CHAPTER VII

ELABORATING THE MONOPLANE

IT is surprising to find how far the pure monoplane form has been developed by the builders of model aëroplanes. It is no exaggeration to say that they have carried some principles of construction even further than the builders of the large man-carrying monoplanes. Since a model is so easily built, and costs so little, it is of course possible to experiment with all sorts of new forms. A great many of these will doubtless prove to be all wrong, but some are certain to be valuable discoveries. In future years, when the aëroplane has been perfected and perhaps plays an important part in commerce, sport and warfare it will probably be possible to trace back many of its improvements to the model aëroplanes designed, built and flown by American boys of to-day.

A beautiful model of a pure monoplane form carefully elaborated is shown in Plate 7. In this case increased stability is obtained by throwing out additional planes both to the front and rear. It may appear at first glance that these stability-planes are very small compared with the broad soaring-plane, but they have not proved so in flight. It will be remembered that the elevating-plane of the Wright machine is very small compared with the spread of the main wings. There is besides a great advantage in placing the stability plane well forward since it makes it possible to build an unusually long motor-base and install longer and more powerful motors.

The main plane is one of the best examples of construction work to be found among all these models. It is well proportioned and the curve has been skilfully drawn. The plane is made unusually rigid by a series of supports or braces run both horizontally and vertically. Such a plane calls for considerable time and patience, but it will well repay the builder by the long and steady flights it insures for the model. In adding ribs to a large plane of this kind a convenient material may be prepared by splitting up thin wooden plates or dishes, such as you buy at the grocers for a penny. The strips obtained in this way may be easily glued or tied to the edge of the plane and shaped as desired.

A long, straight flight is insured for this model by equipping it with three vertical rudders or guiding-planes. The first rudder is well placed above the front plane. The second performs a good service beneath the main plane, while the third is carried unusually far back behind the propellers. The problem whether a rudder is more effective above or below the planes is very ingeniously solved in this case by placing them in both positions. An interesting principle is involved in placing the rear rudder. By fixing it far behind the center of gravity of the model a considerable leverage is obtained, and a small, light rudder becomes more effective in this position than a much larger plane placed forward. These rudders are built so that they may be easily turned from side to side and fixed rigidly at any angle.

PLATE IV.

One of the Simplest of Aëroplanes to Construct.

Still another interesting feature of this model is the design of the skids. The model is supported at an angle which enables it to rise easily. These skids are besides arranged with shock-absorbers, simply constructed with elastic bands, which enable them to take up the shock on landing and thus protects the machine. This is an interesting field of experiment and a little care in building these skids will save many a smash-up.

