harm.”

Humanitarian agencies must ensure at the policy and operational levels that any potential civil-military 6 October 2008

FM 3-07

E-9

Appendix E

coordination will not contribute to further the conflict nor harm or endanger the beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance.

RESPECT FOR INTERNATIONAL LEGAL INSTRUMENTS

E-50. Both relief workers and military forces must respect laws pertaining to human rights as well as other international norms and regulations, including instruments for human rights.

RESPECT FOR CULTURE AND CUSTOM

E-51. Agents of aid maintain respect and sensitivities for the culture, structures, and customs of the communities and countries. Where possible and to the extent feasible, they find ways to involve the intended beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance and local personnel in the design, management, and implementation of assistance, including in civil-military coordination.

CONSENT OF PARTIES TO THE CONFLICT

E-52. The risk of compromising humanitarian operations by cooperating with the military might be reduced if all parties to the conflict recognize, agree, or acknowledge in advance that humanitarian activities might necessitate civil-military coordination in certain exceptional circumstances. Negotiating such acceptance entails contacts with all levels in the chain of command.

OPTION OF LAST RESORT

E-53. Use of military assets, armed escorts, joint humanitarian-military operations, and any other actions involving visible interaction with the military must be the option of last resort. Such actions may occur only when no comparable civilian alternative exists and only the use of military support can meet a critical humanitarian need.

AVOID RELIANCE ON THE MILITARY

E-54. Humanitarian agencies must avoid depending on resources or support provided solely by the military. Any resources or support provided by the military should be, at its onset, clearly limited in time and scale. Often resources provided by the military are transitory in nature. When higher priority military missions emerge, such support may be recalled at short notice and without any substitute support.

E-10

FM 3-07

6 October 2008

Appendix F

Provincial Reconstruction Teams

For the post-September 11 period, the chief issue for global politics will not be how to cut back on stateness but how to build it up. For individual societies and for the global community, the withering away of the state is not a prelude to utopia but to disaster. A critical issue facing poor countries…is their inadequate level of institutional

development. They do not need extensive states, but they do need strong and effective

ones within the limited scope of necessary state functions.

Francis Fukuyama

State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century 3

PRINCIPLES OF PROVINCIAL RECONSTRUCTION TEAMS

F-1. A provincial reconstruction team (PRT) is an interim civil-military organization designed to operate in an area with unstable or limited security. The PRT leverages all the instruments of national power—

diplomatic, informational, military, and economic—to improve stability. However, the efforts of the PRT

alone will not stabilize an area; the combined military and civil efforts are required to reduce conflict while developing the local institutions to take the lead in national governance, the provision of basic services, fostering economic development, and enforcement of rule of law.

F-2. The development community uses specific principles for reconstruction and development. (See appendix C.) These enduring principles represent years of practical application and understanding of the cultural and socioeconomic elements of developing nations. Understanding these principles enables development officials to incorporate techniques and procedures effectively to improve economic and social conditions for the local populace. By applying the principles of reconstruction and development, the development community significantly improves the probability of success. Timely emphasis on the principles increases the opportunity for success and provides the flexibility to adapt to the changing conditions. This community assumes risk in projects and programs by failing to adhere to the principles.

F-3. A PRT does not conduct military operations or directly assist host-nation military forces. The PRT

helps the central ministries distribute funds to respective provincial representatives for implementing projects. This assistance encompasses more than a distribution of funds; it includes mentoring, management, and accountability.

F-4. PRTs aim to develop the infrastructure necessary for the local populace to succeed in a post-conflict environment. A PRT is an integral part of the long-term strategy to transition the functions of security, governance, and economics to the host-nation. This team serves as a combat multiplier for commanders engaged in governance and economic activity, as well as other lines of effort. The PRT also serves as a force multiplier for United States Government development agencies engaged across the stability sectors.

A PRT assists local communities with reconciliation while strengthening the host-nation government and speeding the transition to self-reliance. To accomplish this mission, the PRT concentrates on three essential functions: governance, security, and reconstruction.

GOVERNANCE

F-5. Within an operational area, a PRT focuses on improving the provincial government’s ability to provide effective governance and essential services. Strengthening the provincial government is important given the decentralization of authority common to a post-conflict environment. For example, under

3 © 2004 by Francis Fukuyama. Reproduced with permission of Cornell University Press.

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

F-1

Appendix F

Saddam Hussein’s regime In Iraq, provincial officials received detailed directions from Baghdad. Under the current structure, provincial officials take initiatives without direct guidance from Baghdad.

F-6. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contracts a three-person team of civilian specialists to provide training and technical assistance programs. These programs aim to improve the efficiency of provincial governments. They do this by providing policy analysis, training, and technical assistance to national ministries, their provincial representatives, provincial governors, and provincial councils. The team of civilian specialists works directly with provincial officials to increase competence and efficiency. For example, they help provincial council members conduct meetings, develop budgets, and oversee provincial government activities. The team also encourages transparency and popular participation by working with citizens and community organizations, hosting conferences, and promoting public forums.

