CHAPTER IX

COMBINING MONOPLANE AND BIPLANE FORMS

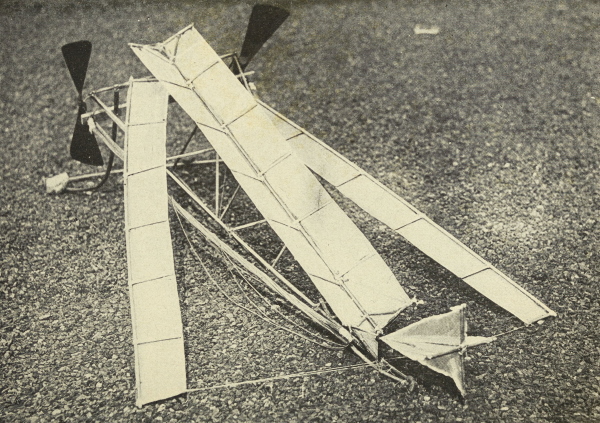

ALTHOUGH the regular biplane form is exceedingly difficult to manage in small models, there is great advantage in combining it with the monoplane forms (Plate 26). The biplane makes an excellent lifting plane, and when the model combines with it a broad monoplane for stability, surprisingly long flights may be made. The model here illustrated has flown 218 feet 6 inches.

Despite its size, the model is exceedingly light. It is made almost entirely of dowel sticks braced with piano wire. Still another advantage of the biplane form is the action of the supporting surface when it comes to descend. The model settles easily to the ground, in contrast to many monoplane models which come down with a dislocating shock. The skids of this model are simple and effective. In a model of this form it is obviously best to have the propellers drive rather than pull it.

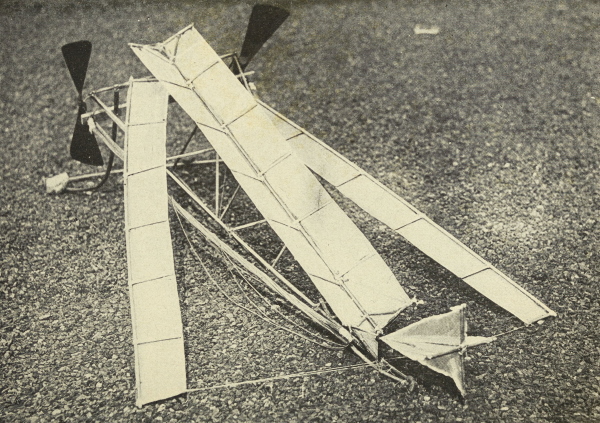

An ingenious young aëronaut has reversed the above order and placed his biplane in the rear, using the monoplane for lifting (Plate 27). His model is unusually large, having a spread of four feet. The biplane is square, with lateral stability planes on either side. The elevating planes appear small in proportion, but they serve to keep the craft on an even keel. The most striking feature of this model is its extreme lightness. Although unusually large, it weighs but nine ounces. The frame, except for the braces is built of reed. The planes are covered with parchment. The model is driven by two rather small propellers. The position of the propellers will appear, at first glance, to be rather low, but it must be remembered that the extreme lightness of the model brings the center of gravity very far down. The model has flown more than two hundred feet.

PLATE IX.

An Interesting Experiment Along New Lines.

The stability of the models thus combining the monoplane and biplane forms comes as a surprise. Both the models in question rise easily from the ground, which is more than can be said of many aëroplanes big or little, and once aloft maintain a steady horizontal flight, which is still more unusual. An interesting field of experiment is suggested by these combinations. These successful experiments have been made with perfectly flat planes. Suppose now we try them out with flexed planes. If the stability thus gained may be combined with the increased soaring quality of the curved plane, we may be on the way to making some remarkable flights. In the summer of 1909 a number of boys built and flew model aëroplanes in New York, when many interesting and well constructed models were brought out, and the longest flight was only sixty feet. Less than one year later the same boys succeeded in flying their machines for more than two hundred feet. The new models were no larger, the motors no more powerful, but the machine had become more shipshape and efficient. It is reasonable to suppose that each year will bring a similar advance.