CHAPTER X

FAULTS AND HOW TO MEND THEM

YOUR model, perhaps a beautiful one, finished in every part, may twist and tip about as soon as it is launched and quickly dart to the ground. The fault is likely to be in the propeller, being too large for the size and weight of the machine. This may be remedied by adding a weight to the front of the machine, by wiring on a nut or piece of metal. Should this fail to steady the aëroplane, the propeller must be cut down.

When your propeller is too small the machine will not rise from the ground, or, if launched in the air, will quickly flutter to earth. If the model on leaving your hand, with the propeller in full motion, fails to keep its position from the very start, the blade should be made larger. There is no use in wasting time and patience over the machine as it is.

Many a beginner, with mistaken zeal, constructs a too powerful motor. The power in this case turns the propeller too swiftly for it to grasp the air. It merely bores a hole in the air and exerts little propelling force. An ordinary motor when wound up one hundred and fifty turns should take about ten seconds, perhaps a trifle longer, to unwind. It is a good plan to time it before chancing a flight.

Bad bracing is another frequent source of trouble. The planes should be absolutely rigid. Test your model by winding up your motor and letting it run down while keeping the aëroplane suspended, by holding it loosely in one hand. If the motor racks the machine, that is, if the little ship is all a-flutter and the planes tremble visibly, the entire frame needs tuning up. It is impossible for an aëroplane to hold its course if the planes are in the least wabbly. The braces should be taut. A loose string or wire incidentally offers as much resistance to the air as a wooden post.

The flight of your model aëroplane should be horizontal, with little or no wave-motion. Your craft at first may rise to a considerable height, say fifteen or twenty feet, then plunge downward, right itself, and again ascend, and repeat this rather violent wave-motion until it strikes the ground. To overcome this, look carefully to the angle or lift of your front plane or planes and to the weighting.

The explanation is very simple. As the aëroplane soars upward, the air is compressed beneath the planes, and this continues until the surface balances, tilts forward, and the downward flight commences. Your planes should be so inclined that the center of air-pressure comes about one third of the distance back from the front edge. The center of gravity of each plane, however, should come slightly in front of the center of pressure. After all, the best plan is to proceed by the rule of thumb, and tilt your planes little by little, and add or lessen the weight in one place or another, until the flight is horizontal and stable.

If your aëroplane does not rise from the ground, but merely slides along, the trouble is likely to be in your lifting plane. Tilt it a trifle and try again. The simplest way to do this is to make the front skids higher than those at the back. If the front skids are too high, the plane will shoot up in the air and come down within a few feet.

The most carefully constructed model is likely to go awry in the early flights. The propeller seems to exert a twist or torque, as it is called, which sends it to the right or left, or up or down, even in a perfectly undisturbed atmosphere. It is assumed that your model is symmetrical. An aëroplane not properly balanced, which is larger on one side than the other, or in which the motor is not exactly centered, cannot, of course, be expected to fly straight. However, to be on the safe side, go all over the machine again. Measure its planes to see that the propeller is in the center. Hold it up in front of you right abeam, and test with your eye if the parts be properly balanced.

If it still flies badly askew, flex the planes by bending the ends up or down very slightly by tightening or loosening the wire braces running to the corners. At the same time add a little weight to counteract the tipping tendency. A nut or key may be wired on the edge which persists in turning up. It may require much more weight than you imagine. The difference should begin to show at once. Even after a model appears to work fairly well as a glider, the addition of the motor may so change the center of gravity that it will “cut up” dreadfully.

It will be well to leave your planes loose so that they may be shifted back and forth and not fasten them till you have tried out the motor. If you followed the plan suggested of fastening the plane to the central frame by crossing rubber bands over it, you can easily adjust them. If the model tends to fly upward at a sharp angle, slide the front plane forward an inch, and try another flight. There is an adjustment somewhere which will give the model the steady, horizontal flight you are after.

Some models will refuse to rise and swing around in an abrupt circle the moment the motor is turned on. This may be caused by the propeller being much too small for the motor. After looking over all the photographs of the models shown in these pages you will gain an idea of the proper proportion, and be able to tell offhand if the propeller is out of proportion. A small propeller revolving very rapidly, or racing, is likely to give the model a torque, even if it be otherwise well proportioned. Don’t try to remedy this with rudder surfaces, but change your propeller, or your motor, or both.