F-7. The USAID team contains members with expertise in local government, financial management, and municipal planning. Up to 70 percent of the contracted staff members come from regional countries and include local professionals. Additional contracted experts are on call from regional offices. The USAID

requires contract advisors that speak the host-nation language and possess extensive professional experience. USAID-trained instructors present training programs based on professionally developed modules in the host-nation language. The training and technical assistance programs emphasize practical application with focus areas in computers, planning, public administration, and provision of public services.

SECURITY

F-8. The absence of security impacts the effectiveness of PRT operations and efforts to develop effective local governments. Provincial governors and other senior officials may be intimidated, threatened, and assassinated in limited or unsecured areas. Provincial councils may potentially reduce or eliminate regular meetings if security deteriorates. Additionally, provincial-level ministry representatives could become reluctant to attend work because of security concerns. PRT personnel and local officials may lose the ability to meet openly or visit provincial government centers and military installations in limited security environments. During security alerts, PRT civilian personnel may be restricted to base, preventing interaction with host-nation counterparts. Unstable security situations limit PRT personnel from promoting economic development by counseling local officials, encouraging local leaders and business owners, and motivating outside investors.

F-9. Moving PRT personnel with military escorts contributes to the overall security presence. However, the PRT does not conduct military operations nor does it assist host-nation military forces. The only security role assigned to a PRT is protection; military forces provide vehicles and an advisor to escort PRT

personnel to meetings with local officials. Military personnel assigned to escort civilian PRT members receive training in protecting civilian PRT personnel under an agreement with the Department of State. The training is designed to reinforce understanding of escort responsibilities and to avoid endangering PRT

civilian personnel. Military forces escorting PRT personnel should not combine this responsibility with other missions. The problem of providing PRT civilian personnel with security is compounded by competing protection priorities. Such priorities often prevent dedicated security teams in most situations limiting security teams to available personnel.

RECONSTRUCTION

F-10. The USAID representative of the PRT is responsible for developing the PRT economic development work plan including its assistance projects. The PRT emphasizes the construction of infrastructure, including schools, clinics, community centers, and government buildings. The PRT also focuses on developing human capacity through training and advisory programs.

F-11. A PRT, such as those operating in Afghanistan and Iraq, receives $10 million in U.S. military Commanders’ Emergency Response Program funding in addition to project funds from USAID programs.

Funds and financing for microcredit projects from the Commanders’ Emergency Response Program are necessary to build host-nation capacity and strengthen the legitimacy of the governance. U.S. funds and other sources of outside funding are vital; however, host-nation governments should budget for the long-F-2

FM 3-07

6 October 2008

Provincial Reconstruction Teams

term financing of most projects. The PRT exists to encourage central ministries in distributing funds to provincial representatives. These funds are for project implementation, including accountability and management of funds.

F-12. Provincial reconstruction development committees (PRDCs) prioritize provincial development projects and ensure the necessary funding for economic progress. The PRDC was developed before the creation of the current PRT structure. The PRDC contains a USAID representative, a civil affairs advisor, one or more PRT members, and host-nation officials. A PRDC develops a list of potential projects after consulting with the national ministries, provincial authorities, and local citizens. It aims to coordinate projects with both national and provincial development plans. The PRDC examines possible funding sources to determine how project funding will be provided.

F-13. The PRT provincial program manager (a Department of State employee) works with the PRDC to review projects and determine compliance with project funding guidelines. The PRT engineer reviews construction projects to determine their technical feasibility. The list of projects is presented in a public forum to the provincial council for approval following PRDC deliberations. The list is presented to the host-nation coordination team. This team circulates the project list for final review and funding priority. A PRT has limited involvement in project implementation following project selection.

