CHAPTER V

VILLA GARDENS TO THE EAST OF FUNCHAL (continued)

THE Quinta do Til is one of the oldest villas in Funchal, and a description of it is to be found in “Rambles in Madeira and Portugal,” published anonymously in the early part of 1826, in which the writer says: “The Til is a villa in the Italian style, and possesses much more architectural pretensions than any I have seen here; but it has never been finished, and what has, bears evident symptoms of neglect. The name comes from a remarkably fine til, one of the indigenous forest trees of the island, which stands in the garden, ingens arbos faciemque simillima lauro: it is, I believe, of the laurel tribe. In the court, too, is an enormous old chestnut, the second largest in the island.”

QUINTA DO TIL

The effect of the garden never having been finished is due to the fact that the balustrade of the lower terrace still remains carried out in wood instead of stone, or at least cement and plaster, as was no doubt intended originally. Possibly the death of the original owner caused the property to change hands, and fall into the possession of one who had no sympathy with costly garden architecture. The garden has lost much of its Italian characteristics, as, though not mentioned in the above description, the lower garden was formerly planted entirely with orange-trees, and four large cypresses stood like sentinels near the fountain. Disease killed the orange-trees, as, indeed, it has killed almost all the orange-trees in the island, and the cypresses are also gone, so the garden is now entirely a flower-garden. On the upper terrace the trunk still remains of the chestnut-tree mentioned in the above description; it must have been of gigantic proportions, as the trunk measures many yards in girth. It now supports a single Banksia rose-tree, which is wreathed with its little white starry blossoms in early spring. The chestnut-tree has been replaced by a Magnolia grandiflora, which has grown into an immense tree, and is now probably one of the largest in the island. In June, when its large leathery white blossoms expand, it fills the air, especially near sundown, with its almost overpowering fragrance.

The upper terrace is laid out with beds, surrounded by box hedges a foot or more in height, which are filled with an infinite variety of well-grown plants. The garden is very sheltered, and never seems to suffer from the strong, rough winds which those in a more exposed and open situation feel so keenly. Here there comes no rude blast from the east to strip the leaves off the great begonia plants, and their brittle foliage and heavy flower-heads remain unbruised and untorn, while many a neighbouring garden has suffered severely at the hands of a winter storm. Each plant is a perfect specimen in itself, and is the result of many years’ care and attention. New-comers to the island are apt to think that in this glorious climate plants are very quickly established, that cuttings will make large plants in at most a few weeks, seeds will spring up in a night—in fact, that gardening is so easy that it is small wonder that gardens filled with plants such as we find here are to be found. Personal experience has taught me that as a rule plants are rather slow to establish, cuttings strike slowly and take a long time to make their roots, especially in the winter months, and the same applies to seeds unless they are sown in early autumn. Once established—say the second year—plants, especially creepers, will make astonishingly rapid growth, but patience is required at first, though well rewarded in the end.

It is evident that this garden is tended with loving hands, and all the necessary alterations and pruning are done under the close supervision of its owners. Their collection of begonias is a large one, and they seem to thrive better in this garden than anywhere else in Funchal, and appear to be in perpetual flower. Pelargoniums of the varieties known in England as Show Pelargoniums, and not of late years much cultivated, new favourites having ousted them from the greenhouse, are here grown into large bushes, many of them five and six feet in height. It is only growing freely in this way that one has any idea of the beauty of many plants which we only know cramped in the narrow area of a six-inch pot. In Southern Italy I remember these same varieties of pelargoniums were grown hanging over terrace walls, and possibly were even more beautiful than when receiving artificial support.

It would again be impossible to enumerate all the plants in this little garden, but it brings to my mind’s eye a vision of fuchsias, bouvardias, a beautiful deep mauve lantana, the clear yellow Linum trigynum, and hosts of sweet-scented plants, such as verbenas, sweet olives, sweet-scented geraniums, diosmas, and many others.

The lower terrace is almost entirely a rose-garden, the Til garden having always been famous for its roses.

