CHAPTER II

PORTUGUESE GARDENS

I HAVE often been asked whether the Portuguese have any distinctive form of gardening, and in answer I can only say that, though there is no attempt to compete with the grand terraced gardens of Italy or France, or the prim conventionality of the gardens of the Dutch, still the little well-cared-for garden of the Portuguese has a great charm of its own. Here, in Madeira, their gardens are usually on a very small, almost diminutive, scale, according to our ideas of a garden. In the mother-country, where they probably surround more imposing houses, they may attain to a larger scale, but of that I know nothing.

The love of gardening, unfortunately, seems to be dying out among the Portuguese in Madeira, and many a garden which was formerly dear to its owner, each plant being tended with loving hands, has now fallen into ruin and decay. The little paths, neatly paved with small round cobble-stones of a pleasing brownish colour, have become overgrown and a prey to the worst pest in Madeira gardens, the coco grass, which is enough to break the heart of any gardener once it is allowed to get possession; its little green shoots seem to spring up in a single night, and the labour of yesterday has to be again the work of to-day if the neat, trim paths so necessary to any garden are to be kept free from the invader. Or the box hedges, which were formerly the pride of their owner, have lost their trimness and regularity from the lack of the shears at the necessary season, and the garden only suggests departed glories.

Luckily, a few of these gardens still remain in all their beauty, and the pleasure their owners display in showing them speaks for itself of their true love of gardening.

The plan of the garden is usually somewhat formal in design, and as a rule centres in a fountain or water-tank, which serves the double purpose of being an ornament to the garden and of supplying it with water. The entrance to the garden is certain to be through a corridor, with either square cement and plaster pillars, or merely stout wooden posts, which carry the vine or creeper-clad trellis. The beds are not each devoted to the cultivation of a separate flower, as would be the case in an English garden, but single well-grown specimens of different kinds of plants fill the beds. Begonias, in great variety, tall and short, with blossoms large and small, shading from white through every gradation of pink to deep scarlet, form a most important foundation for every Portuguese garden; as, from their prolonged season of blooming, some varieties seeming to be in perpetual bloom, they always provide a note of colour. Pelargoniums, allowed to grow into tall bushes, in due season make bright masses of colour, the velvety texture of their petals seeming to enhance the brilliancy of their colouring. Fuchsias in endless variety, salvias red and blue, mauve lantanas, scarlet bouvardias, and Linum trigynum, with its clear yellow blossoms, help to keep the little gardens gay through the winter months. The latter, though commonly called Linum, is a synonym of Reinwardtia trigynum and a native of the mountains of the East Indies.

Last, but by no means least in importance, come the sweet-smelling plants, essential to these little miniature gardens. Olea fragrans, or sweet olive, also called Osmanthus fragrans, must be given the palm, as surely its insignificant little greenish-white flower is the sweetest flower that grows, and fills the whole air with its delicious fragrance. Diosma ericoides, a well-named plant—from dios, divine, and osme, small—ought perhaps to have been given the first place, as it will never fail at every season of the year to bring fragrance to the garden. The tender green of its heath-like growth, when crushed, yields a strong aromatic scent, and no Portuguese garden is complete without its bushes of Diosma. If allowed to grow undisturbed, it will make shrubs of considerable size, and in the early spring is covered with little white starry flowers; but as it bears clipping kindly, it is especially dear to the heart of the Portuguese gardener, who will fashion arm-chairs, or tables, or neat round and square bushes, in the same way as the Dutch clip their yew-trees. Rosemary also ranks high in their affections, not only for its sweet-smelling properties, but also because it can be subjected to the same treatment. Sweet-scented verbenas are also favourites, and in spring the tiny white flower of the small creeping smilax suggests the presence of orange-groves by its almost overpowering scent.

Camellias, white and pink, single and double, are favourite flowers, but as a rule the shrubs are subjected to drastic treatment and cut back, so as to keep the plants within bounds and in proportion to the size of the garden. Here and there a leafless Magnolia conspicua adorns the garden with its cup-like blossoms in the early spring, and a few other shrubs are permitted within the precincts of the garden. Franciscea, with its shiny green leaves and starry blossoms, shading from the palest grey to deep lilac, according to the time each bloom has been fully developed, should have been included in the list of sweet-smelling plants, as it has an almost overpoweringly strong scent. The bottle-brush, Melaleuca, with its strange reddish blossoms, showing how aptly it has been named, and the pear-scented magnolia, with its insignificant little brownish blossoms, are all favourite shrubs.