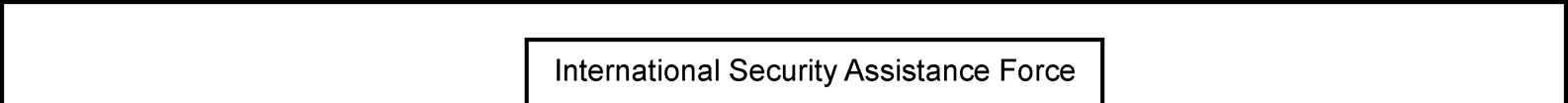

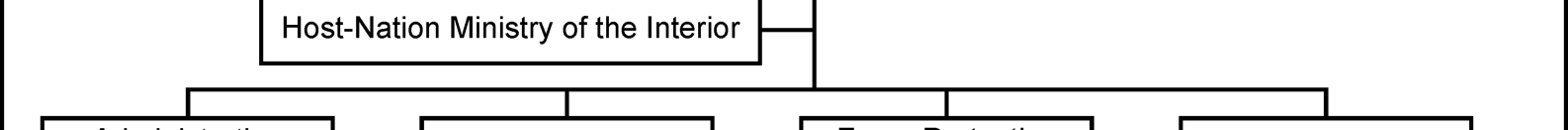

STRUCTURE OF PROVINCIAL RECONSTRUCTION TEAMS

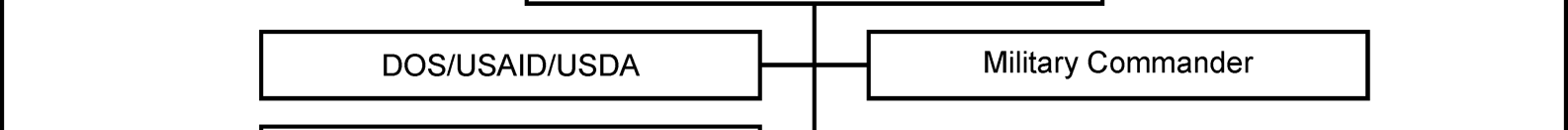

F-14. The PRT structure is modular in nature with a core structure tailored to the respective operational area. A typical PRT contains the following personnel: six Department of State personnel; three senior military officers and staff; twenty Army civil affairs advisors; one Department of Agriculture representative; one Department of Justice representative; three international contractors; two USAID

representatives; and a military or contract security force (size depends on local conditions). The size and composition of a PRT varies based on operational area maturity, local circumstances, and U.S. agency capacity. (See figure F-1.)

Figure F-1. Example of provincial reconstruction team organization

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

F-3

Appendix F

F-15. The PRT structure normally has sixty to ninety personnel. A PRT is intended to have the following complement of personnel:

PRT team leader.

Deputy team leader.

Multinational force liaison officer.

Rule of law coordinator.

Provincial action officer.

Public diplomacy officer.

Agricultural advisor.

Engineer.

Development officer.

Governance team.

Civil affairs team.

Bilingual bicultural advisor.

F-16. PRT civilian personnel normally serve twelve months, while civil affairs and other advisors may serve from six to nine months. Changes in personnel often result in changes in PRT objectives and programs. Ensuring continuity between redeploying personnel and new arrivals maintains project priorities and prevents unnecessary program termination and restart that expend time and resources and deprive the local populace. Department of Defense support of PRTs is contingent upon approval of a formal request for forces initiated by Department of State.

STAFF FUNCTIONS

F-17. PRT operations differ depending on location, personnel, environment, and circumstances. PRT

personnel perform specific tasks to support reconstruction and stabilization.

F-18. The team leader is a senior U.S. foreign service officer. This leader represents the Department of State and chairs the executive steering committee responsible for establishing priorities and coordinating activities. The team leader is a civilian and does not command PRT military personnel, who remain subordinate to the commander of multinational forces. This leader meets with the provincial governor, the provincial council, mayors, tribal elders, and religious figures and is the primary contact with the host-nation coordination team and American embassy officials. The team leader builds relationships with host-nation institutions and monitors logistic and administrative arrangement.

F-19. The deputy team leader is typically an Army lieutenant colonel who serves as the PRT chief of staff and executive officer. This officer manages daily operations, coordinates schedules, and liaises with the forward operating base commander on sustainment, transportation, and security. The deputy team leader is the senior representative of the commander of multinational forces. This leader approves security for PRT

convoys and off-site operations.

F-20. The multinational force liaison officer is a senior military officer responsible for coordinating PRT

activities with the division and forward operating base commander. These activities include intelligence, route security, communications, and emergency response in case of attacks on convoys. The liaison officer tracks PRT movements and coordinates with other military units in the operational area.

F-21. The rule of law coordinator is a Department of Justice official responsible for monitoring and reporting the local government judicial system activities. The coordinator leads the rule of law team consisting of civil affairs and local government personnel. This coordinator visits judicial, police, and corrections officials and reports local conditions to the American embassy. The rule of law coordinator advises the embassy on response measures to local government problems. This coordinator also provides advice and limited training to local government officials. The program emphasizes improvement of court administration, case management, protection of judicial personnel, training of judges, and promotion of legal education. Rule of law coordinators meet with corrections officials to monitor and report on prison conditions and the treatment of prisoners. However, in Iraq, the rule of law officer works for the MultiF-4

FM 3-07

6 October 2008

Provincial Reconstruction Teams

National Security Transition Command–Iraq. The officer manages training and assistance for police, courts, and prisons without reference to a PRT.

