CHAPTER IV

VILLA GARDENS TO THE EAST OF FUNCHAL

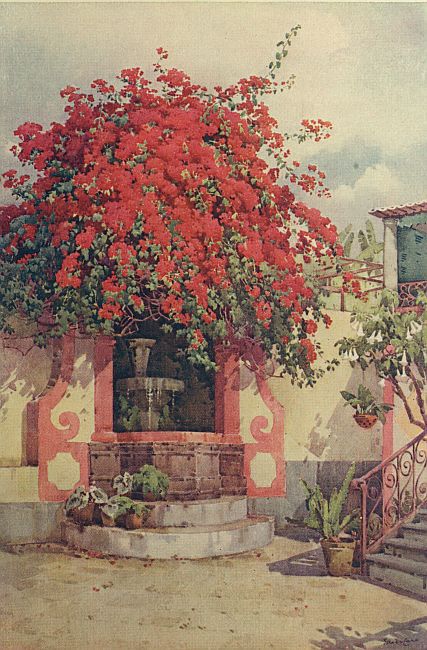

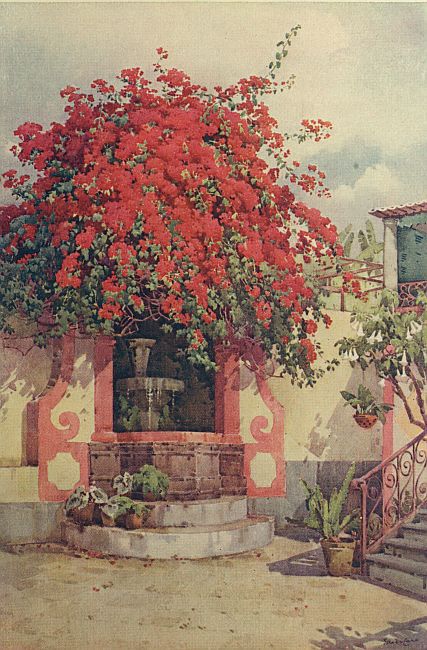

ON the east side of the town lie many quintas with good gardens, especially up the very steep Caminho do Monte, or Mount Road, as it is commonly called by the English. The road itself at some seasons of the year is converted into a veritable garden, as its high wall is so clothed with overhanging creepers which have strayed from the gardens behind, that it presents more the aspect of the terrace wall of a flower garden than that of one of the most frequented highroads of a town. At a height of between 500 and 600 feet, just below the level road which crosses it, which is known as the Levada da Santa Luzia, several villas seem to vie with each other as to which can contribute the greatest wealth of plants to decorate the walls. Possibly the best moment to see the road is in December, when the gorgeous mass of colour provided by the great shrubs of poinsettias hanging over the walls of the Quinta Santa Luzia is in all its splendour. Side by side with the scarlet blossoms come the great white trumpets of the daturas, hanging in horizontal rows. Below, the deep rose-coloured buds of the bougainvillea have not yet unfurled, so there is no jarring note in the scheme of colour, as the immense bank of plumbago, with its soft blue blossoms, harmonizes admirably. On the other side of the road, as if determined to continue the effect of the flaming red, is a great cluster of Aloe arborescens, with their spikes of red flowers—not, it is true, as brilliant in colouring as their opposite neighbours, the poinsettias, but very beautiful in themselves. These, with clumps of sweet-scented geraniums, echiums, and many other plants, clothe the walls of the garden of the Quinta da Levada. But the stream of gorgeous colour is not yet complete, as the Bougainvillea spectabile, with its brick-red blossoms, is already giving promise of glories to come in a very short time. This plant, which covers the corridor and hangs over an old garden well at Quinta Sant Andrea, is the finest specimen of its kind in the island. From the immense size of its stem, it is easily seen that the plant must be a great age, and for many years has borne its burden of blossoms and called forth the admiration of untold numbers of tourists through successive winters, as they make their noisy descent in the basket sledges or running cars from the mount.

