CHAPTER V

OTHER AEROPLANES APPEAR

IN the summer of 1904 the boys of Paris were greatly interested in watching a curious, giant kite in flight over the River Seine. The string of this kite was drawn by a fast motor boat, which darted along, while the kite rose high in the air. Its inventor tinkered with it, and changed its wings about until it finally flew like no other kite ever seen in France. All this was by no means mere play, however, for many scientists watched the kite as it soared about and a great deal of valuable information about the behavior of kites of this shape was learned. The man with the kite, who soon became famous in the world of aviation, was named Voisin. The aëroplane, which he afterwards built, modeled on this kite, was flown in many remarkable flights by Henry Farman, Delagrange, Paulhan, and others. Like the Wright airship, Voisin’s is a biplane or double plane model.

Although at first glance, the Voisin and Wright aëroplanes may seem very much alike, as we look more closely, we will find many points of contrast. The Voisin model has a large tail-piece, consisting of two vertical planes, which project far behind. These planes are believed to make its flight very steady. A single vertical rudder is placed between the two rear edges of this plane. The rudders are turned by horizontal, sliding bars attached to the wheels, directly before the pilot’s seat, like an automobile. The horizontal rudder in front, which corresponds to the Wrights’ double lifting plane, is single and is placed lower down than in the Wright model.

The steadiness of the Voisin aëroplane in flight is gained without flexing the planes. A series of four vertical planes connect the upper and lower wings which give the machine much the appearance of a box kite. These walls are arranged so that the space enclosed at either end is almost square. It is believed that the arrangement of these walls keeps the air from sliding off the under surface of the horizontal planes, and thus greater lifting power is obtained. It is claimed that the model has much greater longitudinal stability than the Wrights’ machine. In other words, the long tail piece prevents the machine from tipping or pitching when the wind gusts come unevenly. The box-like or cellular form, it is believed also, adds to its stability. The model holds the record for flying at the lowest speed—22.8 miles an hour. On the other hand, the Voisin model cannot, with any degree of safety, coast down on the air from great altitudes, like the Wright model.

The method of starting the Voisin airship is entirely different from the Wrights’. The machine is mounted on two wheels, attached to the girder body with an arrangement of springs to take up the shock on landing. To launch the aëroplane, the propellers are started, and the machine rushes forward on its wheels until it has developed sufficient speed to send it up. It may thus rise from an ordinarily level ground, and does not require the apparatus used by the Wrights. The pilot and passenger sit in much the same position as in the Wright aëroplane.

The Voisin model weighs 300 pounds more than the Wrights’ or 1590 pounds. It has a supporting surface of 535 square feet, and a speed, under favorable conditions, of 38 miles an hour. Another point of difference from the Wright model is the propeller, which is single and measures seven feet six inches in diameter. The motor, an eight cylinder Antoinette, usually gives fifty horse power at 1100 revolutions per minute. The Wright Brothers, by the way, make their own motors, which are considered inferior to the French motors.

The smallest and swiftest of all the aëroplanes is the Curtiss-Herring model, which was invented by two Americans whose names it bears. Its general form suggests the Wrights’ machine. The span of the large planes is only 29 feet or under, the depth but four feet six inches, and the spacing four feet six inches. It has a total wing surface of but 258 square feet. The weight, not including the pilot, is only about 450 pounds. When seen beside the aëroplane of ordinary size, the little craft looks like a very large toy model. It has the appearance of a smart little racer, however, and its maximum speed is over 50 miles an hour.

Everything has been sacrificed in the Curtiss-Herring model for the sake of compactness. The forward rudder, which seems small even for such a craft, consists of two planes, one above the other, whose combined area is only twenty-four square feet. Unlike the Wright or Voisin models, this forward rudder carries a vertical plane which makes for stability. There is no tail as in the Voisin model, and the rear, vertical rudder consists of a horizontal plane six feet wide and two feet, three inches deep and a vertical rudder below it, two feet deep and three feet four inches wide. The front and rear planes extend out from the main frame about the same distance. The main stability planes, curiously enough, are placed inside the frame. There are two of these, one at either end of the main plane.

