CHAPTER VII

AERIAL WARFARE

THE boys who turn these pages may some day read of aërial battles fought high above the earth, and some may even take part in them. Air-ships are even now included in the navies of nineteen nations. There is great difference of opinion among experts whether the balloon or aëroplane will prove the better fighting machine, but, meanwhile, aëronautical corps and regiments are being recruited, formidable navies of air-ships are being laid down, and special guns are being built to battle against them.

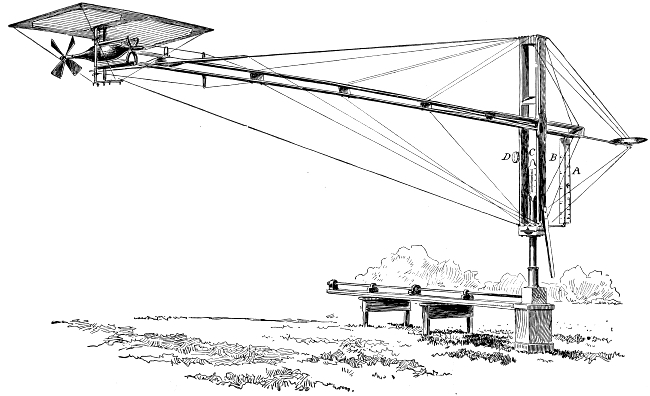

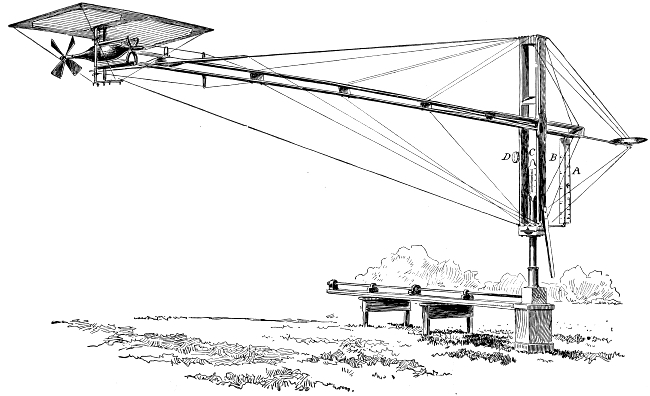

A Machine for Testing the Lifting Power of Aëroplanes.

In this machine power is transmitted from the horizontal main shaft and upward through the vertical steel spindle and through the two members of the long arm. A is a scale showing miles per hour and B a scale divided into feet per minute; C, Dynamometer for recording the push of screw; D, Dynamometer showing the lift of the aeroplane.

The ordinary balloon has played a much more important part in actual warfare than most people realize. A balloon corps was organized in France as early as 1794, when balloons were built for each of the Republican armies. One of these balloons, measuring thirty feet in diameter, was sent up near Mayence, to gain a view of the Austrian army. The balloon was held captive by two ropes, and an officer in the car wrote his observations, weighted the letters, and dropped them overboard. The Austrians were furious at this spying, and opened fire, but the ropes were lengthened and the balloon rose to a height of 1300 feet, where it was out of range. Several years later balloons were again used in battles by the French against the Austrians, who were so angry with the new machine that they declared that any balloonist captured would be shot. For a long time afterward, however, this method of warfare was neglected, and even Napoleon could not see its value, and closed the aëronautical school and disbanded the corps.

The use of the balloon was revived in America during the Civil War, and proved to be so valuable that no great war has since been fought without it. During the attack on Richmond, a number of balloons were sent up daily by the Federal Army to overlook the besieged city. From a point eight miles away, valuable information was gained as to the position of the troops and the earthworks. A telegraph apparatus was taken up and messages were sent directly from the clouds, almost over Richmond to Washington.

In the Spanish-American War in 1898, the balloon was again called into use. One ascent was made before Santiago, Cuba, and the position of the various Spanish forces were observed and reported. Another was sent up at El Paso, less than 2000 feet from the Spanish trenches, and the position of the Spanish troops on San Juan Hill was discovered. The balloon was finally brought down by the Spanish guns.

During the siege of Paris in 1870, balloons were used successfully to escape from the city. Some sixty-six of them, carrying 168 passengers, succeeded in passing over the German armies. The French army has also made good use of the balloon in the wars in Madagascar, and several English balloon corps were engaged with the British army during the Boer War.

