CHAPTER VIII

A RAMBLE IN THE HIGHER ALTITUDES

THE Church of Nossa Senhora do Monte is the starting-point of many an expedition made by those who have a wish to see more of the beauties of the island than can be done within the restricted area of Funchal. Should the Metade Valley be the point chosen, or the bleak Pico Ariero, with its enchanting views, or should the traveller be bent on a longer tour, and be proposing to make the little village of Santa Anna his headquarters for seeing the beautiful scenery of the north side of the island, the road up to a height of some 4,500 feet will be the same. Gradually the steep path winds its way through the fir woods, which in the early morning while the dew is still on them, exude a delicious aromatic scent, and the bushes of the little red Fuchsia coccinea and Rosa Benghalensis, with its small double pink flowers, and the clumps of belladonnas on the banks, which at first give the landscape the appearance of a ruined garden, are left behind, and the vegetation changes completely.

The pine woods consist chiefly of plantations of Pinus maritima, or pinaster, which have been planted for practical purposes, and have replaced the more beautiful chestnut woods, which were wantonly destroyed. These pines, being of rapid growth, are soon cut down, and provide timber for firewood, garden and vine trellises—in fact, are strictly utilitarian. The roots and stumps are burnt on the ground, and then possibly a crop of some sort is sown before the fresh pine seed is put in. This system has been the means of saving some of the more valuable and beautiful native trees, which at one time were ruthlessly felled; and even the forests in the interior, so necessary for the preservation of the water-sources, were threatened with destruction. Interspersed with the plantations of pine-trees are broad stretches of the common broom, which is sown extensively on the mountain-sides, either for the purpose of being cut down for firing, or to be burnt on the spot every five or seven years to fertilize the ground, and cause it to produce a single crop of wheat or batatas. The twigs and more slender branches are commonly used for making into faggots, and numbers of country-people, especially young girls and children, within reach of Funchal gain a scanty and hard-earned living by bringing daily into the town, often from great distances, bundles of giesta, as the natives call it, to be used for heating ovens and igniting the larger firewood. Doubtless the species was originally introduced into Madeira, though it is proved to have existed there for over 150 years, and now is so extensively diffused that it appears to be perfectly naturalized; in spring it floods the mountain-sides for miles with seas of its golden blossoms. The very fine and delicate basket-work peculiar to Madeira is manufactured from the slender peeled twigs of the broom.

Gradually ascending to the higher altitude, those who can tear their eyes away from the beautiful view of the Bay of Funchal and the curiously shaped hills above the villages of Santo Antonio and Santo Amaro will notice that by the roadside, in the moisture exuding from between the rocks, the innumerable ferns and the common foxglove, which at a lower altitude were so abundant, will gradually vanish. The myrtles, formerly so fine, are now unfortunately becoming almost scarce, owing to their injudicious destruction for ornamenting churches and adorning religious processions, after a height of 3,000 feet are no longer to be seen, and the country gradually becomes barren of vegetation. Rocks of basalt and red tufa appear, and the long sweeps of turf are only broken by large bushes of a heath, called, I believe, Erica scoparia, which, from being constantly eaten off by the mountain sheep and goats, gets a curiously distorted and stunted growth, though they eventually attain to a large size, and have such venerable-looking stems that they are suggestive of the dwarfed trees of the Japanese. Then comes the region of the Vaccinium Maderense, or padifolium, which varies in appearance according to the season. In winter it has crimson foliage, then it bears waxy bell-shaped blossoms, and in autumn is covered with almost black berries. From the situation in which it grows, exposed to the full blast of the north wind which sweeps over that stretch of country, it also has a bent and distorted appearance; and the dampness of the air—as, more often than not, at this altitude a white mist envelops the land—causes its stems to be covered with the Usnea lichen, which waves from one tree to another like masses of long green hair.

A turn in the road, at an altitude of some 4,800 feet, just beyond the rest-house at the bleak spot known as the Poizo, reveals a grand chain of mountains, with deep ravines running down to the sea. The traveller’s path will wind, in zigzag fashion, down the steep mountain-side, and gradually the Vaccinium will be left behind and the beautiful ravine of Ribeiro Frio is entered—thickly wooded with many varieties of the laurel tribe, which in their turn have their stems clothed with lichen.

To collectors of wild-flowers and ferns these mountain expeditions are a never-ending joy, as, according to the different seasons of the year, innumerable treasures are to be found. A ramble along the many levadas, or water-courses, will well repay the collector, as at all seasons, ferns, mosses, lichens, lycopodiums, and hosts of other moisture-loving plants, are to be found; while in June and July, when the wild-flowers are in all their glory, many rare and interesting plants will appear. The levada which runs through the Metade Valley was formerly the home of the Orchis foliosa, the orchis known everywhere as peculiar to Madeira, and its bright purple spikes brightened the dense masses of green. Of late years the plant has become scarce, probably ruthlessly uprooted by passers-by, or in order to be offered for sale in the town of Funchal. In describing this beautiful ravine, over which towers Pico Ruivo and the Torres, both some 6,000 feet in height, Miss Taylor, who was a great authority on native ferns, says: “Many rare and beautiful ferns will be found, growing both close to the running water and on the mountain-sides above the levada. Trichomanes radicans and Hymenophyllum Tunbridgense grow in great abundance; also Acrostichum squamosum, Pteris arguta, Asplenium umbrosum, Woodwardia radicans, and numberless others. Lichens of every sort and mosses—Lycopodium suberectum and Selaginella Kraussiana—seem to fill up every available space and crevice, and engage the hands and delight the mind of the collector.”