THE SCARLET BOUGAINVILLEA

In a few weeks the road is turned into a golden road. The poinsettias and aloes will have shed their blossoms, and are soon forgotten, as the brilliant orange bignonia clothes many a wall and corridor, and in its turn attracts all attention. By April the wistaria takes its place, and the road becomes all mauve, as nowhere in the whole of Funchal are there so many beautiful wistarias collected together; all along this road they seem to have been planted with a lavish hand. Possibly the soil is especially suited to them in this district, as I have often heard owners of gardens in other parts of Funchal regret that they have never been able to establish this most beautiful of all creepers in their gardens.

It is small wonder that the sight of these flower-clad walls fills many a visitor to the island with a longing to see the gardens they enclose.

The palm must be given to the garden of Santa Luzia, as not only does it cover a much larger expanse of ground than any other, but the owner takes so much individual interest in almost every plant in the garden, that here, as it is always said flowers grow better for those who love them, everything seems to flourish and grow at its best. Like all good gardeners, she has not been deterred by the failure of a plant one season or the failure to import a new treasure at the first attempt, but has given hosts of plants a fair trial, often rewarded with success in the end, though naturally failing in some cases. Plants have been sent to her from all parts of the world, and the island owes many of its flowery treasures to this garden, which was originally their nursery and trial-ground. One of the most remarkable instances of this is Streptosolen Jamesonii, originally introduced to this garden, but which only succeeded the fourth time it was imported, and has now spread, until there is hardly a humble cottage garden in the whole of Funchal which is not decorated with its orange bushes in the winter months. The garden has been much enlarged of late years, and gradually terrace after terrace has been added to it, many of them forming a complete little garden in themselves. From the lie of the ground in a steep slope in two directions, and possibly from the fact that the garden has been added to gradually, it shares the difficulty I have described elsewhere, and had no very imposing scheme to start with.

WISTARIA, SANTA LUZIA

The entrance to the garden leads one to expect a wealth of flowers in the garden below, as a vision of pink begonias with a profusion of blossom, tall feathery bamboos, and long hanging ferns, greets the eye at the very door. On the terrace in front of the house stands one of the finest wistarias. It clothes the whole wall, makes a purple canopy to the corridor, climbs up the square pillars, and has even taken possession of the flagstaff, so in the early days of April the whole air is filled with its delicate bean-like scent. The beauty of its blossoms is short-lived, and possibly for this reason is all the more appreciated. A few short days and the heat of the sun will have taken all the colour out of its purple tassels, the leaves will begin to appear, and all its glory is departed. Some of the winter-flowering creepers last in beauty so long—for weeks or almost months—such as the bougainvilleas and Bignonia venustus, that if such a thing were possible, one becomes almost wearied of their beauty, and passes them by almost unnoticed. But with wistaria it is different: it must be noticed and appreciated at once or not at all, as the colour changes and fades with every passing hour.

Possibly April is the best month to visit this garden, though at no season is it without flowers, but March, April, and May are the best months of the year in all Madeira gardens. In some ways the autumn here seems as though it ought to be spring. Late in September or early in October the gardens go through the tidying up, pruning, and cutting back, which is generally done in our English gardens in early spring, and are made ready to reap the full benefit of the heavy autumn rains. Here during the summer everything has been left to grow as it will: the roses put forth long, rank, flowerless growth; the creepers grow out of all bounds; geraniums grow “leggy,” with long leafless stems; the heliotrope has flowered itself to death, and must be cut back in order to make fresh growth for the coming season. The gardens by the end of the long, dry summer must present the aspect of an overgrown jungle, and according to the judicious or injudicious pruning in September and October will greatly depend the failure or success of the garden for the rest of the year. This also is the season for sowing seeds, and probably the best moment for starting newly imported treasures; it is most important that all these operations should be got through early in October, as by November it is soon evident that it is not really spring; the sap is not really rising, and through December, January, and February, it lies more or less stagnant and dormant, so unless seedlings and cuttings have made a good start before then, they will grow but little during those three months. The same will apply to plants which have been cut back; they should have made fresh shoots before the middle of November, or they will remain more or less bare and unsightly throughout the winter. By the time when most of the English owners return to their gardens in late November or early December, all traces of the necessary cutting should have vanished, and though the garden may not be gay with flowers, it should be full of promise of glories to come. But it seems hard to train a Portuguese gardener to get through his pruning at this season, and to have done with it for the time being, as, according to his ideas, pruning should be done apparently promiscuously, at any and every season of the year, and he is never happy without a pruning-knife in his hand, as often as not dealing death and destruction to a plant when it is in full beauty.

