CHAPTER XI

TREES AND SHRUBS

THE list of indigenous and naturalized trees and shrubs growing in Madeira is such a long and varied one that it is not surprising that Captain Cook, in his account of his first voyage, should have said: “Nature has been so liberal in her gifts to Madeira. The soil is so rich, and there is such a variety of climate, that there is scarcely any article, either of the necessaries or luxuries of life, which could not be cultivated there.”

The place of honour among the island trees must be given to those belonging to the laurel tribe, of which there are a great number, and splendid specimens still remain in the country, survivors of the wholesale destruction of the primeval forests. To this tribe belongs the til, one of the most beautiful of evergreen trees, its shiny green leaves contrasting admirably with the light grey bark of its stems. The old trees grow to a very large size, and in the Boa Ventura Valley and along the road to Sao Vincente there remain some grand old specimens, the immense girth of whose trunks speaks for itself of their great age. The true name of this so-called laurel appears to have been a matter of some uncertainty, as Miss Taylor, in “Madeira: Its Scenery, and How to See It,” classes it as Oreodaphne fœtens, describing it as “the grandest of native trees”; while Mr. Bowdick, in 1823, says: “The til has been confounded with Laurus fœtens, from the strong, disagreeable odour of the wood when first cut. It is very valuable for its timber, being extremely hard and tough. It would appear that the Portuguese call both Laurus fœtens and Laurus cupuleris til, as they say there are two kinds of til, and both are equally fetid.” In the damper regions beautiful lichens grow luxuriantly on the stems of the trees, and ferns have found a home in the cracks of the bark. The value of its timber has no doubt been responsible for the destruction of the trees. When polished, the wood is of a very dark colour, almost as black as ebony.

The vinhatico, whose wood is the mahogany of Madeira and closely resembles it, is another of the native trees, and again I find it classed as Laurus indica by Mr. Bowdick, who describes it as one of the island’s most valuable products, while Miss Taylor describes it as Persea indica. The wood, when cut, is of a deep red colour before being polished. It is a fine forest tree, and has, as a rule, light green foliage, though it occasionally turns crimson. It has given its name to one of the most beautiful bits of scenery in the island, as the Levada dos Vinhaticos, running above the village of Santa Anna, passes through some of the grandest scenery in Madeira. Professor Piazzi Smyth has gone so far as to assert, in “Madeira Spectroscopic,” that some of the largest ships of the Spanish Armada were either built of, or internally decorated with, the wood of the tils and vinhaticos of Madeira. This would appear to be a flight of imagination, or a revelation of the learned man’s inner consciousness, as it is difficult, if not impossible, to find any grounds for such an assertion, there being no document extant stating what timber was employed for the building of that celebrated fleet.

The laurel familiar to us under the name of Portugal laurel, Cerasus lusitanica, assumes the proportions of forest trees, and when I saw it in spring, covered with its long racemes of creamy-white flowers, it quickly dispelled the aversion with which I had always regarded the stumpy, blackened specimens pining under the smoky atmosphere of suburban shrubberies.

Laurus Canariensis is a fragrant form of laurel, and the country-people extract oil from its yellow berries.

Picconia excelsa, the Pao branco of the Portuguese, is generally to be found in the same districts as the til-trees, and attains to a height of forty or fifty feet. Its hard, heavy white wood, being in great demand for the keels of boats, is very valuable. Like many other native trees, it is for this very reason rapidly becoming scarce, as its destroyers, having no thought for the future, omit to cultivate it from seed, which grows readily.

The Clethra arborea, or lily of the valley tree, as it is called by the English, on account of the resemblance of its spikes of creamy-white flowers to those of a lily of the valley, fills the whole air with its delicious though somewhat heavy fragrance when the tree is in flower in summer. Yet another fragrant tree peculiar to Madeira is the Pittosporum coriaceum, which has been christened the incense-tree, as early in April the air, especially near sundown, is filled with the almost overpowering scent of its clusters of small greenish-white flowers. The bark is very smooth and even, and of a light ash colour. The tree is now somewhat rare in its natural state, but is frequently seen in gardens, where it has no doubt been transplanted from its original home among the rocks, as Mr. Lowe, in his “Flora of Madeira,” remarks how he only noticed it growing on high rocks or in inaccessible places.

One of the first trees which is sure to strike the eye of the new-comer is the dragon-tree, or Dracæna draco, on account of its peculiar growth. From having been a common tree on the island it has now become a rare one in its native state; in fact, the only ones I have ever seen under those conditions are a few sole survivors on the rocks beyond the Brazen Head, where formerly they grew in great numbers. Now by their quaint growth they give a distinctive feature to many a garden, and it is consoling to know that they are easily raised from seed. Mr. Bowdick, in writing of the tree, says: “The dragon-tree was considered by Humboldt as exclusively indigenous to India, but I am inclined to think it is also natural to Porto Santo, and perhaps to Madeira—not from the few specimens which now remain on these islands, but from the account of Cadamosto, who visited Porto Santo in 1445, and writes that the dragon-trees of Porto Santo were so large that fishing-boats capable of containing six or seven men were made out of the trunks, and that the inhabitants fattened their pigs on the fruit; but he adds that so many boats, shields, and corn-measures had been made out of them, that even in his time there was scarcely a dragon-tree to be seen in the island.”