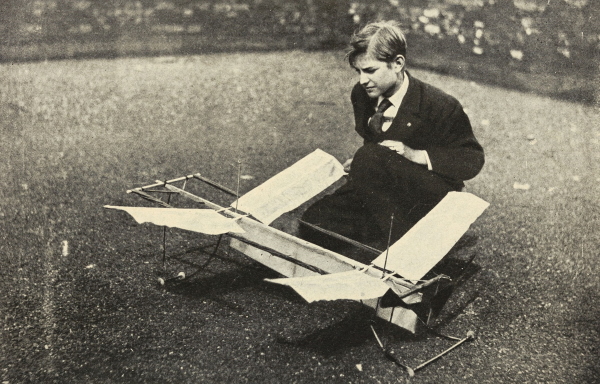

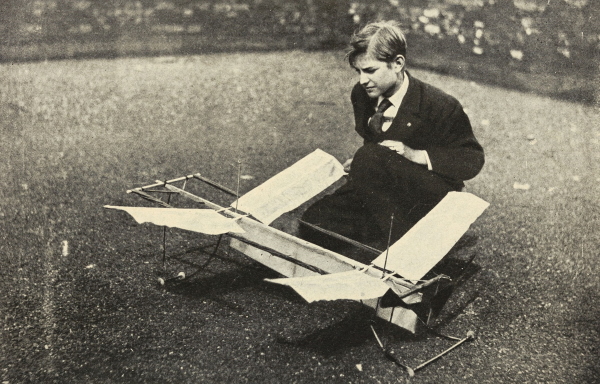

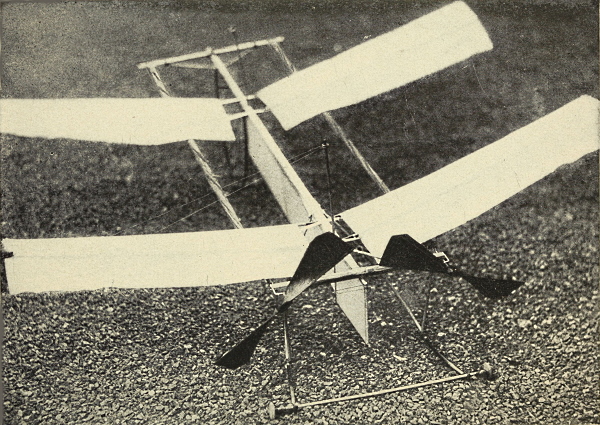

PLATE X.

An Excellent Monoplane Capable of Long Flights.

When your aëroplane turns in long, even curves to one side or the other, look to your rudder surface. Turn it to one side or the other, just as you would in steering a boat. It is, of course, obvious that it must be kept rigidly in position. If a slight turn of the rudder does not straighten out the flight, you probably need more guiding surface, and the rudder must be enlarged. If the model still continues to turn away from a straight line, tilting as it does so, try a little weight at the end of the plane which rises.

The commonest of all accidents to aëroplane models is the smashing up of the skids on landing. A model will frequently rise to a height of fifteen or twenty feet, and the shock of a fall from such an elevation is likely to work havoc in the underbody. There is no reason, however, why your model should not come down as lightly as a bird from the crest of the flight wave. The model, when properly proportioned, weighted, or balanced, will settle down gradually and not pitch violently. It is these quick darts to earth which cause the worst disasters.

A model should have sufficient supporting surface to break its fall when the motor runs down, at any reasonable elevation. If the model aëroplane falls all in a heap, as soon as the motor slows down, it will be well to look to this and perhaps increase the size of your planes. As a general rule, the biplanes or the models in which the double planes have been used, either for lifting or soaring planes, will settle down more gradually. The lateral planes, whatever their position, also lend valuable support when the critical time comes in the descent. Your model is not perfect until it falls easily at the end of the flight.

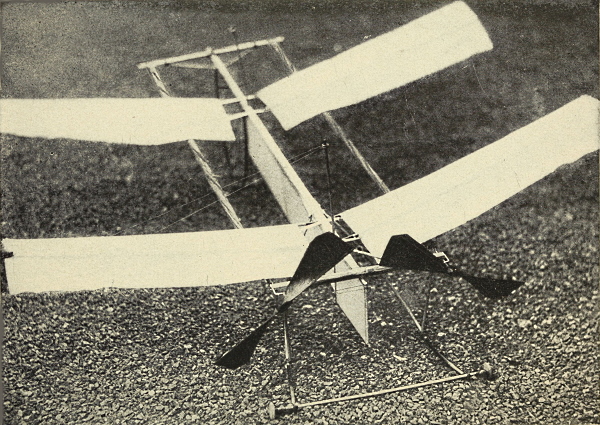

Detail of Model Shown in Plate X.