For ordinary military work, balloons of three sizes are used, a large balloon for forts, the regular war balloon, and an auxiliary for field work. The large balloon holds 34,500 cubic feet of gas and is only used above fortifications. The regular field balloon is thirty-three feet in diameter, and holds 19,000 cubic feet of gas. It is designed to carry two passengers to a height of 1650 feet. The auxiliary balloon is considerably smaller, holding only 9200 cubic feet of gas, and carrying but one passenger. It is much easier to handle on long marches, and, of course, may be filled and sent aloft in much less time.

The balloons are usually filled from cylinders, which may be hurried across country in carts or automobiles. There is, besides, a regular field gas generator, readily packed up and carried about, which will fill an ordinary balloon in from fifteen to twenty minutes. To resist aërial attacks, a special armored automobile has been adopted by some European armies, carrying a gun which may be aimed upward and at any angle. Despite its weight, the automobile will travel at the rate of forty miles an hour. The recent developments of the dirigible war balloon has rendered the free balloon practically obsolete, and it is unlikely that it will ever again be used in actual warfare.

The United States has been the first country to adopt the aëroplane as a weapon of warfare. After the successful flights of the Wright Brothers, the War Department purchased one of their aëroplanes, and several officers were instructed in driving it. Before being accepted, the Wrights were required to make a flight of ten miles over a rough, mountainous country near Washington, and return without alighting. The test, which was highly successful, was witnessed by President Taft and many representatives of the Government. In the event of war, the United States Government could quickly mobilize a formidable fleet of aëroplanes, and man them with experienced aviators.