The stem exudes a gum, and the following account of the means of collecting it is taken from a Portuguese account of “The Discovery of Madeira,” written in 1750: “All over the island grows a tree from which the dragon’s blood is procured. This is performed by making incisions in the bark, from whence the gum issues very plentifully into pots hung upon the branches to receive it. The people use it as a sovereign remedy for bruises, to which they are very much exposed by traversing their rocky country; and this, with one panacea more, completes their whole materia medica—that is, balsam of Peru, imported from the Brazils in small gourds by their annual ships. These two, they imagine, have power to cure almost all disorders, especially those that are external.”

Among other native trees, the beautiful Taxus baccata and the Juniperus oxycedrus, with its great spreading silvery-green branches, cannot be omitted. The former has become almost extinct, and the juniper is also becoming rare, from the reckless way in which the trees have been cut to be used for torches. The fragrant red wood is split into lengths, and several bound together, for this purpose. In gardens their dense growth makes them admirably suited to form an arbour, in the absence of the ubiquitous mirante, as they provide shelter from the wind and perfect shade.

Another evergreen tree, which, though not a native tree, is very commonly to be seen in and about the town of Funchal, is the Ficus comosa, which, as its name implies, is a beautiful tree, though, from its having such far-spreading hungry roots, it is more suited to the roadside than to gardens. A peculiarity of the tree is the slenderness of its stem in comparison to the immense length and weight of its very spreading branches; its bark is a very light grey colour, and is in admirable contrast to the very smooth and shining leaves, which are dark green above and pale beneath, produced in masses on the slender rather hanging branchlets. Two very fine specimens of these trees stand alone on the Rodondo, near the Quinta das Cruzes, from where a very fine view of the town is to be seen from under their immense spreading branches.

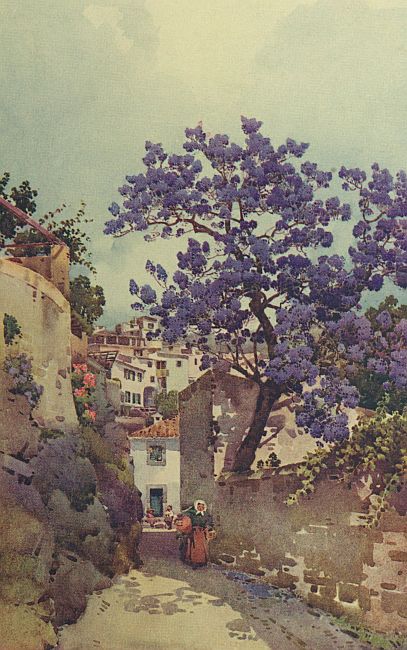

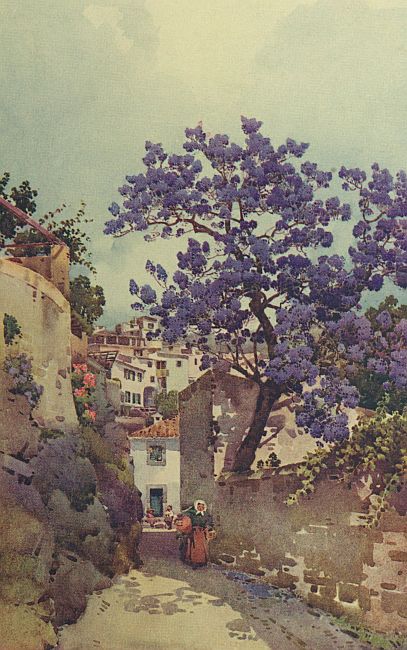

JACKARANDA-TREE.

The camphor-trees are at their best in spring, when they are covered with their delicate young green shoots, generally of a very light green, but occasionally having brilliant red shoots. The trees attain to a large size, though not assuming the gigantic proportions which they reach in their native land, Japan. That most uninteresting of all trees—the plane-tree—has been planted along the beds of the rivers in the town; and the oaks are in almost perpetual foliage, as the young leaves appear before the old ones have really fallen.