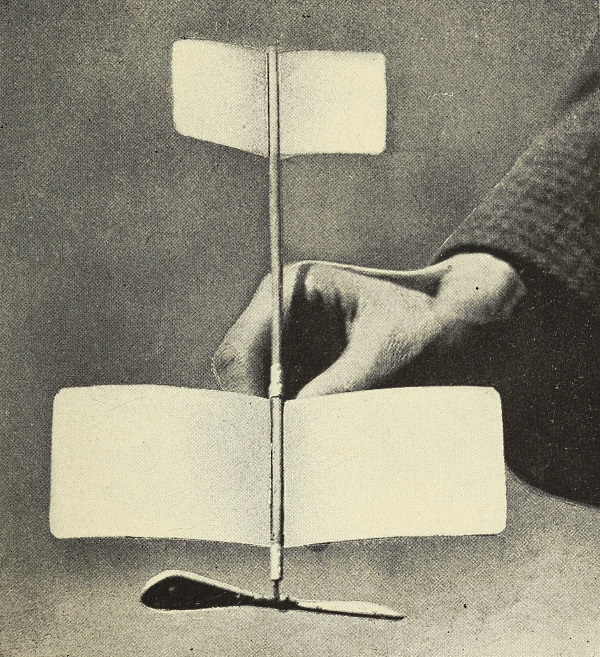

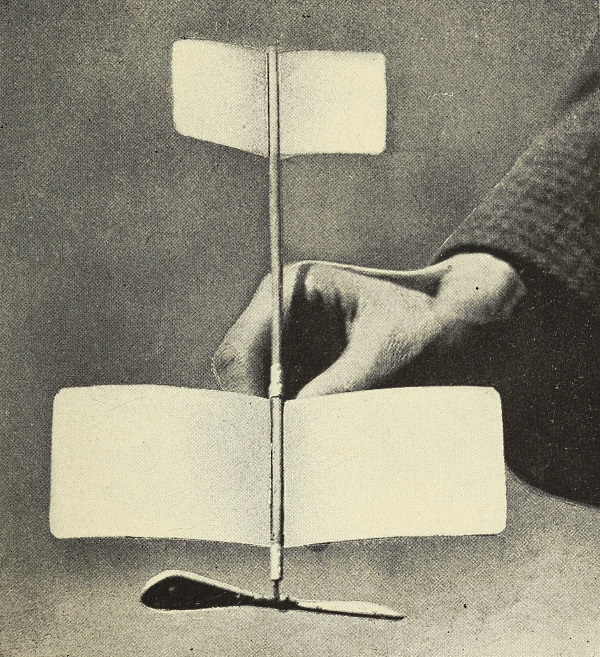

It cannot be too often stated, that the supporting power of the planes depends far more upon their shape than their size. A remarkably effective model may be made with planes, which are little more than blades (Plate 8). The planes, in this case, are made of white wood, slightly curved. The front or entering edge is very sharp, while, at the rear, a thin strip of shellaced silk is glued, thus forming a good soaring blade. The front plane is a counterpart of the first, except that it is smaller. The only stability plane is a thin, knife-like strip placed vertically just before the rear plane. The model is mounted on skids. It is driven by a small propeller placed far back of the center of gravity. It is probably the easiest as it is the smallest of all models to construct, and will fly for more than three hundred feet.

In building this model it will be found a good plan to bend the strips of wood for the planes by steaming them over a kettle. Allow the steam to play on the under or concave side of the plane. When dry the plane will retain its shape. The front or entering edge should be trimmed away to a sharp line and sand-papered perfectly smooth. The front corners of the planes should be slightly rounded while the rear edges are kept straight. The forward plane should be tilted slightly upward to enable it to rise, but at an angle of less than thirty degrees. The secret of the remarkable flights of this model probably lies in the smoothness of its planes and the absence of irregular parts which offer a resistance to the air.

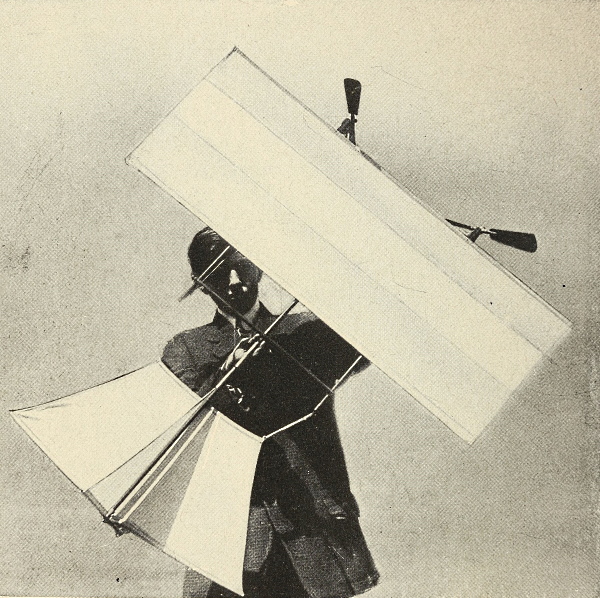

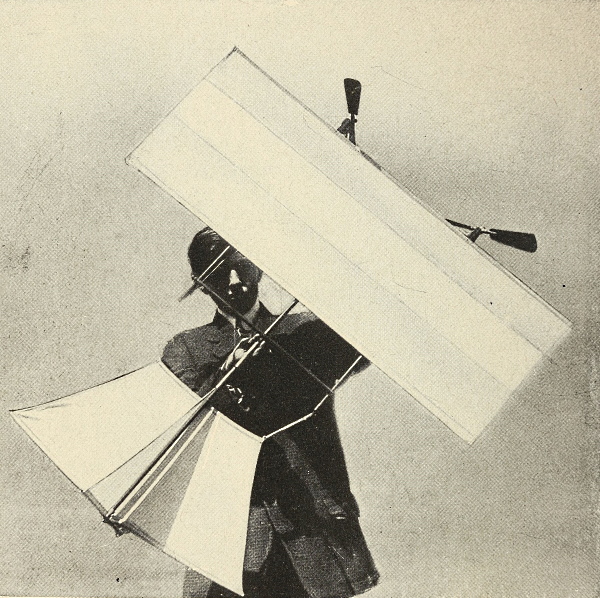

An interesting field of experiment, as yet almost untouched, lies in the triangular, or narrow-prowed forms of aëroplanes (Plate 9). The theory of this model is, that a triangle entering the air end-wise, will meet with less resistance than when presenting a broad, entering edge. The model is, frankly, an experiment, although it has been found to have unexpected stability, and flies well. Its central planes, joined at right angles, is supported by two, lateral, stability-planes, radiating backward from the front of the model. The aëroplane is drawn, not pushed, through the air, by double propellers, and is steered by an angular guiding-plane at the rear. The planes are mounted upon a triangular frame, which runs on wheels, two being set forward and one aft. The planes, taking advantage of the dihedral angle, seem to rest upon the air, which makes for stability. In actual practice, however, the planes in this particular model have been found to be too narrow. The question naturally arises as to the effect of reversing this model and turning the dihedral angle of the central plane, into a tent effect. As a matter of actual experience, the model flies almost equally well upside down.