Various bulbous plants seem to have made a home under the shelter of their taller-growing companions, and in February, freesias, which in this land of flowers seed themselves, spring up in every nook and cranny; also the unconsidered sparaxis, whose deep red and yellow striped flowers are hardly worthy of a place. But the bright orange tritonias and deep blue babianas are highly prized, and in May the red amaryllis adorn most of the gardens, in company with the rosy-white Crinum powellei. The delicate Gladiolus colvillei, known in England as the Bride and under various other fancy names, open their pale pink-and-white spikes of bloom early in May. A few plants of carnations are treasured, as they are not easy to grow. Rose-trees are given a place, many being such old-fashioned varieties that I could not find a name for them; while the walls of the garden may be clad with heliotrope, which seems to be in perpetual bloom, or Plumbago capensis, whose clear blue blossoms cover the plant in great profusion in late autumn and spring. In summer the yellow blossoms of the Allamanda Schotti appear, and later in the year the waxy-white Stephanotis floribunda and Mandevilleas will all in turn be an ornament to the garden, though in the winter months their glossy green foliage will have passed unnoticed.

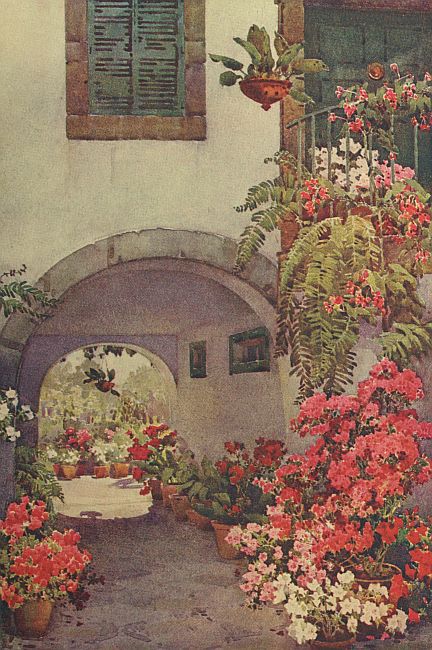

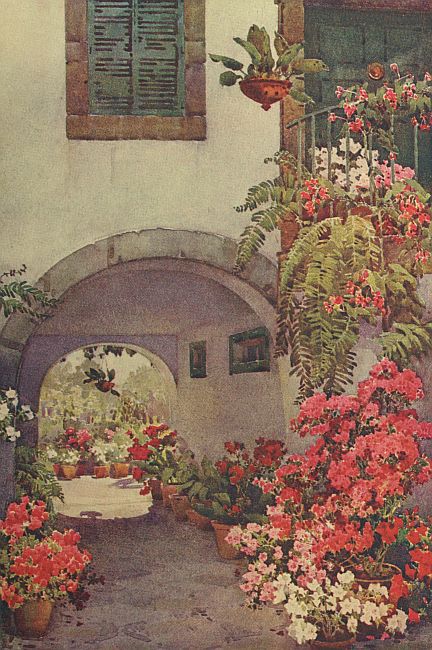

AZALEAS IN A PORTUGUESE GARDEN

I consider that Azalea indica is the plant which is most valued by the Portuguese. In the cared-for garden it is given a most conspicuous place, either planted in the open ground in partial shade, or more frequently kept in pots, and tended with the greatest care. In February and March through many an open doorway a glimpse may be caught of a group of gay-coloured azaleas, even in little humble gardens which at other seasons of the year are flowerless. The whole horticultural energy of the owner of the little strip of garden has been centred in the loving care bestowed on his few treasured azaleas. A tiny plant, not more than a few inches in height, will be far more valued than its overgrown neighbour, if it should happen to be some new variety, possibly only bearing a few blossoms, but perfect in form, of immense size, single or semi-double, of a brilliant rose-red, clear pink, salmon colour, or pure white. The culture of azaleas does not seem to be peculiar to the natives of Madeira, as from Oporto come numerous sturdy little trees of all the most highly prized varieties. The effect of well-grown specimens in pots, arranged along the stone ledge of the garden corridor, or grouped round the stone or, more correctly speaking, plaster seat, which generally finds a place in all these gardens, is very pleasing, and well repays the care bestowed on the plants all through the heat of the summer months.

A corner of the garden must be devoted to fern-growing, without which no garden in Madeira is complete. In the gardens of the rich a little greenhouse, or stufa is considered necessary for their successful cultivation, but in many a shady, damp corner of a humble cottage garden have I seen splendid specimens of the commoner ferns grown without that most disfiguring element. Perfect shelter from wind and sun is, of course, necessary, and sometimes, where no other shelter is available, the dense shade of a spreading Madeira cedar-tree is made use of, and from its branches will hang fern-clad pots. Or a little arbour is formed of that most useful of shade-giving creepers, the native Allegra campo, or Happy Country. The plant is also sometimes called Alexandrian laurel, though for what reason it is hard to know, as it has no connection with the Laurel family, but is Ruscus racemorus. The plant throws up fresh shoots every winter, which in their early stages appear like giant asparagus, and grow and grow until sometimes they reach fifteen or twenty feet in length before the fresh pale green leaves develop. By the spring the young leaves have unfurled, and provide a canopy of delicate green through the summer. The growth of the previous year can either be cut away, or if retained, in late spring, little greenish-white flowers will appear on the underneath of the leaves. The plant is a native of Portugal, but may be found in a wild state in Madeira. It is also known under the name of Danæ racemosus. One of the Polypodiums, called by the Portuguese Feto do metre, or Fern by the yard, seems to be first favourite, and splendid specimens are to be seen, each frond measuring one to two yards in length. Gymnogrammes, or golden ferns, are also much prized, and the Asparagus sprengerii has during the last few years found many admirers, with its long sprays rivalling in length the Feto do metro. Adiantums and all the commoner ferns are given a place, according to the taste of their owners.

