CHAPTER VIII

SPORTS OF THE AIR, AEROPLANES

ANY contest of air-ships makes excellent sport. A city to city flight by aëroplane, for instance, attracts greater crowds than could any procession or royal progress in the past. The aëronautical tournaments and meets already have been held from Egypt in the East, to California in the west. Let an aëroplane soar higher than any has risen before, stay aloft longer, or make a new record for speed or distance, and the news is instantly cabled around the world.

All who have gone aloft tell us that flying is the greatest sport in the world. The free, rapid glide we all enjoy in skating or coasting becomes speedier and smoother in an air-ship, without exerting the least effort. It is this sense of rapid motion which has made the automobile so popular, and the air-ship improves upon the automobile, just as the automobile improved on the lumbering coaches of the past. Once aloft, the aërial passenger glides with the swallow’s swiftness. “Now,” cried an enthusiastic Frenchwoman, after her first aëroplane flight, “now I understand why the birds sing.”

As the aëroplane is brought under better control, we will see these contests grow more and more exciting. The development of the new craft has been so rapid, we have come to expect so much from it, that the exhibition at which the world marvels to-day, becomes the commonplace of to-morrow.

The early flights of the Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk failed to attract much attention. There had been so many announcements of successful flying machines that many were sceptical, especially in Europe, and the world did not realize that the great day, so long promised, was dawning. It was not till the Wrights flew in North Carolina that the world began to take the matter seriously.

Every movement of the curious new craft was closely watched thereafter. When one of the brothers went aloft the world knew it, and crowds stood patiently before bulletin boards in New York, London, or Sidney, to count the minutes. When he succeeded in staying aloft for an hour, the waiting crowds in many widely separated cities, broke into simultaneous cheers. Next came the trip to Pau, in France, and other European cities, and day by day the flights became longer and higher. The brothers made double progress, for while one was in Southern Europe increasing the time aloft, the other was flying higher and higher in Germany. In these early days no attempt was made to fly across the country. The aëroplane merely flew around and around some large field, and the distance traversed was calculated more or less accurately.

After the triumphant return of the Wrights to America, a cross-country run was made at Fort Myer, to show the Government that the aëroplane was more than a toy. A flight of twenty miles was made over a rough, mountainous country and several deep valleys. The air of the valleys drew the machine down with a dangerous rush, but the aviator pluckily worked his way higher, and passed over it in safety.

Shortly after this, during the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York, Mr. Wilbur Wright rose from Governor’s Island in New York harbor, encircled the Statue of Liberty, and again sailed high above the river north to Grant’s Tomb, and returned to the starting point. Each of these feats was, in a peculiar sense, record breaking.

