CHAPTER IV

ABOARD THE WRIGHTS’ AIRSHIP

SEEN high aloft the Wright aëroplane appears so graceful and fragile that its actual dimensions come as a surprise. In the upper air it seems no larger than a swallow, but, as it settles to earth, the wings lengthen out to the width of an ordinary street.

There is some good reason for each stick and wire, and for every twist and turn of the Wrights’ marvellous airship. When one considers what wonderful feats this aircraft performs, its form and mechanism seem extremely simple. It is far less complicated than any locomotive or steamship, and the action of its planes is far easier to explain than the sails of an ordinary seagoing ship. When one has once gone over the fascinating little craft, all other aëroplanes, which more or less resemble it, may be readily understood.

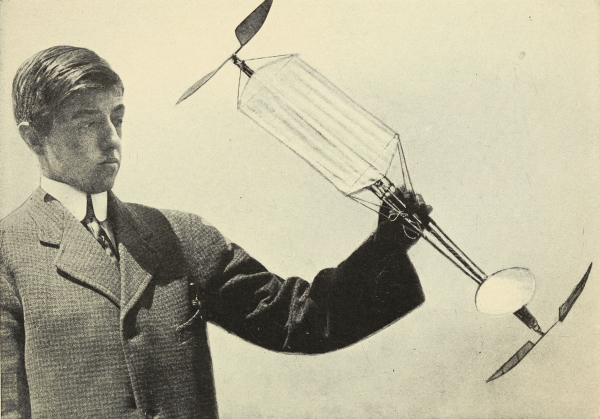

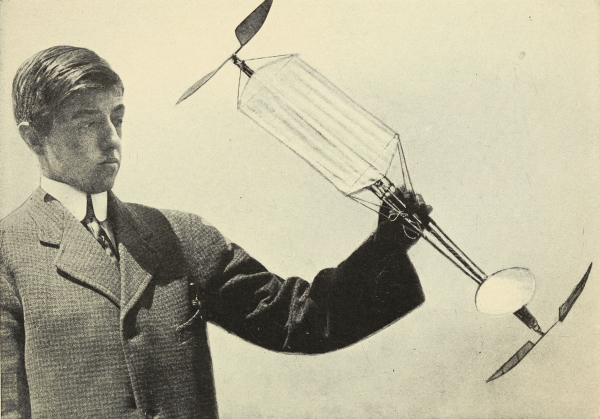

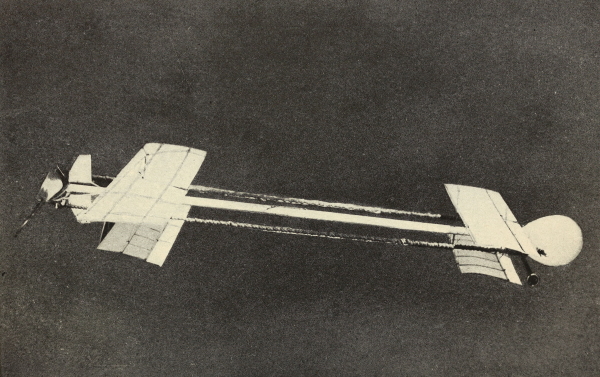

PLATE XXII.

An Interesting Form which Flies Backward or Forward.

The Wright machine was not only the first power airship to fly and carry a man aloft, but for all its rivals, it still rides the unstable air currents more steadily than any other. The planes measure forty feet from tip to tip, six and a half feet across, and are spaced six feet apart. The distance between the planes is very important and was only fixed after a number of experiments. The area of the wings or supporting surfaces is 540 feet, which is considerably more than in most airships. The machine complete, without any passenger or pilot, weighs 880 pounds, although you would imagine it to be much less. The two propellers measure eight feet in diameter, and turn at the rate of 450 revolutions a minute. Equipped with a four cylinder engine of from 25 to 30 horse power, the airship has a speed of forty miles an hour, which is often increased when traveling with the wind.

The seats for the pilot and the passenger are placed at the center at the front of the lower plane, so that their feet hang over the front or entering edge. The passenger sits very comfortably throughout the flight. There is a back to lean against, a brace for the feet, while the struts between the planes give every opportunity to hold on. In some of the models these seats are even upholstered in gray to harmonize with the silver or aluminium paint of the machine.

A second and smaller biplane, which serves both as rudder and lifting plane, extends about ten feet in front of the main planes. These two planes, which have a combined area of eighty square feet, may be inclined upward or downward by touching a lever at the pilot’s seat. The motor, radiator and petrol or fuel tank are placed on the lower plane in the center of the machine so that they balance the weight of the pilot and the passenger. The weight of the lifting planes and rudders rests on the main planes or lower deck.

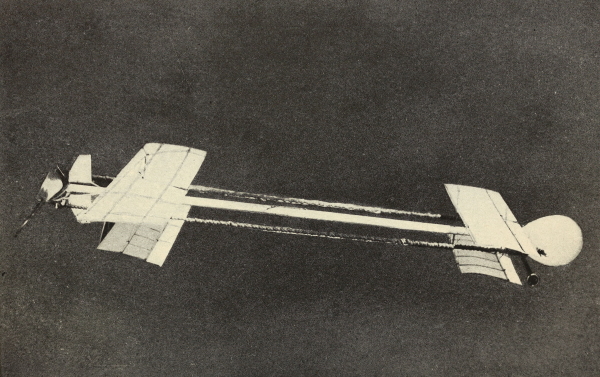

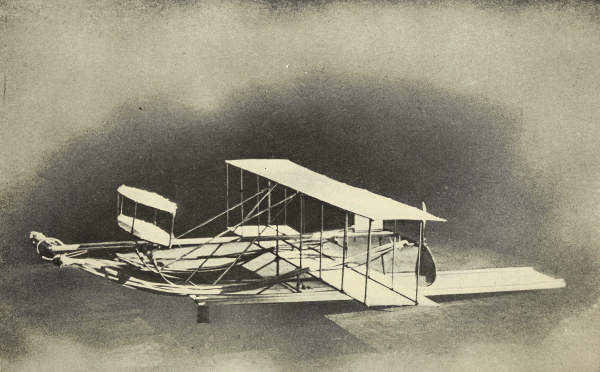

PLATE XXIII.

