CHAPTER X

CREEPERS

THE year opens in Madeira with a wealth of blossom, as in the month of January the bougainvilleas, for which Madeira is so justly famous, will be in all their flaunting beauty. It is true that the lilac-coloured Bougainvillea glabra will have already shed most of its blossoms, as it is a summer-flowering creeper, but it is replaced by so many other varieties that its pale beauty is forgotten. The brick-red coloured Bougainvillea spectabilis—which must have the full force of the sun upon it in order to bring out its colour to the best advantage, being apt otherwise to look a false colour—when grown over pergolas, or corridors as they are called in Madeira, or allowed to wander at will over a wall or bank, provides a gorgeous mass of colour. I had seen bougainvilleas in other countries, but only grown against walls, and closely cropped by shears, in order that the wood might be sufficiently ripened by the heat of the summer to insure its wealth of blossoms. Here such care is not necessary, and the natural beauty of the plant can be seen to full advantage where it has escaped the ruthless shears of the Portuguese gardener. Branches of blossom, ten, fifteen, or even twenty feet long, show the strength with which the plant grows; in fact, many a splendid specimen has had to be sacrificed, for fear it should undermine a terrace wall or shake the very foundations of a house.

To the landscape gardener who is fastidious as to the scheme of colouring in his garden, the placing of all the varieties of bougainvillea (called after the French navigator, De Bougainville) forms one of his chief difficulties. Each in itself seems too beautiful to be discarded; but, unless the garden is of considerable extent, I would recommend the owner of the garden to harden his heart and make his choice of the colour he prefers and stick to it, only growing the one variety in some great mass, be it as the gorgeous canopy of his corridor, or clothing his garden-wall.

Many persons give the palm for beauty to the deep magenta variety, speciosa, as it stands alone for colour. In all the kingdom of flowers I know no other blossom of the same tone of colour; it is a thing apart, this royal purple flower. No one who has seen the plant which covers the cliff below the fort can ever forget its beauty. Seen from the sea, it stands out like a purple rock in the middle of the city. By the middle of January it will be in all its gaudy, garish splendour, the admired of all beholders.

It can well be imagined how these two varieties—the one brick-red, the other deep magenta—would strike a jarring note in any garden if grown side by side, or even within sight of each other. And do not imagine that Madeira only boasts of these two coloured bougainvilleas in its winter season. From these two have sprung many others—seedlings, no doubt, hybridized in a country where the heat of the sun will ripen most seeds. So now there are rosy reds, lighter or darker, to choose from, shading through a range of colour which, like the beauty of its parents, seems to stand alone.

The plant has, I consider, two enemies in the island. One is the ordinary uneducated Portuguese gardener, who seems to think that the art of gardening consists in so closely pruning a creeper or shrub that all the natural grace and beauty of the plant is lost for ever, as often as not choosing the moment for this cruel treatment when the plant is in full flower. Though Nature has done her best to protect the plant from the hand of man, by giving it long, hooked thorns, which are exceedingly sharp, and, I believe, somewhat poisonous, even this has not been sufficient, and many a beautiful specimen have I seen maimed and dwarfed beyond repair in a few hours by an ignorant and overzealous gardener. Its second enemy is rats, which unfortunately have a great love for the bark on the stems of old plants, and many a plant narrowly escapes destruction at their hands, or rather teeth.