In the lower part of the garden a small pond, shaded by a weeping willow, whose parent was grown from a cutting brought from Longwood, provides a home for the white, pink, and blue water-lilies, which, with a large clump of papyrus, speedily remind one that one is in subtropical regions, where no breath of winter will ever reach the water sufficiently to bring death to the blue lilies which we in England know as pampered flowers, and can only grow by providing them with a warm bath, heated by artificial means.

On one of the terraces broad sheets of the mauve Virginian stock—with us an unconsidered little flower, but here, from the sheer wealth of its blossoms, providing a mass of colour—lead to a little Iris garden. Only the white Iris Florentina and a deep purple Iris Germanica really seem to flourish, so the beds are filled with these two kinds only. Iris Pallida and many of the other beautiful varieties of Iris Germanica have refused to make a home here, so the two kinds only have been retained, and for a few weeks in late December and early January the little garden is all purple and white. The purple weigandia flowers and the white of the Porto Santo daisy-trees help to carry out the colour scheme. The walls of the little garden are clad with the old Fortune’s yellow roses, called by some Beauty of Glazenwood, and it is certainly one of the roses which thrive best in Madeira, bearing its burden of yellow and pink-tipped blossoms in the spring. On the corridor above a host of creepers flourish, but the blossoms of the Burmese rose were new to me. Its large single blooms open a delicate lemon colour, which gradually turns to white, and its shiny foliage is also very ornamental; but I fear its constitution will never stand the cold of our English winters, or even if it survived the cold, the warmth of our summers would not be sufficient to ripen the wood enough to make it flower. I believe it to be the same rose which has been grown with some success on the Riviera under the name of Rosa grandiflora. Near by is its fellow-countryman, the Burmese honeysuckle, suggesting a monster form of French honeysuckle; the foliage of its long twining branches closely resembles it, only on a very large scale, and the white trumpets of its blossoms, instead of being one or one and a half inches long, are from four to five inches in length. The heavy scent is almost overpowering, coming at a season of the year when the air seems to bring out the scent of the flowers to such an extent that they become almost offensive.

The garden is so full of interesting trees and shrubs that it would be a hopeless and never-ending task to attempt to enumerate them all, but the curious trunk and roots of all that remains of a formerly grand specimen of a Bella Sombra, or Phytolacca dioica, attract the attention of all new-comers. From the uncouth root have sprung numerous fresh branches, but they can never make a fine tree like their original parent. As a foliage plant Monstera deliciosa, a native of Mexico, makes a fine group where it can be allowed sufficient space to throw out its long aerial roots, by which it will firmly attach itself to a wall or bank. It must have been these strange roots which gained for it the first part of its name, as its deeply perforated dark green leathery leaves are no monsters, and I imagine it owes the second part to its fruit, which I have seen described as being “succulent, with a luscious pine-apple flavour.”

There is a very fine specimen of Bombax, or silk cotton tree, which has a peculiar growth, and in June is covered with fluffy white blossoms.

ROSES, SANTA LUZIA

At again a lower level on yet another terrace is a little sunk garden, which seems to provide a never-ending wealth of colour and blossom. Between its box-edged beds run narrow walks, paved with flag-stones, a welcome relief to the usual paving with little round cobble-stones, and certainly pleasanter to walk upon, and in spring, when flowers spring up in every direction, many a little treasure appears between the stones. One I remember I could never regard as a weed, though many people seemed merely to look upon it as such, was Anamotheca cruenta, a tiny little bulb which bears very brilliant salmon-pink blossoms in clusters of five or six, each with a deep crimson mark in it. It is a native of the Cape, from where it was no doubt originally imported, and seems to sow itself freely. The borders are devoted to large clumps of such plants as eupatoriums, salvias, euphorbias, pelargoniums, albizzias, justicias, begonias, crinums, and imantophyllums, while in the centre of the garden rose-beds carpeted with freesias, and beds of the dark purple heliotrope, pink begonias, and lilac stocks, provide good masses of colour. Over the wall at one end of the garden, which is the boundary wall of the garden proper, hang great bushes of poinsettias, daturas, and large clumps of echiums, and on the top of the low wall on the other side, large pots of azaleas, diosmas, begonias, and ivy-leaf geraniums stand with very good effect.