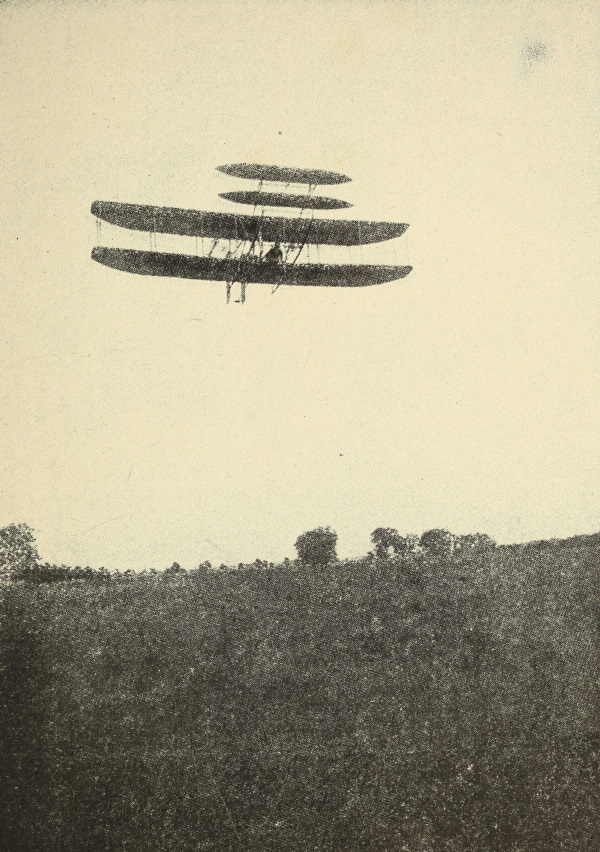

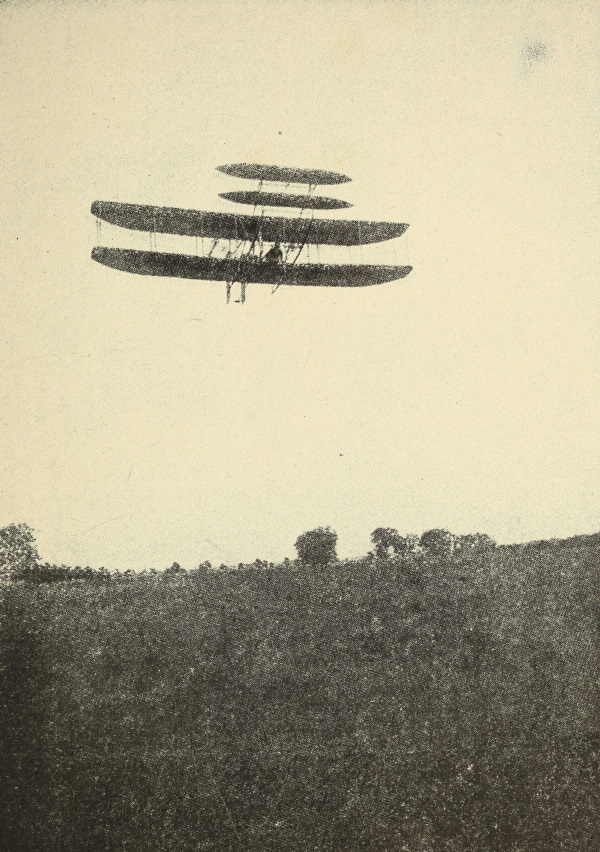

Front View of the Flight of the Wright Aëroplane, October 4, 1905.

Meanwhile, a flock of aviators were making ascensions in biplanes and monoplanes of many designs in France. Their first attempts to fly were made, as a rule, in a great field on the outskirts of Paris, where immense crowds gathered to watch them. As the aviators gained confidence in their craft, the flights rapidly became longer and higher, and short cross-country flights were made. These cross-country and over-water flights quickly out-distanced those made in America, and this lead once gained, was kept up. There are several reasons why France, after America pointed the way, should have overtaken, and, in some respects, out-distanced her. There have been more aviators in France. The prizes offered for flights of various kinds, have been ten times more numerous and valuable in France than in any other country, and this naturally invited competition. The example of France in offering valuable prizes for long flights has since been followed in the United States.

It should be borne in mind, again, that the level stretches of country common in Europe, offers fewer difficulties for the pilot of the aëroplane than the rough, mountainous, or even hilly country often encountered in America. It is possible to fly hundreds of miles in the south of France or in Italy and pass over country like a great parade ground. When a long-distance flight is made in America, rivalling or surpassing those made abroad, it is probable that it has required far more skill and daring than similar European flights. The French, again, excel in building light, serviceable motors, suitable for aëroplanes, and no small part of the success of the French air craft is due to this skill.

The cross-country trips were quickly extended. After several successful short flights, Henry Farman surpassed all records by traveling for eighty-three miles across country in France. The great feat was now to cross the English Channel. A prize of $5,000 was offered by a London newspaper for the first channel flight. Two attempts were made by a young Frenchman, Hubert Latham, but both times, after sailing out for several miles over the sea, some accident befell his machine, and he was thrown into the water. Undaunted by these failures, another Frenchman, Louis Bleriot, started early one Sunday morning, June 25, 1909, from a point near Calais, France, and landed safely at Dover on the English side. Shortly after this, still another Frenchman, De Lesseps, flew from the French coast to England in safety.

The richest of the aviation prizes, a purse of $50,000, had meanwhile been offered for a successful trip by a heavier-than-air machine from London to Manchester, a distance of 171 miles. Several attempts had been made to cover this distance, but without success. It was finally won, however, under very dramatic circumstances. Two aviators, an Englishman named White and a Frenchman named Paulhan, actually raced for the goal. The French machine got away first, but was followed by the English machine close on his heels—or should we say propellers? The greater part of the race took place at night in a high wind, and, in the upper air lanes, intensely cold weather.

Paulhan succeeded in flying 117 miles without coming down, rushing along through the night at top speed, with the dread that every sound behind him came from the machine of his rival. When he was forced to land for fuel, he worked with feverish haste, fearing that every second’s delay might cost him the coveted prize. Several times the crowd about him, deceived by some night bird, cried “Here comes White!” As a matter of fact, White was but a few miles behind. The fuel tank filled, Paulhan drove his machine full speed into the sky, and did not land till he had completed the journey and won the prize.