If a few plants of a new rose are imported, the stock can be easily and quickly increased, as the budding of roses, or even grafting, seems an easy matter in this country. The buds take quickly, and the stock may be either that of Rosa Benghalensis, which has become naturalized in the island, or any rose which has been proved to have a good constitution may be utilized as a parent. As I have remarked elsewhere, the branch which has been budded is as often as not layered in its turn, and in a few weeks will have rooted, and can be detached from the parent plant; there seems no reason that, once a new variety has been proved to have taken kindly to the climate and soil, a good stock should not be procured and a large group of the same kind planted together, whereby a much better effect is always obtained.

A creeper-clad corridor leads to the group of trees which have given their name to the quinta.

Just above, on the Levada da Santa Luzia, is the gate of the Quinta Palmiera, which takes its name from the large palm-tree which rears its head proudly and stands alone in the grounds. The path leading to the house winds up the side of the hill, through grounds which for many years had been out of cultivation, until the property changed hands a short time ago; but as the ground had always been left in more or less its wild and natural state, it suffered less than if it had been a cultivated garden.

It is a beautiful piece of rocky ground, and on one side a group of Pinus pinea, stone, or parasol pines, stand towering over a grand cliff which rises abruptly from the river-bed. In November the rocks are covered with the red spikes of the blossoms of the Aloe arborescens, and the effect with the great pines and cypresses beyond is one of indescribable beauty. This is the only villa which can boast of the possession of fine cypresses, and here one realizes the ornament they would be to the island if they were more lavishly planted. The ground near the house is admirably suited for broad terracing, and a splendid effect could be obtained by leaving the cypresses standing out against the distant sea. But the rock being so very near the surface, and the absence of soil, combined with the lack of any means of carting, would make terracing a very serious undertaking.

The grounds contain many very fine trees—among others, a very good specimen of the deciduous cypress, Taxodium distichum, which is also called the swamp, or Mississippi cypress, as the whole valley of the Mississippi is clothed with these trees. In summer they are of a splendid deep emerald-green, which gradually turns to a bronze-red colour in autumn, and by December the trees are bare.

At the back of the house there is one of the largest coral-trees in Funchal, and a very large til-tree stands immediately in front of the house.

Among other villas with good gardens, the Deanery, which has long been noted for its fine collection of trees, and the Achada, cannot be omitted. The Deanery, standing in a very sheltered situation at the foot of the Santa Luzia ravine, has proved an admirable trial-ground for trees, shrubs, and plants which have been collected by its present owner. From all parts of the world rare and interesting plants have been brought, and some have been raised from seed on the spot. The following description of the place was written in the early part of the year 1826 by a traveller in Madeira and Portugal, and shows that even in its early days the garden was well cared for:

“To-day we have removed to Deanery, our country-house. The house is a very pretty one. It has not long been built, and, in fact, only a portion of the apartments has as yet been used for residence, but there are more than enough for our accommodation. The situation is delightful—scarcely a quarter of an hour’s walk from Funchal, and enjoying, from its comparative elevation, a beautiful view down the valley to the city (which, though so near, is scarcely visible from the orange-trees and cypresses that embower us), and to the bay and coast and the blue Desertas beyond. Close on the west is the Santa Luzia ravine, the farther side of which rises to a considerable height, its cliffs terraced, in the way I previously described, into little gardens and vine-grounds, and crowned by the trees and trellises of the Achada Quinta.

“Our great luxury, however, is the garden. It is one of the largest and most beautiful in the island. A spacious vine corridor runs round nearly its whole extent, under the green arches of which in summer, you may either ride or walk in coolness, while the interior space forms a ‘leafy labyrinth,’ in which trees and shrubs, flowers and fruits of every clime are here crowded into a wilderness of shade and beauty. The higher part of the ground, upon which stands the house, is elevated considerably above the rest, and is divided from it by a terrace of considerable height. This circumstance is of very happy effect for the beauty of the garden: it in a manner doubles its extent, and multiplies its variety; while the wall of the terrace, in some parts nearly twenty feet high, affords an admirable field for every species of tropical creeper, to luxuriate, as it were, at full length, and to put forth its leaves and blossoms to the sun, in all the fearlessness which such a climate and aspect justify.