An ingenious method has been followed to control the various planes. The pilot sits facing a wheel, like that of an automobile, which is so rigged that by simply pushing it from him or pulling it back, he may lift or decline the front planes. By turning this wheel he operates the rudder in the rear, exactly as you would steer an automobile or a boat. The balancing mechanism in turn is connected with a frame which fits about the pilot’s shoulders like a high-backed chair and is operated by merely leaning to one side or the other. This has the same effect as warping the main planes. The control of the machine becomes largely automatic. If the pilot feels that his aëroplane is tilting over at one end or the other, he merely leans to one side or the other, and, without taking his hands from the wheel before him, has the machine under perfect control. Even the motor is controlled by pedals placed under the pilot’s feet.

This little racer is mounted on three wheels, one well forward and two in the rear about half way between the main planes and the horizontal rudder. An original feature of this model is a foot brake which, connecting with the forward wheel, helps to slow down the machine on landing, just as you close the brake of an automobile. There is only one rudder measuring six feet in diameter, which is unusually large considering the size of the model. The engine is mounted at the center of the space between the two main planes, and the propeller, which is kept on a line with it, is therefore considerably higher than in most aëroplanes. The lower plane comes very near the ground. It is only raised by about the height of the bicycle wheels. It is thought by some that this arrangement of the engine blankets the propeller, while others argue that the suction produced in this way increases the thrust of the propeller. The machine is built of Oregon spruce, the wings are covered with oiled rubber silk, and the entire mechanism is beautifully finished in every detail.

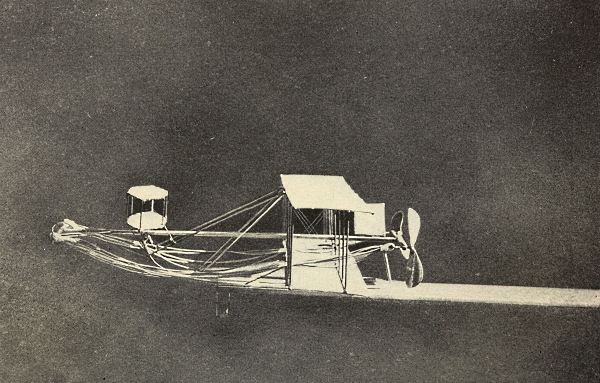

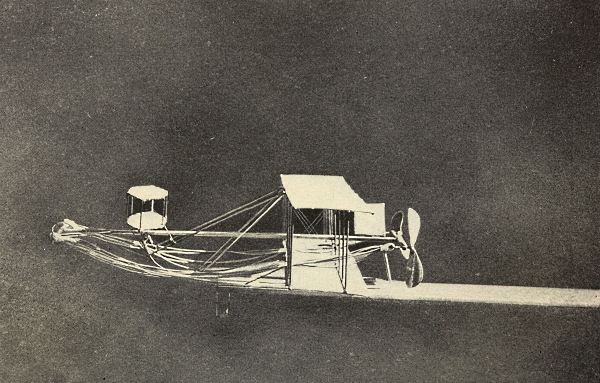

PLATE XXV.

Another View of the Wright Model.

The ingenuity of the designers of aëroplanes is astonishing. With so many aëroplanes in the field, or rather in the sky, it is surprising that they are not more alike. The Farman biplane, for instance, follows the same general proportion as the Wright machine, but there the similarity ends. To secure equilibrium in this model, four small planes are used, hinged at the back of the two main planes, and these, it has been found, take the place of the flexing device used by the Wrights. The two swinging planes on the lower wing are controlled by wires, while the upper two swing free. A single lever controls the two lower planes and the horizontal rudder.

Farman has placed his rear stability planes unusually far behind the main frame. They consist of two fixed horizontal planes, one above the other, with a vertical rudder placed in the space between them. The front horizontal rudder for vertical steering, is a single plane, mounted close to the entering edge. The vertical rudder is worked by a foot pedal. The machine is driven by one large wooden propeller, eight feet six inches in diameter, at a speed of 1300 revolutions per minute, which, it will be noticed, is unusually high. The Farman biplane is one of the heaviest yet constructed, weighing about 1000 pounds without the pilot.