I cannot close this chapter without a few words on the subject of the neat devices made by the Portuguese out of canes or bamboo, for training plants. In some instances it may be overdone, and one cannot always admire rose-trees trained on to bamboo frames in the shape of fans, crosses, or even umbrellas; but the little arched fences as a support to lower-growing plants are used with very good effect. I have copied the idea in England with some success for training ivy-leaved geraniums in large pots or tubs, by planting four rather stout bamboos or canes, two feet or more in height, in the pots, then slipping four pieces of split cane into the hollow ends, and either forming four arches, by inserting each end of the split length into the hollow, or else a pagoda-like effect can be made by taking the split canes into the middle, and then slipping all four ends through a hollow piece of cane a couple of inches long. Side arches can be made in any number, according to the requirements of the plant or the fancy of the gardener, by making incisions in the stout bamboos at any distance from the ground, and inserting the ends of the split canes. Old carnation plants, or seedlings which bear many flower-stems, may be very successfully and neatly supported in this way.

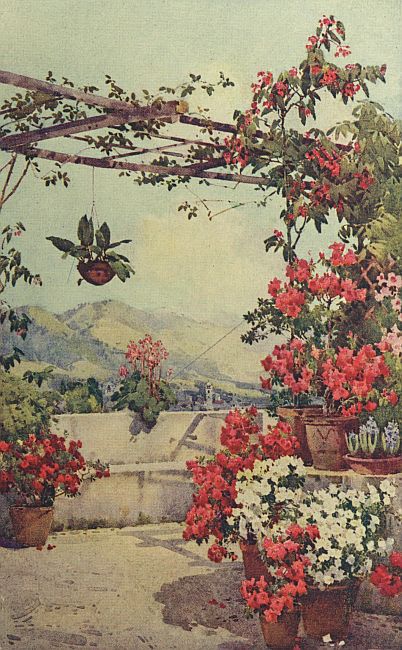

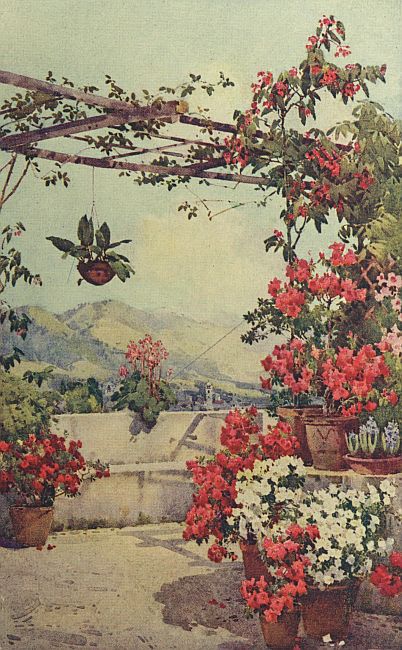

AZALEAS, QUINTA ILHEOS

Another contrivance for the increase of their rose-trees struck me as original, and worth mentioning, and possibly imitating, by those who garden in a subtropical climate—this is their system of layering rose-branches. My idea of layering carnations, shrubs, or any other plants, had always been to cut the plant at a joint, and peg it firmly into the ground, covering with a few inches of fine soil; but the Madeira gardeners adopt a different system, anyway, with regard to their roses. The branch for layering is not chosen near the ground, but often at a height of from two to four feet. The chosen branch is passed through the hole at the bottom of a flower-pot, or a box with a good-sized hole in it answers the same purpose; the pot or box is then supported at the necessary height on a tripod of sticks or bamboos. The branch has an upward slit made in the ordinary way, and the pot is then filled with soil. In two or three months’ time, I was assured, the branch would be well rooted and ready to be transplanted to its fresh quarters. It seemed a simple method of increasing rose-trees, which, as a rule, in climates like those of Madeira, flourish much better when grown on their own roots than grafted on to a foreign stock. The same system appears to answer admirably for the increase of shrubs and even trees, and is extensively adopted for creepers, especially bougainvilleas, which do not strike readily from cuttings; so it is no uncommon sight to see pots lodging among the branches of trees, with a layered branch ready to form a new tree.