The more arid path to Ariero will not provide such treasures for the collector, who must content himself with the views of surpassing loveliness down to the deep, wooded ravines, which as the shadows begin to lengthen after midday, grow more mysterious-looking, getting grander and more beautiful as their deep blue turns to purple; and gradually the haze, which is certain to come before nightfall, fills the valleys and blots out the sea beyond. The rare orchis Goodyera macrophylla is said to be found in this district, with its beautiful pure white spikes, and here and there thickets of a low-growing indigenous, mountain ash, which in September bears fragrant white flowers, to be followed by brilliant scarlet berries in early winter.

From just beyond the rest-house at the Poizo a long turf ride of some four or five miles leads to the Lamaceiros, and is a welcome relief after clattering over the eternal cobble-stones. A long round, over country where seas of golden gorse, when it is in bloom, delight the eye and nose and make a beautiful foreground to the enchanting views, leads eventually past wooded glens, either over the Portella down to the village of Santa Cruz, or through the village of Camacha back to Funchal. A levada near the reservoir at the Pico d’Assoma is again rich in ferns, and Miss Taylor says: “The lover of ferns will perfectly revel in the wealth of lovely Hymenophyllums which clothe the stems of old laurels: here and there a mass of rock, perfectly cushioned with Hymenophyllum Tunbridgense; here and there a carpet of Hymenophyllum Wilsoni and Davallia Canariensis and Polypodium vulgare growing in masses on the trees. Nephrodium Oreopteris here grows in great abundance, the one place besides Pico Canario where it is to be found in Madeira. Nephrodium Fraenesecii and Nephrodium dilatatum here grow very large and perfect. The levada is fringed with Asplenium monanthemum, Cystopteris fragilis, and countless treasures. In July the Orchis foliosa blooms in great spikes of bright mauve. In this neighbourhood Acrostichum squamosum and Trichomanes radicans grow well.”

Probably nearly every levada in the island would repay exploring, but some are very inaccessible and require a steady head. One of the most beautiful is certainly that of the Fajao dos Vinhaticos, which could disappoint no one, and can be seen by staying at the village of Santa Anna, or, better still, at the engineer’s house on the levada itself.

On the north side of the island the vegetation is mostly the same. The rough and precipitous path which winds through the Boa Ventura Valley up to the Torrinhas Pass is clothed mostly with trees belonging to the laurel tribe. From the Pass itself some of the grandest views in the island are to be seen. The grandeur of the rocks and the splendid vegetation, the profusion of ferns and wild-flowers, hare’s-foot ferns hanging in long fringes from the stems of the evergreen trees, the variety of lichens, some of a deep orange colour, make the long ascent an endless source of delight to lovers of Nature, and, provided the weather is fine and the valleys free of mist, I know no more beautiful expedition.

If the traveller is returning to Funchal, he will gradually descend from this high altitude (close on 6,000 feet), down past the Church of Nossa Senhora do Livramento (Our Lady of Deliverance), through the valley of the Grand Curral, up the steep zigzag road opposite, and back to Funchal through the village of Santo Antonio. The region of the laurels and ferns, dripping with moisture, is left behind when the traveller turns his back at the top of the pass on the beautiful Boa Ventura Valley, and he will gradually return to the region of the heaths, pine woods, broom, and gorse.

When the village of Santo Antonio is reached, a marked change in the vegetation will be noticed. There are many Spanish chestnut-trees, whose fruit, being very popular with the natives, is sold in bushels in the town in autumn and early winter; and, the district being a very warm one, on the banks and in the hedgerows by the wayside the prickly-pear, agaves, and cactus will begin to appear, while large clumps of pelargoniums, sweet-scented geraniums, and lantanas have strayed from gardens and sown themselves in every direction. In April the beautiful Ornithogalum Arabicum, bearing its white starry blossoms with jet-black centres, may be seen growing wild, and I have been told that the pure white Lilium candidum is to be found in a wild state, though I have never come across it myself.

Between Santo Antonio and Santo Amaro the earliest strawberries which are brought into the market in Funchal are grown, making their appearance in favourable seasons late in February, though at that season they have little flavour, and generally only find favour in the eyes of the tourists, who are attracted by their inviting appearance as they are offered for sale in little fancy baskets. If some enterprising person would make some experiments with growing the plants on rather steep banks or slopes, as I have seen done elsewhere in temperate climates, in order that the plants may get the full benefit of the sun, I feel almost certain that far better early strawberries could be obtained: the sun would draw out that watery flavour from which they suffer. But it is always hard to induce a cultivator of any nationality to try new methods, and in vain one preaches, and is only met with pitying looks of incredulity and the remark that the crop, whatever it happen to be, has always been grown in the same way, however bad a way it may be, by the present owner, his father and his grandfather before him, and what was good enough for them is good enough for him.