An original plan has also been found for mounting the machine. The aëroplane rests upon a combination of skids and wheels. There are two sets of wheels under the front edge of the plane, while the two skids are placed between the wheels of each pair. The motor is four cylinder, fifty horse power type, and drives the machine at the rate of forty miles an hour.

The largest, and by far the heaviest aëroplane is the Cody biplane built by an American inventor who lives in England. It weighs nearly one ton, or more than 1800 pounds, to be exact, and measures fifty-two feet across. The machine is balanced somewhat after the manner of the Curtiss-Herring model, by two horizontal planes placed at the extremities of the main planes and midway between the rear corners. The two main planes are seven feet six inches wide and are placed nine feet apart, which is considerably farther than in any other successful model. The upper plane is slightly curved toward the ends. The machine carries two large horizontal planes for vertical steering, sixteen feet before the entering edge of the main wings. These planes, placed side by side, have a combined area of 150 square feet and naturally exert a considerable lifting force. A small vertical rudder for horizontal steering is carried above and between these front planes. An unusually large rudder is placed well behind the machine, consisting of a vertical plane with an area of forty square feet. All the rudders are operated by a wheel in front of the pilot’s seat.

In the Cody aëroplane the horizontal rudders are moved by pushing or pulling the wheel, while by moving it sideways the two balancing planes, which control the equilibrium, are moved up and down. The most original feature of the Cody machine is the position of the propellers. They are carried in the space between the two main planes forward of the center. It would seem that they must draw the air from the upper planes and affect their lifting quality. The machine is mounted on three wheels, two beneath the front edge of the main plane, and the other slightly forward, which is an unusual distribution. The Cody biplane, with 770 feet of wing surface, lifts more than 1800 pounds.

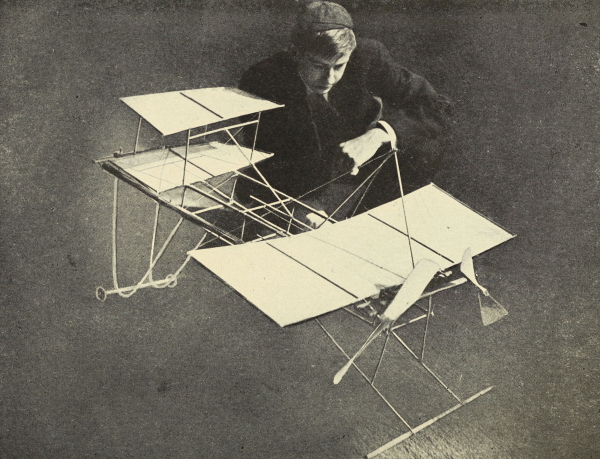

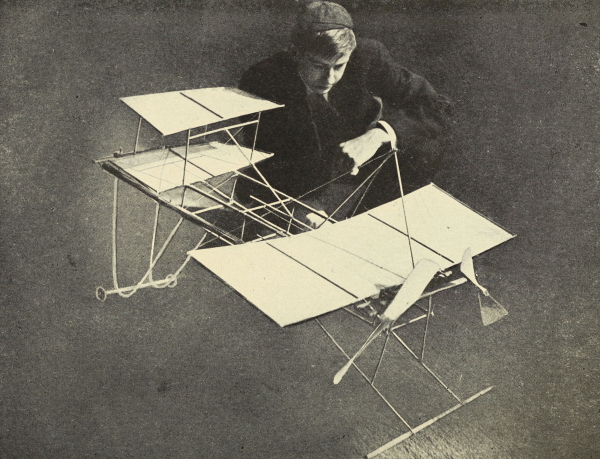

PLATE XXVI.

An Ingenious Model which Rises Quickly.

It is all a matter of guess work, of course, whether the monoplane, biplane, or some entirely new form of aëroplane will come into general use. Every model has its enthusiastic friends. The biplane, at present, has greater stability than the monoplane, and carries greater weights for longer distances. The development of the flying machine is so rapid however that in five or ten years the successful aëroplane models of to-day may appear as crude as do the clumsy, lumbering old horseless carriages of five or ten years ago.