In many of the early attempts to build aëroplanes the wings or planes were tilted sharply upward from the center thus forming what is known as a dihedral angle. This form served to lower the center of gravity and, it was thought, made for stability. The Wright Brothers found that this plan, although it lowered the center of gravity, caused it to move from side to side like a pendulum, and therefore abandoned it in favor of the flat curved wing which have been so generally imitated. Now this model returns to the old principle of the dihedral model, but treats it in a new way. By building the model with three planes, each with the dihedral angle, the center of gravity has been lowered and, at the same time, the oscillation has been greatly reduced.

PLATE V.

Too Large for Beginners, but Will Make Long Flights.

The narrow-prowed form of this model is also very interesting and its principle may well be copied. All of the successful monoplanes aloft to-day, the Bleriot, Santos Dumont, Antoinette and others are driven with their larger or soaring planes forward and their smaller stability-planes in the rear. The day may come when these machines will be reversed. The model before us may point the way to a great improvement in the building of air-craft. It is an important principle for the builder of model aëroplanes to bear in mind.

In the present state of model aëroplane building, the longest flights are made with an adaptation of the monoplane forms. An excellent model is shown in Plate 10. The dihedral, or V shape of the planes gives them greater supporting power than others in the horizontal position. The stability plane beneath is particularly recommended, since it utilizes the frame already in position and does not add to the weight of the model. The rear of this plane, which is hinged, is easily adjusted.

The planes of this model are especially interesting. They are made of silk, laid over frames of dowel sticks, and each pair is held tightly together by the simple device of connecting them with elastic bands, attached to clasps. The wires running to the corners of the planes, are fastened to small brass rings which may be slipped over the sticks or posts in the center of the frame, which makes them very simple to adjust. It will be noticed that the rear part of each plane swings freely, and is kept in place only by corset steels, used as ribs, which are sewn into the cloth. These floating or soaring blades, as they are sometimes called, insure longer flights.

With such a model there is little danger of building a too powerful motor. By increasing the size of the wings, and careful weighting, a surprising amount of power may be applied to such a model without rendering it unstable. This is of course a great advantage in such a model, since it lends itself to longer flights and the installation of comparatively heavy motors. When you find yourself with a model of this design in good working order, experiment by binding the wings or planes at the middle to form an arched surface like the wings of a sea gull. The flying radius of some of these models has been increased fully fifty per cent by this simple expedient.

An interesting modification of this form (Plate 11) is provided with rigid wings, and is driven by a single propeller. The very simple but effective method of bracing the wings, may be studied to advantage. The skids are well designed. In still another type of this general monoplane form (Plate 12) the propeller is placed in front of the planes, and the rubber motor runs below the main bar. The wheels supporting this model are particularly well made.

A very serviceable, little monoplane form may be made by making the rear upper plane adjustable (Plates 13-14). The front plane is V-shaped and is unusually stable for so light a model. By tilting the rear plane up or down, a good level flight may be obtained. The frame, in this case, is made of wire. The propeller is placed well behind the rear plane, thus bringing the center of gravity well forward to balance the angle of the rear plane. The blades of the propeller are made of twisted wood, which is not to be recommended, since it is likely to lose its shape.

In Plates 15-16 we have a well thought out little monoplane, which well repays study. The propeller is set forward of the lifting plane which is the larger of the wings. The rear plane may be tilted up or down. The rudder, which is also adjustable, is set below it. The arrangement of skids is excellent, enabling it to rise from the ground with little loss of friction. The method of flexing the front plane may well be imitated.

Model shown in Plate V. Ready for a Flight.

A good working idea of the aëroplane is clearly shown by the builder of the biplane with triangular wings (Plate 17). His model is not successful and will not fly, yet it embodies several good features. The biplane form of the lifting plane is excellent in itself as we have seen in earlier models. The spacing of the two planes is good, and the bracing of the model throughout is well planned. The triangle does not make a good soaring plane even when its broad side is made the entering edge. The triangle serves well enough however for the rear stability plane. The chief fault of the model is that it is much too large. The motor although well proportioned is much too weak to propel so large a frame.

An interesting variation from the common type of aëroplane is made by varying the angle of the sides of the planes (Fig. 18). Here is a well constructed model, and, with a single exception, fairly well proportioned. The mistake, and it is likely to prove a serious one, is in the size of the vertical rudders. They are well placed above the main plane, but their size is likely to defeat the purpose for which they were designed and knock the model off its course rather than keep it steady. It is a question again if one of these rudders would not serve the purpose better than two and thus minimize weight and resistance.

The best point of this model is the ingenious method of enlarging the surface of the planes without increasing the size of the planes or adding to their weight. This is done by cutting the covering of the planes at an angle and keeping the entire surface taut by bracing. It is of course very important that the cloth should be held tight without wrinkling. The plan of having the wings taper slightly outward is good. Such a model combines more lifting surface with less weight than any other model of this general group.