A Well Built Model Badly Proportioned.

The most interesting feature of the Wrights’ airship is, of course, the method for flexing the tips of the wings or planes to imitate the flight of the birds. The ends of the large planes are made slightly flexible, and may be turned up or down by moving a lever placed convenient to the pilot’s hand. Both planes are flexed, or turned up or down, at the same time the vertical rudder moves, so that, when the aëroplane turns to right or left, the wings give the machine the proper balance. If it were not for this arrangement, the ends of the planes in turning would tend to rise, since they travel the faster, and the machine would be in danger of upsetting. The ends of the planes may also be flexed separately when the machine is in straight flight, whenever it becomes necessary to balance it against a dangerous air current or a gust of wind. The pilot, it will be seen, has every point of the great machine, as it were, at his finger ends.

The marvellous power placed in the hands of the pilot of one of these models makes him almost equal of the birds soaring about him. Let us suppose an accident to occur. Even should the engine stop, the skillful pilot is still master of the situation. He can actually coast down to the ground on the air with comparative safety. Mr. Orville Wright has soared up 3000 feet and, after stopping his propeller, slid down on nothing at all, at the rate of more than twenty miles an hour, by the force of gravity alone.

The Wright method of alighting is also borrowed from the birds. Watch any bird alight on a twig, and you will see that it always settles on the top of the twig, which is pressed straight down by its weight, and never sideways. As the Wrights come down, they approach to within a few feet of the earth, but, without touching they swoop up again, and finally settle down from a height of only a few feet. Considering the weight of their machine, they actually come down as lightly as a bird. While traveling at a speed of forty miles an hour they will skid along the ground or come to rest within five or six feet, so quietly that a passenger cannot tell when he lands.

No part of the aëroplane calls for more clever workmanship than the wings or planes. They must be so thin and light that they will ride the air like the wings of a bird, and yet strong enough to support the weight of hundreds of pounds of machinery and of passengers. In the Wright model, the planes are made entirely of wood, but so ingeniously braced that they are perfectly rigid. The building of such a wing is especially difficult, since it must be curved with scientific accuracy. In the Wright model machines, as in all aëroplanes, the curve is upward, with the highest point of the arch near the front or entering edge.

Both sides of the frame are completely covered so that they may offer the least possible amount of resistance. There is not a ridge, scarcely a seam, to catch the air. A stout canvas is used for covering. The ingenuity of these clever workmen led them to lay on the cloth with the thread running diagonally, at an angle of forty-five degrees. This plan serves to hold the frame more closely together and keeps the cloth from bagging or wrinkling.

At the first glance, the Wright machine appears to be made entirely of aluminium. Seen high aloft in the sunlight, it appears like some delicate jewel. The effect is due to the paint. The entire framework of the machine is made of spruce pine except the curved part of the wings, or entering edge, which is of ash. The propellers are driven by chains, connected with the motor, which run in steel tubes, thus doing away with the danger of fouling by passengers or loose objects. The ignition system is operated by a high tension Eisenmann magneto machine. The petrol used for fuel is carried in a tank placed above the engines and is supplied by gravity. The two wings are connected by a series of distance rods and wire cross-stays, which keep the entire front, or entering edge, and central part of the model, perfectly rigid.

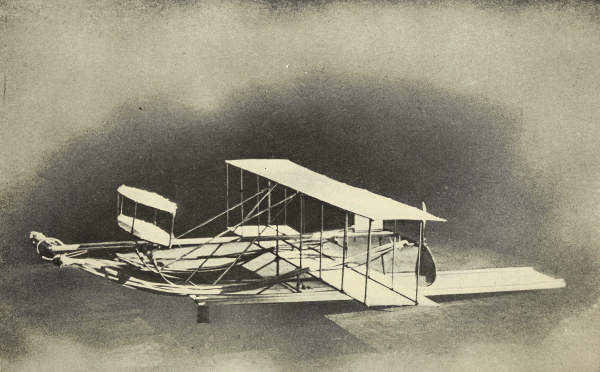

PLATE XXIV.

A Wright Model Ready for Flight.

Although nearly all the aëroplanes, nowadays, are mounted on ordinary bicycle wheels, the Wrights prefer a simple system of skids, not unlike the runners of a sleigh. One of the great advantages of the skids is the fact that they take up the shock on landing more completely than wheels and protect the machine from many a hard bump.

The airship rests on a small frame mounted on two wheels, placed tandem, and is balanced on a small trolley which runs along a rail about twenty-five feet in length. It is started by the pull of a rope attached to a 1500 pound weight, which drops from a derrick fifteen feet in height. When everything is ready, the temporary wheels are taken away, the rope is attached, and finally the weight released. The machine glides swiftly down the track, and when the necessary speed has been reached, the pilot raises his elevating planes, a trifle, and the ship glides gracefully upward and onward.