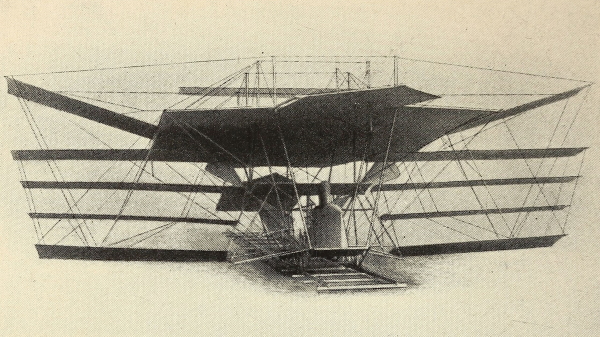

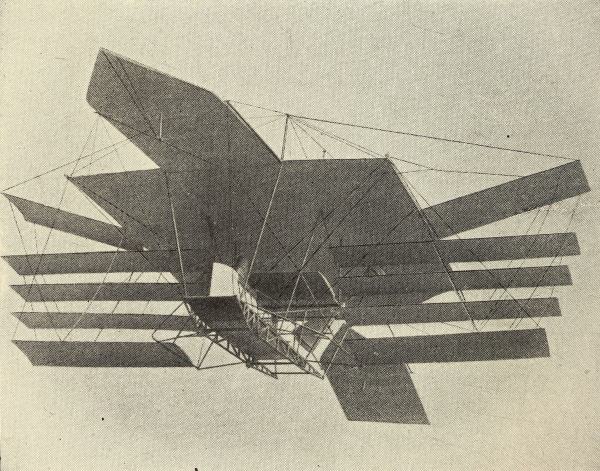

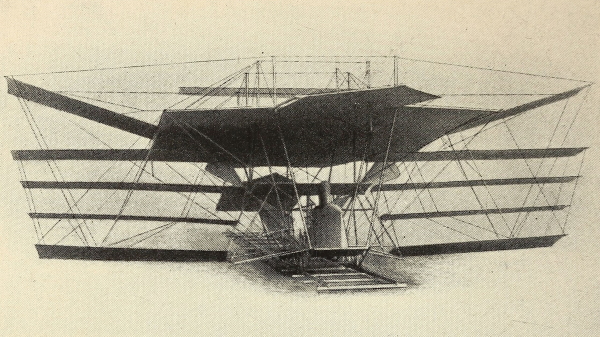

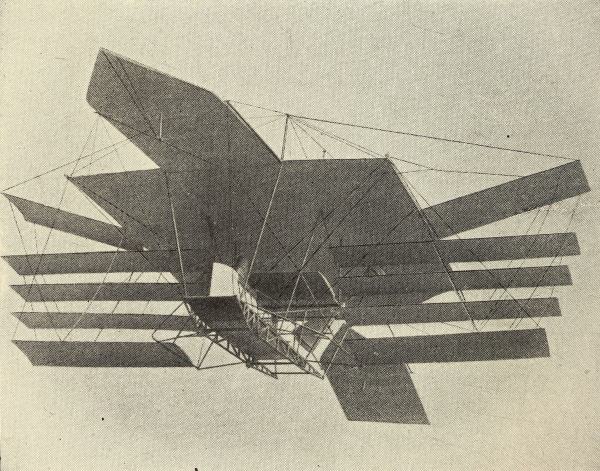

The Machine on the Rails, as it appeared in 1893.

Maxim’s First Aëroplane.

The value of aëroplanes in warfare has been widely discussed by military experts. There was, at first, a general impression that such flights were much too uncertain to be of practical value. The marvellous development of the aëroplane, and its remarkable flights over land and sea, have served to silence much of this criticism.

Although an over-sea invasion by a fleet of air-ships would seem to be a danger of the very distant future, the United States Government is already preparing to meet the situation. A remarkable series of tests have been made at the Government Proving Grounds at Sandy Hook, by firing at free balloons as they sailed past the fort. The balloons were sent away at various altitudes, in some cases at a considerable distance from the guns, and again directly above them. The difficulty in hitting such targets was found to be very great. The air craft moves so quickly that it is almost impossible to bring a gun of the ordinary mounting into position. Although the results of the test were closely guarded, it is known that the Government was not satisfied with the defense of New York Harbor, in the event of an aërial invasion, and special guns are being designed to repel such an attack.

The military authorities look very far into the future in their preparations. One of the most interesting of these problems is that of protecting our seacoast, should a fleet of aërial warships be sent against us. One of the plans suggested is to raise a series of captive balloons at regular intervals along the shore. It has been thought that some of these might be held near the earth, while others are allowed to ascend to a great altitude. The lookout in these signal stations could sight the approach of an hostile fleet of air-ships at a great distance, and by means of wireless apparatus warn the country of approaching danger.

Many military experts, who have watched the flights of aëroplanes, have decided that the little craft would also prove an extremely difficult object for the enemy to bring down. Since they travel at upwards of a mile a minute, ordinary guns, as they are now mounted, could not hope to hit them except by a lucky shot. It would be like hunting wild geese with a cannon. At a height of several thousand feet, which they can readily attain, an aëroplane might defy the most formidable batteries in the world. Should a fleet of these little craft be sent against an enemy, many of them would be sure to survive an attack, even if a few should be lost. It does not seem probable that the aëroplane will carry aloft a cannon large enough to do any damage. But they can drop high explosives, with astonishing accuracy, and would do important scout work.

At the present cost of construction, a fleet of one hundred aëroplanes might be built and put in commission in the field or sky, for what a single great battleship would cost. It has been shown, moreover, that a man can learn to operate an aëroplane in less time than it takes to learn to ride a bicycle. The Wrights instructed Lieutenant Lahm to drive one of their machines in about two hours of actual flight. The war aëroplanes would call for great bravery and daring, but who can doubt that men would be found to serve their country, if need be, by facing this appalling danger.

In military language, the modern airships fall into three classes, dreadnaughts, cruisers and scouts. The dreadnaughts of the air are the largest dirigible balloons, such as Zeppelin flies. They will probably be used in aërial warfare in the first line of battle, and for over-sea work. The cruisers comprise the dirigibles, such as have been brought to great perfection in France. These faster air-ships will rise higher than the dreadnaughts, and will probably be used for guarding and scout work. The aëroplanes come under the head of scouts, and will be used for dispatch work, and for attacking dirigibles.