There was naturally a great demand for a similar journey in America, and the aviator and the prize were soon found. For several years there had been a standing prize of $10,000 for the first successful flight between New York and Albany, over the Hudson River, the course taken by Robert Fulton in his famous trip by steamboat in 1809. An effort was made to cover the distance by dirigible balloon without success. An attempt was made by aëroplane on May, 1910, by Glenn H. Curtiss, the winner of the grand prize for speed in the aviation meeting at Rheims. Curtis started from Albany, in order to face the air currents which drew up the river. After waiting for several days for fair weather, he finally got away early one morning, and, following the course of the Hudson River, made the flight to Poughkeepsie, seventy-five miles south, without mishap, when he landed for fuel.

Again rising into the air, he started south, traveling with such speed, that he outdistanced the special train which was following him. A difficult problem in aviation was met in passing over the Highlands, a rugged mountainous section, through which the river cuts a deep, tortuous channel. Curtiss rose to a height of more than 1000 feet, but the treacherous air currents drew him down and tossed him about at perilous angles. He fought his way, foot by foot, finally bringing his craft to an even keel. On reaching New York, he landed in the upper section of the city for gasolene, and once more rising above the Hudson River, flew swiftly to the riotous clamor of every whistle in the great harbor beneath him, to a safe landing at Governor’s Island.

The first great city to city and return aëroplane trip was made a few days later, between New York and Philadelphia. A new aspirant for these honors was Mr. Charles K. Hamilton, who had amazed everyone with his daring driving. He was engaged to fly over the course for $10,000, offered by a New York and a Philadelphia newspaper. He carried with him letters from the Governor of New York and the Mayor of New York City to the Governor of Pennsylvania and the Mayor of Philadelphia. He also took aloft a number of “peace bombs,” which he dropped along the route to show how accurate might be the aim of a war aëroplane. The start was made early on the morning of June 13, from Governor’s Island in New York harbor. A special train was held in readiness to follow him.

After rising to a considerable altitude, Hamilton flew in great circles about the island to try his wings, and then, signaling that all was ready, darted off to the south. He quickly picked up his special train, and, at a pace of almost a mile a minute, flying hundreds of feet in air, sped on to Philadelphia. It was estimated that more than 1,000,000 people had gathered along the route to cheer him. Hamilton had laid out a regular time-table before starting, and so perfect was his control of the machine, that he passed town after town on time to the minute like a railroad train.

The run to Philadelphia eighty miles away, was made without alighting and without mishap of any kind. Hamilton flew over the open field selected for landing, circled it three times to show that he was not tired in the least, and settled down as lightly as a bird. He was received by the Governor of Pennsylvania and the Deputy Mayor of Philadelphia, to whom he delivered his messages and received similar letters in reply to bring back to New York.

After a brief rest of little more than one hour, Hamilton was once more in the sky, flying across-country at express speed. He set such a pace, that his special train was left far behind, and it was only by running at the rate of seventy-five miles an hour, that it finally overtook him. Hamilton drew far ahead of the train on the return trip which was made in much faster time. The wind was favorable, and Newark, eighty miles, was reached at the rate of fifty miles an hour.

With the goal practically in sight, Hamilton’s engine began working badly. He pushed on, until he found himself in absolute danger, when he decided to descend. From such high altitudes, the appearance of the ground is very deceptive. Hamilton chose what appeared to be a smooth piece of green grass and dropped to it, only to discover that he had settled in a marsh. The fault in the engine was quickly remedied, but now the ground proved too soft for him to rise. In trying to rise he broke his propeller, and another delay followed, while a new propeller was hurried from New York. He finally succeeded, however, in rising and completing his trip to Governor’s Island, thus making the round trip in a day and winning the prize.

So rapid is the advance in the new science, that each aviation meet sets a new and more difficult standard. At first, people marvelled to see an aëroplane rising but a few feet from the ground, but such feats soon became commonplace. Within a few months, prizes were offered for the machine staying aloft for the longest time. The element of speed was next considered, and the aëroplanes sailed around a race course against time. The highest altitude now became a popular test feat. The pilots soon found themselves in such complete control of their machines that they gave exhibitions of landing by the force of gravity alone. The aëroplane would work its way upward in great spirals, and then, shutting off all power, coast down at terrifying angles on the unsubstantial air. It is from such tests as these that there will gradually evolve the airships of the future, the terrible engines of war, the air liners for commerce, and the light and speedy pleasure craft.