F-22. The provincial action officer is a Department of State foreign service representative and primary reporting officer. This officer meets with local authorities and reports daily to American embassy officials on PRT activities, weekly summaries, analysis of local political and economic developments, and meetings with local officials and private citizens. The provincial action officer assists others in the PRT with promoting local governance. Political and economic reporting by the PRT Department of State officers provides firsthand information on conditions outside of forward operating base.

F-23. The public diplomacy officer is a Department of State foreign service officer. This officer is responsible for press relations, public affairs programming, and public outreach through meetings between the PRT and local officials. The public diplomacy officer also escorts visitors to the PRT and its operational area.

F-24. The agricultural advisor is a representative of the Department of Agriculture. The agricultural advisor works with provincial authorities to develop agricultural assistance programs and promote agriculture-related industries. Agricultural advisors are volunteer representatives recruited from each agency of the Department of Agriculture to serve one-year tours. The Department of Agriculture tries to match its personnel specialties to the specific needs of each PRT.

F-25. The engineer is a representative of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The engineer trains and advises host-nation engineers working on provincial development projects. The engineer assists the PRT

with project assessments, designing scope-of-work statements for contracts with local companies, site supervision, and project management. The engineer advises the team leader on reconstruction projects and development activities in the province.

F-26. The development officer is a USAID representative. The development officer coordinates USAID

assistance and training programs and works with provincial authorities to promote economic and infrastructure development. This officer coordinates development-related activities within the PRT and supervises locally hired USAID staff.

F-27. The governance team is under a USAID contract. A contracted organization provides a three-person team that offers training and technical advice to members of provincial councils and provincial administrators. These small teams aim to improve the operation, efficiency, and effectiveness of provincial governments. The team provides hands-on training in the provision of public services, finance, accounting, and personnel management. Contracted personnel take guidance from the USAID representative but function under a national contract administered from the American embassy. The contracted organization maintains offices (nodes) that can provide additional specialists on request in major cities.

F-28. The civil affairs team represents the largest component of the PRT with Army civil affairs advisors performing tasks across each area of PRT operations. Civil affairs advisors are mostly military reserve personnel on temporary duty; they represent a broad range of civilian occupations. The PRT makes special efforts to use these personnel in areas where their civilian specialties apply. For example, a civil affairs reservist who is a police officer in civilian life is normally assigned to the PRT rule of law team.

F-29. The bilingual bicultural advisor is typically a host-nation expatriate with U.S. or coalition citizenship under contract to the Department of Defense. This advisor serves as a primary contact with provincial government officials and local citizens. The bilingual bicultural advisor advises other PRT members on local culture, politics, and social issues. Advisors must possess a college degree and speak both English and the indigenous language of the operational area.

OPERATIONS

F-30. A PRT resides at a forward operating base and operates within a brigade combat team’s operational area. A PRT relies on the maneuver unit capabilities for security, transport, and sustainment. The brigade combat team provides available military assets to the PRT under an agreement between the American embassy and the multination force. The military assets and personnel enable convoy movements for PRT

personnel.

6 October 2008

FM 3-07

F-5

Appendix F

F-31. Security operations are not a Department of State capability. Normally, military forces take the lead while operating in the current post-conflict environment characterized by continuing violence. For example, in Iraq, the military directs operations and the PRT is embedded within a brigade combat team’s operational area. The PRT maintains its primary functions—governance, security, and reconstruction—as a Department of State competency. In Afghanistan, military officers lead a PRT. The Department of State and other civilian agencies have an essential role in the operation of the PRT, but military leadership provides unity of command.

F-32. The PRT must possess a clear concept of operations, objectives, and guidelines following a period of experimentation. This effort must include a delineation of civil-military command authority within a PRT, including the supervision of contractors. These measures should also be coordinated with coalition partners so they are consistent with the operational concepts that govern the PRT.

F-33. Priority assignments and specialized training produce better teams than volunteers and on-the-job learning. A PRT often operates in stressful, uncertain, and dangerous environments. PRT assignments require officers with the proper rank and experience. This applies to USAID and other civilian agencies.

Employing retirees, junior officers, or civil affairs advisors as substitutes for civilian experts limits competence and reduces effectiveness. Contractors are not designed to permanently replace Federal representatives, despite their training or level of expertise. A PRT requires Federal employees with an understanding of Federal agency function and knowledge of requirements necessary to influence and deliver project results. Junior officers bring energy and enthusiasm but may not have the same impact as veteran government employees, especially in the areas of languages and social and cultural expertise.

SUMMARY

F-34. A PRT is an essential part of a long-term strategy to transition the functions of security, governance, and economics to provincial governments. It is a potential combat multiplier for maneuver commanders performing governance and economics functions and providing expertise to programs designed to strengthen infrastructure and the institutions of local governments. The PRT leverages the principles of reconstruction and development to build host-nation capacity while speeding the transition of security, justice, and economic development to the control of the host nation.

F-6

FM 3-07

6 October 2008