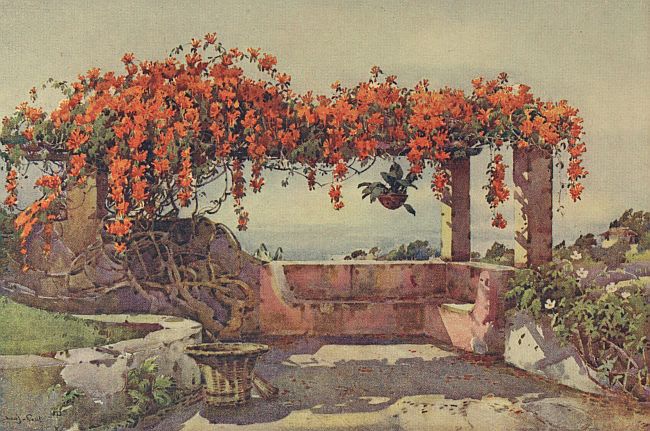

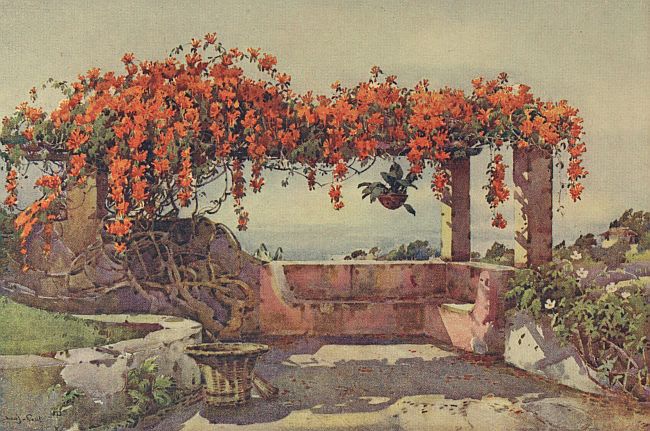

The second place in the list of creepers for the New Year must be given to the flaming orange Bignonia venusta, a native of South America, with its dense clusters of finger-shaped flowers. This has now become the commonest of all creepers in Madeira, and there is hardly a road in the neighbourhood of Funchal where all through the month of January there is not a stretch of wall bearing its gaudy burden, or a mirante (as the arbour or summer-house dear to the hearts of the Portuguese is called) without its roof of golden blossoms. There is a long list of bignonias and tecomas—a family so closely allied to each other as to be almost united—whose full beauty is for a later season; and only stray blossoms of the deep red Bignonia cherare, with its long yellow-throated trumpets, appear in the winter months, but sufficient to give promise of glories to come in the month of April.

BIGNONIA VENUSTA

In the same month the close-growing Tecoma flava will become wreathed with its golden-yellow trumpet flowers, clothing many a wall and straying across tiled roofs, as it is so neat and clinging in its habit that it never becomes so heavy a mass as to damage buildings. Its companion at the same season is Tecoma Lindleyana, bearing large mauve trumpet flowers, with a throat of a lighter shade. The individual flowers are of extremely delicate texture, and are beautifully veined with a slightly darker shade of purple. Yet another tecoma unfurls its blossoms late in the month of April, but is not so often met with as the two former varieties, possibly because the plant, when out of flower, presents rather an unsightly and straggling appearance; but no one can fail to admire the pure white and yellow-throated blossoms of this Tecoma Micheliensis, as it is most commonly called, though I believe it has a second, and possibly more correct, name.

For May and June is reserved, probably, the most beautiful of all the tecomas, jasminoides. The plant is an ornament at all seasons; its beautiful glabrous foliage seems to retain its freshness at all seasons of the year, and when the plant is covered with its bunches of large white blossoms, each with its deep red-purple throat, which seems to reflect a shade of purple on to the white petals, it is one of the most beautiful of all creepers.

From the list of winter creepers the Thunbergia laurifolia, with its bunches of grey-blue gloxinia-shaped blossoms, cannot be omitted; though the beauty of the plant is somewhat spoilt by the habit of the dead blossoms hanging on instead of falling, and marring, by their brown, shrivelled appearance, all the freshness of the newly developed flowers. The plant always recalls to my mind the reason given by the Japanese for not admiring the national flower of England—the rose—as they complain that it clings with ungraceful tenacity to life, as though loath or afraid to die, preferring to rot on its stem rather than drop untimely; unlike the blossoms of spring, ever ready to depart life at the call of Nature. Such is certainly the case with thunbergia. The creeper is also a dangerous poacher, and, unless kept within bounds, will soon smother and overwhelm any shrub or tree that it may take possession of, though never in Madeira attaining to the vast proportions that it assumes in Ceylon or other tropical countries, where it takes possession of even the tallest forest-trees, and hangs its long trailers from one tree to another, and on and on again, in one dense tangle. The white variety does not seem to have been introduced to Madeira, and its pure white blossoms recall gardens in St. Vincent and other West Indian islands.