Under perfect condition, in absolutely undisturbed air, an aëroplane may be made to come down so lightly that no bones, even the smallest, will be broken. A gust of wind, however, may ruin all your calculations and bring the aëroplane down with a dislocating shock. The skids must be designed to meet extreme conditions, the worst that can possibly befall. It has been pointed out that these skids or supports should be high enough to give the propeller clearance so that the propeller blades will not touch the ground. By using a light flexible cane for the purpose, and bending them under, a spring may be formed which will take up the shock of a violent landing. Some builders go further and rig up the skids with braces of rubber bands to increase this cushion effect. A variety of constructions are shown in the photographs of the various models. Your skids should enable your model to withstand any ordinary shock of landing, without breakage of any kind.

The life of your motor can be greatly increased by careful handling. The rubber strands are likely to be worn away against the hooks at either end. The wire used for the hooks should be as heavy as possible to keep it from cutting through. Be careful that the wire which comes in contact with the rubber is perfectly smooth and flawless. A little roughness or a spur on the wire will soon cut through the rubber. It is a good plan to slip a piece of rubber tubing tightly over the hook and loop the rubber bands of your motor over this cushion.

The first break in the rubber bands is likely to come near the center of the strand. A number of loose ends appear. The broken ends should be knotted neatly and the loose ends cut away. If the strands come in contact with any part of the motor base, a breaking will quickly follow, and your strands soon become covered with a fringe of loose ends. Be careful to tie up all loose ends and trim them away, since the ends in twisting serve to break other strands. Although the finer strands of rubber give the greater thrust, do not buy them too small, since they are easily broken.

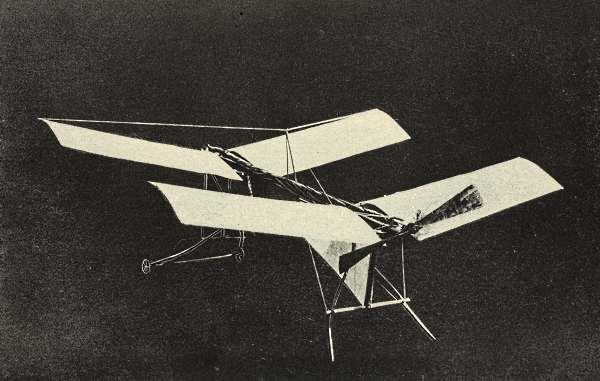

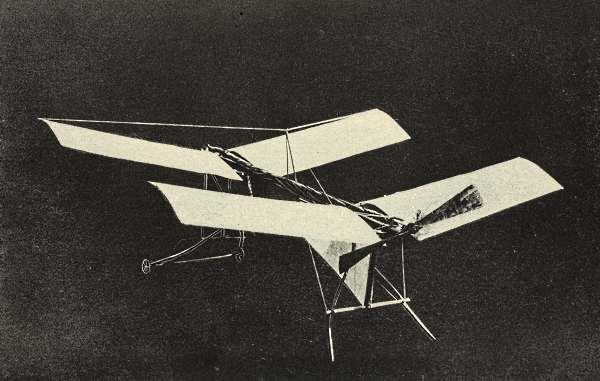

PLATE XI.

A Well Thought Out Monoplane.

The length of your motor base beyond the front plane should be carefully calculated. It is very easy, of course, to run your shaft too far forward. The center of gravity is easily shifted in this way, and your model soon becomes unmanageable. An aëroplane with this fault will not rise, but merely pitches forward under the thrusts of the motor. It is almost useless to attempt to balance this by weighting the machine. The front plane should be placed further forward, and if the lifting surface does not seem sufficient, cut away the front of your motor base, once for all. A too short motor base, on the other hand, will cause your model to shoot upward at a sharp angle, and waste much valuable propelling power before it rights itself and takes a regular horizontal flight.

In the model aëroplane there is only one point where friction affects the flight, namely, along the propeller shaft. One can hardly be too careful in the construction of the axle. The thrust of the rubber at best, is limited, and this power must be exerted without loss of any kind. A faulty propeller shaft will use up a surprising amount of energy. Your rubber motor should unwind to within one or two turns.

Bear in mind that one of four things is likely to be responsible for your trouble. The planes may not be properly placed on the frame, they may not be properly flexed, they are not set at the proper angle of elevation, or your motor is at fault. Watch these points, and you will soon have your machine under perfect control. In the extremely complicated models it is often difficult to locate the fault. Build your model so that these parts may be adjusted in a moment without taking apart. After you have built an aëroplane model, even a very simple one, the pictures of other aëroplanes will have a new meaning for you. Every new model you see will give you some new idea. A number of the most successful aëroplane models in the country are shown in the accompanying photographs. Study these carefully, and you will learn more from them of practical aëroplane construction than from any amount of reading.