CHAPTER VII

CAMACHA AND THE MOUNT

THE road past Palheiro leads, through pine woods and long stretches of yellow broom and golden gorse, to the little mountain village of Camacha. Probably the village has become noted for its flowers from the fact that many English people, in the days when travelling was not so easy, used to make this place their summer-quarters, instead of returning to England, as they mostly do in these days of quick travelling.

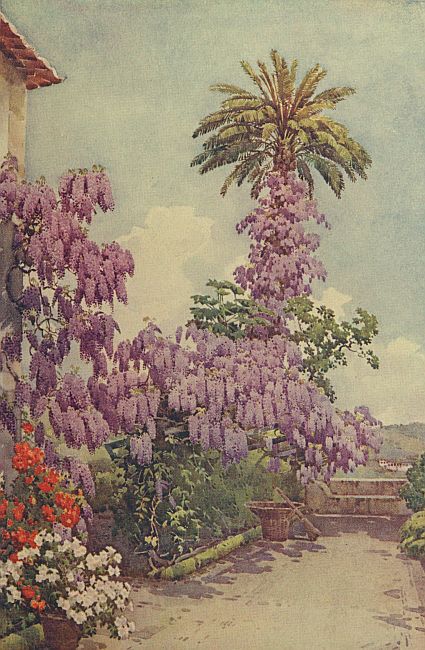

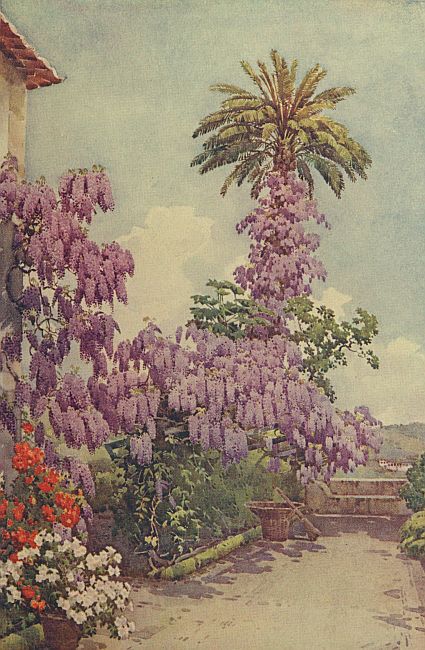

WISTARIA, QUINTA DA LEVADA

One garden I can recall which, though now neglected, still shows how it was once well cared for. Though the turf is no longer mown, and the box hedges have lost some of their trimness, the beds are still full of what were once treasured plants. The rose-garden no longer sees the knife of the pruner, but the trees grow and flower at their own sweet will, in careless disorder. It is a very lovely disorder, but it is always sad to see a garden once tended with the greatest care fall into other hands, who know nothing of the art of gardening. In spring the garden was full of jonquils and narcissi, and later on sparaxis and ixias. Near the house great bushes of Romneya coulteri were covered with their delicate white poppy-like flowers in summer. The plant seemed to have become thoroughly established, and threw up suckers in all directions, even through the paths of hard-beaten earth. From the grounds there are lovely views of the sea; and probably the garden looks its best when the agapanthus sends up its flowers in hundreds, and the hydrangea bushes are laden with their bright blue blossoms—as blue as the sky above or the sea below; or, again, in October, when the belladonna lilies are flowering in their thousands.

I think the love of gardening must have spread from these English gardens to the native cottage gardens. The English probably encouraged the cottagers to cultivate their plants, as from these little gardens come all the flowers which are to be bought in Funchal. A few flower-sellers will trudge seven long weary miles down to the town, nearly every day of the week, with a heavy basket of flowers on their heads, which they have collected from many a cottage garden. Naturally these flowers are not of the best, and it is very much to be regretted that some enterprising person does not start a shop or garden where cut flowers and plants could be bought. Many a time have I been asked where, in this land of flowers, good cut flowers can be procured, and the answer has had to be “Nowhere.” Would-be purchasers have to satisfy themselves with the contents of these baskets which are brought to the hotel and villa doors, and their contents are far from satisfactory. Beyond arum lilies, violets, and irises, a few indifferent daffodils and poor roses, there is little to be got. The women will complain that they have not a large sale for flowers, and it is in vain that I have told them that the real reason of it is that their flowers are so poor. Nosegays of a mixture of a dozen flowers, in as many colours, naturally find no market; but good flowers, I feel sure, would have a large and ready sale at reasonable prices.