Yet another creeper whose flowering season belongs to the winter months is the scarlet passionflower, Passiflora coccinea. By the end of January the plant will be covered with a few fully opened flowers, many half-developed flowers and innumerable buds giving promise of its future splendour. On first acquaintance, one is deceived into thinking that in a few days’ time the plant will be a sheet of scarlet blossoms, but such is not the case: each individual flower is short-lived, and by the time the half-developed blossoms have opened, the fully expanded blooms of yesterday have vanished. Thus its flowering season is a prolonged one, but it never attains to any very gaudy splendour.

By the last days of March the racemes of that most beautiful of all creepers, Wistaria chinensis, or sinensis, will have begun to lengthen, and gradually clothe the whole plant with a pale purple canopy. The vine—as it is called the grape-flower vine, from the resemblance of its blossoms to a bunch of grapes—is a native of China and Japan, and also of parts of North America, which accounts for the fact that it received the name of wistaria (by which it is known all over the Western world) from one Caspar Wistar, a medical professor in the University of Pennsylvania. In Japan the plant is known as fuji, and is so universally admired that, in common with many other flowers, it is made the excuse for many a flower-feast, when hundreds, thousands, and even tens of thousands of pleasure-seekers will hold their revels, or sit quietly sipping their tea under a roof of the royal fuji. Though in Madeira it is not the fashion of the country to hold flower-feasts, or to make flowers the theme of poems and plays, or to regard wistaria as an emblem of gentleness and obedience, as is the case in its Eastern home, yet in this land of its adoption it comes in for its full share of admiration. Corridors and walls which have been passed by unnoticed through the winter months, having been only clad with the long, bare, leafless branches, the last leaves having fallen early in December, suddenly become transformed, and for a few short days—all too short, alas!—become the centre of attraction in the garden. Like in Japan, the wistaria season begins with the white wistaria, which has been christened in the Western world Wistaria Japonica, and “it would seem as though this modest white wistaria had been allowed by Nature to bloom so early, for fear she should be overlooked and not appreciated when her more showy successor flings her purple mantle over the land.” There are good specimens of this early white variety in the gardens of the Quinta da Levada and the Quinta do Val.

The variety known as Wistaria multijuga, for which Japan is so justly famous, as it appears to be the only country where its full beauty can be seen, has been introduced with but little success to the island. It is true that it will grow, and grow strong, but its long racemes of thin, pale, washed-out-looking flowers are but a sorry sight to those who have ever seen the far-famed Kameido Temple grounds in Tokyo, when the vines, with their long purple tassels, often over three feet in length, clothe the long trellises and almost smother the guests who sit feasting beneath them, gazing across at the long vista of mauve blossoms reflected in the water below. But even in Japan this far-famed multijuga variety is only to be met with in certain districts and as a cultivated form, and is never seen clambering from tree to tree in a wild state, like the chinensis variety. The wistaria season closes as well as opens with a white-flowered form both in Japan and Madeira, as the variety known as macrobotrys, with its very long racemes of white blossoms, prolongs the beauty of the fuji feast at the celebrated Kameido Temple; and here in Madeira, though only one or two plants of it exist, it is the last to retain its beauty.

The summer months will have their own creepers, though not such showy ones as the winter and spring months; but if they are lacking in colour, many of them atone for that by their delicious fragrance. To these belong Rhyncospermum jasminoides, or Trachelospermum, as I believe it is more correctly called, whose white starry flowers fill the whole air with their almost overpowering scent. The plant is a native of China and Japan, where it may be seen growing in a perfectly wild state in hedgerows. There is another variety called angustifolium whose blossoms are much the same, but the foliage differs, and this kind is said to prove hardy when grown against a wall in the South of England. The well-known Stephanotis floribunda, called in its native country the Madagascar chaplet flower, unfurls its heavy-scented waxy blossoms in the summer months. Allamanda schotii, hoyas, with their clusters of waxy red blossoms, mandevilleas, and hosts of others, are seldom seen in their beauty by the English owners of gardens.