Grevillea robusta is common in gardens, where, having shed its leaves in winter, the trees are showy in the early summer months, being covered with yellow flowers; but the palm for flowering trees must be given to the Jacaranda mimosafolia, a native of Brazil. Having also shed its long fern-like foliage in the late winter months, early in May the tree bursts into a cloud of blue blossoms, almost as blue as the sky above. The tree is a fairly common one in and about Funchal, and the “blue trees,” as they are generally called, are the admired of all beholders during the few weeks they are in bloom. Nature has done well in ordaining that the foliage should fall before the tree blossoms, as the full beauty of the flower is thus seen unshrouded by leaves.

The list of flowering trees is a long one, but I cannot help mentioning a few others which are ornaments to the gardens when in bloom. The dark red of the Schotia speciosa blossoms also adorn a leafless tree. The tree, which was called after a Dutchman, one Richard van der Schot, in its native country—subtropical Africa—is commonly known as the Kaffir bean-tree, no doubt because its blossoms are more suggestive of bunches of red seeds or beans than flowers.

There are a few specimens of the gorgeous Poinciana regia, which flowers in summer; its peculiar flat, spreading branches are easily recognized. No one who has ever seen these magnificent trees in all their gaudy splendour in tropical regions can ever forget their beauty. They deserve their name, the royal peacock flower, though they are more commonly known as flamboyant-trees, from the likeness of their leafless branches, clad with brilliant orange-red nasturtium-like blossoms, to flaming torches. In Madeira the tree does not attain to its full beauty, as possibly the difference between the climate of its native home—Madagascar—and that of Madeira is too great. Here the less showy variety, known as Poinciana pulcherrima, thrives better.

At the same season the uncouth growth of the bare and leafless frangipani or plumeria trees bursts into blossom—white, cream-coloured, or pale pink—and fills the air with its heavy fragrance, recalling the oppressive, almost stifling, atmosphere of Buddhist temples in Ceylon, where frangipani blossoms are almost regarded as sacred to Buddha, and are always called “temple flowers.”

Of the coral-trees there are several varieties: Erythrina corallodendron, a native of the West Indies, has large spikes of deep red blossoms on leafless light grey stems; and Erythrina cristagalli, a native of Brazil, also bears scarlet blossoms. Besides the flowering trees, there are so many shrubs which contribute such a wealth of colour to the gardens, especially in the winter months, that it is hard to decide which are most worthy of notice. The gaudy orange-coloured Streptosolen Jamesonii, which was only introduced into Madeira a comparatively short time ago, has now become one of the commonest, but none the less beautiful, of winter-flowering shrubs. Like many other plants which I had only known pining in the unfavourable atmosphere of an English greenhouse, it is almost impossible to recognize the streptosolen of the greenhouse, with its dull orange and yellow blossoms, as the same plant when grown in the sunshine of Madeira. The soil is no doubt partly responsible for the difference in colour—a fact I have noticed with many other plants, but certainly in the case of streptosolen the change is most remarkable—and the intense brilliancy of its large heads of blossom attract the attention of all new-comers to the island. The shrub is sometimes known as Browallia Jamesonii; and a blue variety which has lately been introduced from the Cape seemed to closely resemble the family of browallias. Should it prove to have as vigorous a constitution as the orange variety, it will be another great acquisition to the island, as its blossoms are of a deep clear blue.

Astrapæa pendiflora, or tassel-tree, as it is often called, from the resemblance of its great balls of pink blossoms hanging on a long slender stalk, has handsome foliage, and assumes the proportions of a large shrub or small tree in a short time, as it appears to be of very rapid growth. I find it difficult to share the almost universal admiration that it awakens when in flower, as its beauty is much marred by the tenacious habit of its dead blossoms, which cling to life to the bitter end, and spoil all the freshness of the newly developed blossoms. The balls of blossom, in shape reminding one of huge guelder roses, start by being a greenish-white, which gradually turns to a deep dull pink, and in death to a most unsightly brown. Astrapæa viscaria attains to the size of a large tree, and in April bears a burden of pink blossoms, also in round balls; it is a native of Madagascar, which seems to be the home of so many of the most beautiful flowering trees.

Among purple flowering shrubs, for the beauty of its individual flowers and purity of colour, Lasiandra or Pleroma macrantha, with its large deep violet-purple blossoms, deserves a place in every garden. The plant cannot be reckoned amongst the most showy of the flowering shrubs, as it does not bear many blossoms fully expanded at the same time, though, as the flowers are very freely produced at the ends of the branchlets, its flowering season is a prolonged one. The plant appears to be a native of Brazil, which is another home of many of the most beautiful of flowering shrubs.

Wigandia macrophylla attains to the size of a small tree; its large, loose heads of lilac-purple flowers, somewhat resembling paulonia blossoms, and its handsome foliage, combine to make it a most ornamental plant and a valuable acquisition all through the winter and early spring. To Brazil we owe another favourite shrub, Franciscea latifolia, as it is commonly called, though it appears to belong to the Brunsfelsias, a family of shrubs called after one Otto Brunsfels, who was first a Carthusian monk and afterwards a physician. The clear lilac blossoms have a distinct whitish eye, and as they fade, turn to a greyish-white, so the shrub appears to bear white and lilac blossoms at the same time. The blossoms are deliciously fragrant, though many people consider their scent to be too strong and overpowering. A well-grown specimen attains to eight or ten feet, and has pleasing shiny green foliage.