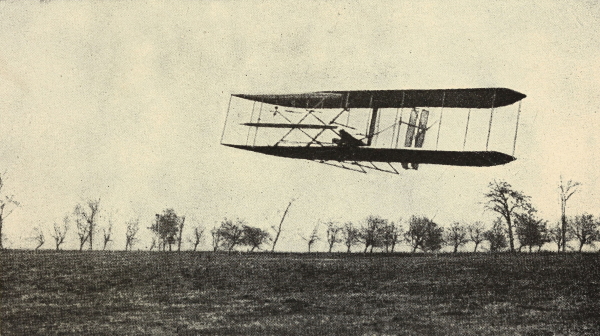

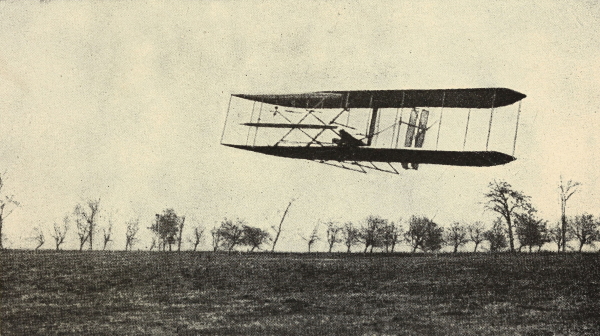

First Flight of the Wright Brothers’ First Motor Machine.

This picture shows the machine just after lifting from the track, flying

against a wind of twenty-four miles an hour.

Their speed and effective radius of travel place the air-ship in the first rank among the engines of war. The value of the free or captive balloon has, of course, been clearly proven. It has been of the greatest value for general observation work in the field. It has been readily raised out of effective range of the enemy’s batteries, and from this position, has looked down upon the forts, cities, or encampments. It thus became a signal station which might direct gun fire with absolute accuracy, and has been the only safe and reliable method for locating the presence of mines and submarines.

The dirigible balloon possesses all of the qualities of the free balloon and many more. It can attack by day or night. Its search lights enable it to look down upon the enemy with pitiless accuracy. It may thus gain information about forts and harbors, which otherwise could not be approached. The most completely mined harbor in the world has no terrors for such a visitor. The great problem in warfare of patrolling the frontier of a country against possible invasion seems to be solved by the dirigible. Two or three men aboard a dirigible, with a traveling radius of several hundred miles, could do more effective work than several thousand men scattered along the frontier line.

For dispatch work the flying machine is expected to be indispensable in warfare. The bearer of dispatches has always played an important part in war. His work is often of the most perilous nature, and his journeys, at best, are slow and uncertain. The dispatch bearer, driving an air-ship fifty miles an hour, could ride high above the range of the enemy’s guns. These same vehicles of the air would doubtless be equipped with wireless telegraph apparatus, so that they might send or receive messages, and the aviator might talk freely with the entire country side, directing a battery here, silencing one there, ordering an advance or conducting a retreat, with unprecedented accuracy.

These aërial fleets may also carry on deadly aggressive warfare. The over sea raid will have greater terror than any ordinary invasion. A fleet of dreadnaughts dirigibles, assisted by fast cruisers of the air, and many aëroplane scouts, would be extremely formidable. An enemy’s base line would be at the mercy of such an invasion. Within a few hours, such a fleet might destroy the enemy’s stores, its railroads, and its cities, by dropping explosives or poisonous bombs.

In several recent aëroplane flights, “peace bombs” have been aimed to strike a given mark, and the shots have proven surprisingly accurate. By using various instruments to determine directions, it will be possible to drop such bombs with mathematical accuracy. The bombs or missiles will be suspended by wires from beneath the air-ship and released by an electric current, to give them a perfectly vertical direction. When dropped from great altitudes, the effect of such explosions will be difficult to withstand. Our great war-ships, despite their steel sides, will probably have to be completely remodelled before they can fight with this new enemy.

When an air-ship drops a bomb from a point directly above a fort or ship, it will be absolutely out of the range of the enemy, since to shoot directly up into the air would be to fire a boomerang which would quickly return and inflict serious damage. An actual test was recently carried out in England, when a thirteen pound gun fired at a balloon 1000 feet in the air. Although the gun had an effective range of 4000 feet, and the balloon was held captive, it was not until the seventeenth shot had been fired that it was brought down. It has also been proven that a rifle ball will be deflected by the draught from the propeller of an aëroplane. The flying machine promises to revolutionize warfare.

Three-quarters View of a Flight at Simms Station, November 16, 1904.