The little gardens at Camacha are gay with common flowers: large bushes of white marguerites and trees of the early-flowering red Rhododendron arboreum give colour to the village even in early spring, and in summer it is naturally much more flowery. On every bank and hedgerow grow bushes of hydrangeas, with their flaunting blue blossoms, while great clumps of belladonna lilies transform the whole landscape, and the country seems to blush a beautiful rosy-pink.

The road between the two most popular summer resorts, Camacha and the Mount, runs through pine woods and long stretches of golden gorse to the Pico d’Infante, from where a very fine panorama of the Bay of Funchal is to be seen by turning aside a few yards from the road. Just beyond this point the path strikes the Caminho do Meio, another steep road leading down to the town. Near the eucalyptus and pine groves is the Quinta Bom Successo, one of the most beautiful of the outlying properties, which, from its elevation, escapes the summer heat, while its sheltered and sunny aspect makes it a pleasant residence through the winter months. The large grounds extend to the edge of the ravine, and a view of surpassing loveliness is suddenly brought before one at the very end of the terrace. The river roars and tumbles below, and the ragged cliffs throw deep mysterious shadows, while the more distant hills are wreathed with light transparent mists. The sides of the cliff have been transformed into a wild garden, as many plants have strayed from the garden proper, and have either seeded themselves or been cast over the precipice as discarded plants, where they have taken root and clung to life in some cranny between the stones. Within the grounds a rocky bank is covered with great stretches of the red Aloe arborescens, blue agapanthus and vast clumps of belladonnas, all growing in careless profusion. The garden has long been noted for its orchid-houses, where plants have been brought from all parts of the world, and also for the pine-houses, from which hundreds of pines are cut annually. Showing that, though at a comparatively high altitude, the garden is sheltered and warm, two natives of Burmah, the giant honeysuckle, which in May is wreathed with its strong-scented trumpets and the Burmese rose, both flourish, and in a few years have made astonishingly rapid growth.

The road to the Little Curral leads past a grove of Mimosa cornuta—which is smothered with its fluffy balls of yellow blossoms in early spring—to the valley itself. Every fresh turn of the steep zigzag path opens out fresh views, and at every step a new fern or little wild-flower is to be seen nestling between the damp mossy stones. Down near the bed of the river, which tumbles over great boulders in a roaring torrent after heavy autumn or winter rains, a large colony of arum lilies begin to unfold their pure white flowers in November, and continue in one unceasing succession until the late spring or early summer. The path winds up the opposite hillside, through a group of peasants’ huts, where yapping dogs and begging children for a few minutes mar the harmony and repose of the scene, and then again the path enters another silent valley, until the little village of the Mount is reached. A colony of countless little quintas, which have sprung up under the shelter and protection of the Church of Nossa Senhora do Monte, has of late years become a more favourite summer resort than Camacha. The air may not be quite so pure and cool, but the proximity of the town and the convenience of the funicular railway are, no doubt, responsible for its growing popularity.

The principal villa, the Quinta do Monte, formerly owned by an Englishman, has large grounds, planted with many rare trees and shrubs. The property has changed hands; the house is no longer inhabited, and the garden is falling into decay. As the grounds were always more pleasure-grounds than actual flower-gardens, it has suffered less than a smaller garden, which misses the personal care of its owner. The camellia-trees are an immense size, and have out-grown the little garden centring in a sundial, in which they were, no doubt, originally planted as small shrubs in beds with neat box hedges. Here are to be found tree-ferns, long rows of agapanthus, and a great plantation of mimosa-trees, which is quite a feature in the landscape in early spring, when they are laden with their balls of yellow blossoms.

In every direction in this district large clumps of the foliage of the belladonna lilies are to be seen in winter, on every bank, in every little garden: giving promise of their glories to come in the waning summer months. But in the grounds of Quinta da Cova they are probably to be seen at their very best, as here they have been more collected together, and broad stretches of them carpet the ground in thousands, beneath the chestnut-trees. I remember once hearing a traveller remark, who had passed through Madeira in August, on his way to the Cape, and returned again early in October, that when he first saw the island “it was all blue,” alluding to the effect of the agapanthus and hydrangea blooms, and when he returned it had changed, and was “all pink,” from the masses of belladonna lilies.