The light crimson-flowered Hibiscus rosa sinensis, which ornaments most gardens in tropical or subtropical regions, has also found a home in Madeira, and the long white trumpet-flowering Brugmansia suaveolens, more commonly called daturas, natives of Mexico, have found so congenial a home that the shrub may almost be considered to have become naturalized. Growing at the bottom of many a ravine rich in vegetation, the shrub will appear to be in a perfectly wild state, bearing a fresh crop of leaves and blossoms with every new moon, and filling the air at nightfall with their heavy scent.

The blossoms of the daturas are known as bellas noites by the Portuguese, though the night-scented flowers of Cestrum vespertinum seem to share the name with them; occasionally, it is true, the latter are deemed masculine, and are therefore called boas noites. The following interesting description of Brugmansia or Datura suaveolens is taken from Mr. Lowe’s “Flora of Madeira,” written in 1857: “The flowers are slightly fragrant by day, but much more powerfully and diffusedly so after sunset and through the night, when, by moonlight, they display an almost radiant or phosphorescent snowy-whiteness, and expand more fully, falling into elegant thick horizontal rows or flounces on the trees or bushes. Nothing can exceed their grace and loveliness when in full luxuriance and perfection, which it may be said to attain at intervals of four to five weeks continuously, from June to November or December. The tree is esteemed noxious, and therefore in Madeira of late years has been banished from gardens and near proximity to houses. This idea perhaps originated from an accident which occurred some forty years ago, when two or three children, having eaten a few of the seeds, escaped by timely medical assistance, with no further harm than the effects of an overdose of Atropa belladonna. Still, there is something perceptively oppressive in the evening, in too long or close inhalement of the powerful aromatic fragrance of the flower.”

The peculiar flowers of Strelitzia regina, introduced to Europe from South Africa during the reign of George III., and named, in honour of Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburgh Strelitz, never fail to attract admiration. The plant is also called bird of paradise flower and bird’s-tongue flower—both suitable names, as the gaudiness of its blue and orange flowers must have been responsible for the former, while the resemblance of the flower to a bird’s head with a bright blue beak shows its likeness to the latter. The plant has long, narrow, oblong leaves, of a dull greyish-green, of a peculiarly tough texture, and a good clump some four or five feet high is very ornamental. Strelitzia augusta, as its name implies, is of more majestic growth. It has large foliage, not unlike a banana, and clumps attain to twelve or fifteen feet in height. The blossom is more curious than beautiful, being of so dark a purple as to be almost black; but, for the sake of its foliage, it is always worth a place, and may well be called a noble plant.

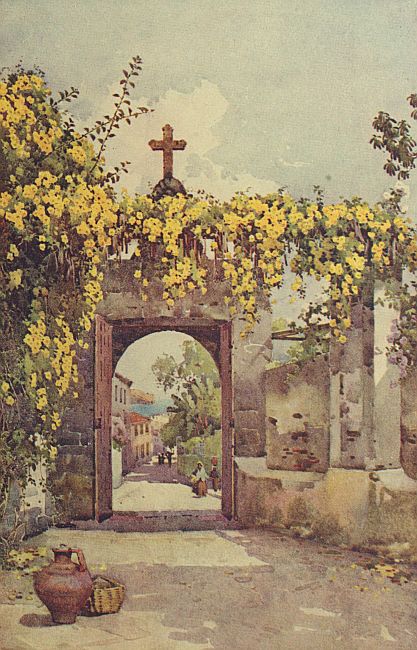

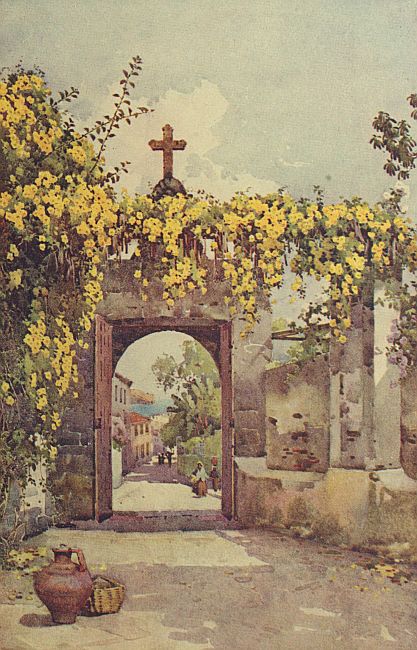

A CHAPEL DOORWAY