Yet another of these little terrace gardens has been devoted entirely to the culture of blue and white flowers, which is a pretty idea, though true blue flowers are scarce. Blue salvias and solanums, justicias and linums are a good foundation for the garden, which, again, has paved walks, into whose cracks innumerable treasures have sown themselves. Freesias, violets, which, though not true blue, are too sweet to be ruthlessly weeded out, and forget-me-nots seem to flourish between the stones. Plumbago and Solanum crispum clothe the walls on one side, and the chief treasure of the blue garden, Echium fastuosum, provides a forest of great blue spikes all through March. This plant, which is a native of Madeira, and is generally called Pride of Madeira, finds a home among the cliffs on the seashore, but in a cultivated state it is a much more beautiful plant. It is raised from seed, and the plants seem to be at their best about the second year, producing innumerable large feathery spikes of bloom of a very bright blue. There seem to be different strains of it, as occasionally it is merely a dingy grey, and I have never seen it so good a colour in its wild state, nor with such large heads of bloom, so it is to be hoped that this garden variety will be perpetuated, though it is possible that it is merely the soil which affects its colour, in the same way that it affects the colour of the hydrangeas. Even the little fountain in the centre of the garden carries out the scheme of colour, as the water reflects the deep blue sky above, and the fountain itself is made with blue and white tiles, and makes one regret the good old days when tiles, with their patterns in soft harmonious colourings, were used architecturally and let into walls in panels. There are still a few to be seen in the grounds of the Santa Clara Convent, and on the tower of the church, showing that in former days Funchal had probably more architectural beauty than it has to-day.

PRIDE OF MADEIRA AND PEACH BLOSSOM

In April and May the garden seems a feast of flowers in whichever direction you turn your eyes, though there are some good stretches of mown grass to relieve the eye and give a sense of repose. The corridors are clad with roses, among which at this moment the large single white Rosa lævigata, with its shiny foliage, is one of the most beautiful. It resembles the Macartney rose, and is often mistaken for it. The plants are seldom entirely without bloom all through the winter, but it is early in April that it becomes a sheet of starry blossoms. Being only half-hardy in England, the climate of Madeira suits it admirably; in fact, I remarked that as a rule it is the roses which are tender in England which thrive best in Madeira. Among the best are the old General Lamarque, which grows rampantly and seems to take care of itself. Its great clusters of snow-white blossoms come in masses in December, and again in April and May. Safrano, Souvenir d’un Ami, Georges Nabonnand, Souvenir de la Malmaison, and Adam, are among the old favourites, though some of the newer kinds of that most beautiful class of roses—Hybrid Teas—seem to take kindly to the climate. It is useless to attempt to grow any Hybrid Perpetuals: they may bloom fairly well the first year, but never again. I have seen good blooms on many of the Hybrid Teas, such as Antoine Rivoire, Madame Abel Chatenay, and others, though never attaining to the perfection of English roses. Possibly the pruning may be at fault, and if the trees were better pruned, better flowers would be the result; but their rampant growth makes them, no doubt, difficult to deal with, and it would be a serious undertaking to cut away all the weak wood from the very large bushes, and certainly the ordinary Portuguese gardener makes no attempt to do so. As a rule, he merely clips the trees, shortening back all the growth equally in the month of January. I believe by a careful system of pruning a succession of roses might be obtained all through the winter, and if, as soon as one crop of bloom was over, the tree was carefully and judiciously cut, a fresh crop could be got in from six weeks to two months.

There are several roses which are to be found in most of the gardens to which I could never put a name: one in particular I can recall, with a beautiful clear, bright pink blossom, touched with a deeper red on the back of the petals, which I frequently admired and endeavoured to get correctly named; but no one knew its name, and at last a friend said: “Why worry about its name? We just call it ‘The most beautiful rose that grows’”—and it seemed indeed a good name for it.