“Above the house the ground rises another step, and the boundary of the garden here is a wall of native rock, which is already half veiled with the trees and trailing plants interposed to relieve its ruggedness. The freshness of the scene is completed by the tanks, always copiously supplied with running water, and which a little trouble might, I think, bring into play as fountains.”

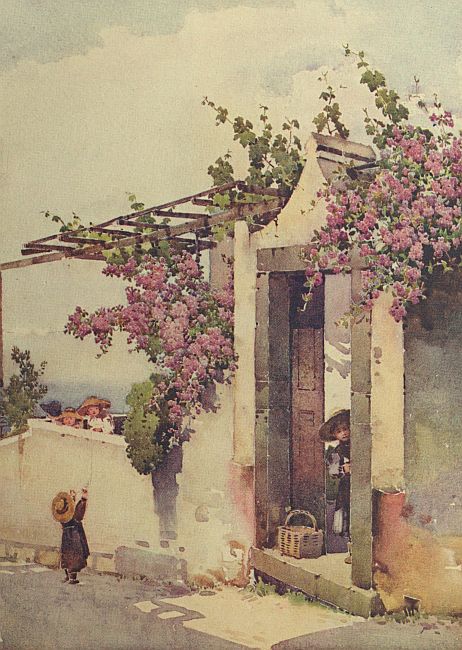

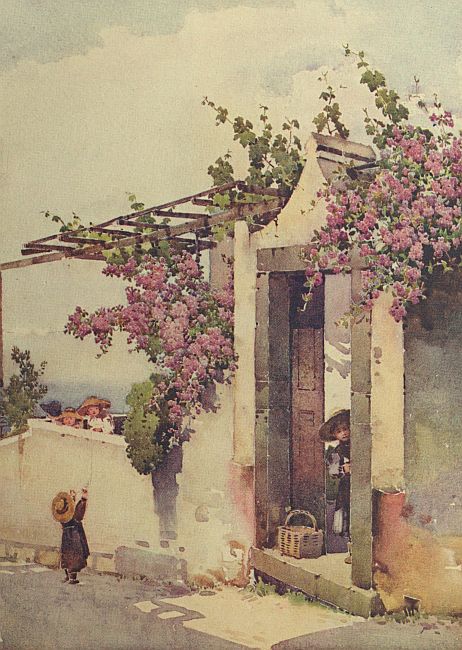

Across the ravine, but at a very much higher altitude, stands the Achada, in a commanding position on, as its name implies, a stretch of level ground. The road leading to it from the town, known as the Caminho da Sao Roque, as it eventually leads to the village of that name, is almost as steep as the Mount Road, and a very pretty view of the town is visible between its creeper-clad walls, with the picturesque church and tower of Santa Clara in the distance. The Achada has also long been famous for its garden and grounds. It formerly belonged to an English family, who probably planted most of the rare trees, palms, and Dracænas, and the large magnolia-trees for which it has become famous. The property then changed hands, and for some years belonged to a Portuguese family, but is now again in English hands. The following is by the same unknown author of the above description of the Deanery in 1826: “The English merchants all have mansions in the city, but they commonly live with their families in the country-houses in the neighbourhood of it. To-day we have been returning visits, which has taken us to some of the finest of these quintas. One of them is the Achada. The situation is delightful: it stands on a level, the only one in the environs, just above the city, and thus enjoys an advantage in respect to surface possessed by no other. The grounds are extensive, rich in fruits and in flowers, and surrounded by alleys of vine trellises. These vine corridors, as they are called, are common to all the gardens, and in summer, when the plant is in leaf, must be peculiarly grateful.”

ON THE TORRINHAS ROAD