There are more vines grown here than in any other neighbourhood, though, in consequence of the numerous attacks of disease—two scourges having several times threatened to completely destroy the vineyards: the dreaded Phylloxera insect, which attacks the roots of the vines, and also Oïdium Tuckeri, which settles on the leaves and fruit—together with the depression in the wine trade, vines are far less grown than formerly. Being trained over corridors—or latadas, as they are called in Madeira, pergolas, as they would be called in Italy—the effect is not only very pretty, but seems practical, as, being at a sufficient height from the ground, a labourer can work underneath them, and it is not uncommon to see another crop growing between the vines, though this practice of overstocking the ground is no doubt responsible for the failure of many a crop. The vines are pruned in February, though not to any great extent, and in April start into growth, and soon clothe the corridors with fresh young leaves and long twining tendrils. The flowers come in May, and by August the vines are laden with fruit ready for the harvest, which in early seasons begins in the lower regions late in August and continues, according to the altitude, until October.

The cultivation of vines and bananas, which were also grown at one time to some considerable extent, has been almost entirely replaced by that of sugar-cane, which, in consequence of the current rate fixed by the Government being a very high one, is at the present time a very profitable crop.

The cultivation of sugar-cane in the island dates from very early times, as in Cadamosto’s Voyages he writes that he visited the island in 1445, only twenty-six years after its discovery, and says: “Zargo caused much sugar-cane to be planted in the island, which has done well, and from which they have made sugar.” Mr. Yate Johnson says: “The cane is thought to have been introduced from Sicily about 1425, at the instance of Prince Henry. The first plantation was made on the site of the Cathedral, and did so well that the cane spread to other localities. Matters proceeded so rapidly in those days that in 1453 a mill was erected for crushing the canes by means of water-power.... Prince Henry was a good business man, and knew what he was about in making a bargain, for it was stipulated that he should receive one-third of all the sugar produced. Another stipulation was that the mill was to be placed where it would not be an annoyance to others, a regulation which, it is to be regretted, is not enforced at the present day. It is not known where this first mill was built, but it is more likely to have been in Funchal than anywhere else.” By 1498 the production of sugar is said to have increased to a very large extent, and then came troubles in the trade. The introduction of the cane to the West Indies and its extensive cultivation there caused increasing competition in European markets, and led to a heavy fall in price; but notwithstanding this, the cane continued to increase in Madeira, and by the end of the fifteenth century a large number of slaves were employed, both as labourers on the land and in the mills, which by now had increased in number to 120, on the southern side of the island.

Early in the sixteenth century disease came, in the form of a grub which eats into the cane, and the plantations suffered severely from its ravages, though many attempts were made to check its depredations. Possibly this, combined with the abundant production in the West Indies, caused the sugar-growing in Madeira to become so unprofitable that the mills dwindled down to only three in number, and the cultivation of vines for a time reigned supreme. This, in its turn, received so severe a check through the grape diseases in 1852, that the cane was once more restored to favour and again extensively planted. The cultivation increased, and new crushing machinery was imported from England; steam-power replaced the more primitive methods of water-power, or working the mills with bullocks only. After the revival, for a time the cane was only used for its juice, to be distilled into spirit (aquardente), but gradually, new sugar-making machinery having been imported, its manufacture was resumed and continued, until it has now reached the vast amount of about 2,500 tons per annum.

Different kinds of cane have been introduced, and if the cultivation is to be continued at the present enormous extent, artificial manures will have to be largely employed to prevent the soil becoming exhausted. The cane—I may say luckily—cannot be grown above an altitude of about 1,700 feet, or it would seem as if there would be no end to its cultivation, which by no means adds to the beauty of the island, and to my mind is an unsightly crop.

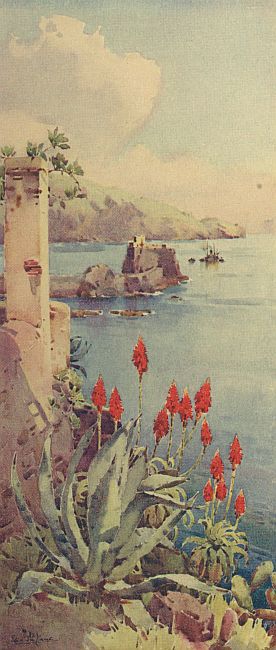

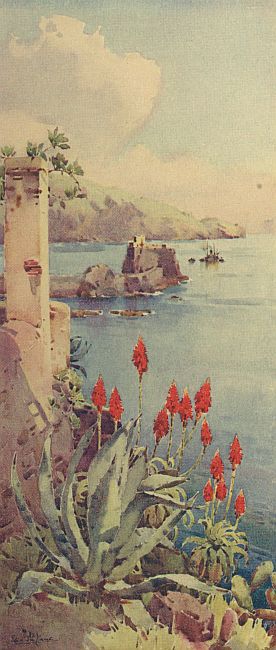

RED ALOES